Published online Dec 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10708

Peer-review started: June 6, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: July 7, 2021

Accepted: August 23, 2021

Article in press: August 23, 2021

Published online: December 6, 2021

Processing time: 176 Days and 20.7 Hours

Aggressive natural killer cell leukemia (ANKL) is a rare natural killer cell neoplasm characterized by systemic infiltration of Epstein–Barr virus and rapidly progressive clinical course. ANKL can be accompanied with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Here, we report a case of ANKL with rare skin lesions as an earlier manifestation, accompanied with HLH, and review the literature in terms of etiology, clinical manifestation, diagnosis and treatment.

A 30-year-old woman from Northwest China presented with the clinical characteristics of jaundice, fever, erythema, splenomegaly, progressive hemocytopenia, liver failure, quantities of abnormal cells in bone marrow, and associated HLH. The immunophenotypes of abnormal cells were positive for CD2, cCD3, CD7, CD56, CD38 and negative for sCD3, CD8 and CD117. The diagnosis of ANKL complicated with HLH was confirmed. Following the initial diagnosis and supplementary treatment, the patient received chemotherapy with VDLP regimen (vincristine, daunorubicin, L-asparaginase and prednisone). However, the patient had severe adverse reactions and complication such as severe hematochezia, neutropenia, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and died a few days later.

This is the first reported case of ANKL with rare skin lesions as an earlier manifestation and associated with HLH.

Core Tip: Aggressive natural killer cell leukemia (ANKL) is a rare natural killer (NK) cell neoplasm characterized by systemic infiltration of Epstein–Barr virus and rapid development. Diagnosis and treatment of ANKL can be challenging due to its rapid development, rare nature, and varied clinical manifestations. Extranodal nasal NK/T cell leukemia, indolent NK cell lymphoproliferative disease, and T-large granular lymphoblastic leukemia must be considered in differential diagnosis. Standard therapy for ANKL has not been established because of its rare nature, rapid development, and poor prognosis. This is the first reported case of ANKL associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and rare skin lesions simultaneously.

- Citation: Peng XH, Zhang LS, Li LJ, Guo XJ, Liu Y. Aggressive natural killer cell leukemia with skin manifestation associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(34): 10708-10714

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i34/10708.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10708

Aggressive natural killer cell leukemia (ANKL) is a rare mature natural killer (NK) cell malignant lymphoproliferative disease associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection[1]. In general, patients with ANKL present with systemic symptoms, pancytopenia and hepatosplenomegaly. The skin lesion as an earlier manifestation of ANKL is very rare. ANKL runs an aggressive course and is usually rapidly fatal, with a median survival of only 2 mo[2]. Only early diagnosis, active control of complications, prevention of further deterioration of the disease, and effective chemotherapy can win time for the survival of patients. We report the case of a 30-year-old that was diagnosed as ANKL associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

A 30-year-old female patient presented to our Department of Hematology Medicine complaining of fatigue, abdominal distension for 1 mo, and yellow staining of skin and scattered erythema for 10 d.

She had been treated with antibiotics and Chinese patent drug for 3 d for a cold before admission to our hospital. However, the symptoms were not significantly improved. Abdominal distension became more serious with nausea and vomiting, then yellow staining and dense flaky erythema appeared across the whole body skin, mucous membranes and sclera. She was presented to our hospital.

There was no history of past illness.

She and her family had no specific disease history. Both parents and one older brother were in good health.

Physical examination revealed that the whole skin, mucous membranes and sclera were yellow stained, and dense flaky erythema with scattered bleeding spots of different sizes were found on the forehead, behind the ears, neck and chest (Figure 1A), and the liver and spleen were obviously enlarged.

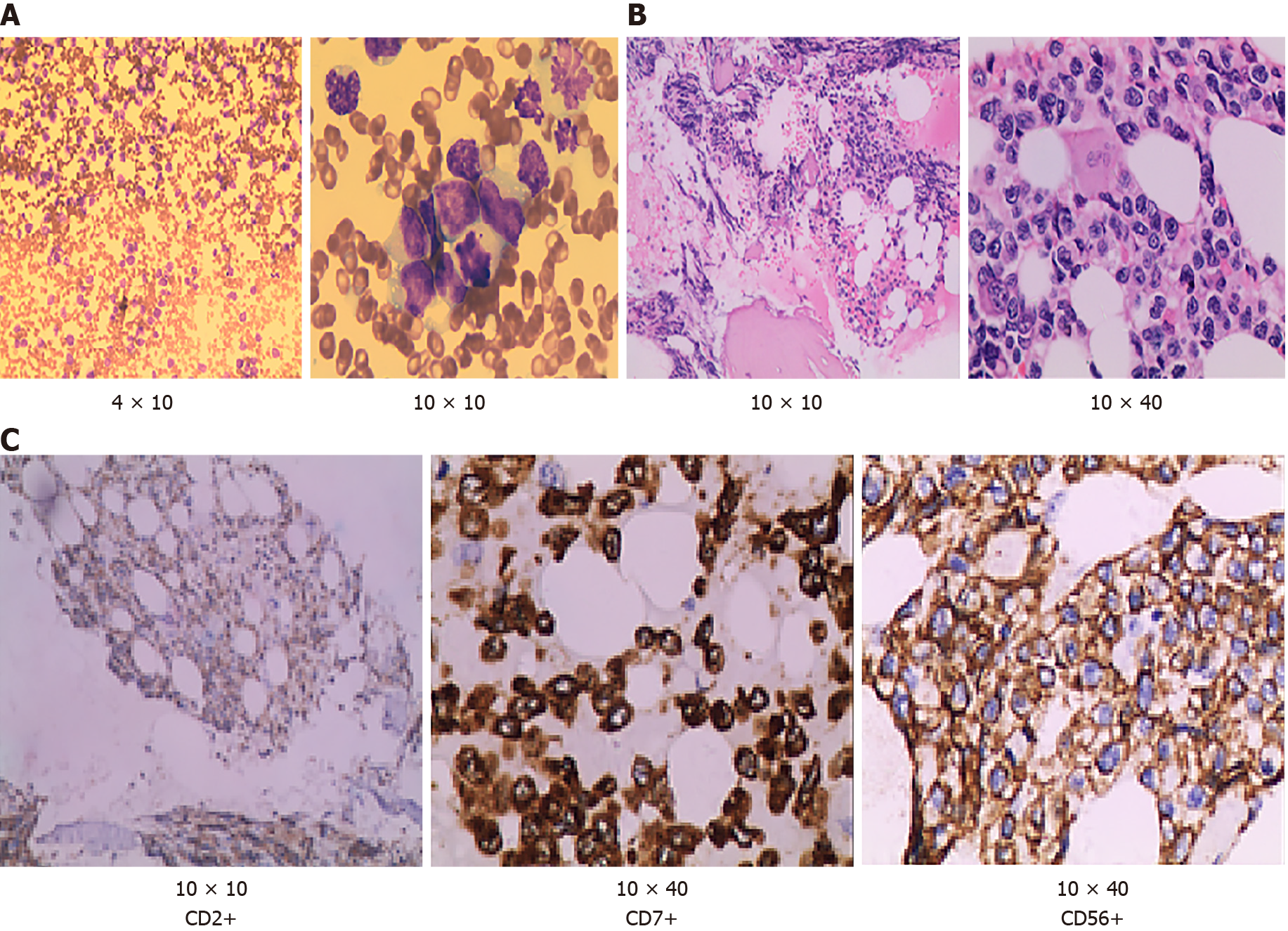

The blood cell counts were as follows: hemoglobin (HGB) 97 g/L, platelets (PLTs) 15 × 109/L and leukocytes 22.92 × 109/L. Biochemical tests showed marked increased level of total bilirubin to 250.6 μmol/L, direct bilirubin to 221.6 μmol/L, alanine transaminase to 270 U/L, aspartate transaminase to 341 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase to 8527 U/L, and marked decreased level of the total protein to 53.1 g/L. The laboratory findings also found coagulopathy [high level of D-dimer (1.51 μg/mL) and fibrinogen degradation product (5.70 μg/mL)]. Bone marrow aspiration showed that cells with unknown classification and abnormality were easy to see, accounting for 94% (Figure 2A). Bone marrow biopsy test showed that hematopoietic tissue proliferation was heterogeneous, granulocyte and erythrocytic proliferation were decreased, megakaryocytic hyperplasia (0–4/high-power field) was scattered (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemistry of bone marrow biopsy showed that these atypical cells were positive for cCD3, CD20, CD34, CD68, CD56, CD2, CD7, and negative for sCD3 (Figure 2C). Serological tests for EBV revealed that EBV DNA was 7.22 ´ 106 copies. Multicolor flow cytometry revealed that abnormal cell populations of 90% were seen in areas where CD45 was strongly positive, expressing HLA-DR, CD2, CD7, CD38 and cCD3, and partially expressing CD56. Abnormal NK cells could be seen in the samples, considering the possible source of NK/T cells. TCR gene rearrangement test was negative.

Positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) of the whole body showed that metabolism was increased in multiple parts (Figure 1B). PET/CT revealed that malignant tumor cells of the lymphoid hematopoietic system accumulated in multiple organs.

According to the clinical manifestation, laboratory and imaging examination, the patient was diagnosed with ANKL associated with HLH[3].

Following the initial diagnosis and supplementary treatment of malignant tumors, such as transfusion of gammaglobulin, HGB, plasma and PLTs, the patient underwent chemotherapy with VDLP regimen (vincristine, daunorubicin, L-asparaginase and prednisone).

The patient had severe stomachache and vomiting on the second day of chemotherapy, and symptomatic support treatment such as proton pump inhibitor and antiemetic was given. On the third day of chemotherapy, severe hematochezia occurred. Blood pressure began to decrease; heart rate increased to 180 beats/min, HGB, and leukocyte and PLT counts were extremely low, especially PLTs. Considering ANKL complicated with HLH, neutropenia, myelosuppression, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit. The general condition of the patient did not improve and deteriorated. Finally, the patient died a few days later.

ANKL is a rare entity with < 200 cases published to date, and is always associated with EBV infection[1]. In 1986, Suzuki et al[4] put forward the concept of ANKL for the first time. In 2001, the World Health Organization classified it as ANKL in the classification of lymphoid tissue tumors, and extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma and extranodal nasal NK/TX cell leukemia (ENKTCL) were both mature NK cell tumors[5]. With the emergence of the next generation of sequencing technology, the molecular basis of ANKL has been clarified. In recent years, the introduction of combined chemotherapy including L-asparaginase (L-ASP), and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, has helped some patients achieve complete remission and potential cure in theory[6]. However, the prognosis of ANKL is still poor, with a median survival time of 2 mo[7].

ANKL is a systemic disease; the main clinical symptoms are obvious B symptoms, including high fever, fatigue, night sweats, loss of appetite, weight loss, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly[8]. The blood cell counts are mostly one-line or multi-line progressive decrease, and the activity of serum lactate dehydrogenase and FASL levels are often high[9]. ANKL is often associated with HLH. Compared with ENKTCL, skin damage is rare[8]. The course of the disease is outbreak, usually accompanied by diffuse intravascular coagulation, leading to multiple organ failure, which progresses to death within a few weeks.

At present, there are no unified diagnostic criteria for ANKL and the more recognized diagnostic criteria are: (1) More immature large granular leukocytes in peripheral blood and bone marrow; (2) Rapidly progressive B symptoms, liver, spleen and lymph node enlargement, neutropenia, low HGB, thrombocytopenia, liver function and blood coagulation abnormalities; (3) EBV antibody or DNA positive; (4) Immunophenotype conforms to CD2+ CD56+ sCD3 TCRαβ TCRγδ; (5) Common chromosomal abnormalities del; and (6) q21q25[10]. The genetic changes of ANKL are largely unknown, which is in sharp contrast to the rich genetic information of ENKTCL; a disease closely related to ANKL. Some gene mutations in ANKL, including the JAK–STAT and Ras–MAPK systems, are found in the signal transduction system. Some studies have shown that the frequent mutations in the JAK–STAT signaling system are STAT3 or STAT5B. STAT3 represents the most frequently mutated gene (~20% of cases)[11]. Tumor suppressor genes TP53 and DDX3X, epigenetic modification genes CREBBP, TET2, MLL2, BCOR and SETD2 and hypermethylation mutation of HACE1 have also been described in ANKL[12]. However, in terms of clinical practice, the diagnosis of ANKL still depends to a large extent on leukemic cells with abnormal morphology and immunophenotype. Chromosome gain and loss, STAT3 and STAT5B mutations, and HACE1 hyperme

HLH is also a rare hematological disease, but it is one of the common complications of ANKL. In one published study, there were 34 patients with ANKL, of which 19 (56%) developed HLH during the course of treatment[13]. It was secondary HLH because it was secondary to NK cell leukemia.

Initially, a large area of dense flaky erythema with scattered bleeding spots of different sizes appeared on the forehead, behind the ears, neck and chest. We found no relevant reports in the literature. It has been reported that skin lesions in ANKL are relatively rare compared with ENKTCL[7], but skin lesions were found in the present case. The patient died due to rapid progression of the disease; therefore, we lost the opportunity to clarify the nature of the skin lesions and their relationship with the primary disease. The systemic invasion of tumor cells in this patient was obvious, so it can be speculated that the condition was complicated with rare skin lesions.

At present, there are no unified clinical treatment standards or prospective clinical trials specifically for ANKL. The widely accepted clinical chemotherapy regimens are: CHOP-like regimen (including anthracycline and vincristine), L-ASP + methotrexate + dexamethasone regimen, SMILE (dexamethasone + methotrexate + ifosfamide + L-ASP + VP16) regimen, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia intensive chemotherapy (VDLP) regimen[10]. Some studies have shown that the high expression of P-glycoprotein encoded by multidrug resistance gene MDR1 in NK tumor cells may be related to the poor response of ANKL to chemotherapy and relapse after chemo

In the present case of ANKL complicated with HLH, disease progression was rapid. According to current research, it was suggested that SMILE or L-ASP + methotrexate + dexamethasone regimen should be used to control the primary disease, but consi

ANKL is still a challenging disease due to its rapid development, rare nature, and variety of clinical manifestations. Therefore, only early diagnosis, active control of complications, prevention of further deterioration of the disease, and effective chemotherapy can win time for the survival of patients.

We are thankful to the family of the patient for permitting us to use their case for presentation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Hematology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Azmi AS S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor:Guo X

| 1. | Lima M. Aggressive mature natural killer cell neoplasms: from epidemiology to diagnosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Suzuki R, Suzumiya J, Yamaguchi M, Nakamura S, Kameoka J, Kojima H, Abe M, Kinoshita T, Yoshino T, Iwatsuki K, Kagami Y, Tsuzuki T, Kurokawa M, Ito K, Kawa K, Oshimi K; NK-cell Tumor Study Group. Prognostic factors for mature natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms: aggressive NK cell leukemia and extranodal NK cell lymphoma, nasal type. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1032-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3075] [Cited by in RCA: 3579] [Article Influence: 198.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Suzuki R, Suzumiya J, Nakamura S, Aoki S, Notoya A, Ozaki S, Gondo H, Hino N, Mori H, Sugimori H, Kawa K, Oshimi K; NK-cell Tumor Study Group. Aggressive natural killer-cell leukemia revisited: large granular lymphocyte leukemia of cytotoxic NK cells. Leukemia. 2004;18:763-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chan JK. The new World Health Organization classification of lymphomas: the past, the present and the future. Hematol Oncol. 2001;19:129-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ishida F, Ko YH, Kim WS, Suzumiya J, Isobe Y, Oshimi K, Nakamura S, Suzuki R. Aggressive natural killer cell leukemia: therapeutic potential of L-asparaginase and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1079-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Gill H, Liang RH, Tse E. Extranodal natural-killer/t-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Adv Hematol. 2010;2010:627401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gao LM, Zhao S, Liu WP, Zhang WY, Li GD, Küçük C, Hu XZ, Chan WC, Tang Y, Ding WS, Yan JQ, Yao WQ, Wang JC. Clinicopathologic Characterization of Aggressive Natural Killer Cell Leukemia Involving Different Tissue Sites. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:836-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tse E, Kwong YL. The diagnosis and management of NK/T-cell lymphomas. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ishida F, Kwong YL. Diagnosis and management of natural killer-cell malignancies. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3:593-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Huang L, Liu D, Wang N, Ling S, Tang Y, Wu J, Hao L, Luo H, Hu X, Sheng L, Zhu L, Wang D, Luo Y, Shang Z, Xiao M, Mao X, Zhou K, Cao L, Dong L, Zheng X, Sui P, He J, Mo S, Yan J, Ao Q, Qiu L, Zhou H, Liu Q, Zhang H, Li J, Jin J, Fu L, Zhao W, Chen J, Du X, Qing G, Liu H, Liu X, Huang G, Ma D, Zhou J, Wang QF. Integrated genomic analysis identifies deregulated JAK/STAT-MYC-biosynthesis axis in aggressive NK-cell leukemia. Cell Res. 2018;28:172-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nakashima Y, Tagawa H, Suzuki R, Karnan S, Karube K, Ohshima K, Muta K, Nawata H, Morishima Y, Nakamura S, Seto M. Genome-wide array-based comparative genomic hybridization of natural killer cell lymphoma/Leukemia: different genomic alteration patterns of aggressive NK-cell leukemia and extranodal Nk/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;44:247-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nicolae A, Ganapathi KA, Pham TH, Xi L, Torres-Cabala CA, Nanaji NM, Zha HD, Fan Z, Irwin S, Pittaluga S, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. EBV-negative Aggressive NK-cell Leukemia/Lymphoma: Clinical, Pathologic, and Genetic Features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jaccard A, Gachard N, Marin B, Rogez S, Audrain M, Suarez F, Tilly H, Morschhauser F, Thieblemont C, Ysebaert L, Devidas A, Petit B, de Leval L, Gaulard P, Feuillard J, Bordessoule D, Hermine O; GELA and GOELAMS Intergroup. Efficacy of L-asparaginase with methotrexate and dexamethasone (AspaMetDex regimen) in patients with refractory or relapsing extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, a phase 2 study. Blood. 2011;117:1834-1839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ando M, Sugimoto K, Kitoh T, Sasaki M, Mukai K, Ando J, Egashira M, Schuster SM, Oshimi K. Selective apoptosis of natural killer-cell tumours by l-asparaginase. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:860-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kwong YL, Kim WS, Lim ST, Kim SJ, Tang T, Tse E, Leung AY, Chim CS. SMILE for natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: analysis of safety and efficacy from the Asia Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2012;120:2973-2980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |