Published online Nov 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9571

Peer-review started: March 27, 2021

First decision: June 3, 2021

Revised: June 18, 2021

Accepted: September 22, 2021

Article in press: September 22, 2021

Published online: November 6, 2021

Processing time: 215 Days and 16 Hours

Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN) is a rare condition that has been associated with low volume states, microvascular disease, gastrointestinal (GI) mucosal damage, and impaired GI motility. It has been linked in case reports with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and is commonly associated with GI bleeding (GIB).

We report a case of endoscopy confirmed AEN as a complication of DKA in a 63-year-old Caucasian male without any overt GIB and a chief complaint of epigastric pain. Interestingly, there was no apparent trigger for DKA other than a newly started ketogenic diet two days prior to symptom onset. A possible potentiating factor for AEN beyond DKA is the recent start of a Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA), though they have not been previously connected to DKA or AEN. The patient was subsequently treated with high dose proton pump inhibitors, GLP-1 RA was discontinued, and an insulin regimen was instituted. The patient’s symptoms improved over the course of several weeks following discharge and repeat endoscopy showed well healing esophageal mucosa.

This report highlights AEN in the absence of overt GIB, emphasizing the importance of early consideration of EGD.

Core Tip: Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN) is a rare condition with a mortality rate greater than 30%. It has been linked to low volume states including diabetic ketoacidosis in case reports but is usually associated with overt gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB). This report provides an important description of a patient presenting with AEN and no overt GIB. Interestingly, the apparent trigger for ketoacidosis appears to be a ketogenic diet. The case explores Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists as a possible AEN precipitant, which is not a finding previously described in the existing literature.

- Citation: Moss K, Mahmood T, Spaziani R. Acute esophageal necrosis as a complication of diabetic ketoacidosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(31): 9571-9576

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i31/9571.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9571

Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), also known as Black Esophagus or Gurvits Syndrome, is a rare entity distinguished by circumferential necrosis of the distal esophageal tissue that does not progress beyond the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ)[1]. The purported mechanisms of injury leading to AEN include ischemic injury, malnutrition, and acute gastric outlet obstruction or slowed peristalsis leading to increased gastric contents[2]. AEN has been linked with disease states that result in hemodynamic compromise, hypoperfusion, low volume states, and corrosive injuries[1]. One such possible disease state is diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a condition associated with hypoperfusion and transient hyperglycemic induced gastric dysmotility[3,4]. The treatment is high dose PPI, correction of causative condition, and monitoring for complications that may include esophageal strictures, perforations and abscess formation[2]. AEN is typically associated with gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB)[2], and only one[5] of the previous 13 reported cases, see Table 1 [5-15] of AEN in DKA did not present with overt GIB. We report a case of AEN as a complication of DKA in a patient without any overt GIB.

| Ref. | Presenting symptoms | GI bleeding | Age | Gender | Diabetes type 1 or 2 |

| Our case | Nausea, emesis, epigastric pain, dysphagia, odynophagea, anorexia | None | 63 | Male | 2 |

| Rigolon et al[5] | Nausea, emesis, epigastric pain, polyuria, polydipsia, fever | None | 50 | Male | 2 |

| Talebi-Bakhshayesh et al[6] | Altered mental status, abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, fatigue | Yes | 34 | Male | Unknown |

| Mccarthy et al[7] | Death | Unknown | 67 | Female | 2 |

| Uhlenhopp et al[8] | Encephalopathy, hypoxic respiratory failure | Yes | 56 | Male | 2 |

| Ghoneim et al[9] | Nausea, emesis, aphasia, gait difficulty | Yes | 67 | Female | Unknown |

| Ghoneim et al[9] | Nausea, emesis, right upper quadrant and epigastric abdominal pain | Yes | 78 | Female | 2 |

| Ghoneim et al[9] | Melena, malaise, chills, cough, anorexia | Yes | 35 | Male | 1 |

| Choksi et al[10] | Altered mental status | Yes | 65 | Male | Unknown |

| Vien and Yeung[11] | Lethargy, nausea, emesis, anorexia, odynophagia, | Yes | 37 | Female | 2 |

| Field et al[12] | Nausea, emesis, epigastric pain, anorexia | Yes | 37 | Female | 1 |

| Shah et al[13] | Melena, sepsis, fever, anorexia, syncope | Yes | 34 | Male | Unknown |

| Haghbeyan et al[14] | Emesis, anorexia | Yes | 55 | Female | Unknown |

| Buckshaw et al[15] | Nausea, emesis, epigastric pain | Yes | 50 | Male | 1 |

A 63-year-old retired Caucasian male presented to Emergency with severe epigastric pain and dysphagia and odynophagia to both solids and liquids leading to several days of anorexia. He also complained of nausea and non-bloody, non-bilious emesis. There was no evidence of overt GIB.

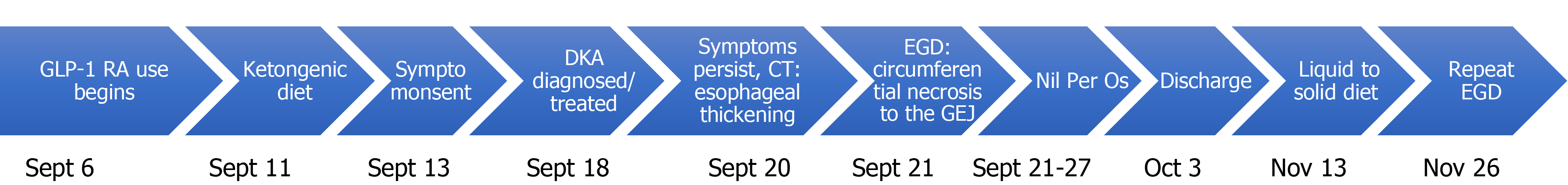

The patient noted that due to his hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) he was attempting to lose weight. To do this, his primary care provider switched him from his previous liraglutide which he had received for one year, to a trial of semaglutide one week prior to symptom onset. Additionally, he began a ketogenic diet to help with his weight loss goals and 2 d later, when performing manual labour, he became acutely unwell. He did not have a history of reflux disease or dysphagia prior to this episode and attempted to alleviate the discomfort with bed rest and ceasing oral intake. When the pain and nausea peaked 5 d following symptom onset, see Figure 1 for timeline, he presented to the hospital.

The patient had a several-year history of hypertension, dyslipidemia and T2DM with no known microvascular complications. His glycemic control had been poor with a most recent HbA1c of 8.4%. His medications included metformin 500 mg twice daily, ramipril 5 mg daily, ezetimibe 10 mg daily, duloxetine 60 mg daily, pravastatin 40 mg daily, and semaglutide 0.5 mg weekly.

The patient did not have any pertinent personal or family history. He did not have a significant alcohol intake, nor did he smoke or use recreational drugs.

The patient was 94 kg, 1.778 m tall, with a body mass index of 31.14 kg/m². Vital signs on presentation were notable for tachycardia (125 beats per minute), tachypnea (respiratory rate of 40) and blood pressure of 136/81. On physical exam he was noted to be in distress with Kussmaul respirations, lying in lateral decubitus position with voluntary abdominal guarding and frequent painful belching.

Admission blood work revealed hemoglobin of 165 g/L, leukocytes of 17.9 × 109 /L and an anion gap of 25 with bicarbonate of 5 mmol/L. Venous blood gas showed acidemia (pH = 7.02) and a B-hydroxybutyrate level of 10.2 mmol/L (normal < 0.25 mmol/L). His glucose was initially 17 mmol/L and peaked at 82 mmol/L. Urinalysis was negative for leukocytes or nitrites.

An abdominal CT ruled out bowel obstruction or intra-abdominal infection/abscess as the source of his discomfort but demonstrated circumferential wall thickening of the distal esophagus.

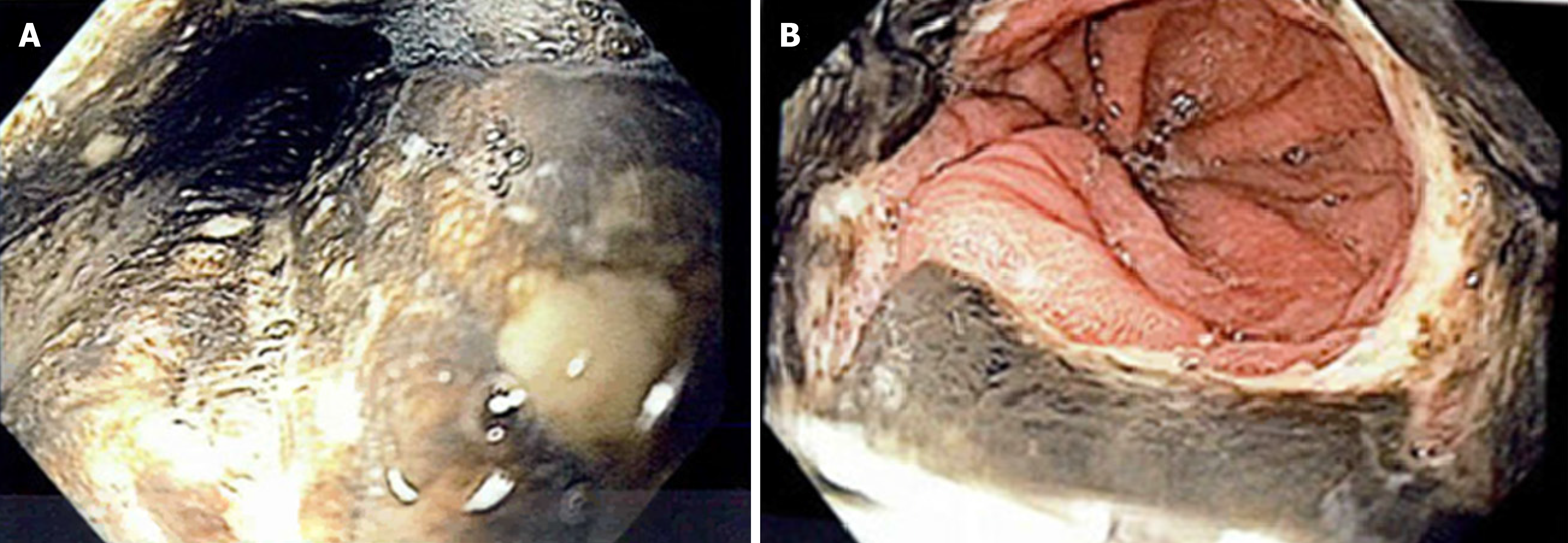

Following investigations, he was admitted to the hospital for first presentation DKA. No triggers were identified except perhaps his recently started ketogenic diet and dehydration. To rule out latent autoimmune diabetes in adults, C-peptides were ordered and were within normal limits, 1087pmol/L (normal 370-1470pmol/L). After the resolution of DKA, he continued to experience out of proportion epigastric pain, reflux symptoms, and dysphagia. To investigate, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed. This showed severe class D esophagitis involving the entire esophagus. There were circumferential black, necrotic inflammatory changes in the mid to distal esophagus that stopped abruptly at the GEJ. This was thought to represent AEN which can be seen in Figure 2. Biopsies were not taken of the necrotic tissue. Erosions were seen in the body and antrum of the stomach, and multiple clean based ulcers were seen in the duodenum. Biopsies were taken of the gastric and duodenal mucosa, and histology report showed chronic gastroduodenitis with no sign of H. pylori or infectious organisms as well as no evidence of neoplasia.

Following the EGD the patient was given pantoprazole 40 mg intravenously twice daily, sucralfate suspension of 1 g PO four times daily, and instructions to slowly increase from nil per os to clear and then full fluid diet.

He was discharged home in a stable condition on a liquid diet, sucralfate 2 g with meals and nightly for two weeks, and pantoprazole 40 mg twice daily. At discharge metformin and GLP-1 RA were discontinued and insulin aspart 5 units three times daily and insulin glargine 15 units nightly was prescribed.

A repeat EGD 8 wk post-discharge showed a healed esophagus with one polyp. Biopsies showed healed gastric and duodenal mucosa and mild inflammatory changes to the removed polyp. Follow up was arranged to ensure no return of symptoms and the patient's follow up HbA1c was improved from the previous 8.4 to 7.2.

DKA has been previously associated with AEN in several case reports: A rare complication of a common presentation. As mentioned earlier, 13 cases to date have been reported, most of which have been associated with GIB. In fact, AEN, in general, is associated with overt GIB in 88% of presentations, and also often associated with non-specific symptoms such as GI upset, dysphagia, and hypotension[2,16].

It is critical to recognize AEN as it is associated with a mortality of 32%[2]. This case highlights the importance of considering AEN despite a lack of GIB when other concerning features are present, such as dysphagia. AEN is especially important to consider in patients such as males over 60 or those with increased risk of microvascular disease or hemodynamic compromise[1,16,17].

Interestingly, our case highlights two triggers that may have led to DKA in this patient and put him at greater risk for AEN. First, ketogenic diets, especially in conjunction with other triggers like dehydration or physiologic stress, have been linked to ketoacidosis in multiple case reports in diabetic and non-diabetic patients[18-20]. Ketogenic diets deplete the body’s glucose reserve and shift the metabolism into ketogenesis primarily by hepatic oxidation of fatty acids, making ketones an alternative to glucose[18]. In a patient with type two diabetes mellitus, who already has insulin resistance, the body’s ability to regulate ketogenesis is reduced, making them more prone to ketoacidosis. Moreover, the introduction of GLP-1 RA increases lipolysis and ketogenesis[21]. The combination of these factors may have been sufficient to tip this patient into ketoacidosis.

After the development of DKA, the development of AEN is largely thought to be multifactorial. First, DKA is a low volume state that predisposes the esophagus to necrotic injury[22,23]. Second, the hyperglycemia in DKA decreases gastric motility which increases acid reflux to the esophagus and therefore renders the esophagus prone to injury[3,24]. Besides the direct impact of DKA, it is important to consider the risk factors associated with diabetes such as microvascular disease, which may have been underlying, which render the esophagus unable to withstand the hemodynamic changes associated with DKA. Furthermore, semaglutide is associated with adverse GI effects including gastritis, minor delays in gastric emptying, and GERD[23]. The delay in gastric emptying is caused by an inhibition of stomach peristalsis in combination with increased pylorus contraction[25]. A meta-analysis of adverse GI events in patients with T2DM using GLP-1 RAs showed that there is a dose-dependent increase in GI events, and GLP-1 RAs were more likely to cause adverse GI events in comparison to placebo[24] or insulin[25]. Severe GI adverse reactions occurred in 1.7% of patients at our patient’s newly started dose of 0.5 mg[23]. The GERD and gastroparesis associated with GLP-1 RA could cause caustic injury which is a known contributor to AEN.

In conclusion, this case reiterates the association between AEN and DKA. With the evolving era of medicine, where diet and oral hypoglycemics are combined, AEN in the context of DKA may become more prevalent given the various mechanisms of actions involved. This case serves as a reminder for clinicians to keep a low threshold to proceed with EGD even despite a lack of overt GIB.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Canada

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ray S, Shen HN S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3219-3225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:29-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Krishnasamy S, Abell TL. Diabetic Gastroparesis: Principles and Current Trends in Management. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:1-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ebert EC. Gastrointestinal complications of diabetes mellitus. Dis Mon. 2005;51:620-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rigolon R, Fossà I, Rodella L, Targher G. Black esophagus syndrome associated with diabetic ketoacidosis. World J Clin Cases. 2016;4:56-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Talebi-Bakhshayesh M, Samiee-Rad F, Zohrenia H, Zargar A. Acute Esophageal Necrosis: A Case of Black Esophagus with DKA. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18:384-385. [PubMed] |

| 7. | McCarthy S, Garland J, Hensby-Bennett S, Philcox W, Kesha K, Stables S, Tse R. Black Esophagus (Acute Necrotizing Esophagitis) and Wischnewsky Lesions in a Death From Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Possible Underlying Mechanism. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2019;40:192-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Uhlenhopp DJ, Pagnotta G, Sunkara T. Acute esophageal necrosis: A rare case of upper gastrointestinal bleeding from diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Pract. 2020;10:1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ghoneim S, Shah A, Dalal S, Landsman M, Kyprianou A. Black Esophagus in the Setting of Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Rare Finding from Our Institution. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2019;13:475-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Choksi V, Dave K, Cantave R, Shaharyar S, Joseph J, Shankar U, Kaplan S, Feiz H. "Black Esophagus" or Gurvits Syndrome: A Rare Complication of Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2017;2017. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vien LP, Yeung HM. Acute Esophageal Necrosis (Gurvits Syndrome): A Rare Complication of Diabetic Ketoacidosis in a Critically Ill Patient. Case Rep Med. 2020;2020:5795847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Field Z, Kropf J, Lytle M, Castaneira G, Madruga M, Carlan SJ. Black Esophagus: A Rare Case of Acute Esophageal Necrosis Induced by Diabetic Ketoacidosis in a Young Adult Female. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2018;2018:7363406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shah AR, Landsman M, Waghray N. A Dire Presentation of Diabetic Ketoacidosis with "Black Esophagus. Cureus. 2019;11: e4761. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Haghbayan H, Sarker AK, Coomes EA. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis complicating diabetic ketoacidosis. CMAJ. 2018;190:E1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Buckshaw R, Stern ES, Andrews R, Stelzer F. Esophageal Necrosis: A Rare Complication of Diabetic Ketoacidosis – A Case Report. Poster Presented at: The American College of Physicians- Nationals, Philadelphia, PA. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gurvits GE, Cherian K, Shami MN, Korabathina R, El-Nader EM, Rayapudi K, Gandolfo FJ, Alshumrany M, Patel H, Chowdhury DN, Tsiakos A. Black esophagus: new insights and multicenter international experience in 2014. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:444-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Day A, Sayegh M. Acute oesophageal necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg. 2010;8:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | White-Cotsmire AJ, Healy AM. Ketogenic Diet as a Trigger for Diabetic Ketoacidosis in a Misdiagnosis of Diabetes: A Case Report. Clin Diabetes. 2020;38:318-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | von Geijer L, Ekelund M. Ketoacidosis associated with low-carbohydrate diet in a non-diabetic lactating woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | MacDonald PE, El-Kholy W, Riedel MJ, Salapatek AM, Light PE, Wheeler MB. The multiple actions of GLP-1 on the process of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2002;51 Suppl 3:S434-S442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nakatani Y, Maeda M, Matsumura M, Shimizu R, Banba N, Aso Y, Yasu T, Harasawa H. Effect of GLP-1 receptor agonist on gastrointestinal tract motility and residue rates as evaluated by capsule endoscopy. Diabetes Metab. 2017;43:430-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Burtally A, Gregoire P. Acute esophageal necrosis and low-flow state. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:245-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Novo Nordisk Canada. Product Monograph Ozempic [Internet]. Mississauga, 2020. [cited 2020 December 21]. Available from: https://www.novonordisk.ca/content/dam/Canada/AFFILIATE/www-novonordisk-ca/OurProducts/PDF/ozempic-product-monograph.pdf. |

| 24. | Blanco JC, Khatri A, Kifayat A, Cho R, Aronow WS. Starvation Ketoacidosis due to the Ketogenic Diet and Prolonged Fasting - A Possibly Dangerous Diet Trend. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:1728-1731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li WX, Gou JF, Tian JH, Yan X, Yang L. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists versus insulin glargine for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2010;71:211-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |