Published online Dec 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10738

Peer-review started: August 15, 2021

First decision: September 2, 2021

Revised: September 14, 2021

Accepted: October 11, 2021

Article in press: October 11, 2021

Published online: December 6, 2021

Processing time: 106 Days and 23.3 Hours

Keratinized gingival insufficiency is a disease attributed to long-term tooth loss, can severely jeopardizes the long-term health of implants. A simple and effective augmentation surgery method should be urgently developed.

A healthy female patient, 45-year-old, requested implant restoration of the her left mandibular first molar and second molar. Before considering a stage II, as suggested from the probing depth measurements, the widths of the mesial, medial, and distal buccal keratinized gingiva of second molar (tooth #37) were measured and found to be 0.5 mm, 0.5 mm, and 0 mm, respectively. This suggested that the gingiva was insufficient to resist damage from bacterial and mechanical stimulation. Accordingly, modified apically repositioned flap (ARF) surgery combined with xenogeneic collagen matrix (XCM) and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) was employed to increase the width of gingival tissue. After 1 mo of healing, the widths of mesial, medial, and distal buccal keratinized gingiva reached 4 mm, 4 mm, and 3 mm, respectively, and the thickness of the augmented mucosa was 4.5 mm. Subsequently, through the second-stage operation, the patient obtained an ideal soft tissue shape around the implant.

For cases with keratinized gingiva widths around implants less than 2mm,the soft tissue width and thickness could be increased by modified ARF surgery combined with XCM and PRF. Moreover, this surgery significantly alleviated patients’ pain and ameliorated oral functional comfort.

Core Tip: The advantages of keratinized gingiva augmentation with xenogeneic collagen matrix and platelet-rich fibrin included: (1) Promotion of soft tissue regeneration; (2) Low risks of infection and pain; (3) Minimally invasive procedure; and (4) Simplified surgical process.

- Citation: Han CY, Wang DZ, Bai JF, Zhao LL, Song WZ. Peri-implant keratinized gingiva augmentation using xenogeneic collagen matrix and platelet-rich fibrin: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(34): 10738-10745

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i34/10738.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10738

Healthy periodontal tissue is an essential precondition for the long-term success of dental implants and can defend against mechanical stimulation and bacterial growth. However, gingiva recession is correlated with loss of teeth and bone, especially in female patients with thin gingiva biotypes that tend towards keratinized gingiva deficiency[1], so it brings risks and difficulty for follow-up restoration. Increasing evidence suggests that the health of the soft tissues surrounding osseointegrated dental implants may substantially influence long-term clinical stability and esthetics[2]. For soft tissue augmentation, free gingiva graft (FGG) surgery is a currently used and effective method that can significantly increase the width and thickness of keratinized gingiva and maintain long-term stability. However, there are some defects (e.g., pain, excessive bleeding, infection, injury to nerves and vessels), so patients are reluctant to undergo the surgery plan[3]. Thus, researchers and doctors are devoted to seeking an alternative method that alleviates side effects while obtaining satisfactory outcomes. After being developed, xenogeneic collagen matrix (XCM) has been widely used in clinical dentistry. The original intention of the XCM membrane was to act as a protective barrier and guide media in guide tissue regeneration surgery, and XCMs have gradually come to play an important role in soft tissue augmentation. Compared with autogenous transplantation, the application of XCM greatly decreased chair-side time, and the regenerated area exhibited a similar appearance to the surrounding natural soft tissue in texture and color[4]. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) could accelerated wound healing because of abundant growth factors. The research confirmed that the combination of PRF and FGG could help in the healing process during soft tissue procedures[5]. Accordingly, a novel method was developed in this study to increase peri-implant keratinized gingiva with a modified apically repositioned flap (ARF) combined with XCM and PRF.

A 43-year-old female patient requested implant restoration of the left mandibular first molar and second molar (teeth #36 and #37).

The two implants of teeth #36 and #37 underwent osseointegration for three months. Before stage II surgery, the widths of the mesial, medial, and distal buccal keratinized gingiva of the second molar (tooth #37) were 0.5 mm, 0.5 mm, and 0 mm, respectively (Figure 1B and C), as revealed by clinical observation.

During the medical history review, the patient denied having systematic diseases and a history of smoking.

The patient denied having personal and family history.

Before stage II surgery, the widths of the mesial, medial, and distal buccal keratinized gingiva of the second molar (tooth #37) were 0.5 mm, 0.5 mm, and 0 mm, respectively (Figure 1B and C), as revealed by clinical observation.

No abnormality found in laboratory examination

Cone beam computed tomography showed good osseointegration around the implant, which suggested that the implant placement was successful (shown in Figure 1A).

Buccal keratinized gingiva insufficiency of tooth #37.

To avoid inflammation, we planned to perform stage II surgery after obtaining sufficient keratinized gingiva. There were two surgical plans for the patient to choose, ARF + FGG surgery, and ARF + XCM + PRF surgery. The patient was informed of the procedure and risks, and she preferred the second method as she was afraid of pain and infection, and written informed consent for surgery was obtained.

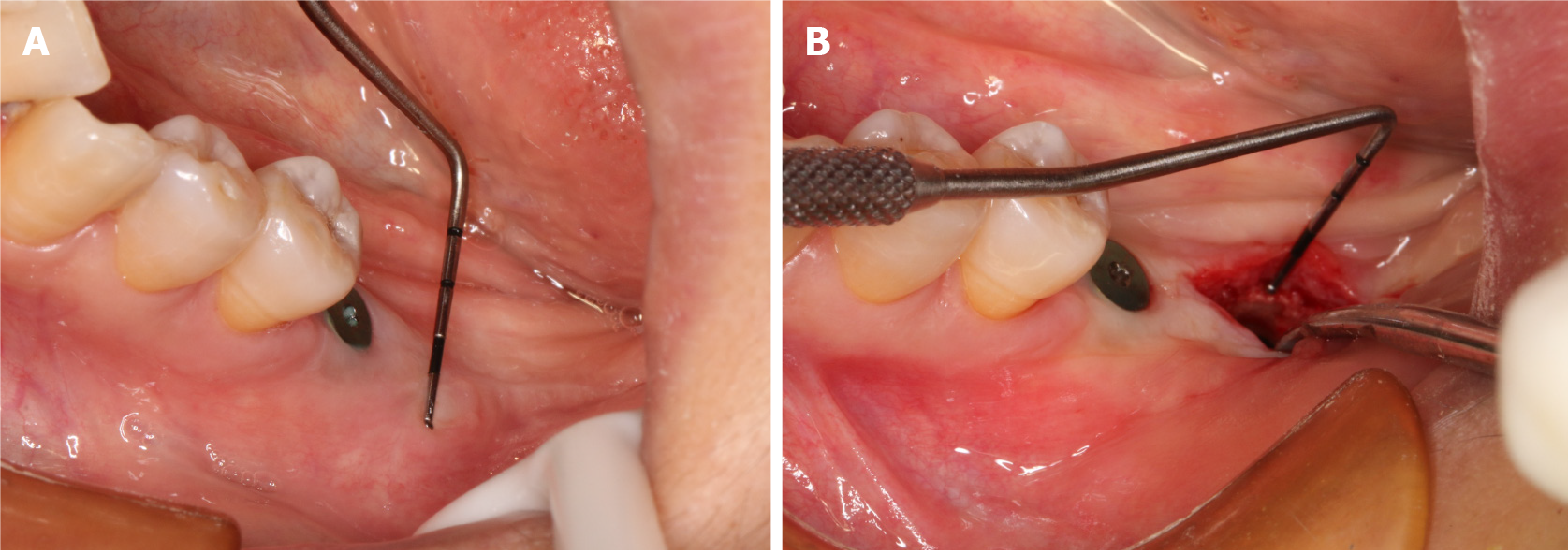

Therefore, an ARF technique correlated with XCM and PRF was performed to increase the reduced keratinized tissue width and thickness, while patient morbidity was reduced by avoiding a second site. Before the surgery, the operative risk and complications were communicated with the patient, and the informed written consent was obtained from the patient for the operation and publishing of the case report. Next, the patient rinsed with mouth 0.12% chlorhexidine for three times. After local infiltration anesthesia by using articacine, a linear incision that deviated lingually was made, as showed Figure 2A. As it was impacted by buccal muco-gingival movement, the buccal full-thickness flap was split into a semi-thick flap with a No. 15 blade (Figure 2B), and the upper flap was positioned apically with 5-0 protein absorbable sutures by a vertical mattress (Figure 2C and D). The graft procedure involved the following two steps. First, PRF with multiple growth factors was obtained by centrifugating the patient’s blood at a specific speed (Figure 3A), and it was adapted to the area (Figure 3B). This is beneficial for promoting healing and increasing the thickness of keratinized gingiva. Second, the XCM membrane (Mucograft®, Geistlich, Switzerland, 15 mm × 20 mm) was trimmed (Figure 3C) and used to cover the wound above the PRF (Figure 3D), when it contacted with blood, thick loosened graft material can become thin and elastic, and it is good for suture fixation. No intensions and folds were made to exert external forces on the matrix in an attempt to cover the wound surface without disturbing its tridimensional structure.

Following the surgery, the patient was administered antibiotics (oral administration, amoxicillin 500 mg TID, metronidazole 300 mg TID) for 3 d to prevent bacterial infection. During the first 2 wk, the patient was informed not to brush the treated area, but rather to rinse the area with 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day.

Three days after the operation, we observed that the edge of the wound was slightly red and swollen but without infection, the surface of the wound was covered with a pseudomembrane, and the patient had no feelings of abnormality (Figure 4A). The sutures were removed after 10 days. The patient was checked at 5 d (Figure 4B), 10 d (Figure 4C), and 1 mo (Figure 5A) after the surgery.

Over time, the grafts tended to become absorbed, and the keratinized gingiva gradually grew along the Mucograft® surface until the wound closed.

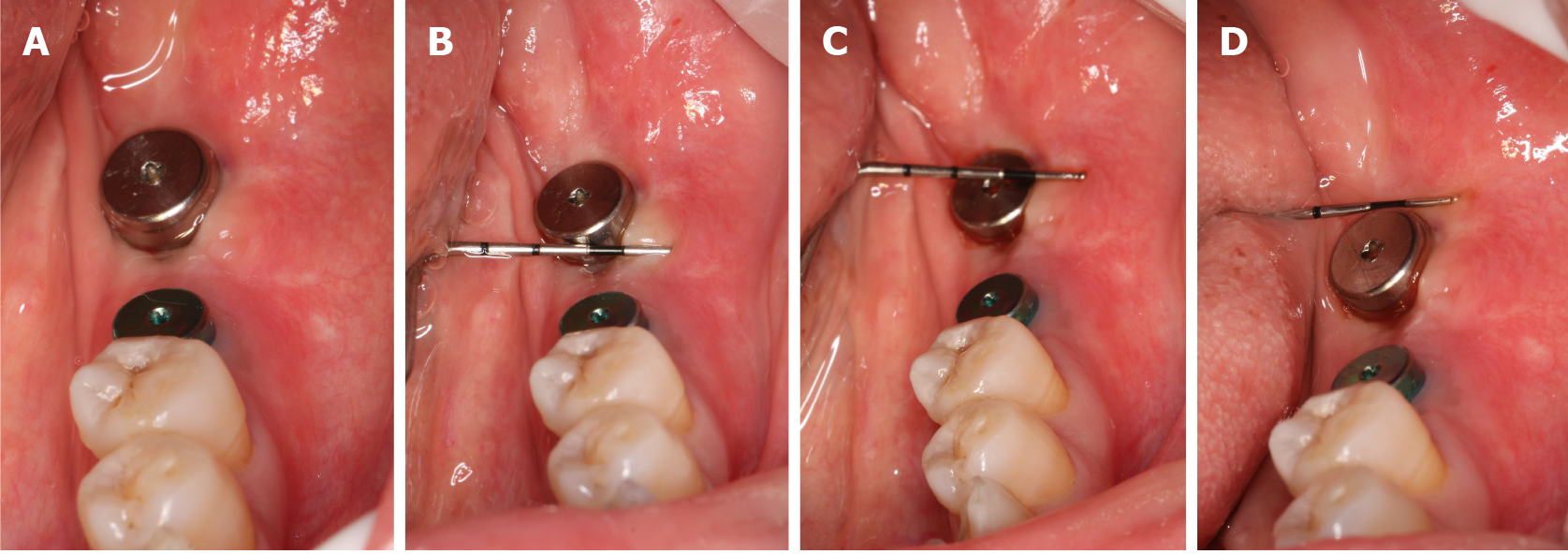

After 4 wk, the wound was well-healed and the width and thickness of the keratinized gingiva reached 4 mm (Figure 5A) and 4.5 mm (Figure 5B), which was suitable for regular stage II surgery. Finally, the keratinized gingiva around the healing abutment was healthy, adequate and consistent with adjacent tissue (Figure 6A). As indicated by the periodontal probe measurement, the width of the buccal keratinized gingiva from mesial to distal reached 4 mm, 4 mm and 3 mm, respectively (Figure 6B-D). The patient was satisfied with the final esthetic outcomes and the discomfort level was acceptable in terms of the pain, swelling, bleeding and chewing activity during the first healing period (Table 1).

| Pain (10 scores) | Bleeding (10 scores) | Time (10 scores) | Outcomes (10 scores) |

| 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

There is junctional epithelium around the dental cervix and many sharpey fibers between the cementum and alveolar bone, so nature teeth exhibit a stronger ability to defend against mechanical and bacterial stimulation. In contrast, dental implants are wrapped annularly by connective tissue, relying only on hemidesmosome connections[6]. Peri-implant gingiva is so easy to move, thereby causing peri-implantitis that is attributed to bacterial invasion[7]. From another perspective, the attached gingiva of healthy teeth is composed of keratinized gingiva. The epidermis layer of keratinized gingiva is stratified squamous epithelium, and the keratinized layer is full of keratinocytes. Epithelial nails were suggested to exist in the lamina propria. It is precisely because of this tissue structure that the mobility of the keratinized gingiva and nonkeratinized gingiva is different, and the former can better protect periodontal health[8,9].

With the extension of tooth missing time, keratinized gingiva tends to decrease, and the patients of this type should generally restore missing teeth along with keratinized gingiva augmentation. ARF is the earliest technique that has been applied to increase the keratinized gingiva around implants. The half-thick flap is opened through horizontal internal oblique incision and bilateral vertical incision, pushed apically and then sutured and fixed, so the exposed periosteal area can self- heal and form keratinized gingiva[10]. Basegmez et al[11] demonstrated that the application of ARF increased keratinized tissue by 1.15 mm at 1 year after the operation, although operation process was simple and time-saving, the postoperative tissue contraction was severe and the augmentation effect was unstable. To prevent tissue contraction, stability and curative effect predictability, clinicians attempted to combine ARF with free gingival graft (FGG) or connective tissue graft (CTG), and the research demonstrated that combined application could achieve more effective outcomes, although there are some serious shortcomings (e.g., limited autograft tissue, second operation area, risks of pain and infection, texture and color differences after the transplantation). Therefore, clinicians’ and patients’ choices should be limited to a certain extent. In the era of "patient-centered" medical treatment, while pursuing the results, the indicators of pain and satisfaction also need to be considered, therefore, clinicians are seeking an alternative to FGG or CTG[12]. Currently, acellular dermal matrix (ADM) and XCM are extensively accepted as soft tissue substitutes that are in the market. The ADM was originally applied to cover burn wounds and diabetic ulcer wounds, increase keratinized gingiva, deepen vestibular sulcus, cover dental root exposure, etc.[13]. However, as demonstrated from several clinical studies, some cases of recession occurred in the long term[14]. The other option is the XCM, a porcine absorbable XCM membrane, consisting of collagen type I and type III, a double-layer structure with one side as a porous layer for cell growth, early vascular discourse and tissue integration, and the other is a smooth and dense layer to facilitate cell adhesion and wound protection[15,16]. A randomized, controlled clinical trial by Cairo et al[17] showed that XCM and CTG obtained similar amounts of apical-coronal keratinized tissue after 6 mo, and XCM was correlated with shorter surgical time, lower postoperative morbidity, less anti-inflammatory tablet consumption and higher final patient satisfaction than those of CTG. At present, increasing the width of keratinized gingiva by ARF combined with XCM is still being explored. Biological graft substitutes are so expensive that autologous biological products can be employed to perform an economic treatment for patients, and PRF, the second generation platelet concentrate reported by Dohan et al[18] is one of the representatives, covering abundant autologous growth factors that facilitate cell proliferation and migration. Its three-dimensional (3D) fibrin network is close to the physiological state, which can promote neovascularization, and wound healing and accelerate tissue remodeling[19].

The principle of increasing keratinized gingiva of XCM refers to guiding the growth of keratinized tissue cells and fibroblasts from the edge to center by exploiting its unique 3D scaffold[20]. Therefore, the incision design should maximize the reservation of keratinized tissue, which contributes to keratinized tissue cell migration from the edge of the incision. In the case of this study, because of the severe atrophy of the buccal keratinized gingiva, the incision was slightly inclined to the lingual side, which means that certain keratinized tissue was reserved on both sides of the incision. Moreover, we did not use a vertical incision, just a simple oblique incision to maintain the blood supply. Most of the blood vessels in the gingiva are parallel to the gingival margin from back to front[21]. This is a modified ARF as a reference[22]. As a result of long-term edentulous, the alveolar ridge atrophied, the vestibular sulcus became shallow, and the positions of the frenulum and muscle varied and were higher, thereby increasing the difficulty of the operation. In addition, the vertical width of XCM implantation was limited. Thus, the muscle attachment was partially relaxed during the operation, and then the semi-thick flap was fixed to the root with protein thread to stabilize the implantation area of XCM. Furthermore, three PRFs were added under the Mucograft® to promote tissue healing, increase the thickness of keratinized gingiva, and lay the foundation for the later cuff depth[23]. The final Mucograft® exhibited open healing, thereby promoting the keratinized cells on both sides of the incision to migrate to the center and proliferate. The increased keratinized gingiva was consistent with the surrounding tissues. The average width of buccal keratinized gingiva was nearly 4 mm, and the patient satisfaction also reached 8 points on average (Table 1).

A modified ARF combined with XCM and PRF, as an alternative to FGG, was adopted to increase the keratinized gingiva in the posterior area in the mandible, and the outcomes were satisfactory. The width of keratinized tissue increased from 0.5 mm to 4 mm. It was demonstrated that this method could have a certain curative effect. For some cases meeting the indications, this method could be selected for soft tissue augmentation. Moreover, subsequent exploration will be conducted with a longer tracking time and more case summaries.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Meng WY S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Vlachodimou E, Fragkioudakis I, Vouros I. Is There an Association between the Gingival Phenotype and the Width of Keratinized Gingiva? Dent J (Basel). 2021;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Fu JH, Wang HL. Breaking the wave of peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000. 2020;84:145-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chackartchi T, Romanos GE, Sculean A. Soft tissue-related complications and management around dental implants. Periodontol 2000. 2019;81:124-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang JP, Liu JM, Wu YM, Chen LL, Ding PH. Efficacy of xenogeneic collagen matrix in the treatment of gingival recessions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2019;25:996-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ibraheem W. Effect of Platelet-rich Fibrin and Free Gingival Graft in the Treatment of Soft Tissue Defect preceding Implant Placement. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19:895-899. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Bartold PM, Walsh LJ, Narayanan AS. Molecular and cell biology of the gingiva. Periodontol 2000. 2000;24:28-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kungsadalpipob K, Supanimitkul K, Manopattanasoontorn S, Sophon N, Tangsathian T, Arunyanak SP. The lack of keratinized mucosa is associated with poor peri-implant tissue health: a cross-sectional study. Int J Implant Dent. 2020;6:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shahramian K, Gasik M, Kangasniemi I, Walboomers XF, Willberg J, Abdulmajeed A, Närhi T. Zirconia implants with improved attachment to the gingival tissue. J Periodontol. 2020;91:1213-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Monje A, Blasi G. Significance of keratinized mucosa/gingiva on peri-implant and adjacent periodontal conditions in erratic maintenance compliers. J Periodontol. 2019;90:445-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | 11 Sethiya KR, Dhadse PV. Healing after Periodontal Surgery - A Review. J Evolution Med Dent Sci. 2020;9:3753-3759. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Basegmez C, Ersanli S, Demirel K, Bölükbasi N, Yalcin S. The comparison of two techniques to increase the amount of peri-implant attached mucosa: free gingival grafts versus vestibuloplasty. One-year results from a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2012;5:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McGuire MK, Scheyer ET, Lipton DI, Gunsolley JC. Randomized, controlled, clinical trial to evaluate a xenogeneic collagen matrix as an alternative to free gingival grafting for oral soft tissue augmentation: A 6- to 8-year follow-up. J Periodontol. 2021;92:1088-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wainwright DJ. Use of an acellular allograft dermal matrix (AlloDerm) in the management of full-thickness burns. Burns. 1995;21:243-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 562] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fischer KR, Testori T, Wachtel H, Mühlemann S, Happe A, Del Fabbro M. Soft tissue augmentation applying a collagenated porcine dermal matrix during second stage surgery: A prospective multicenter case series. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2019;21:923-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moraschini V, de Almeida DCF, Sartoretto S, Bailly Guimarães H, Chaves Cavalcante I, Diuana Calasans-Maia M. Clinical efficacy of xenogeneic collagen matrix in the treatment of gingival recession: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Odontol Scand. 2019;77:457-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | González-Serrano J, López-Pintor RM, Sanz-Sánchez I, Paredes VM, Casañas E, de Arriba L, Vallejo GH. Surgical Treatment of a Peripheral Ossifying Fibroma and Reconstruction with a Porcine Collagen Matrix: A Case Report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2017;37:443-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cairo F, Barbato L, Tonelli P, Batalocco G, Pagavino G, Nieri M. Xenogeneic collagen matrix versus connective tissue graft for buccal soft tissue augmentation at implant site. A randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:769-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, Gogly B. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e37-e44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 776] [Cited by in RCA: 1010] [Article Influence: 53.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Serafini G, Lopreiato M, Lollobrigida M, Lamazza L, Mazzucchi G, Fortunato L, Mariano A, Scotto d'Abusco A, Fontana M, De Biase A. Platelet Rich Fibrin (PRF) and Its Related Products: Biomolecular Characterization of the Liquid Fibrinogen. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Naenni N, Walter P, Hämmerle CHF, Jung RE, Thoma DS. Augmentation of soft tissue volume at pontic sites: a comparison between a cross-linked and a non-cross-linked collagen matrix. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:1535-1545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shahbazi A, Feigl G, Sculean A, Grimm A, Palkovics D, Molnár B, Windisch P. Vascular survey of the maxillary vestibule and gingiva-clinical impact on incision and flap design in periodontal and implant surgeries. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:539-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Carnio J, Camargo PM. The modified apically repositioned flap to increase the dimensions of attached gingiva: the single incision technique for multiple adjacent teeth. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2006;26:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lektemur Alpan A, Torumtay Cin G. PRF improves wound healing and postoperative discomfort after harvesting subepithelial connective tissue graft from palate: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24:425-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |