Published online Dec 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11338

Peer-review started: April 17, 2021

First decision: July 15, 2021

Revised: August 6, 2021

Accepted: November 5, 2021

Article in press: November 5, 2021

Published online: December 26, 2021

Processing time: 250 Days and 6.5 Hours

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients who suffer severe infection or comorbidities have an increased risk of developing fungal infections. There is a possibility that such infections are missed or misdiagnosed, in which case patients may suffer higher morbidity and mortality. COVID-19 infection, aggressive management strategies and comorbidities like diabetes render patients prone to opportunistic fungal infections. Mucormycosis is one of the opportunistic fungal infections that may affect treated COVID patients.

We present a case series of four adult males who were diagnosed with mucormycosis post-COVID-19 recovery. All the patients had diabetes and a history of systemic corticosteroids for treatment of COVID-19. The mean duration between diagnosis of COVID-19 and development of symptoms of mucor was 15.5 ± 14.5 (7–30) d. All patients underwent debridement and were started on antifungal therapy. One patient was referred to a higher center for further management, but the others responded well to treatment and showed signs of improvement at the last follow-up.

Early diagnosis and management of mucormycosis with appropriate and aggressive antifungals and surgical debridement can improve survival.

Core Tip: Mucormycosis usually indicates a serious underlying medical condition such as diabetes. Furthermore, the immune dysregulation post coronavirus disease 2019, and widespread use of immunosuppressants and broad-spectrum antibiotics may lead to enhanced susceptibility to a number of secondary opportunistic infections such as mucormycosis. Clinical suspicion along with prompt microbiological diagnosis are indispensable to a positive case outcome.

- Citation: Upadhyay S, Bharara T, Khandait M, Chawdhry A, Sharma BB. Mucormycosis – resurgence of a deadly opportunist during COVID-19 pandemic: Four case reports. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(36): 11338-11345

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i36/11338.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11338

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) is known to infect alveolar epithelial cells (pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome) as well as monocytes/macrophages leading to a cytokine storm (multiorgan failure and death)[1]. The cytokine storm seen in severe cases has led to increased use of steroids and other immunosuppressive therapy in moderate-to-severe cases. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, aggressive management strategies and como

Mucormycosis is a deadly and rapidly progressive fungal infection of humans. The usual presentation is rhinocerebral mucormycosis[4]. Oral mucormycosis is an unusual manifestation of the disease mainly affecting immunocompromised patients such as those with DM, corticosteroid treatment, leukemia, lymphoma, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection etc.[3,5,6]. Although there are few publications on fungal co-infections associated with COVID-19, it is pertinent to point out that there is a high chance of missed or misdiagnosis in these cases.

To analyze mucor infections in COVID-19 patients, we searched PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science, using the keywords ‘‘mucor’’, ‘‘mucormycosis’’, ‘‘opportunistic fungal infection’’, ‘‘oral fungal infections’’, ‘‘post COVID infection’’, ‘‘COVID-19’’ or ‘‘SARS-CoV-2’’ (up to April 16, 2021). Through this report, we provide an insight into clinical features, laboratory diagnosis and significance of timely management of post-COVID mucormycosis infection through a series of four cases who presented to the outpatient department of our hospital.

All the cases presented to the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery with chief complaints of pain, swelling and pus discharge from their oral cavity.

Case 1: A 39-year-old man presented to the outpatient department (OPD) complaining of pain and mobility in the teeth of the upper jaw region for the past 2 mo. The patient gave a history of extraction of a tooth in the upper jaw 2 mo previously, after which he developed a nonhealing painful lesion. The pain gradually spread to the entire left maxilla (Figure 1A).

Case 2: A 57-year-old man presented to the OPD with gingival swelling and multiple draining sinuses on right and left anterior maxilla and right side of the palate for the past 1 wk (Figure 1B). The patient presented to the OPD with the same complaints 1 wk previously and was prescribed antibiotics, however, he did not obtain any relief.

Case 3: A 45-year-old man presented to the OPD with chief complaints of pain, bleeding and ulcers in the gums.

Case 4: A 55-year-old man presented to the OPD with chief complaints of pus discharge and bleeding from the gums (Figure 1C).

All four patients had a history of uncontrolled DM. All the cases gave a past history of suffering from COVID-19 that dated back 2–3 mo. Case 1 suffered from COVID-19 3 mo back. Case 2 was hospitalized for 17 d for treatment of COVID-19. He developed the mucosal lesions 9 d after recovery from COVID-19. Case 3 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 3 mo back, and he recovered from the viral infection after 15 d of treatment. He noticed the presenting lesions 1 wk after recovery from COVID-19 infection. Case 4 was apparently well 2 mo back when he tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 through RT-PCR. He recovered from the viral infection after 10 d of treatment. The patient developed the present lesions 16 d after recovery from COVID-19.

All the patients were afebrile at presentation. In Case 1, both maxilla showed the presence of pus-discharging sinuses. The patient’s mouth opening was found to be adequate. Case 2 showed gingival swelling and multiple draining sinuses on both anterior maxilla and also the right side of the palate. Case 3 demonstrated gingival swelling and multiple draining sinuses on both anterior maxilla and the right side of the palate. However, his mouth opening was inadequate. Case 4 had multiple sinus formation on gingiva and discoloration of the hard palate was observed (Figure 1C). On palpation, a maxillary fragment was mobile.

Blood chemistry, arterial blood gas analysis, urinalysis, electrocardiography and chest X-ray were normal in all four cases.

Further diagnostic work-up: All four cases tested negative for HIV antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, and hepatitis virus antibody. Complete blood count, liver function test and kidney function test were within normal ranges.

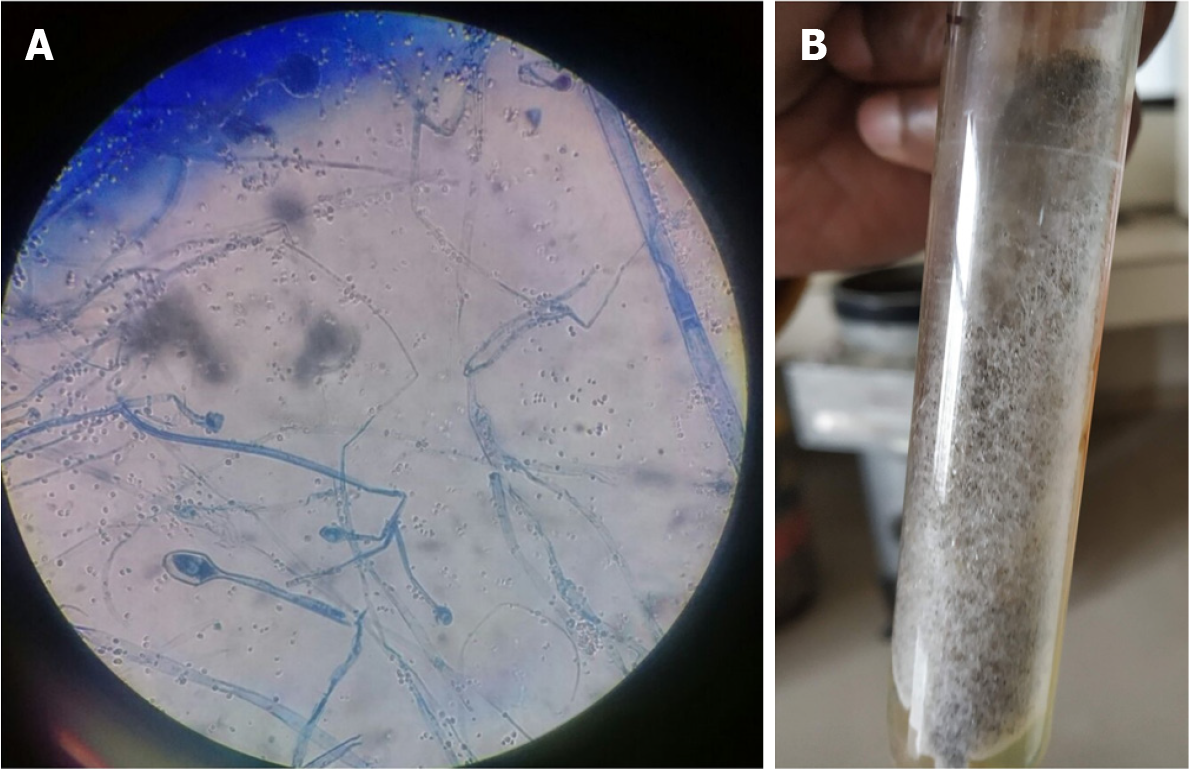

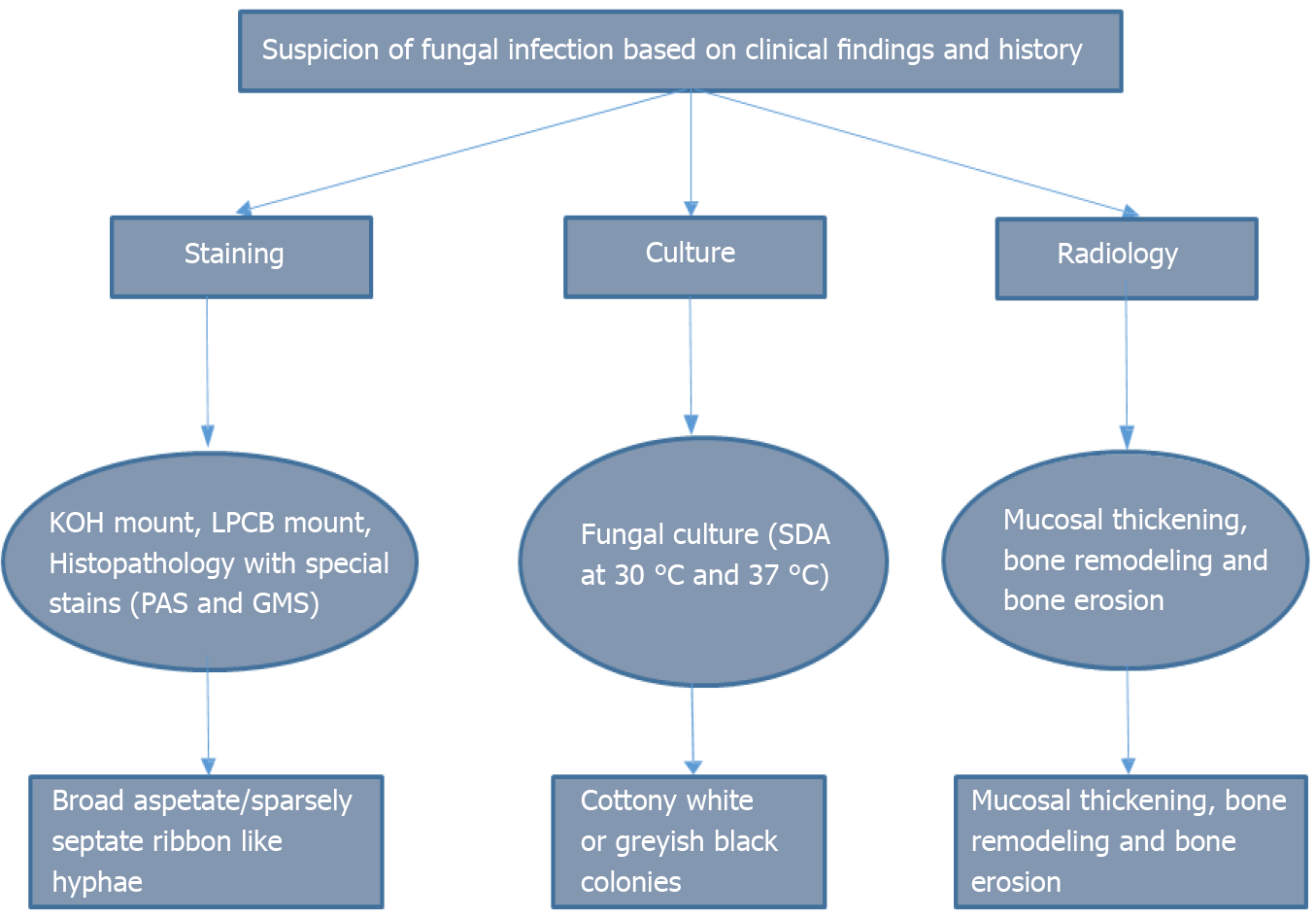

Microbiological identification of the causative agent: The tissues/pus samples from the lesions were analyzed by direct microscopy and culture (Figure 2). The potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount of direct specimens showed broad aseptate hyaline hyphae. The tissue specimens from maxillary sinuses of all the cases showed granulomatous reaction with thick, broad fungal hyphae suggestive of Mucor spp. The specimens were cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) and culture tubes were incubated at 37 ºC and 25 ºC. After 5–10 d of incubation, there was cottony white growth on SDA. Lactophenol cotton blue (LPCB) staining showed broad aseptate hyphae in all four cases.

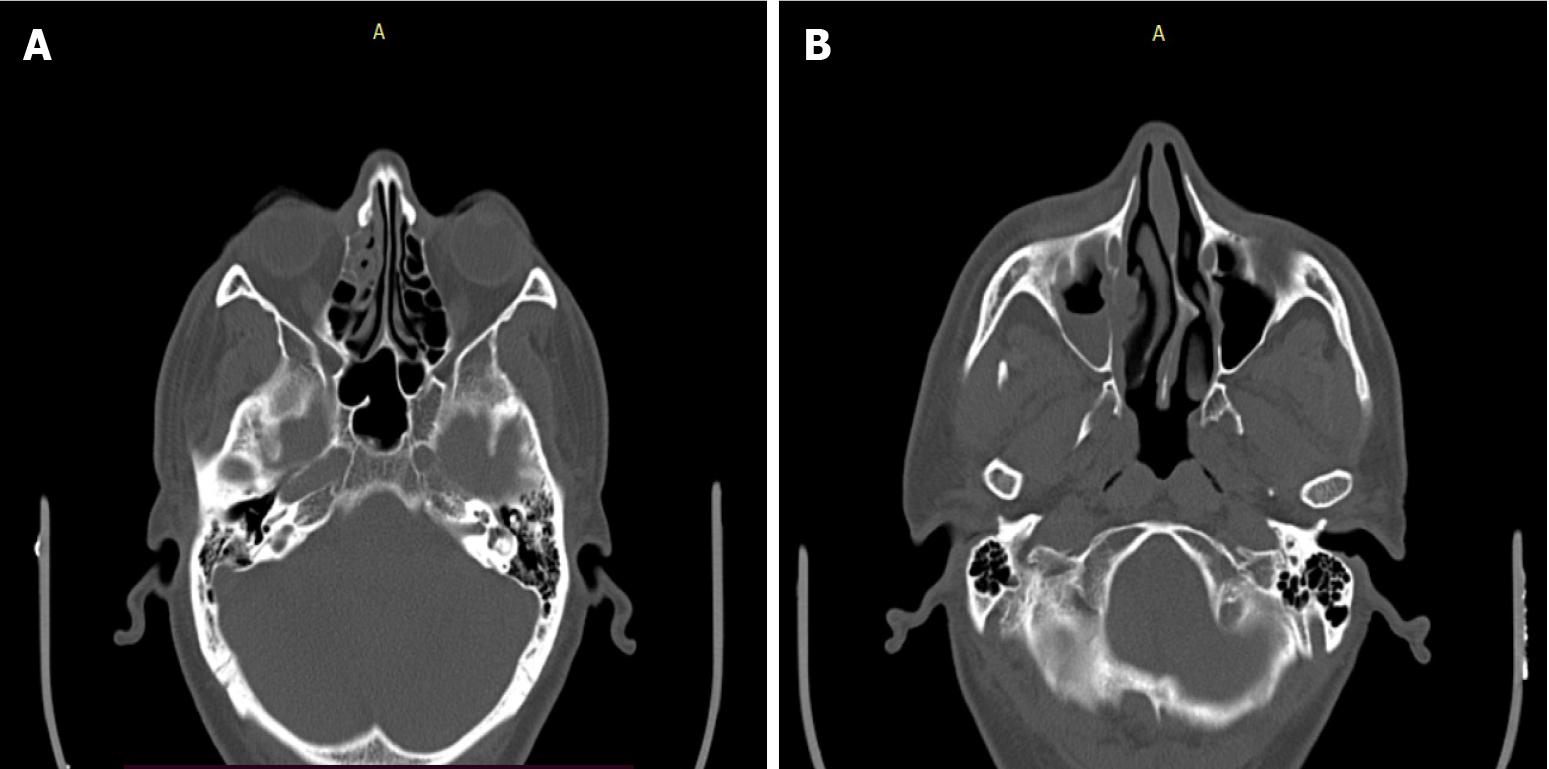

Case 1: Noncontrast computed tomography (NCCT) of paranasal sinuses (PNSs) showed bony defects involving the left side of the alveolar process of the maxilla, and the anterior medial and lateral walls of the left maxillary sinus showed thinning and attenuation/erosion. Findings revealed residual/recurrent fungal sinusitis.

Case 2: NCCT of the PNSs showed bony septa in the right frontal sinus with mucosal thickening and air locules (Figure 3). The right osteomeatal complex was obliterated with adjacent bone erosion and erosion of the medial wall of the right maxillary sinus.

Case 3: Imaging could not be performed as he was referred to a higher center before the investigation could be performed.

Case 4: NCCT of the PNSs showed bony erosion involving both sides of the alveolar process of the maxilla.

Case 1: Surgical debridement of the left maxilla, bullectomy and left ethmoidectomy was performed under general anesthesia.

Case 2: The patient was started on amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (500/125 mg 12 h) and liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg in 10% dextrose).

Case 3: The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin-B (5 mg/kg in 10% dextrose). Since the patient needed extensive surgery, he was referred to a higher center for further management.

Case 4: The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg in 10% dextrose).

The microbiological analysis of pus and tissue specimens showed fungal hyphae in KOH mount. The growth on SDA and LPCB appearance was suggestive of Mucor spp.

Mucormycosis should be treated with liposomal amphotericin B.

NCCT of PNSs was suggestive of structural changes due to mucormycosis.

The final diagnosis of the four cases was post-COVID oral mucormycosis.

All the patients were started on intravenous infusion of liposomal amphotericin B at an initial dose of 5 mg/kg diluted in 10% dextrose. Cases 1 and 3 needed additional surgical intervention. The cases were followed up for clinical and radiological resolution of active disease.

Cases 1, 2 and 4 responded well to treatment. Case 3 could not be followed up as he was referred to a higher center.

We report a series of four cases of oral mucormycosis among male patients with DM. Mucormycosis sometimes appears as a diabetes-defining illness and remains one of the most devastating complications in uncontrolled DM. India contributes to 40% of the global burden of this deadly opportunistic infection, with an estimated prevalence of > 100 cases per million population[4]. All patients in this study had DM and similar oral lesions, and were diagnosed with the help of laboratory tests and NCCT. Two of the patients needed surgical debridement and all four were treated with liposomal amphotericin B. The patients showed improvement in their lesions. One of the patients who had extensive lesions was referred to a higher center for further care.

Huang et al[7] reported a case of oral mucormycosis and extensive maxillary osteonecrosis secondary to dental extraction in a 40-year-old immunocompromised patient. The author emphasized early recognition and aggressive treatment of such patients in order to prevent morbidity and mortality[8]. Fogarty et al[9] and Kumar et al[10] also reported development of oral mucormycosis among elderly immunocompromised men. Various cases of oral mucormycosis reported so far are summarized in Table 1[11-17].

| Ref. | Country | Age (yr)/sex | Site | Comorbidities | Outcome |

| Mehta et al[11] | India | 60/Male | Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis | Uncontrolled diabetes | Death |

| Werthman et al[12] | United States | 33/Female | Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis | Diabetes, asthma, hypertension | Death |

| Hanley et al[13] | United Kingdom | 22/Male | Disseminated (involving the hilar lymph nodes, heart, brain, and kidney)/NA | Pancreatitis | Death |

| Placik et al[14] | Arizona | 49/ Male | Pulmonary mucormycosis | None | Death |

| Monte et al[15] | Brazil | 86/Male | Gastrointestinal mucormycosis | Hypertension | Death |

| Mekonnen et al[16] | United States | 60/Male | Rhino-orbital mucormycosis | Diabetes, asthma, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia | Death |

| Pasero et al[17] | Italy | 66/Male | Sinopulmonary mucormycosis | Lymphopenia, Hypertension | Death |

| This case | India | 4 males, 49 ± 10 (39–57) | Oral mucormycosis | Diabetes mellitus | 3 alive, one lost to follow up |

Another peculiar finding observed in our study was that all the patients gave a past history of COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 is capable of infecting not only intraepithelial cells within the lungs, but also causes an abortive infection of the macrophages and dendritic cells. This leads to a storm of proinflammatory cytokines that renders the patient prone to opportunistic infections such as mucormycosis[1]. Invasive mucormycosis has not only been reported in severe cases but even in mild-to-moderate COVID. Although a few cases of oral mucormycosis have been reported in the literature, this is one of the first case series reported among COVID-19 patients.

Mucormycosis suggests the presence of a pre-existing immunosuppressive condition such as diabetes, leukemia, lymphoma, renal failure, immunosuppressive therapy, malnutrition, viral infection and severe burns. Hyperglycemia due to uncontrolled diabetes is the strongest risk factor for development of mucormycosis. It leads to polymorphonuclear dysfunction, defective chemotaxis and dysregulated intracellular killing. In ketoacidosis, free iron becomes readily available in the serum, which is efficiently taken up by Mucor for its growth and virulence. The association between DM and COVID is a known fact[18]. Corticosteroid use in severe COVID-19 patients with diabetes further impairs the functioning of neutrophils, thus making these patients highly susceptible to development of mucormycosis[3,5,17,18].

Inhalation of fungal spores or direct wound contamination are the two most common causes of oral mucormycosis[19,20]. The most common form of this disease is maxillofacial. Early symptoms of this disease include facial cellulitis, periorbital edema and nasal inflammation, followed by widespread tissue necrosis[21]. Failure of prompt medical and surgical intervention may lead to cerebral spread, cavernous sinus thrombosis, septicemia and multiple organ failure, resulting in high morbidity and mortality[22].

Suspicion of mucormycosis is based on laboratory and imaging findings, risk factors and disease progression while on any antibacterial or antifungal therapy that does not cover Mucor infection. The pathognomonic feature of mucormycosis is tissue necrosis manifesting as a necrotic lesion, eschar or black discharge in the nasal or oral cavity[23].

Rapid diagnostic methods include biopsy, KOH mount and Calcofluor stain. Since it is difficult to routinely culture Mucor, biopsy is preferred for confirmation of diagnosis[2,21,23] (Figure 4). Management includes antifungal therapy, surgical debridement, diagnosis and treatment of the underlying predisposing factors, and adjuvant therapy. Amphotericin B is the standard treatment for invasive mucormycosis[24]. Pos

Clinical suspicion, meticulous diagnosis, coordination between different medical departments and timely intervention were the strengths of our study. Limitation of the study were that antifungal susceptibility testing and further molecular characterization of the isolated fungal pathogen could not be done due to limitation of resources.

Clinicians should be familiar with presentations of rare opportunistic fungal infections and keep a high index of suspicion in post-COVID patients with DM. A multidisciplinary approach facilitating early diagnosis, aggressive surgical intervention, medical treatment with amphotericin B and controlling DM are the mainstay for improving the outcome of patients with mucormycosis in post-COVID patients. The incidence of oral mucormycosis may increase, either as co-infection or as a sequela of COVID-19. Therefore, urgent reporting of any new information is of importance to keep the scientific community abreast with what all can go wrong post-COVID infection, which till now is unexplored territory.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bhatt KP S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Chakravarti A, Upadhyay S, Bharara T, Broor S. Current understanding, knowledge gaps and a perspective on the future of COVID-19 Infections: A systematic review. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2020;38:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Song G, Liang G, Liu W. Fungal Co-infections Associated with Global COVID-19 Pandemic: A Clinical and Diagnostic Perspective from China. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:599-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Corzo-León DE, Chora-Hernández LD, Rodríguez-Zulueta AP, Walsh TJ. Diabetes mellitus as the major risk factor for mucormycosis in Mexico: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and outcomes of reported cases. Med Mycol. 2018;56:29-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Prakash H, Chakrabarti A. Global Epidemiology of Mucormycosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2019;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 79.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moorthy A, Gaikwad R, Krishna S, Hegde R, Tripathi KK, Kale PG, Rao PS, Haldipur D, Bonanthaya K. SARS-CoV-2, Uncontrolled Diabetes and Corticosteroids-An Unholy Trinity in Invasive Fungal Infections of the Maxillofacial Region? J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2021;1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ahmadikia K, Hashemi SJ, Khodavaisy S, Getso MI, Alijani N, Badali H, Mirhendi H, Salehi M, Tabari A, Mohammadi Ardehali M, Kord M, Roilides E, Rezaie S. The double-edged sword of systemic corticosteroid therapy in viral pneumonia: A case report and comparative review of influenza-associated mucormycosis versus COVID-19 associated mucormycosis. Mycoses. 2021;64:798-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huang JS, Kok SH, Lee JJ, Hsu WY, Chiang CP, Kuo YS. Extensive maxillary sequestration resulting from mucormycosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:532-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sen M, Lahane S, Lahane TP, Parekh R, Honavar SG. Mucor in a Viral Land: A Tale of Two Pathogens. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:244-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fogarty C, Regennitter F, Viozzi CF. Invasive fungal infection of the maxilla following dental extractions in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72:149-152. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kumar JA, Babu P, Prabu K, Kumar P. Mucormycosis in maxilla: Rehabilitation of facial defects using interim removable prostheses: A clinical case report. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2013;5:S163-S165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kalaskar RR, Kalaskar AR, Ganvir S. Oral mucormycosis in an 18-month-old child: a rare case report with a literature review. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;42:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mehta S, Pandey A. Rhino-Orbital Mucormycosis Associated With COVID-19. Cureus. 2020;12:e10726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Werthman-Ehrenreich A. Mucormycosis with orbital compartment syndrome in a patient with COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;42:264.e5-264.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hanley B, Naresh KN, Roufosse C, Nicholson AG, Weir J, Cooke GS, Thursz M, Manousou P, Corbett R, Goldin R, Al-Sarraj S, Abdolrasouli A, Swann OC, Baillon L, Penn R, Barclay WS, Viola P, Osborn M. Histopathological findings and viral tropism in UK patients with severe fatal COVID-19: a post-mortem study. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e245-e253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 79.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Placik DA, Taylor WL, Wnuk NM. Bronchopleural fistula development in the setting of novel therapies for acute respiratory distress syndrome in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15:2378-2381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Monte Junior ESD, Santos MELD, Ribeiro IB, Luz GO, Baba ER, Hirsch BS, Funari MP, de Moura EGH. Rare and Fatal Gastrointestinal Mucormycosis (Zygomycosis) in a COVID-19 Patient: A Case Report. Clin Endosc. 2020;53:746-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mekonnen ZK, Ashraf DC, Jankowski T, Grob SR, Vagefi MR, Kersten RC, Simko JP, Winn BJ. Acute Invasive Rhino-Orbital Mucormycosis in a Patient With COVID-19-Associated Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37:e40-e80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pasero D, Sanna S, Liperi C, Piredda D, Branca GP, Casadio L, Simeo R, Buselli A, Rizzo D, Bussu F, Rubino S, Terragni P. A challenging complication following SARS-CoV-2 infection: a case of pulmonary mucormycosis. Infection. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lim S, Bae JH, Kwon HS, Nauck MA. COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: from pathophysiology to clinical management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17:11-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 671] [Cited by in RCA: 583] [Article Influence: 145.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Garg D, Muthu V, Sehgal IS, Ramachandran R, Kaur H, Bhalla A, Puri GD, Chakrabarti A, Agarwal R. Coronavirus Disease (Covid-19) Associated Mucormycosis (CAM): Case Report and Systematic Review of Literature. Mycopathologia. 2021;186:289-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 81.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Corchuelo J, Ulloa FC. Oral manifestations in a patient with a history of asymptomatic COVID-19: Case report. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:154-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Venkatesh D, Dandagi S, Chandrappa PR, Hema KN. Mucormycosis in immunocompetent patient resulting in extensive maxillary sequestration. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2018;22:S112-S116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nilesh K, Vande AV. Mucormycosis of maxilla following tooth extraction in immunocompetent patients: Reports and review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2018;10:e300-e305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Walsh TJ, Skiada A, Cornely OA, Roilides E, Ibrahim A, Zaoutis T, Groll A, Lortholary O, Kontoyiannis DP, Petrikkos G. Development of new strategies for early diagnosis of mucormycosis from bench to bedside. Mycoses. 2014;57 Suppl 3:2-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Fungal diseases, Treatment for Mucormycosis. [cited 16 April 2021] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/mucormycosis/treatment.html#:~:text=Mucormycosis%20is%20a%20serious%20infection,mouth%20(posaconazole%2C%20isavuconazole). |

| 26. | ASA and APSF Joint Statement on Elective Surgery and Anesthesia for Patients after COVID-19 Infection. [cited 15 April 2021] Available from: https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2020/12/asa-and-apsf-joint-statement-on-elective-surgery-and-anesthesia-for-patients-after-covid-19-infection. |