Published online Jan 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.736

Peer-review started: October 15, 2020

First decision: October 27, 2020

Revised: November 11, 2020

Accepted: November 29, 2020

Article in press: November 29, 2020

Published online: January 26, 2021

Processing time: 97 Days and 9.4 Hours

Choledocholithiasis removal via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) then followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has gradually become the principal method in the treatment of gallstones and choledocholithiasis. We use ERCP through the cystic duct to treat gallstones combined with choledocholithiasis, with the aim to preserve the normal function of the gallbladder while simultaneously decreasing risk of biliary tract injury.

A total of six cases of patients diagnosed with gallstones and choledocholithiasis were treated with ERCP. The efficacy was evaluated via operation success rate, calculus removal rate, postoperative hospital stay and average hospitalization costs; the safety was evaluated through perioperative complication probability, gallbladder function detection and gallstones recrudesce. The calculus removal rate reached 100%, and patients had mild adverse events, including 1 case of postoperative acute cholecystitis and another of increased blood urinary amylase; both were relieved after corresponding treatment, the remaining cases had no complications. The average hospital stay and hospitalization costs were 6.16 ± 1.47 d and 5194 ± 696 dollars. The 3-11 mo follow-up revealed that gallbladder contracted well, without recurrence of gallstones.

This is the first batch of case reports for the treatment of gallstones and choledocholithiasis through ERCP approached by natural cavity. The results and effects of six reported cases proved that the new strategy is safe and feasible and is worthy of further exploration and application.

Core Tip: Radical treatment for gallbladder stones and choledocholithiasis through natural cavity endoscopy is one of the technical innovation surgeons have worked hard to explore. We report six cases of gallbladder stones combined with choledocholithiasis treated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography through the cystic duct. The stones were completely removed, and the 11 mo follow-up showed gallbladder function remains intact. This strategy successfully decreased risk for secondary operations and cholecystectomy, was minimally invasive, preserved the integrity of gallbladder and common bile duct and should be regarded as a true natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery operation.

- Citation: He YG, Gao MF, Li J, Peng XH, Tang YC, Huang XB, Li YM. Cystic duct dilation through endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for treatment of gallstones and choledocholithiasis: Six case reports and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(3): 736-747

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i3/736.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.736

Gallstones with choledocholithiasis represents one of the most common clinical diseases[1-3]. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the standard procedure for benign gallbladder diseases[4]; endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is one of the first choices for the treatment of choledocholithiasis[5-7]. Cholecystectomy with open choledochotomy, LC after endoscopic calculus removal, or LC combined with laparoscopic common bile duct exploration is currently the common treatment for patients with gallstones and choledocholithiasis[8-10]. However, transabdominal cholecystectomy may have complications such as abdominal pain, incisional hernia, abdominal adhesions or incision infections[11]. Therefore, to promote postoperative recovery, it is important to identify a technology for treating gallstones and choledocholithiasis with few scars or no scars and limited trauma, pain and interference of immune and physiological functions[12]. Recently, it was reported in the literature that ERCP combined with the SpyGlass system was used to insert a metal or plastic stent via the common bile duct, followed by gallstone removal after the stent dilation in the second phase. The patient recovered well after surgery without serious complications[13]. The operation solved the issues of gallstones and choledocholithiasis in one procedure via the natural cavity under endoscopy, while requiring no conventional surgery, providing a new idea for treating such diseases. However, this surgical method not only requires a second-phase operation, implanting a metal or plastic stent, but also has a higher hospitalization cost and longer hospital stay. Therefore, we asked if there are methods for treating gallstones and choledocholithiasis via the natural cavity under endoscopy with one procedure rather than conventional surgery? We removed gallstones via the natural cavity and choledocholithiasis via the dilated cystic duct in one procedure through ERCP while preserving the gallbladder function. The procedure is now reported as follows, and we discuss its safety and feasibility.

Six patients included 3 males and 3 females aged 28 to 66 years diagnosed with gallstones and choledocholithiasis in the Department of Hepatobiliary, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Army Medical University. Everyone complained of upper abdominal pain, nausea and fatigue.

The characteristics of the six patients are shown in Table 1: Three males and three females aged 18-66 years. The number of gallstones was 1-3, the diameter of the gallstones was 4-13 mm and the thickness of the gallbladder wall was 3-6 mm. The number of choledocholithiases was 1-16, the diameter of choledocholithiasis was 5-13 mm, and the diameter of the choledocholithiases was 10-17 mm.

| Case No. | ALT, IU/L | AST, IU/L | TBIL, μmol/L | DBIL, μmol/L | Hb, g/L | WBC, 109/L | PT, s | History of past illness |

| 1 | 17.3 | 18 | 22.3 | 6.8 | 148 | 5.43 | 11.9 | Hypertension |

| 2 | 1025.4 | 594.9 | 92.4 | 63.7 | 140 | 8.24 | 10.9 | Normal |

| 3 | 129.6 | 72.6 | 12.9 | 2.8 | 129 | 4.18 | 10.8 | Normal |

| 4 | 115.8 | 58.7 | 35.3 | 10.8 | 151 | 5.08 | 10.2 | Right upper lung lobectomy |

| 5 | 184.1 | 71.9 | 13.6 | 3.4 | 129 | 4.65 | 10.8 | Normal |

| 6 | 28.4 | 21.8 | 12.6 | 2 | 135 | 8.89 | 11.6 | Duodenectomy and anastomosis |

Case 1 had a history of hypertension and received oral amlodipine of 5 mg to control blood pressure; Case 5 had a history of right upper lung lobectomy; Case 6 had duodenal tumor in 2003 and was treated with left inguinal hernia repair in 2016. Other patients had no special illness history (Table 1).

All the patients had soft abdomen, the right upper abdomen was tender and no rebound pain. Among them, Case 2 and Case 5 simultaneously presented with yellowish skin and sclera, accompanied by yellow urine.

Cases 2, 3, 4 and 5 had abnormal liver functions with increased aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase; the other 2 patients had normal laboratory examinations, see in Table 1.

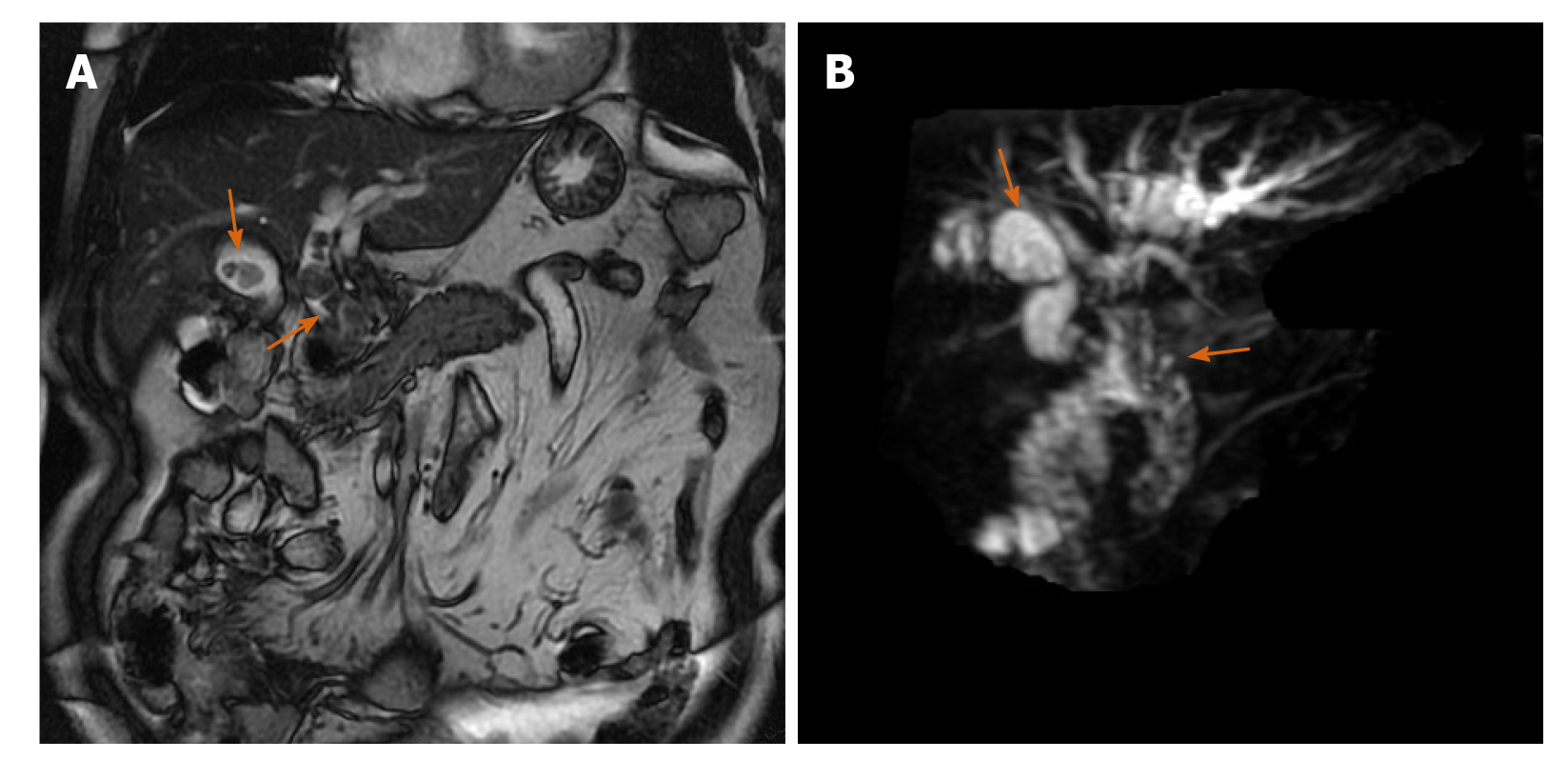

Before the operation, the patients were examined by abdominal ultrasound, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or abdominal computed tomography (Figure 1A).

The examinations and imaging findings were concerning for gallstones and choledocholithiasis.

All cases were examined with a Fuji duodenoscope (FUJINON, EPX-4400 endoscopic system, ED-530XT lens, Tokyo, Japan); an ERCP related device and consumables as the operation required; a guide wire (COOK, METII-21-480 or ACRO-25-480, Bloomington, IN, United States); needle knife papillotomes (COOK, DASH-1 or DASH-35); a dilatation balloon (COOK, QBD-8 × 3 or QBD-10 × 3); a basket for calculus removal (MWB-2×4 or MWB-3×6; FS-LXB-2 × 4 or FS-LXB-3 × 6); a balloon for calculus removal (COOK TXR-8.5-12-15-A); and a nasal biliary drainage catheter (COOK, ENBD-7- LIGUORY 7F, COOK ENBD-7-NAG 7F).

The diameter of the cystic duct should be measured preoperatively with MRCP. The gallstone can be removed directly without dilating the cystic duct if the diameter of the cystic duct is larger than that of the gallstone; if the diameter of the gallstone is larger than that of the cystic duct, it is necessary to use a balloon to expand the cystic duct to between 1.1 and 1.3 times the diameter of it. This therapy strategy should be abandoned if the gallstone is still larger than the dilated cystic duct.

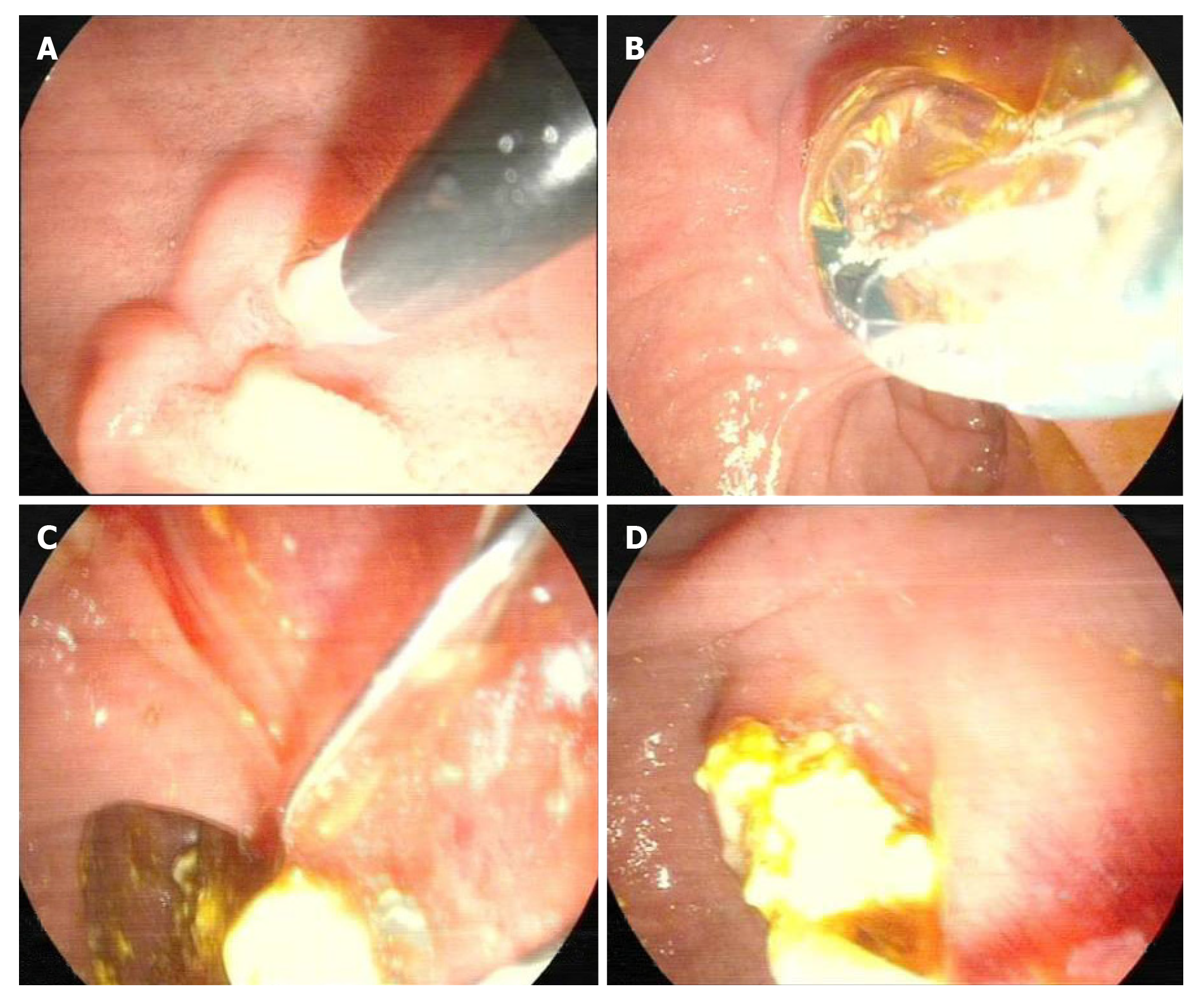

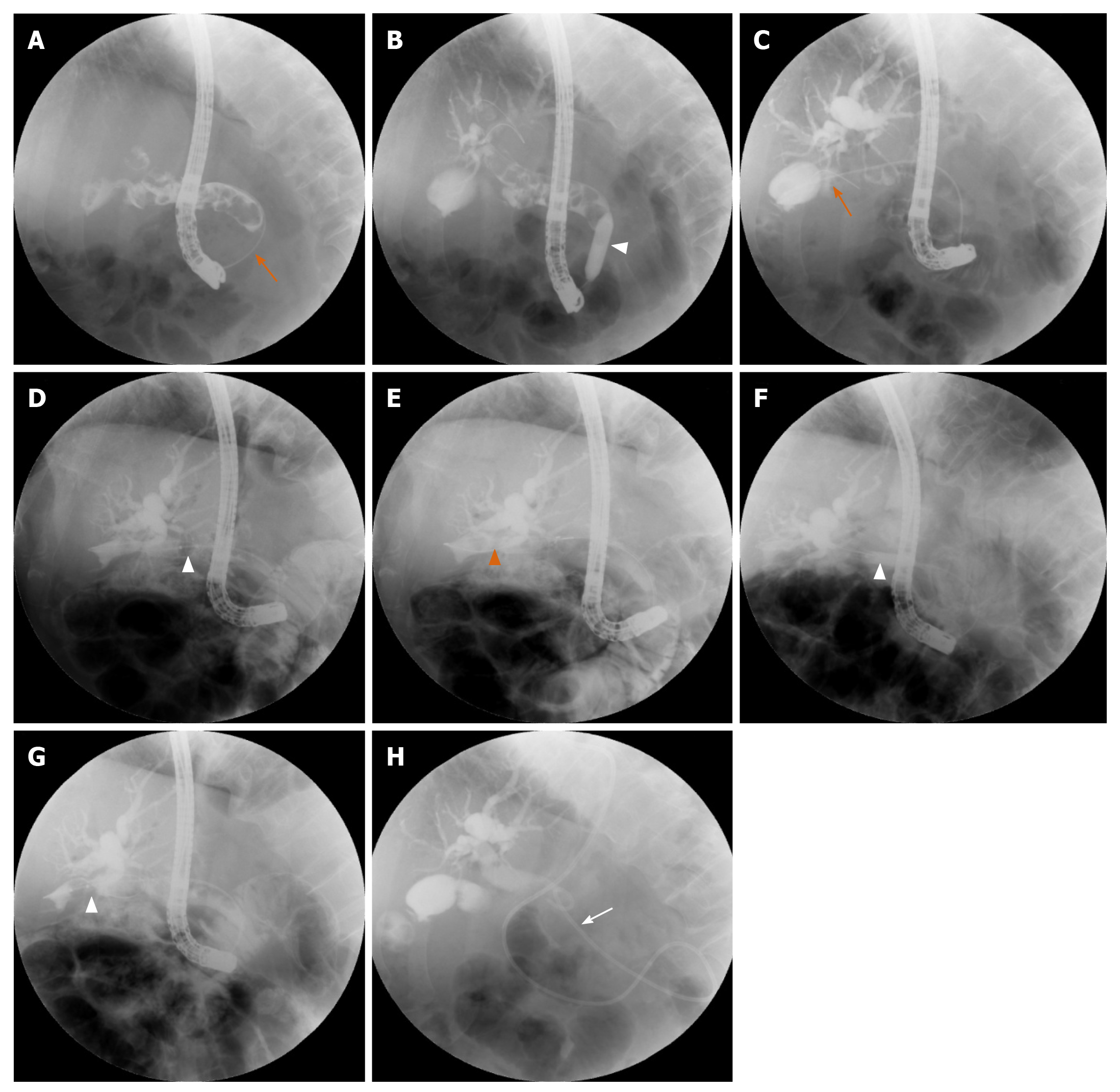

Routine MRCP was performed for the initial evaluation before the operation to identify gallstones and choledocholithiasis (Figure 1B). Patients with calculus diameters less than 0.8 cm and diameter of cystic duct greater than 0.5 cm were selected. In the conventional ERCP position, the duodenum and papilla were observed under the microscope, and cholangiography was performed after successful papilla intubation with the bow knife guided by the guide wire. The lower part of the common bile duct was dilated with a dilation balloon, the choledocholithiasis was removed with a basket for calculus removal and a basket for calculus crush and the residual calculus was checked for the extrahepatic bile duct (Figures 2A and 3A). The guide wire arch knife was used for super selection of the cystic duct, and cholecystography was performed. Then, whether cystic duct balloon dilatation was performed was decided based on the diameters of the cystic duct and gallstones. Patients who met the criteria first underwent fluoroscopic cylindrical balloon dilation, and the diameter after dilation was greater than 0.8 cm. Next, the basket for calculus removal or balloon was inserted into the gallbladder via the cystic duct to remove the gallstones (Figures 2B-D and 3C-E). Then, the nasal biliary drainage catheter was inserted after confirming thorough removal of the gallstones and choledocholithiasis (Figure 3F). Rehydration, anti-infection and nutrition as well as other conventional treatments were given after the operation. Transnasal cholangiography was performed on the first day after the operation to check for residual calculus, and the nasal biliary drainage catheter was pulled out when no calculus remained in the gallbladder or common bile duct. Therefore, all patients took ursodeoxycholic acid after the operation to reduce the recurrence of calculus[14].

(1) The achievement ratio of calculus removal was measured. (2) The operation time and dilation of the cystic duct were recorded. (3) The postoperative diet recovery time, length of hospital stay and hospitalization costs were measured. (4) Complications were recorded; the Clavien-Dindo Complication Grading System was used for rating the operative complications.

The specific formula was as follows: Gallbladder excretion function (%) = (fasting gallbladder volume - postprandial gallbladder volume)/(fasting gallbladder volume) × 100%, [GBEF (%) = (FGBV - PGBV)/(FGBV) × 100%][15].

All patients were re-examined by: (1) Abdominal ultrasound every month after the operation; (2) MRCP re-examination was performed 3 mo after the operation; and (3) The contraction function of the gallbladder was examined 3, 6, 9 and 12 mo after the operation. Gallbladder function was measured by the GBEF value, FGBV and PGBV 30 min after a fatty meal.

All patients had successful operations with complete calculus removal. One patient underwent postoperative nasal cholangiography and was found to have residual calculus in the gallbladder and common bile duct, so ERCP was performed again for calculus removal. According to the examination, the cystic duct in all patients was smooth without distortion or stenosis. The efficacy was evaluated through the achievement ratio of the operation, removal rate of calculus, postoperative hospital stay and average hospitalization costs; safety was evaluated through the perioperative complication probability, postoperative detection of gallbladder function and recurrence of gallstones (Table 2). The patients had mild postoperative adverse events, including 1 patient who received secondary ERCP and had acute cholecystitis after the operation, which improved after anti-infection treatment was provided. One patient had increased blood urinary amylase, which improved after treatment with inhibitory enzymes and nutrition was provided. The remaining patients had no complications, such as hemorrhage, cholangitis, pancreatitis or duodenal perforation. The abovementioned complications were rated as level II by the Clavien-Dindo grading system, thus not requiring additional surgical procedures.

| No. | Follow-up period in mo | Residual stones | GBEF before surgery, % | GBEF after surgery, % | Biliary colic | Calculus recurrence | ||

| 3 mo | 6 mo | 9 mo | ||||||

| 1 | 11 | No | 53 | 95 | 82 | 83 | No | No |

| 2 | 6 | No | 60 | 73 | 80 | NA | No | No |

| 3 | 8 | No | 55 | 60 | NA | NA | No | No |

| 4 | 6 | No | NA | 52 | NA | NA | No | No |

| 5 | 6 | No | 54 | 62 | 68 | NA | No | No |

| 6 | 8 | No | NA | 56 | 72 | NA | No | No |

All six patients had successful operations with complete calculus removal. The time of ERCP was 95-140 min. All patients were treated with a nasal biliary catheter for drainage after the operation, and the nasal biliary catheter was inserted into the extrahepatic bile duct (Table 3). One patient underwent transnasal cholangiography after the first calculus removal, which showed residual calculus in the gallbladder and common bile duct, so ERCP was performed again (Table 4).

| No. | Gender | Age in yr | Number of gallstones | Diameter of gallstones, mm | Thickness of gallbladder wall, mm | Cystic duct diameter, mm | Cystic duct length, mm | Cystic duct direction | Number of choledocholithiasis | Diameter of common bile duct, mm | Diameter of choledocholithiasis, mm | Dilating the cystic duct | |||

| 1 | Male | 66 | 3 | 13 | 5.6 | 6 | 2.9 | Right | 16 | 13 | 13 | Yes | |||

| 2 | Female | 28 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 3.5 | Right | 6 | 16.3 | 6 | No | |||

| 3 | Female | 31 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 2.5 | Right | 4 | 15 | 5 | Yes | |||

| 4 | Male | 43 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | Dorsal | 3 | 12 | 5 | No | |||

| 5 | Female | 41 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 3 | Right | 1 | 10 | 7 | No | |||

| 6 | Male | 59 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2.7 | Dorsal | 2 | 11 | 9 | Yes | |||

| No. | ERCP operation time, min | EPBD, cm | Biliary stent | ENBD | Secondary ERCP |

| 1 | 140 | 0.8 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | 120 | 0.6 | No | Yes | No |

| 3 | 125 | 0.8 | No | Yes | No |

| 4 | 95 | 0.6 | No | Yes | No |

| 5 | 105 | 0.6 | No | Yes | No |

| 6 | 110 | 0.8 | No | Yes | No |

Biliary colic in all patients was gradually relieved after the operation. As shown in Table 4, the patients had mild postoperative adverse events, including 1 patient who received secondary ERCP due to residual calculus in the gallbladder and common bile duct, as shown by transnasal cholangiography, and who had acute cholecystitis after the operation, which improved after anti-infection treatment was provided. One patient had increased blood urinary amylase, which improved after treatment with inhibitory enzymes and nutrition was provided. The remaining patients had no complications, such as hemorrhage, cholangitis, pancreatitis or duodenal perforation. The abovementioned complications were rated as level II by the Clavien-Dindo grading system, thus not requiring additional surgical procedures (Table 5).

| No. | Hyperamylasemia | Cholecystitis | Hemorrhage | Cholangitis | Cystic duct injury | Duodenal injury |

| 1 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| 2 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 3 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 4 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 5 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 6 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

For patients with gallstones and choledocholithiasis treated by cystic duct dilatation through ERCP in our department from January 2019 to January 2020, the average length of hospital stay was 6.16 ± 1.47 d (n = 6), and the hospitalization cost was 5194 ± 696 dollars (n = 6). For patients treated by laparoscopic common bile duct incision for calculus removal and cholecystectomy in the same period, the average length of hospital stay was 12.73 ± 3.17 d (n = 11), and the hospitalization cost was 6619 ± 1466 dollars (n = 11). For patients treated by LC after ERCP, the average length of hospital stay was 9.90 ± 2.78 d (n = 20), and the hospitalization cost was 6606 ± 2605 dollars (n = 20). In the treatment of gallstones and choledocholithiasis by cystic duct dilatation through ERCP, most of the costs were for special materials such as guide wires, endoscopic papillary balloon dilation and endoscopic nasobiliary drainage.

The current methods for the treatment of gallstones and choledocholithiasis areas[6,16] are follows: (1) Cholecystectomy + common bile duct exploration: This is a classic standard practice, with relatively low technical requirements, a short operation time, a high achievement ratio of the operation and easy promotion; however, it also has disadvantages such as substantial trauma, high requirements for cardiopulmonary function, a long time to resume the diet, a slow recovery of gastrointestinal tract function, a high probability of postoperative incision infection, a long hospital stay and affected quality of life by the postoperative indwelling T tube; (2) LC + common bile duct exploration: This surgical method is completed under laparoscopy on the basis of laparotomy. Compared with the former, it is less invasive and has a faster recovery; however, it still requires a T tube to be retained after the operation, which affects the quality of life; and (3) Common bile duct calculus removal through ERCP + LC: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the gold-standard surgical procedure for treating benign gallbladder diseases[17], with less trauma, a shorter hospital stay, less pain and a faster postoperative recovery. However there are cholecystectomy-related surgical risks, including bile duct injury, hemorrhage, bile fistula, abdominal infection and duodenal perforation as well as probable occurrence of chronic diarrhea and malignant tumors of the digestive system (colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, esophageal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma) after the operation due to cholecystectomy and loss of gallbladder function[6,18,19]. In our cases, gallbladder stones combined with recent secondary choledocholithiasis were treated with ERCP, which decreased likelihood of cholecystectomy and related risks while retaining gallbladder and its function, expanding the benefits of patients. In addition, the occurrence of postoperative complications during the entire minimally invasive surgery is similar to that of conventional ERCP. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to find new treatment strategies to further reduce the corresponding trauma and surgical scars.

New treatment strategies, including natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) cholecystectomy via the stomach, vagina and colorectum have been explored[20,21]. This method has obvious advantages over LC, such as a more satisfactory appearance, less systemic inflammation, mild postoperative pain, a faster recovery and the avoidance of incisional hernia[22]; however, NOTES also has many problems that need to be solved, including the surgical approach via the abdominal cavity, the prevention of interference, suture and anastomosis instruments, the spatial positioning method, the incision closure technique, personnel training and the surgical operation platform, among which, the surgical approach and incision closure technique are the most important[23]. In addition, transvaginal cholecystectomy is limited to female patients and requires the assistance of laparoscopic instruments, so it requires the collaboration of gynecologists and surgeons[24-26].Therefore, after the approval of the ethics committee, we selected suitable patients (recent occurrence of secondary choledocholithiasis, with the largest diameter of gallstones less than 0.8 cm or less than the inner diameter of the dilated cystic duct), performed complete choledocholithiasis removal, and then established a natural channel for the common bile duct–cystic duct for calculus removal to dilate the gallbladder via the cystic duct with the cystic duct dilation technique. After completely removing the gallstones, the calculus in the common bile duct was removed to perform concurrent treatment for gallstones and choledocholithiasis. This surgical treatment method is completely different from the previous treatment concept. The entire surgical procedure and postoperative treatment are the same as conventional ERCP. According to preliminary clinical studies, patients recovered well after the operation without related complications. This method is expected to become an effective treatment strategy that is completely different from the current strategies.

The advantages of trans-cystic duct ERCP in the treatment of gallstones and choledocholithiasis are as follows: (1) The entire surgical procedure is completed under duodenoscopy, and no cholecystectomy is required; (2) The treatment results in a shorter hospital stay and low hospitalization costs, there are no surgery-related scars or complications and gallbladder function is retained. Compared with the report by Liu et al[13], this technique is a one-step treatment for gallstones and choledocholithiasis and does not use metal stents to avoid a second application of the SpyGlass system, which greatly reduces the hospitalization costs; (3) There is a decreased incidence of complications, and there is no occurrence of complications such as biliary tract injuries because no cholecystectomy is required; (4) It is performed via natural channels without damage to the gallbladder mucosa and with maintenance of normal gallbladder function. The patient's normal physiological anatomy is basically restored after the operation, which improves the patient's quality of life and is more acceptable to patients; and (5) The occurrence of some gallstones is correlated with the inadequate bile drainage caused by a twisted cystic duct. By dilating the cystic duct, the aforementioned drainage problems are corrected, accordingly restoring the normal physiology and reducing the recurrence of calculus.

From our current experience, this technology still has certain disadvantages: (1) It is only effective for some patients. It is expected to be successful for those with 1 or less than 10 calculi, where the diameter of the gallstones is less than 0.8 cm, or in cases where although the diameter of the cystic duct is greater than 0.8 cm, the diameter of the cystic duct is dilated at the same time, and the diameter of calculus is less than 3 mm. Patients who meet the aforementioned criteria may easily achieve success. However, we believe that with the improvement of experience, the criteria for patients suitable for this operation will become increasingly wider. (2) ERCP is one of the preferred therapies for choledocholithiasis. It has been reported that some complications including recurrent cholangitis, pancreatitis, hemorrhage and perforation occurred after the endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST)[27,28]. There also occurred complications in our preliminary practice 20 years ago. However, the aforementioned complications occurring rate has been reduced significantly after the reported studying curve (180-200 cases)[29,30]. In our center, ERCP plus EST is safe and effective for the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Arguably, ERCP is quite safe for surgeons with rich experience. However, it is not suitable for inexperienced surgeons (operating less than 200 cases totally or less than 100 cases annually). Thus, this operation strategy is suggested to be selectively developed in a large and experienced medical center. The key to the entire process is inserting the guide wire or balloon into the gallbladder. If insertion cannot be achieved, the entire surgical process cannot be continued. The surgeon should move gently and slowly during the operation, and brute force is not allowed. The procedure should be abandoned if success is not achieved in 10 attempts.

Guide wire insertion into the gallbladder is the key to the success of operation. First of all, the selective cystic duct intubation strategy should be applied based on the site and direction of the cystic duct incision. Before the operation, operators should read the MRCP image carefully and know about the site, shape, direction and length of the cystic duct incision. We have found that the gallstones might cause significant dilation of the cystic duct during the process of removing from the cystic duct, and the dilation diameter usually ranged from 0.3 cm to 0.8 cm; therefore, the difficulty of the guide wire entering the gallbladder was substantially reduced. Although the location of the cystic duct joining the common bile duct may increase the difficulty, it can be solved by adjusting the entry direction of the guide wire. Among them, entering from the left side is the most difficult, while entering from the right side is relatively easier. For those patients with twisted cystic duct, the difficulty of the guide wire entering into the gallbladder is reduced after dilation by gallstone removal. Secondly, we also noticed that the different location of gallstones needs variable management methods. We select those patients with recent secondary choledocholithiasis and with countable gallstones to perform transcystic duct exploration. For the convenience of gallstone removal, an appropriate amount of bile should be sucked to narrow the gallbladder before the operation. Either a mesh basket or a balloon can be used for the exploration depending on the location of the gallstone in the gallbladder. When the gallstone is located in the body of gallbladder, the mesh basket will be preferred; while if the gallstone is located in the neck or the ampulla of gallbladder, the balloon can be used to push it to the body of gallbladder or pull the gallstone out directly.

In summary, in select cases, we propose the use of a new endoscopic treatment method for removal of gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones through the natural cavity at one time. This strategy decreased risk of secondary operations and cholecystectomy and was minimally invasive while retaining the integrity of the gallbladder and common bile duct. It is a true NOTES operation. The advantages of this completely new strategy include decreased cost and low trauma, which contributed to quick recovery and shortened hospital stay. Moreover, it is technically safe and feasible with great application value, and it can be practiced in some endoscopy centers with relevant experience. With an accumulation in the number of cases, an increasing number of people will be able to benefit from this procedure.

We sincerely thank Zheng L for his assistance and contribution in completing this work.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Saito H S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O'Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg. 2004;239:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lyu Y, Cheng Y, Li T, Cheng B, Jin X. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration plus cholecystectomy versus endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography plus laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholecystocholedocholithiasis: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:3275-3286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Prasson P, Bai X, Zhang Q, Liang T. One-stage laproendoscopic procedure versus two-stage procedure in the management for gallstone disease and biliary duct calculi: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3582-3590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bansal VK, Misra MC, Rajan K, Kilambi R, Kumar S, Krishna A, Kumar A, Pandav CS, Subramaniam R, Arora MK, Garg PK. Single-stage laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and cholecystectomy versus two-stage endoscopic stone extraction followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:875-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fitzgibbons RJ Jr, Gardner GC. Laparoscopic surgery and the common bile duct. World J Surg. 2001;25:1317-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Darrien JH, Connor K, Janeczko A, Casey JJ, Paterson-Brown S. The Surgical Management of Concomitant Gallbladder and Common Bile Duct Stones. HPB Surg. 2015;2015:165068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Parra-Membrives P, Díaz-Gómez D, Vilegas-Portero R, Molina-Linde M, Gómez-Bujedo L, Lacalle-Remigio JR. Appropriate management of common bile duct stones: a RAND Corporation/UCLA Appropriateness Method statistical analysis. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1187-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li MK, Tang CN, Lai EC. Managing concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones in the laparoscopic era: a systematic review. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2011;4:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Horn JK, Siperstein AE, Schecter WP, Campbell AR, Mackersie RC, Rodas A, Kreuwel HT, Harris HW. Prospective randomized trial of LC+LCBDE vs ERCP/S+LC for common bile duct stone disease. Arch Surg. 2010;145:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Dasari BV, Tan CJ, Gurusamy KS, Martin DJ, Kirk G, McKie L, Diamond T, Taylor MA. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD003327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McGee MF, Rosen MJ, Marks J, Onders RP, Chak A, Faulx A, Chen VK, Ponsky J. A primer on natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery: building a new paradigm. Surg Innov. 2006;13:86-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wagh MS, Thompson CC. Surgery insight: natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery--an analysis of work to date. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:386-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu DQ, Zhang H, Xiao L, Zhang BY, Liu WH. Single-operator cholangioscopy for the treatment of concomitant gallbladder stones and secondary common bile duct stones. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:929-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fischer S, Müller I, Zündt BZ, Jüngst C, Meyer G, Jüngst D. Ursodeoxycholic acid decreases viscosity and sedimentable fractions of gallbladder bile in patients with cholesterol gallstones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bellamy PR, Hicks A. Assessment of gallbladder function by ultrasound: implications for dissolution therapy. Clin Radiol. 1988;39:511-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tarantino G, Magistri P, Ballarin R, Assirati G, Di Cataldo A, Di Benedetto F. Surgery in biliary lithiasis: from the traditional "open" approach to laparoscopy and the "rendezvous" technique. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2017;16:595-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhou H, Jin K, Zhang J, Wang W, Sun Y, Ruan C, Hu Z. Single incision versus conventional multiport laparoscopic appendectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dig Surg. 2014;31:384-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Giovannucci E, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ. A meta-analysis of cholecystectomy and risk of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:130-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lin G, Zeng Z, Wang X, Wu Z, Wang J, Wang C, Sun Q, Chen Y, Quan H. Cholecystectomy and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:59-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lagergren J, Mattsson F, El-Serag H, Nordenstedt H. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after cholecystectomy. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:154-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zorrón R, Filgueiras M, Maggioni LC, Pombo L, Lopes Carvalho G, Lacerda Oliveira A. NOTES. Transvaginal cholecystectomy: report of the first case. Surg Innov. 2007;14:279-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Marescaux J, Dallemagne B, Perretta S, Wattiez A, Mutter D, Coumaros D. Surgery without scars: report of transluminal cholecystectomy in a human being. Arch Surg. 2007;142:823-6; discussion 826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sugimoto M, Yasuda H, Koda K, Suzuki M, Yamazaki M, Tezuka T, Kosugi C, Higuchi R, Watayo Y, Yagawa Y, Uemura S, Tsuchiya H, Hirano A, Ro S. Evaluation for transvaginal and transgastric NOTES cholecystectomy in human and animal natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | ASGE. ; SAGES. ASGE/SAGES Working Group on Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery White Paper October 2005. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:199-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Moris DN, Bramis KJ, Mantonakis EI, Papalampros EL, Petrou AS, Papalampros AE. Surgery via natural orifices in human beings: yesterday, today, tomorrow. Am J Surg. 2012;204:93-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu L, Chiu PW, Reddy N, Ho KY, Kitano S, Seo DW, Tajiri H; APNOTES Working Group. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) for clinical management of intra-abdominal diseases. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:565-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Akiyama D, Hamada T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Tsujino T, Umefune G, Takahara N, Mohri D, Kogure H, Matsubara S, Ito Y, Yamamoto N, Sasahira N, Tada M, Koike K. Superiority of 10-mm-wide balloon over 8-mm-wide balloon in papillary dilation for bile duct stones: A matched cohort study. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:213-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Disario JA, Freeman ML, Bjorkman DJ, Macmathuna P, Petersen BT, Jaffe PE, Morales TG, Hixson LJ, Sherman S, Lehman GA, Jamal MM, Al-Kawas FH, Khandelwal M, Moore JP, Derfus GA, Jamidar PA, Ramirez FC, Ryan ME, Woods KL, Carr-Locke DL, Alder SC. Endoscopic balloon dilation compared with sphincterotomy for extraction of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1291-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jowell PS, Baillie J, Branch MS, Affronti J, Browning CL, Bute BP. Quantitative assessment of procedural competence. A prospective study of training in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:983-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | ASGE Training Committee, Jorgensen J, Kubiliun N, Law JK, Al-Haddad MA, Bingener-Casey J, Christie JA, Davila RE, Kwon RS, Obstein KL, Qureshi WA, Sedlack RE, Wagh MS, Zanchetti D, Coyle WJ, Cohen J. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): core curriculum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:279-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |