Published online Dec 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10638

Peer-review started: December 24, 2020

First decision: July 8, 2021

Revised: July 18, 2021

Accepted: October 20, 2021

Article in press: October 20, 2021

Published online: December 6, 2021

Processing time: 341 Days and 2 Hours

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare degenerative disease of the central nervous system that can be contagious or hereditary and is a rare cause of rapidly progressive dementia. It almost always results in death within 1-2 years from symptom onset.

Here, we report the case of a 57-year-old male who initially experienced dizziness followed by a 1-mo fast decline in memory function. He presented to the local hospital and underwent magnetic resonance imaging and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination, with no definitive diagnosis. However, the symptoms of progressive forgetting worsened. In addition, he exhibited progressive involuntary tremor of the limbs. Then, he came to our hospital, and according to the results of CSF examination, electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tests and clinical manifestations of cerebellar ataxia, dementia, and myoclonus that rapidly progressed, with a short duration of illness, he was finally diagnosed with sporadic CJD (sCJD).

This case report aims to create awareness among physicians to emphasize auxiliary examination, CSF examination, EEG and MRI tests and recognition of cerebellar ataxia, dementia, and myoclonus that rapidly progress to prompt pursuit of an early diagnosis and identification of sCJD and to reduce complications.

Core Tip: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare degenerative disease of the central nervous system that can be contagious or hereditary and is a rare cause of rapidly progressive dementia. Here, we report the case of a 57-year-old male who initially experienced dizziness followed by a 1-mo fast decline in memory function. According to the cerebrospinal fluid examination, electroencephalography, and, magnetic resonance imaging tests and cerebellar ataxia, dementia, and myoclonus that rapidly progressed, with a short duration of illness Clinical manifestations then he was finally diagnosed with sporadic CJD (sCJD). This case reports aim to create awareness amongst physicians to emphasize the importance of pursuing an early diagnosis and identifying sCJD and reducing complications.

- Citation: Xu YW, Wang JQ, Zhang W, Xu SC, Li YX. Rarely fast progressive memory loss diagnosed as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(34): 10638-10644

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i34/10638.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10638

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare neurodegenerative disorder and the most common prion disease in humans; it is characterized by severe nervous system damage and high mortality[1]. The prion hypothesis proposed by Prusiner in 1982 is now widely accepted, by which CJD pathogenesis involves the conversion of normal cellular prion protein (PrP) to pathogenic forms[2]. The mechanism for triggering this conformational change is unknown, but abnormal PrP leads to neuronal degeneration, astrocytic gliosis, and spongiform changes, accompanied by rapid cognitive decline and death[3]. Four types of CJD are known thus far: sporadic, genetic/familial, iatrogenic, and variant[4]. Sporadic CJD (sCJD) cases account for ~85% of CJD and are considered among the most fatal neurological disorders[5]. The characteristic clinical picture of CJD is rapidly progressive dementia accompanied by behavioral disturbances, ataxia, and myoclonus[6]. Here, we report a case of sCJD with progressive memory loss. The aim is to enrich the clinical data and to provide a reference for improving the diagnosis and prognosis of this disease. At the same time, clinicians will be better informed about typical CJD.

A month prior to admission to our hospital, a 57-year-old man was admitted to the local hospital with dizziness, obvious memory loss, and rapidly progressive dementia.

A month prior to admission to our hospital, a 57-year-old man was admitted to the local hospital with dizziness, obvious memory loss, and rapidly progressive dementia.

The patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that showed an abnormality in the head of the right caudate nucleus suggesting multiple lacunar infarctions.

Denial the family history of infectious diseases.

The patient was admitted to our department following 1 mo of progressive memory loss accompanied by disturbed consciousness, dementia, depression, and inability to answer questions or complete physical examinations. Based on the reports of the patient’s family and a review of records, the patient’s gait changes, instability, aphasia, forgetfulness, hyperdystonia, and weight loss were all exacerbated since the initial hospital admission. The muscle tone of limbs increased significantly and became hyperactive. Pathological reflex examination revealed positive Babinski and Chaddock signs. There were no other positive neurological signs.

A month prior to admission to our hospital, the patient was examined at the local hospital according to the test results provided by the patient. The results of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed an elevated albumin level of 760 mg/L (nominal range 120-600 mg/L). No definitive diagnosis was made. When his progressive amnesia worsened, the patient was transferred to our hospital for further treatment. We conducted basic laboratory tests, including C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, full blood cell count, and electrocardiogram. Microbiological assays were negative, including screening tests for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, and neurosyphilis. Immunological tests were also normal (Table 1).

| Laboratory tests | Result | Reference values |

| Anti-Hu antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-CV2 antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Ri antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Ma2 antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Yo antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-ANNA-3 antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Tr antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-PCA-2 antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

To further clarify the diagnosis, we performed a second CSF examination. Cytology and biochemical parameters were within normal limits, but glucose and protein levels were slightly elevated (Table 2). The CSF virus test and bacterial culture were negative, allowing us to rule out central infectious diseases.

| Laboratory tests | Result | Reference values |

| Colour | Colorless | Colorless |

| Transparency | Transparent | Transparent |

| Pan's experiment | Positive | Negative |

| WBC count, × 106/L | 2 | < 8 |

| RBC count, × 106 | 22 | 0 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid glucose, mmol/L | 5.43 | 2.2-3.9 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid protein, mmol/L | 715 | 120-600 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid chloride, mmol/L | 125.4 | 120-132 |

| Rubella virus IgG, IU/mL | 0.68 | < 10 |

| Anti-rubella virus IgM, COI | 0.32 | < 1.0 |

| Cytomegalovirus IgG, IU/mL | 6.71 | < 1.0 |

| Cytomegalovirus IgM, COI | 0.16 | < 1.0 |

| Epstein-Barr virus antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Coxsackie virus antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Negative | Negative |

| Nacterial smear (gram stain) | No | No |

| Acid-fast bacilli | No | No |

To rule out the possibility of a central tumor, an examination of paraneoplastic syndrome was actively carried out. The patient was examined before being readmitted to the hospital. Paraneoplastic syndrome (PNS) is an autoimmune syndrome caused by anti-neuron antibodies. Paraneoplastic syndrome should be considered if the patient shows dementia, extrapyramidal or cerebellar symptoms or other neurological symptoms, subacute onset or rapid progression, positive cerebrospinal fluid inflammatory markers, tumor risk factors or tumor family history[7]. The common antibodies are anti-Hu, anti-CV2, anti-Ri, anti-Ma2, anti-Yo, anti-NMDAR and anti-AMPAR antibodies. Different antibodies can indicate corresponding potential tumors. The most common disease associated with paraneoplastic syndrome is marginal lobular encephalitis, also known as paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis. Usually, the related antibodies are anti-Hu, anti-CV2, anti-Ma2, anti-Ri, and anti-Yo antibodies[8]. The patient was examined for paraneoplastic syndrome to find positive antibodies (Table 3).

| Laboratory tests | Result | Reference values |

| Anti- Hu antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-CV2 antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Ri antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Ma2 antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Yo antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-ANNA-3 antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Tr antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-PCA-2 antibody IgG | Negative | Negative |

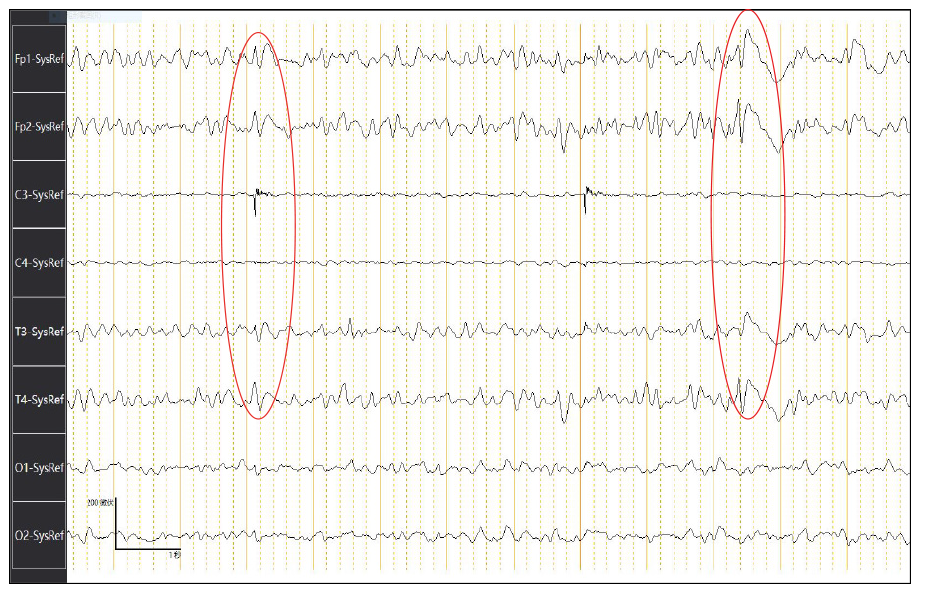

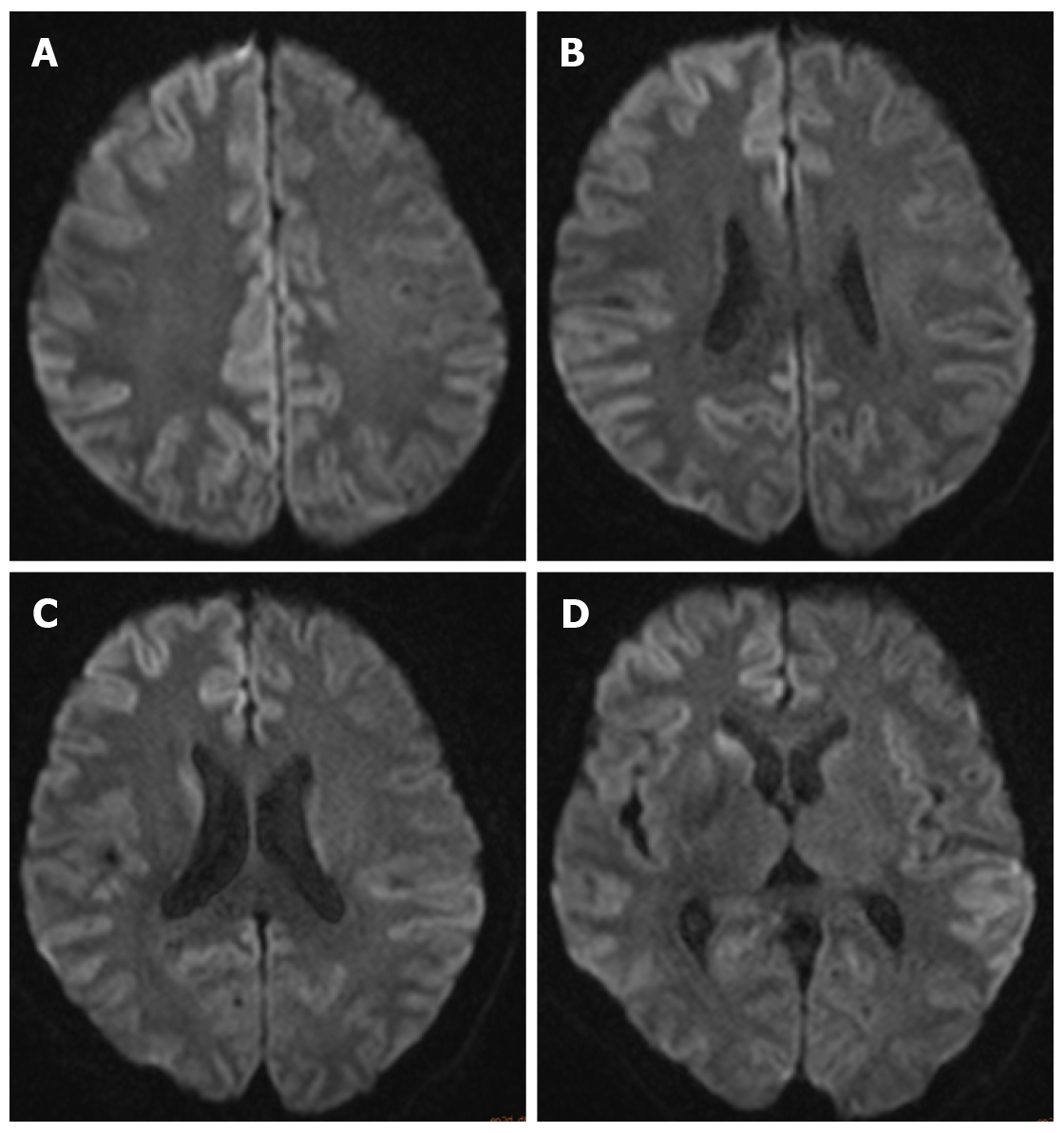

Electroencephalography (EEG) showed generalized periodic sharp wave complexes and slow background activity. These findings were interpreted as nonspecific, moderate, widespread cortical dysfunction, also involving subcortical structures (Figure 1). Brain MRI showed no hemorrhage, infarction, or mass lesions. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) detected increased signal intensity in the cortex of the right frontal-parietal lobe, part of the left frontal-parietal lobe next to the cerebral falx, cingulate gyrus, and bilateral temporal lobes. In addition, there was a high signal in the head of the left caudate nucleus (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with CJD.

According to the results, the patient’s inflammation index increased, and we carried out active anti-infective therapy, reduced intracranial pressure sedation, increased nutrition, and improved cognitive treatments. To avoid aspiration, treatment of the indwelling gastric tube was carried out. However, the condition did not improve. Brain biopsy was recommended to the family for confirmation of sCJD, but they declined and instead chose supportive care. Although we did not detect 14-3-3 protein, on the basis of clinical features and CSF, MRI, and EEG test results, the patient received a probable diagnosis of sCJD.

The patient’s clinical status deteriorated over the subsequent week. However, the patient’s family opted for withdrawal of care, and he was discharged home.

CJD is a rare and fatal neurodegenerative disorder and represents the most common prion human disease. The pathogenesis of CJD is the conformational transition of a host-encoded cellular PrP into an infectious and pathogenic isoform that propagates in multiple regions of the brain by self-replication[1]. sCJD is the most common human prion disease, accounting for approximately 85% of all cases[9]. It is characterized by neuronal loss, astrogliosis, extensive spongiform degeneration, and deposition of misfolded PrP. The clinical characteristics include rapid progressive dementia, pyramidal tract signs, myoclonus, and psychiatric symptoms. There is a lack of specific symptoms at disease onset, especially psychiatric manifestations and rapid progressive dementia, and patients with CJD can be easily misdiagnosed[10].

Other neurological diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal dementia, chronic course. Sometimes there is an acceleration in the course of the disease, but imaging changes can usually be distinguished. There were no characteristic changes in the head MRI scan, and through early EEG examination, a small number of patients can show a reduction in background wave amplitude, while most patients show a decrease in α waves and transient slow waves in the temporal lobe.

PNS is an autoimmune syndrome caused by anti-neuron antibodies. Diagnosis of PNS can be confirmed by the detection of anti-Hu, anti-CV2, anti-Ri, anti-Ma2, anti-Yo, anti-NMDAR and anti-AMPAR antibodies in the CSF, but in this case, these antibodies were all negative, so we ruled out PNS.

Due to the variable clinical presentation of CJD, which progresses rapidly without obvious clinical specificity, there is a need for prompt diagnosis and supportive treatment to avoid progression and extend the survival time. Our patient initially presented with mild amnesia symptoms, but when he was transferred to our hospital for treatment, the symptoms had progressed. At the same time, there were clinical manifestations indicating pyramidal tract involvement; cerebellar ataxia was the dominant feature at onset, followed by involuntary limb convulsions, which were rapidly followed by focal dystonia.

Clear diagnosis and elimination of other central nervous system diseases are very important for the diagnosis of CJD. Only inflammation indicators were elevated in the present case (Table 1). However, the patient was negative for Epstein-Barr virus antibodies, human immunodeficiency virus and neurosyphilis (Table 2). The second CSF examination ruled out infective encephalopathy, metabolic derangement, and autoimmune encephalopathy; all metabolic parameters were within normal limits. We were also able to rule out Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies based on the patient’s medical history (Table 3).

EEG is an important and integral part of the CJD diagnostic process[11]. EEG recordings revealed gradual slowing of background activity with a more obvious appearance of bihemispheric triphasic waves and nearly typical periodic sharp wave complexes (Figure 1). The EEG diagnostic specificity and sensitivity for CJD are 64% and 91%, respectively[12].

Caobelli et al[12] reported that DWI may be the most sensitive imaging technique for early diagnosis, and MRI in general is the most helpful test for suspected sCJD, as it has excellent specificity and sensitivity[13]. Repeat brain MRI revealed increased signal intensity in the cortex and head of the left caudate nucleus. The typical DWI signal for early diagnosis of CJD is bilateral petal-like changes along the cortical sulcus (Figure 2). MRI has an overall sensitivity of 60%-70% and specificity of 80%-90%[14,15]. It may be particularly reliable and helpful in the clinical diagnosis of patients with certain PrP genotypes.

Periodic sharp wave complexes are reported in EEG recordings of approximately two-thirds of patients with sCJD and are included in the World Health Organization (WHO) (1998) diagnostic classification criteria of sCJD. The diagnostic criteria for probable sCJD are: (1) rapidly evolving dementia (< 2 years); (2) typical periodic sharp wave complexes with triphasic morphology in EEG recordings and/or the presence of 14-3-3 protein in CSF examination; and (3) at least two of the following four clinical signs: (a) myoclonus; (b) ataxia and/or visual signs and symptoms; (c) extrapyramidal and/or pyramidal signs and symptoms; and (d) akinetic mutism. Patients with clinical signs of sCJD but without EEG and CSF abnormalities (either not present or investigation not available) are classified as having possible sCJD.

Some caution in performing autopsy should be mentioned due to the infective nature of prions. Eliminate known infected wounds and properly isolate the patient. There should be no use of contaminated food, and the contaminated equipment must be strictly disinfected. Used medical waste is burned separately.

Performing CSF examination, EEG, MRI, and 14-3-3 protein tests are important in the diagnosis of CJD. With regard to this case, neurological features included cerebellar ataxia, dementia, and myoclonus that rapidly progressed, with a short duration of illness. The patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly over a month, with clinical manifestations of pyramidal tract and memory dysfunction. Based on the patient’s clinical symptoms and EEG and MRI results and the WHO (1998) diagnostic classification criteria of sCJD, we diagnosed CJD.

CJD remains a particularly challenging diagnosis for physicians, mainly because of its rarity and clinical heterogeneity. sCJD is an uncommon and lethal disease that progresses quickly, and there is no effective treatment. Although brain biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis, it is highly invasive, and not every family can accept it. For this reason, noninvasive examination is very important in diagnosis. These tests can be helpful in providing support for early diagnosis, but they do not change the prognosis. This case report aims to create awareness among physicians to emphasize the importance of pursuing an early diagnosis and identifying and reducing complications.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Neurosciences

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Florio T S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Puoti G, Bizzi A, Forloni G, Safar JG, Tagliavini F, Gambetti P. Sporadic human prion diseases: molecular insights and diagnosis. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:618-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Narula R, Tinaz S. Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee J, Hyeon JW, Kim SY, Hwang KJ, Ju YR, Ryou C. Review: Laboratory diagnosis and surveillance of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Med Virol. 2015;87:175-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rosenbloom MH, Atri A. The evaluation of rapidly progressive dementia. Neurologist. 2011;17:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zerr I, Kallenberg K, Summers DM, Romero C, Taratuto A, Heinemann U, Breithaupt M, Varges D, Meissner B, Ladogana A, Schuur M, Haik S, Collins SJ, Jansen GH, Stokin GB, Pimentel J, Hewer E, Collie D, Smith P, Roberts H, Brandel JP, van Duijn C, Pocchiari M, Begue C, Cras P, Will RG, Sanchez-Juan P. Updated clinical diagnostic criteria for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2009;132:2659-2668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morano A, Fanella M, Cerulli Irelli E, Barone FA, Fisco G, Orlando B, Albini M, Fattouch J, Manfredi M, Casciato S, Di Gennaro G, Giallonardo AT, Di Bonaventura C. Seizures in autoimmune encephalitis: Findings from an EEG pooled analysis. Seizure. 2020;83:160-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Macchi ZA, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Orjuela KD, Pastula DM, Piquet AL, Baca CB. Glioblastoma as an autoimmune limbic encephalitis mimic: A case and review of the literature. J Neuroimmunol. 2020;342:577214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fragoso DC, Gonçalves Filho AL, Pacheco FT, Barros BR, Aguiar Littig I, Nunes RH, Maia Júnior AC, da Rocha AJ. Imaging of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: Imaging Patterns and Their Differential Diagnosis. Radiographics. 2017;37:234-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Baiardi S, Capellari S, Bartoletti Stella A, Parchi P. Unusual Clinical Presentations Challenging the Early Clinical Diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:1051-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Appel S, Cohen OS, Chapman J, Gilat S, Rosenmann H, Nitsan Z, Kahan E, Blatt I. The association of quantitative EEG and MRI in Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019;140:366-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zerr I, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Giese A, Bodemer M, Schröter A, Henkel K, Tschampa HJ, Windl O, Pfahlberg A, Steinhoff BJ, Gefeller O, Kretzschmar HA, Poser S. Current clinical diagnosis in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: identification of uncommon variants. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:323-329. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Caobelli F, Cobelli M, Pizzocaro C, Pavia M, Magnaldi S, Guerra UP. The role of neuroimaging in evaluating patients affected by Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a systematic review of the literature. J Neuroimaging. 2015;25:2-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bizzi A, Pascuzzo R, Blevins J, Moscatelli MEM, Grisoli M, Lodi R, Doniselli FM, Castelli G, Cohen ML, Stamm A, Schonberger LB, Appleby BS, Gambetti P. Subtype Diagnosis of Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease with Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Ann Neurol. 2021;89:560-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zeidler M, Collie DA, Macleod MA, Sellar RJ, Knight R. FLAIR MRI in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 2001;56:282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | World Health Organization. The Revision of the Surveillance Case Definition for Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67341/WHO. |