Published online Nov 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9629

Peer-review started: July 15, 2021

First decision: August 19, 2021

Revised: September 1, 2021

Accepted: September 10, 2021

Article in press: September 10, 2021

Published online: November 6, 2021

Processing time: 106 Days and 4.6 Hours

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) is a common precancerous lesion of endometrial carcinoma (EC). The risk factors for AEH and EC directly or indirectly related to estrogen exposure include early menarche, nulliparity, polycystic ovarian syndrome, diabetes, and obesity. Both AEH and EC rarely occur in young patients (< 40-years-old), who may desire to maintain their fertility. Evaluating the cancer risk of AEH patients is helpful for the determination of therapeutic plans.

We report a rare case of AEH in a 35-year-old woman who presented to the Hunan Provincial Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital with a large mass in the uterus. She married at 20-years-old, and had been married for more than 15 years to date. Several characteristics of this patient were observed, including nulliparity, limited sexual activity (intercourse 1-2 times a year) in recent years, and irregular vaginal bleeding for 2 years. Gynecological examination revealed an enlarged uterus, similar to the uterus size in the fourth month of pregnancy, and the uterine wall was relatively hard. Curettage was performed based on transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging results. Findings from the pathological examination were typical for AEH. The patient was cured after treatment with the standard therapy of high-dose progesterone.

In patients with intrauterine lumps that may be malignant, a pathological report should be obtained.

Core Tip: We report a rare case of atypical endometrial hyperplasia in a 35-year-old woman, who presented with a large mass in the uterus. Several characteristics were observed, including nulliparity, limited sexual activity in recent years, and irregular vaginal bleeding for 2 years. Gynecological examination revealed an enlarged uterus, and the uterine wall was relatively hard. Curettage was applied based on transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging results. The pathological examination findings were typical for atypical endometrial hyperplasia. The patient was cured after treatment with a high dose of progesterone. The findings from this case study will be valuable in clinical practice.

- Citation: Wu X, Luo J, Wu F, Li N, Tang AQ, Li A, Tang XL, Chen M. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia in a 35-year-old woman: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(31): 9629-9634

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i31/9629.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9629

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) is a common disorder in women, which leads to cancer in about 25% of cases[1,2]. Although 29% of cases can develop into endometrial carcinoma within 5 years if not treated in time due to the continuous effect of estrogen[1,3], the frequency and significance remain a subject of debate[4-11]. Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common tumor of the female genital tract in developed countries, ranking fourth in incidence among invasive tumors in women. It is estimated that 47130 new EC cases and 8010 EC deaths occurred in the United States in 2012[12].

Although 20%-25% of EC patients are diagnosed before menopause, 2%-14% of EC patients are younger women (< 40-years-old); thus, preservation of their fertility is required when a therapeutic plan is determined[13-16]. With increasing AEH diagnoses[17,18], AEH and EC patients are being diagnosed at younger ages, and up to 22%-66% of AEH patients are infertile. Here, we report a rare case of AEH in a 35-year-old patient, who was diagnosed according to the 2014 World Health Organization classification of tumors of female reproductive organs. This case study will be beneficial for gynecologists for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with AEH.

The aim of this study was to describe a rare case, in order to aid gynecologists in determining the appropriate management of abnormal uterine bleeding and intrauterine masses. If B-scan ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results suggest that the intrauterine masses may be malignant, a pathological report should be obtained to provide a basis for the next steps.

A 35-year-old woman presented to the Provincial Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital (Changsha, China) in March 2017 because of irregular vaginal bleeding for more than 1 year and presence of a lower abdominal mass for 4 mo.

The patient was nulliparous and overweight (body mass index = 28.1), with a 15-year history of primary infertility. Her age at menarche was 12-years-old, and the menstrual period lasted for 10 d. She got married at 20-years-old, and had been married for more than 15 years to date. Several characteristics were observed, including nulliparity, limited sexual activity (intercourse 1-2 times a year) in recent years, and irregular vaginal bleeding for 2 years without a pathological report. In April 2017, the patient found a palpable lower abdominal mass in the supine position, but there was no tenderness in the local area. By February 2018, the mass had increased in size, with the patient experiencing occasional lower abdominal pain and discomfort.

The patient denied a history of hepatitis, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and other infectious diseases, as well as chronic hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and other chronic diseases.

The patient was born in Guizhou Province, China. She did not have a history of smoking or drinking. Her occupation was housewife and the working conditions of such were general. She denied contact with toxic chemicals, poisons, or radioactive substances. She had married at the age of 20 and they were separated at the time of her case management. She reported her experience of sexual frequency in recent years as approximately every half year. She also reported not using contraception and never having been pregnant.

Findings from the gynecological examination revealed an enlarged uterus, similar to the uterus size in the fourth month of pregnancy, and the uterine wall was relatively hard.

Laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 7.7 × 109/L, neutrophils of 62.93%, hemoglobin level of 100 g/L, platelet count of 375 × 1012/L, and beta human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) level of 1.91 IU/L.

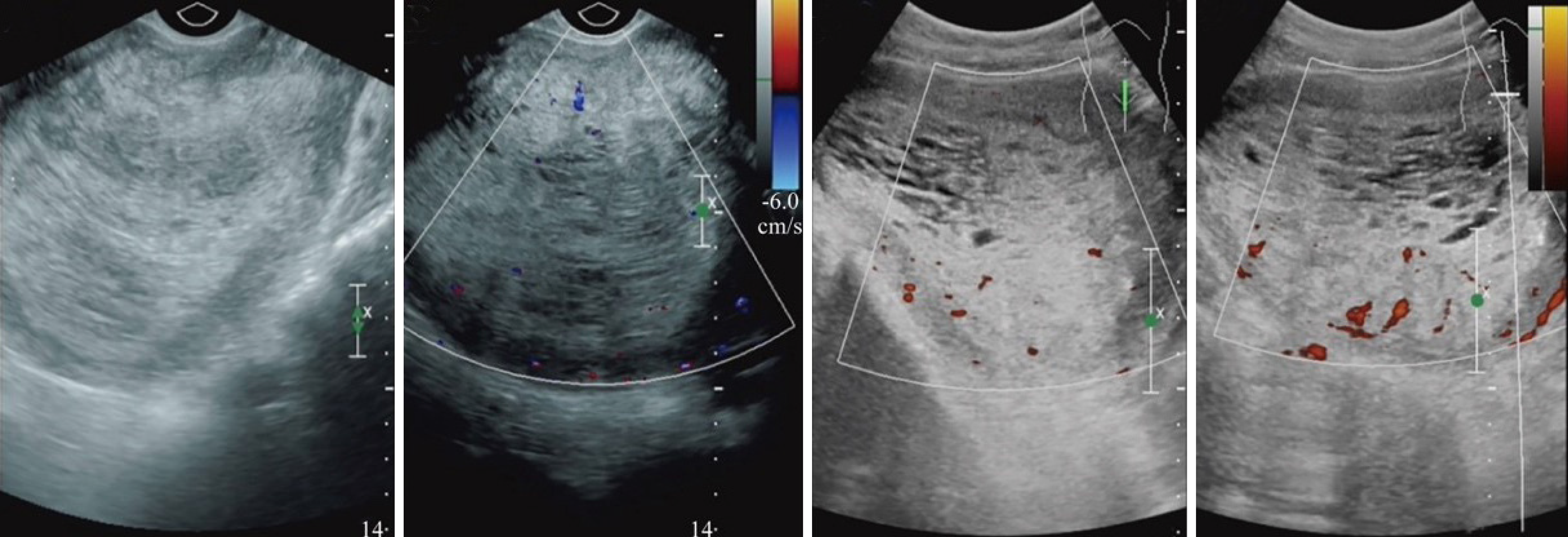

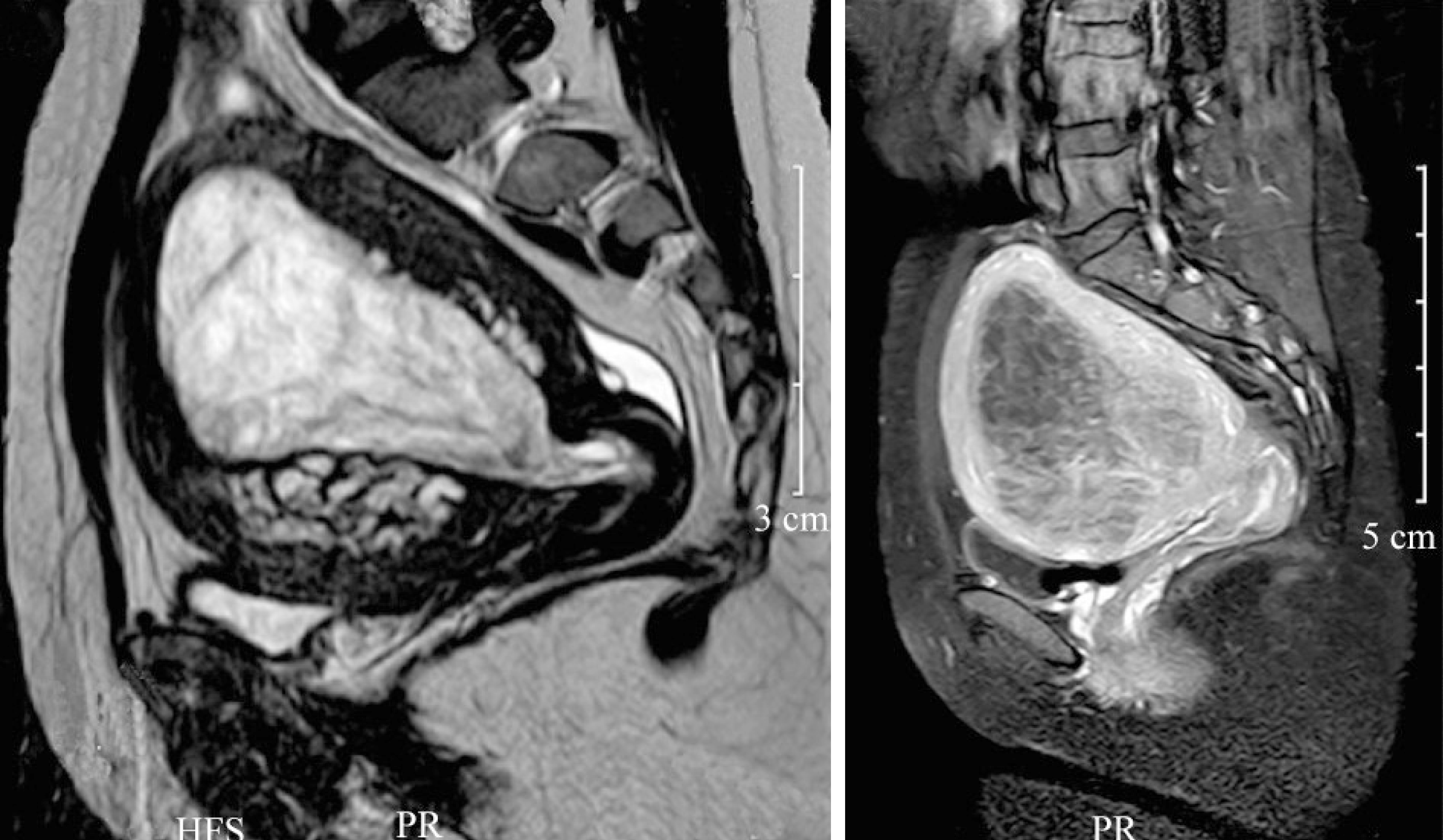

Transvaginal sonography (TVS) and MRI were performed to evaluate the intrauterine cavity. A lump of 10 cm in diameter with a partial honeycomb-like appearance was observed (Figure 1). MRI revealed abnormal signal focus and intensity in the intrauterine cavity. Considering the very large size of the abnormal signal (81 mm × 82 mm × 91 mm), the pathological finding was first classified as a hydatidiform mole (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with AEH.

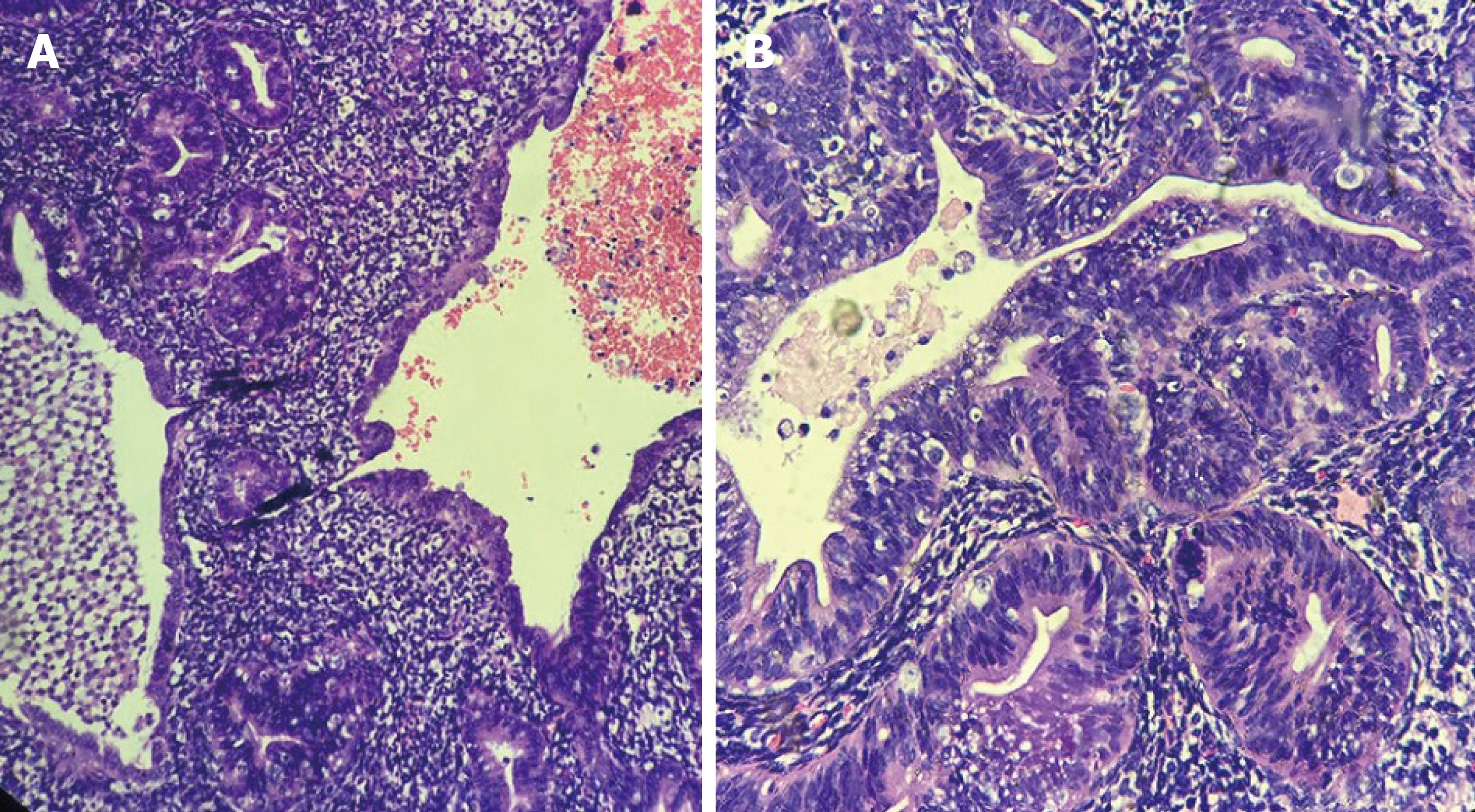

Curettage was performed based on the TVS and MRI results. However, the intrauterine tissue from the uterine curettage was extremely soft, and no typical phenotype of a hydatidiform mole was found. The tissue was collected for pathological examination. The results of hematoxylin and eosin staining showed an abnormal epithelial structure and inhomogeneous nuclei, which are typical characteristics of AEH (Figure 3). Based on the diagnosis of AEH, the patient was treated with high-dose progesterone for 3 mo.

After 3 mo, the patient was examined in the hospital of her hometown and told us that the AEH was cured.

This is an interesting case because the patient was at a reproductive age, and AEH is uncommon in this age group. Endometrial hyperplasia was identified as a precancerous pathological change. The intrauterine lump is commonly removed by surgery to decrease the risk of cancer, although the patient will no longer be able to become pregnant. To determine the therapeutic plan, physicians must balance the risk of cancer with the desire of the patient to become pregnant. In the current case, the patient accepted the traditional therapy without surgery even though a large mass was found. The prognosis of the patient was good without AEH recurrence or cancer, suggesting that the size of the lump is not critical in determining a therapeutic plan.

The MRI results showed that the intrauterine lump had a honeycomb-like appearance, which suggested the possibility of trophoblastic tumors, especially erosive hydatidiform moles. Trophoblastic tumors are often secondary to grape-sized moles, abortions, and other pregnancies[19,20]. However, the patient was nulliparous. Another key result from the blood test was a normal HCG level, which is the standard marker for diagnosing a hydatidiform mole. However, a placental site trophoblastic tumor could not be ruled out because most placental trophoblastic tumors are HCG-negative and the tumor manifests as a lump in the intrauterine cavity, which is confirmed by histological examination. Stromal sarcoma of the endometrium also could not be ruled out, as it occurs in women of reproductive age and can be characterized by irregular vaginal bleeding. In addition, tumors can grow in the uterine cavity in patients with a normal HCG level[21].

For young nulliparous patients who plan to become pregnant in the future, treatment with high-dose progesterone is recommended. However, in our patient, the size of the pathological tissue was larger than we have previously observed, as well as larger than masses reported by other physicians. The question remains of whether there are increased risks in AEH patients with large (compared to normal) size pathological tissue. We followed a typical therapeutic strategy by using a high dose of progesterone, and the patient was cured. In this case, we found that the size of the pathological tissue in AEH may not be the key element for determining the therapeutic plan. Rather, the results from pathological examination are required to determine a treatment plan.

In patients with irregular vaginal bleeding, including cases in which B-scan ultrasound and/or MRI indicate that the intrauterine lump may be malignant, an in-depth pathological report should be obtained to provide a basis for the next step. When the intrauterine mass is soft and it is estimated that uterine aspiration may clear the intrauterine focus, the uterus should not be removed for histological examination, especially in young nulliparous patients who want to retain their fertility. The size of the pathological mass may not increase the risk of cancer and can be treated with progesterone, similar to AEH patients with a normal sized pathological tissue.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Obstetrics and Gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gultekin M S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of "untreated" hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferenczy A, Gelfand M. The biologic significance of cytologic atypia in progestogen-treated endometrial hyperplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:126-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kalogera E, Dowdy SC, Bakkum-Gamez JN. Preserving fertility in young patients with endometrial cancer: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:691-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gusberg SB, Kaplan AL. Precursors of corpus cancer. IV. adenomatous hyperplasia as stage O carcinoma of the endometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1963;87:662-678. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Tavassoli F, Kraus FT. Endometrial lesions in uteri resected for atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;70:770-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kurman RJ, Norris HJ. Evaluation of criteria for distinguishing atypical endometrial hyperplasia from well-differentiated carcinoma. Cancer. 1982;49:2547-2559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Janicek MF, Rosenshein NB. Invasive endometrial cancer in uteri resected for atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:373-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Widra EA, Dunton CJ, McHugh M, Palazzo JP. Endometrial hyperplasia and the risk of carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1995;5:233-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dunton CJ, Baak JP, Palazzo JP, van Diest PJ, McHugh M, Widra EA. Use of computerized morphometric analyses of endometrial hyperplasias in the prediction of coexistent cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1518-1521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shutter J, Wright TC Jr. Prevalence of underlying adenocarcinoma in women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005;24:313-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ 2nd, Alberts D, Curtin J. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006;106:812-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in RCA: 8970] [Article Influence: 690.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jadoul P, Donnez J. Conservative treatment may be beneficial for young women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial adenocarcinoma. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:1315-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Le Digabel JF, Gariel C, Catala L, Dhainaut C, Madelenat P, Descamps P. [Young women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial adenocarcinoma stage I: will conservative treatment allow pregnancy? Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2006;34:27-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Benshushan A. Endometrial adenocarcinoma in young patients: evaluation and fertility-preserving treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;117:132-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ota T, Yoshida M, Kimura M, Kinoshita K. Clinicopathologic study of uterine endometrial carcinoma in young women aged 40 years and younger. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:657-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25541] [Article Influence: 1824.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 18. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7953] [Cited by in RCA: 8101] [Article Influence: 506.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Lewis JL Jr. Current status of treatment of gestational trophoblastic disease. Cancer. 1976;38:620-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bagshawe KD. Endocrinology and treatment of trophoblastic tumours. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol). 1976;10:140-144. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kim JA, Lee MS, Choi JS. Sonographic findings of uterine endometrial stromal sarcoma. Korean J Radiol. 2006;7:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |