Published online Dec 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11392

Peer-review started: July 1, 2021

First decision: July 26, 2021

Revised: July 27, 2021

Accepted: November 14, 2021

Article in press: November 14, 2021

Published online: December 26, 2021

Processing time: 175 Days and 0.7 Hours

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease that mainly affects the spine and sacroiliac joints. To the best of our knowledge, AS with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has rarely been reported. Here, we report an unusual case of AS with AMI in a young patient.

A 37-year-old man was admitted to the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology of our hospital on March 14, 2020, for low back pain. Further evaluation with clinical examinations, laboratory tests, and imaging resulted in a diagnosis of AS. Treatment with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor partially improved his symptoms. However, his back pain persisted. After 6 wk of treatment, he was admitted to the emergency room of another hospital in this city for sudden-onset severe chest pain consistent with a diagnosis of AMI. Angiography revealed severe narrowing of the coronary arteries. Surgical placement of two coronary stents completely relieved his back pain.

AS can cause cardiovascular diseases, including AMI. It is important to consider the cardiovascular risks in the management of AS.

Core Tip: We described a case of a young man with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) who presented with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). In addition to treatment with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, stent placement completely relieved his back pain. This study highlights the possibility for AS to present with cardiovascular manifestations, including life-threatening AMI. Hence, it is important to consider the AS-related cardiovascular risk in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with back pain.

- Citation: Wan ZH, Wang J, Zhao Q. Acute myocardial infarction in a young man with ankylosing spondylitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(36): 11392-11399

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i36/11392.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11392

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease that mainly affects the sacroiliac and axial joints of the spine. In addition to back pain, it may present with constitutional symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, and anemia. AS has also been associated with a myriad of extra-articular manifestations, such as uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease, IgA nephropathy, and psoriasis. However, cardio

A 37-year-old man presented with a 6-mo history of low back pain and a 2-mo history of neck and knee pain.

Six months prior to the consultation, the patient experienced low back pain without obvious causes mainly occurring at night. It was accompanied by morning stiffness and relieved by exercise. Two months ago, he started to experience neck and knee pain with no associated swelling, oral ulcers, and heel pain. Six weeks later, he presented with sudden-onset severe chest pain.

This patient had no history of chronic diseases, such as hypertension, hyperuricemia, hyperlipidemia, and coronary heart disease.

The patient was a non-smoker and had no family history of AS.

He had tenderness in the cervical spine and knees. The finger-to-floor distance was 45 cm; scoliosis distance was greater than 5 cm on both sides; thoracic expansion was 3 cm; occiput-to-wall distance was 0 cm; tragus-to-wall distance was 8 cm; and Schober’s test revealed a 5 cm increase in distance upon lumbar flexion. The four-character test was positive for both lower limbs.

The patient’s ESR and CRP level were 40 mm/h and 36 mg/L, respectively. The test result for HLA-B27 was positive. Rheumatoid factor, anti-keratin antibody, anti-perinuclear factor, and anti-cyclic citrulline acid antibody test results were all negative. Routine blood tests, blood sugar, and blood lipids were unremarkable. Liver and kidney function were normal.

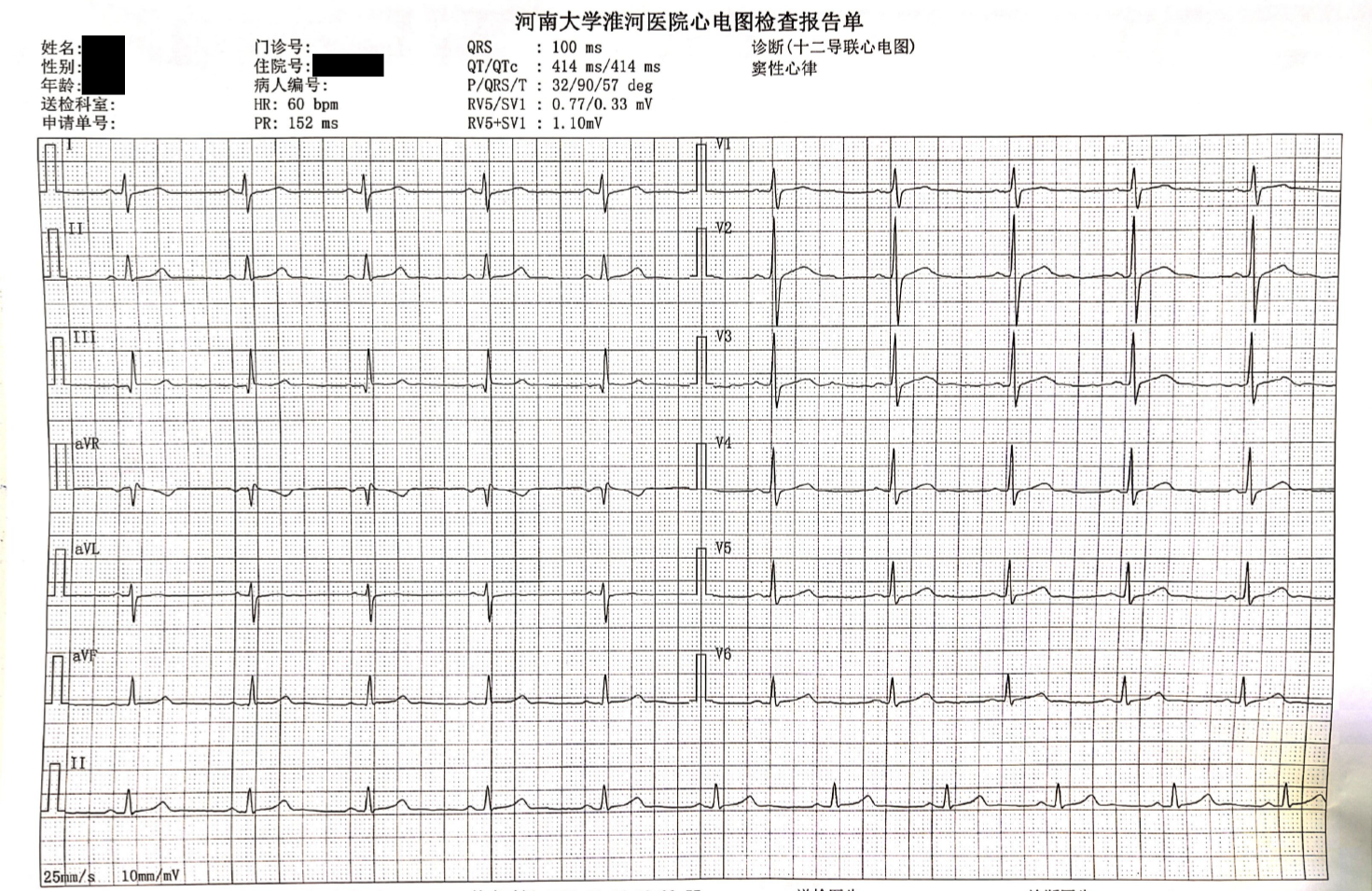

Plain hip and pelvic radiography revealed blurring of the right sacroiliac joint space. computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging of the sacroiliac joint showed findings consistent with right sacroiliac arthritis (grade III). Electrocardiogram (ECG) tracings revealed no abnormalities (Figure 1). Color Doppler cardiac ultrasound and chest CT showed unremarkable findings.

The patient was diagnosed with AS based on the 1984 New York diagnostic criteria for AS.

The patient was administered twice-daily oral doses of celecoxib (NSAID) 0.2 g and thalidomide (disease-modifying antirheumatic drug) 50 mg once a night with a once-weekly dose of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) 50 mg ih. Upon discharge after one week, his neck and knee pain were significantly resolved, although his back pain persisted. He was advised to continue using the prescribed treatment regimen. A follow-up at one month revealed a reduction in ESR and CRP to 25 mm/h and 7 mg/L, respectively. During this time, his neck and knee pain were completely re

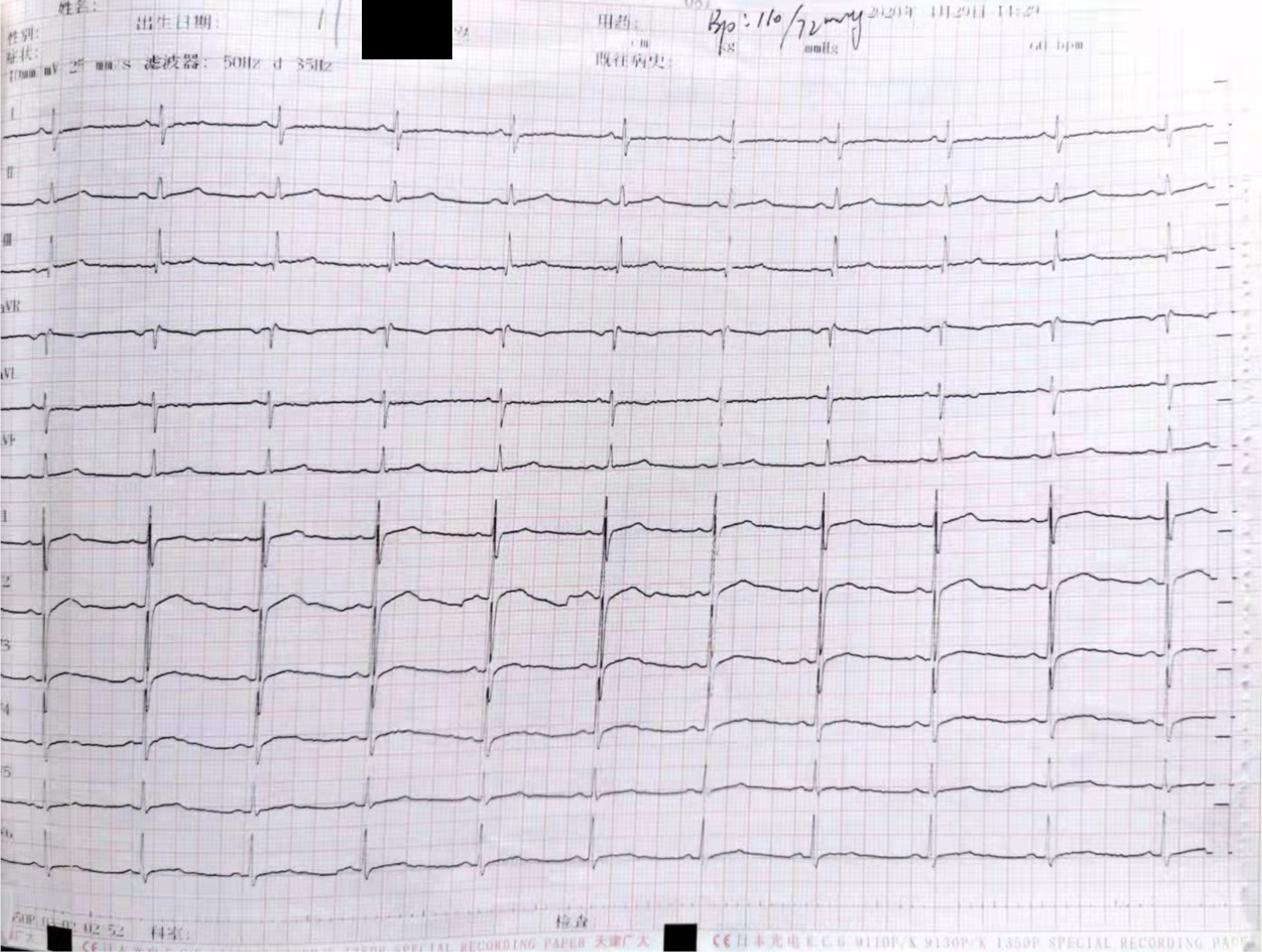

Gastroscopy indicated esophagitis and superficial gastritis with erosion. Treatment with proton pump inhibitor for acid suppression, stomach protection, and gastric motility therapy did not alleviate his symptoms. After six weeks of treatment, the patient suddenly developed severe and persistent chest pain on April 29, 2020, which prompted a consult at the emergency department of another hospital. He was immediately subjected to an emergency laboratory test which results are troponin 11.663 μmol/L, CK279U/L, CK-MB28U/L, ECG (Figure 2): Low T wave on V4-6 limb leads. He was considered as acute non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

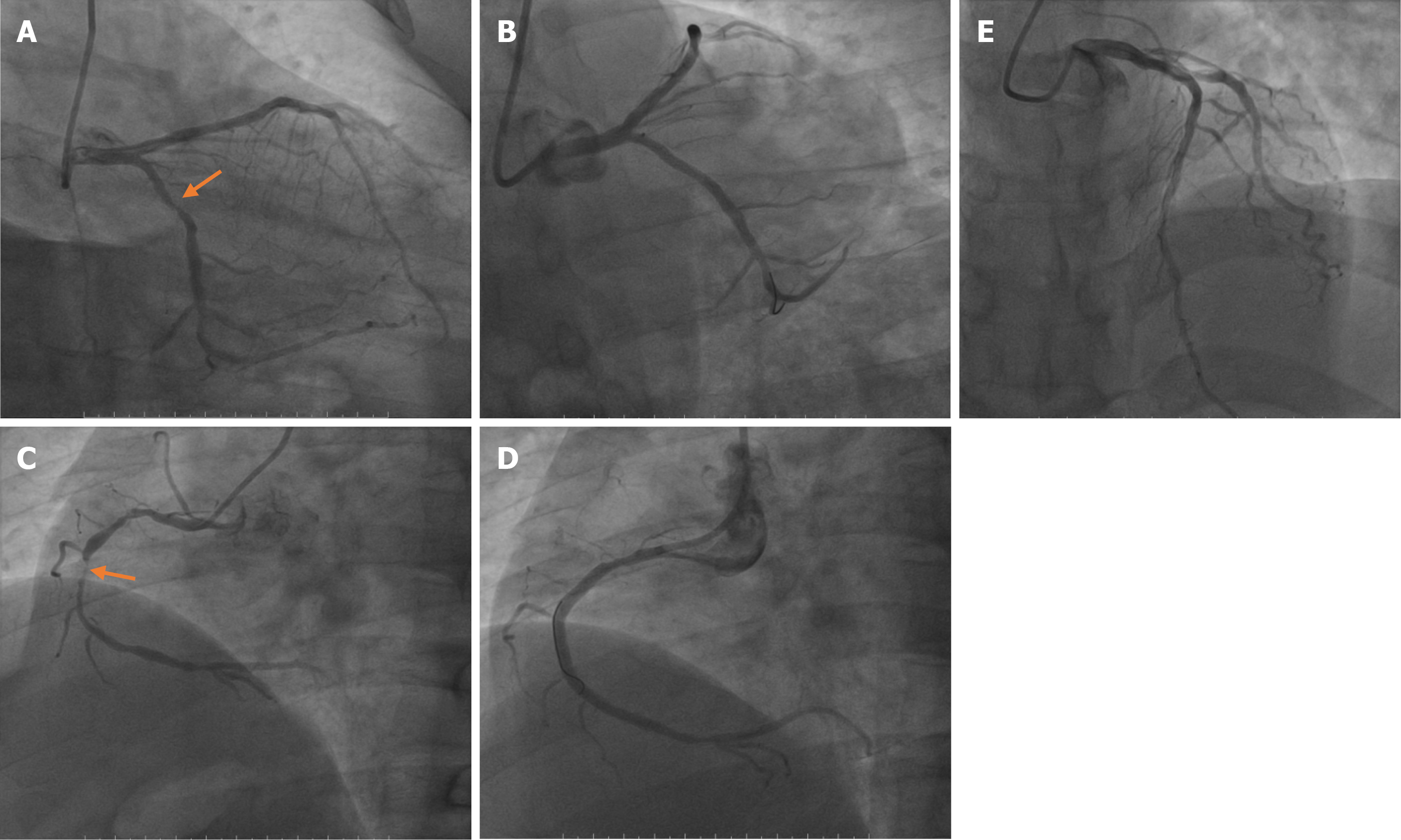

Because of the possibility of AMI, an immediate coronary angiography was performed. Coronary angiography (Figure 3) showed diffuse lesions on the entire right coronary artery (maximal stenosis: 95%), middle segment of the circumflex branch (maximal stenosis: 80%), and entire anterior descending branch (maximal stenosis: 80%). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of AMI based on China’s 2001 diagnostic criteria for AMI. Surgical placement of three coronary stents completely relieved his back pain.

The patient continued to visit our clinic regularly for follow-up visits. There were no recurrences of back pain reported. However, the patient experienced skin rashes after taking thalidomide, likely due to drug allergy. Hence, this drug was discontinued in the regimen. For AS, he is currently taking a TNFi. For his post-AMI state, he was prescribed aspirin, clopidogrel, statins, and other secondary prevention drugs for coronary heart disease. His conditions were considered stable.

We retrieved a few retrospective and prospective studies on AS combined with AMI from PubMed, MESTR, and other databases[1]. Among patients diagnosed with AS, the prevalence of AMI is 0.48%-4.4%. The average age of onset is 46.1 years. There are currently no statistics on sex. In China, there have been no large-scale retrospective or prospective studies. Currently, there are only two reported cases. There were seven male patients in total with an average age of 44-59 years at the time of AMI. Among them, two patients reported by Li Z were twin brothers aged 51 years.

Our case differs from the two domestic reports in that our patient was only 37 years old when he had AMI and he had no known comorbid cardiovascular disease. To the best of our knowledge, our patient was the youngest reported case of AMI with AS in the country.

Generally, patients with AMI presented with chest pain, precordial pain, chest tightness, diaphoresis, and other symptoms of angina a few hours or months before onset. Because angina pectoris is also not common[2], it is more likely to be missed by non-specialist doctors. In our cases, the patient presented with AMI after six weeks of treatment.

To strengthen the understanding of cardiovascular involvement in AS patients, we conducted a literature search in this area. A prospective national cohort study[3] in Sweden revealed that the risk for acute coronary syndrome in patients with AS is 1.99 higher than that of the general population. Another review[4] showed that compared with the general population, the risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) is increased in all types of arthritis, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), gout, and osteoarthritis. Moreover, the study also revealed that the risk for CVD in patients with AS is three times higher than that of the general population[4]. Moreover, there are evidences that patients with chronic inflammatory diseases might have an altered outcome after an CVD event[5,6]. Patients with AS tend to have a higher comorbidity burden for first AMI at admission. The mortality increased after a first AMI during days 31-365 among patients with AS compared with the general population[7]. Therefore, it is particularly important to understand the CVD risk factors in patients with AS. In the management and follow-up of AS patients, screening for CVD-related risk factors could facilitate early interventions to avoid serious CVD events.

Known risk factors for CVD include hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, etc. Patients with AS were more likely to have these risk factors than the general population[8]. A recent study[9] reported that the incidence of AS combined with hyperlipidemia (20.7%) was significantly higher compared to the incidence of hyperlipidemia alone in the general population (16.7%). Moreover, a study[10] found that hypertension was more common in patients with AS than in the control group. It was estimated that for every 5 years of having AS, the incidence of hypertension increases by 1.129 times[11], implying that hypertension may be related to the disease activity. Moreover, this may be due to the underlying inflammation and limited physical activity in patients with AS[12]. The ASAS-COMOSPA study[13] showed that among patients with spondyloarthritis (SpA), such as AS without a history of hypertension, 14.7% had systolic hypertension.

A positive correlation has been shown between age and CVD risk. However, Huang et al[14] found that young patients with newly diagnosed AS had an increased risk of ischemic cardiomyopathy. They compared randomly selected patients with AS (n = 4794), aged 18 to 45 years to sex- and age-matched patients without AS (n = 23970). The results showed that the probability of AMI in the AS group was 1.47 times higher than that in the non-AS group. A 5-year follow-up study[15] in Taiwan found that age was an important factor in the development of CVD in patients with AS such that young male patients dominate in AS. The specific reasons and mechanisms are still unclear. Further studies must be done to elucidate these processes. Nevertheless, it is important to consider the possibility of CVD in young patients with AS. Routine monitoring and evaluation throughout the course of the disease are particularly crucial to prevent life-threatening CVD events.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic progressive inflammatory vascular disease that serves as the pathological basis of CVD. Compared with healthy controls, the incidence of subclinical atherosclerosis in AS patients without CVD was higher[16], which may be related to the endothelial dysfunction associated with AS. A prospective study in Turkey[17] showed that the epicardial adipose tissue thickness (EATT) of the AS group and the control group were 5.74 ± 1.22 mm and 4.91 ± 1.21 mm (P < 0.001), respectively. Furthermore, the pulse velocity (PWV) of the AS group and the control group were 9.90 ± 0.98 m/s and 6.46 ± 0.83 m/s (P = 0.009), respectively. Compared with the control group, patients with AS had significantly higher EATT and PWV. Because EATT and PWV are signs of atherosclerosis and CVD, the measurement of these parameters can be used to identify subclinical atherosclerotic vascular changes in AS patients. Another study found that carotid artery intima-media thickness (cIMT) and flow-mediated dilation (FMD) can be used as markers for subclinical atherosclerosis by measuring arterial stiffness in AS patients[18].

NSAIDs are considered the first-line long-term drug therapy for AS. Although COX-2 selective inhibitors have relatively high gastrointestinal safety, these are not safe for patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases because of the associated risk for thrombotic events. In a prospective study[19] of 628 AS patients without hypertension, 52 patients on continuous NSAIDs presented with hypertension. Continuous NSAIDs use was associated with a 12% increased risk for hypertension compared with non-continuous or no use of NSAIDs[19]. Therefore, for patients with AS who need long-term anti-inflammatory and analgesic therapy, it is important to consider the gastrointestinal and CVD risks in selecting the appropriate NSAIDs for each patient. Nevertheless, some studies suggest that the harmful effects of NSAIDs may be outweighed by the anti-inflammatory benefits in patients with arthritis, such as RA, AS, and PsA[20].

Some scholars think Thalidomide is associated with venous and arterial thrombotic events[21]. The related mechanisms have been explored such as serum levels of the anticoagulant pathway cofactor thrombomodulin transiently dropped during the first month of thalidomide therapy, with gradual recovery over the following two months[22]. Patients with multiple myeloma treated with thalidomide had high levels of von Willebrand factor antigen and of procoagulant factor VIII which were associated with an increased risk of thrombotic events in the general population[23]. However, AMI caused by thalidomide generally has no obvious evidence of atherosclerosis through coronary angiography, which may be related to coronary artery spasm[24]. This patient has obvious evidence of coronary atherosclerosis, so whether it is related to thalidomide is currently uncertain, but the rare cardiovascular events of thalidomide should be considered when choosing DMARDs, and formulate appropriate treatment for the patient Program.

TNF-α plays a key role in the pathogenesis of AS. Botelho[25] reported that TNF-α influences the development of atherosclerosis. Although its exact mechanism remains unclear, TNF-α has been shown to promote atherosclerosis by increasing the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) transendothelial cell endocytosis. TNFi is currently the most widely used biologic drug for the treatment of AS. Studies have reported that TNFi can significantly reduce total cholesterol and LDL, which could delay the process of atherosclerosis and prevent CVDs[26]. A 12-mo follow-up study[27] that determined various markers for atherosclerosis (i.e., FMD, cIMT, and PWV) on 17 patients with AS who were treated with etanercept revealed significant improvements on FMD and PWV (P = 0.065) with no observed thickening on cIMT. Therefore, TNFi can improve and stabilize the vascular pathologies of patients with AS.

We have reported a case of AMI in a relatively young patient with AS. Because of the increased risk for CVD in patients with AS, screening and management for CVD-related risk factors may greatly benefit young patients in preventing life-threatening CVD events.

In summary, the increased risk for CVD in patients with AS is partially due to traditional risk factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and obesity. The underlying chronic systemic inflammation due to AS is the main factor that accelerates the development of atherosclerosis. Although NSAIDs are considered the first-line treatment for AS, long-term NSAIDs use breaks the physiologic barrier against platelet aggregation, causing thrombosis and serious CVD events. Therefore, early identification and intervention of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with SpA are very important. In the 2016 update, the European Union Against Rheumatism recom

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Immunology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cure E S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Park CJ, Choi YJ, Kim JG, Han IB, Do Han K, Choi JM, Sohn S. Association of Acute Myocardial Infarction with ankylosing Spondylitis: A nationwide longitudinal cohort study. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;56:34-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Brophy S, Cooksey R, Atkinson M, Zhou SM, Husain MJ, Macey S, Rahman MA, Siebert S. No increased rate of acute myocardial infarction or stroke among patients with ankylosing spondylitis-a retrospective cohort study using routine data. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:140-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Birnbach B, Höpner J, Mikolajczyk R. Cardiac symptom attribution and knowledge of the symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20:445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mathieu S, Soubrier M. [Cardiovascular risk in ankylosing spondylitis]. Presse Med. 2015;44:907-911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liew JW, Ramiro S, Gensler LS. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32:369-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mantel Ä, Holmqvist M, Jernberg T, Wållberg-Jonsson S, Askling J. Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a more severe presentation of acute coronary syndrome and worse short-term outcome. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3413-3422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Södergren A, Askling J, Bengtsson K, Forsblad-d'Elia H, Jernberg T, Lindström U, Ljung L, Mantel Ä, Jacobsson LTH. Characteristics and outcome of a first acute myocardial infarction in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:1321-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhao SS, Robertson S, Reich T, Harrison NL, Moots RJ, Goodson NJ. Prevalence and impact of comorbidities in axial spondyloarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:iv47-iv57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | García-Gómez C, Martín-Martínez MA, Fernández-Carballido C, Castañeda S, González-Juanatey C, Sanchez-Alonso F, González-Fernández MJ, Sanmartí R, García-Vadillo JA, Fernández-Gutiérrez B, García-Arias M, Manero FJ, Senabre JM, Rueda-Cid A, Ros-Expósito S, Pina-Salvador JM, Erra-Durán A, Möller-Parera I, Llorca J, González-Gay MA; CARMA Project Collaborative Group. Hyperlipoproteinaemia(a) in patients with spondyloarthritis: results of the Cardiovascular in Rheumatology (CARMA) project. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37:774-782. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Bengtsson K, Forsblad-d'Elia H, Lie E, Klingberg E, Dehlin M, Exarchou S, Lindström U, Askling J, Jacobsson LTH. Are ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events? Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Derakhshan MH, Goodson NJ, Packham JC, Sengupta R, Molto A, Marzo-Ortega H, Siebert S; BRITSpA and COMOSPA Investigators. Increased Risk of Hypertension Associated with Spondyloarthritis Disease Duration: Results from the ASAS-COMOSPA Study. J Rheumatol. 2019;46:701-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fotoh DS, Serag DM, Badr IT, Saif DS. Prevalence of Subclinical Carotid Atherosclerosis and Vitamin D Deficiency in Egyptian Ankylosing Spondylitis Patients. Arch Rheumatol. 2020;35:335-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Moltó A, Etcheto A, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, van den Bosch F, Bautista Molano W, Burgos-Vargas R, Cheung PP, Collantes-Estevez E, Deodhar A, El-Zorkany B, Erdes S, Gu J, Hajjaj-Hassouni N, Kiltz U, Kim TH, Kishimoto M, Luo SF, Machado PM, Maksymowych WP, Maldonado-Cocco J, Marzo-Ortega H, Montecucco CM, Ozgoçmen S, van Gaalen F, Dougados M. Prevalence of comorbidities and evaluation of their screening in spondyloarthritis: results of the international cross-sectional ASAS-COMOSPA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1016-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang YP, Wang YH, Pan SL. Increased risk of ischemic heart disease in young patients with newly diagnosed ankylosing spondylitis--a population-based longitudinal follow-up study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hung YM, Chang WP, Wei JC, Chou P, Wang PY. Midlife Ankylosing Spondylitis Increases the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases in Males 5 Years Later: A National Population-Based Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sarp Ü, ÜstÜner E, Kutlay S, Ataman Ş. Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients With Ankylosing Spondylitis. Arch Rheumatol. 2020;35:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Demir K, Avcı A, Ergulu Esmen S, Tuncez A, Yalcın MU, Yılmaz A, Yılmaz S, Altunkeser BB. Assessment of arterial stiffness and epicardial adipose tissue thickness in predicting the subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2021;43:169-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bai R, Zhang Y, Liu W, Ma C, Chen X, Yang J, Sun D. The Relationship of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Subclinical Atherosclerosis: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Angiology. 2019;70:492-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liew JW, Ward MM, Reveille JD, Weisman M, Brown MA, Lee M, Rahbar M, Heckbert SR, Gensler LS. Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drug Use and Association With Incident Hypertension in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72:1645-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Castañeda S, Vicente-Rabaneda EF, García-Castañeda N, Prieto-Peña D, Dessein PH, González-Gay MA. Unmet needs in the management of cardiovascular risk in inflammatory joint diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:23-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang S, Yang J, Jin X, Zhang S. Myocardial infarction, symptomatic third degree atrioventricular block and pulmonary embolism caused by thalidomide: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Corso A, Lorenzi A, Terulla V, Airò F, Varettoni M, Mangiacavalli S, Zappasodi P, Rusconi C, Lazzarino M. Modification of thrombomodulin plasma levels in refractory myeloma patients during treatment with thalidomide and dexamethasone. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:588-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Minnema MC, Fijnheer R, De Groot PG, Lokhorst HM. Extremely high levels of von Willebrand factor antigen and of procoagulant factor VIII found in multiple myeloma patients are associated with activity status but not with thalidomide treatment. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:445-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kardasz I, De Caterina R. Myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries: a conundrum with multiple aetiologies and variable prognosis: an update. J Intern Med. 2007;261:330-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Atzeni F, Nucera V, Galloway J, Zoltán S, Nurmohamed M. Cardiovascular risk in ankylosing spondylitis and the effect of anti-TNF drugs: a narrative review. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020;20:517-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Botelho KP, Pontes MAA, Rodrigues CEM, Freitas MVC. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome Among Patients with Psoriasis Treated with TNF Inhibitors and the Effects of Anti-TNF Therapy on Their Lipid Profile: A Prospective Cohort Study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2020;18:154-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Végh E, Kerekes G, Pusztai A, Hamar A, Szamosi S, Váncsa A, Bodoki L, Pogácsás L, Balázs F, Hodosi K, Domján A, Szántó S, Nagy Z, Szekanecz Z, Szűcs G. Effects of 1-year anti-TNF-α therapy on vascular function in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:427-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, Heslinga M, McInnes IB, Peters MJ, Kvien TK, Dougados M, Radner H, Atzeni F, Primdahl J, Södergren A, Wallberg Jonsson S, van Rompay J, Zabalan C, Pedersen TR, Jacobsson L, de Vlam K, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Semb AG, Kitas GD, Smulders YM, Szekanecz Z, Sattar N, Symmons DP, Nurmohamed MT. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:17-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 957] [Cited by in RCA: 864] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |