Published online Jan 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.714

Peer-review started: September 28, 2020

First decision: November 3, 2020

Revised: November 20, 2020

Accepted: December 11, 2020

Article in press: November 11, 2020

Published online: January 26, 2021

Processing time: 114 Days and 6.7 Hours

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is high in China, and approximately 15%-20% of HCC cases occur in the absence of cirrhosis. Compared with patients with cirrhotic HCC, those with non-cirrhotic HCC have longer postoperative tumor-free survival. However, the overall survival time is not significantly increased, and the risk of postoperative recurrence remains. Strategies to improve the postoperative survival rate in these patients are currently required.

A 47-year-old man with a family history of HCC was found to have hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection 25 years ago. In 2000, he was administered lamivudine for 2 years, and entecavir (ETV 0.5 mg) was administered in 2006. In October 2016, magnetic resonance imaging revealed a tumor in the liver (5.3 cm × 5 cm × 5 cm); no intraoperative hepatic and portal vein and bile duct tumor thrombi were found; and postoperative pathological examination confirmed a grade II HCC with no nodular cirrhosis (G1S3). ETV was continued, and no significant changes were observed on imaging. After receiving pegylated interferon alfa-2b (PEG IFNα-2b) (180 μg) + ETV in February 2019, the HBsAg titer decreased significantly within 12 wk. After receiving hepatitis B vaccine (60 μg) in 12 wk, HBsAg serological conversion was realized at 48 wk. During the treatment, no obvious adverse reactions were observed, except for early alanine aminotransferase flares. The reexamination results of liver pathology were G2S1, and reversal of liver fibrosis was achieved.

The therapeutic regimen of ETV+ PEG IFNα-2b + hepatitis B vaccine for patients with HBV-associated non-cirrhotic HCC following hepatectomy can achieve an HBV clinical cure and prolong the recurrence-free survival.

Core Tip: Patients with hepatitis B virus infection can progress to liver failure, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); however, not all HCCs originate from cirrhosis, and approximately 15%-20% of HCC cases still occur without cirrhosis. Most importantly, the treatment of non-cirrhotic HCC after surgery and whether the risk of recurrence can be reduced by combining immunomodulators are the urgent problems that need to be solved at present. Therefore, we report a case in which HCC still occurred after 16 years of antiviral therapy, and the combination of immunoregulator therapy after HCC resection achieved a clinical cure and liver fibrosis reversal.

- Citation: Yu XP, Lin Q, Huang ZP, Chen WS, Zheng MH, Zheng YJ, Li JL, Su ZJ. Clinical cure and liver fibrosis reversal after postoperative antiviral combination therapy in hepatitis B-associated non-cirrhotic hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(3): 714-721

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i3/714.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.714

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common tumor and the second leading cause of cancer mortality in China[1], with 92.05% of HCC cases being caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection[2]. The Chinese population generally follow the trilogy of “chronic hepatitis B-liver cirrhosis-HCC”[3]. In this population, 75%-80% of HCC cases progressively originate from the regenerative or dysplastic nodules of liver cirrhosis, whereas 15%-20% occur without cirrhosis[4]. Compared with patients with cirrhotic HCC, those with non-cirrhotic HCC have the following characteristics: Usually single and large tumors; less deletion and mutation of tumor suppressor genes such as p53; stronger DNA mismatch repair; milder liver injury; better liver compensatory function; and, generally, no significant interferon contraindications[4,5]. Moreover, patients with non-cirrhotic HCC have a longer postoperative tumor-free survival, although the overall survival time does not significantly increase[5,6] and there is still a risk of postoperative recurrence. Currently, it is unclear whether clinical cure can reduce the risk of postoperative recurrence and improve survival rate in these patients. Therefore, we report the case of a patient with HBV-associated non-cirrhotic HCC who achieved a clinical cure and liver fibrosis reversal following treatment with entecavir (ETV) in combination with pegylated interferon alfa-2b (PEG IFNα-2b) and hepatitis B vaccine after hepatectomy for HCC.

A 47-year-old male patient who had HBV infection for 25 years and underwent hepatectomy for HCC 4 years ago was admitted to our institution.

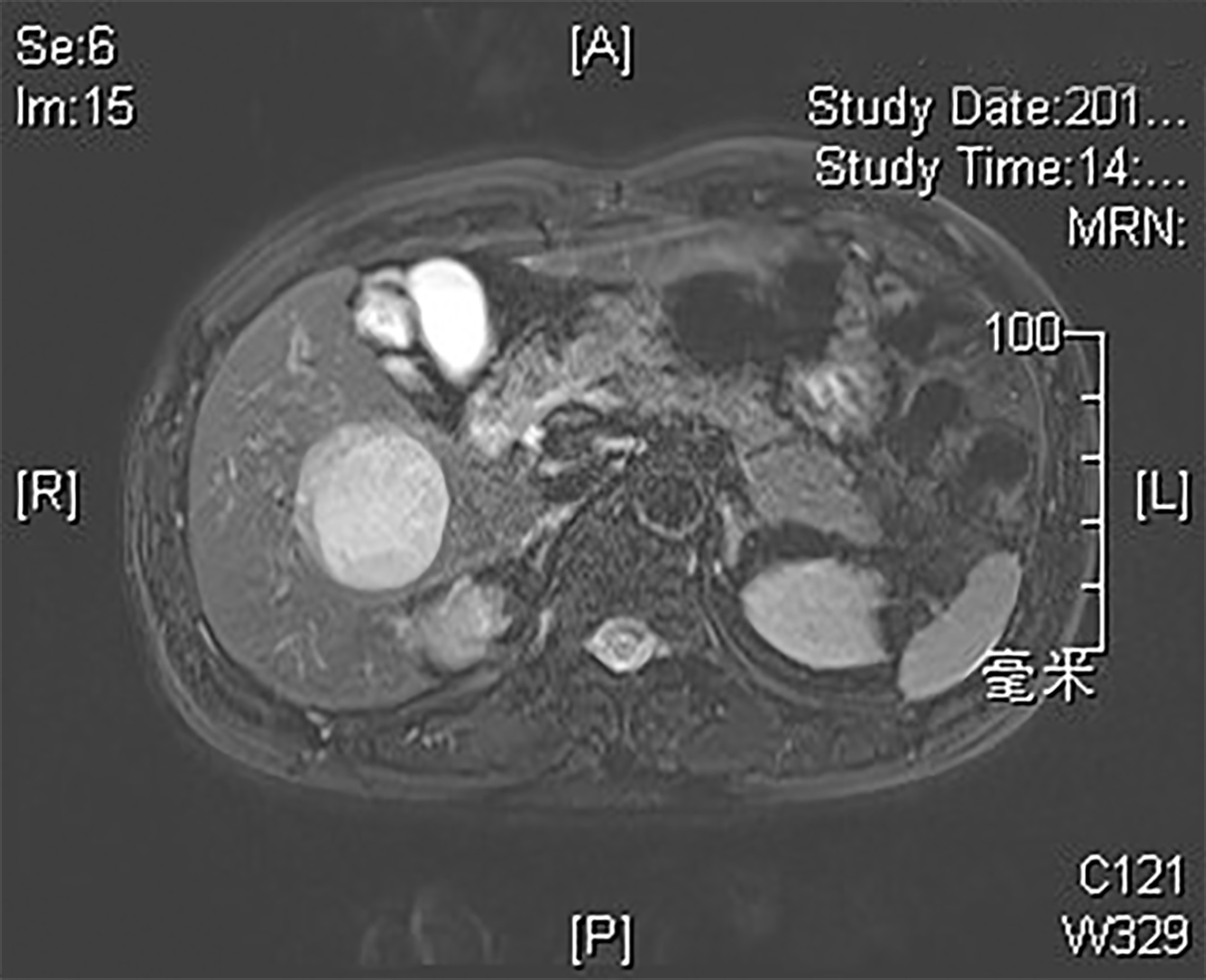

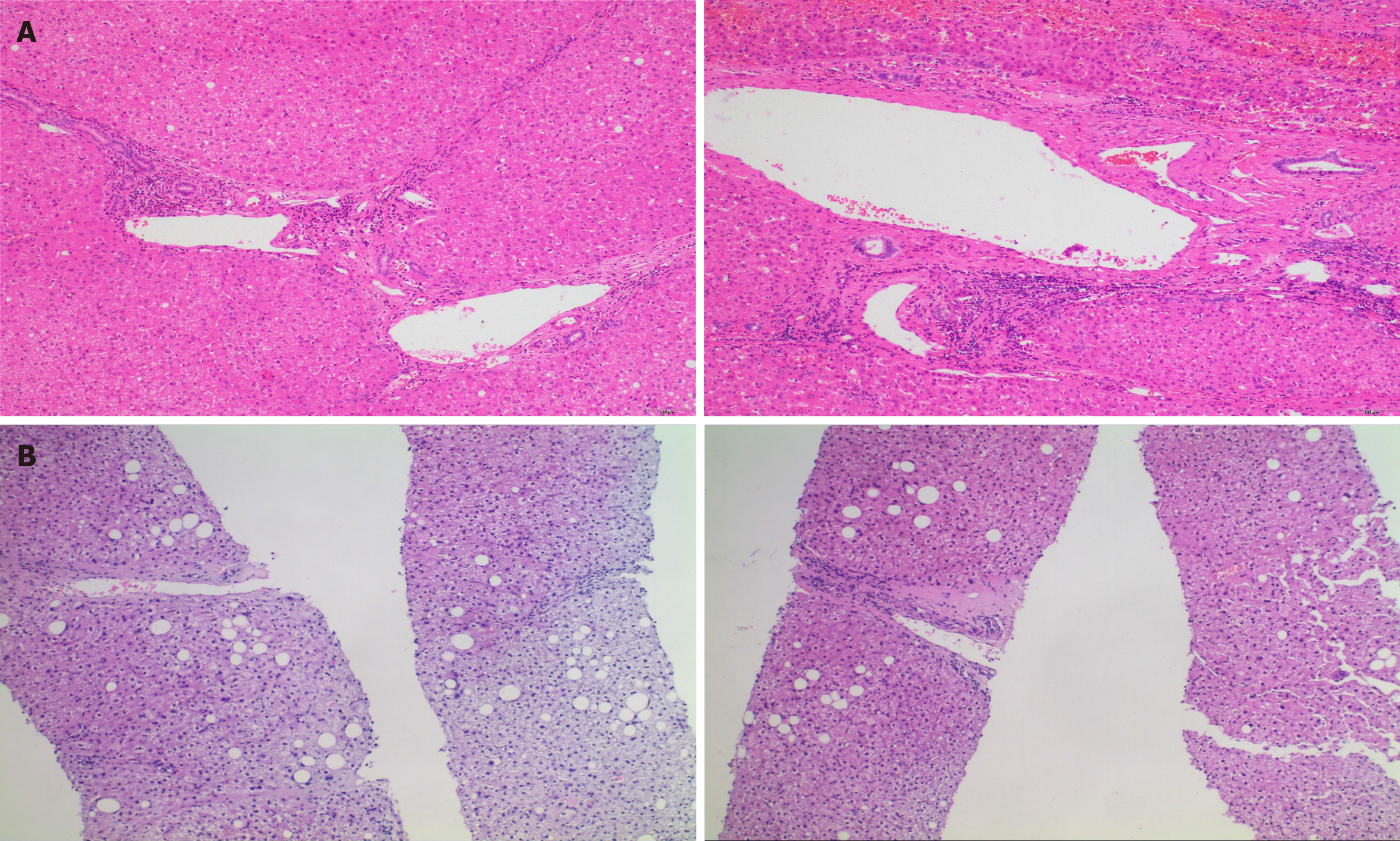

The patient was found to have HBV infection 25 years ago with normal liver function during follow-up. In 2000, he developed abnormal liver function and was diagnosed with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B, for which he was administered lamivudine (LAM) antiviral therapy; however, he discontinued the antiviral therapy after 2 years. In 2006, he was administered ETV antiviral therapy. In 2009, HBeAg seroconversion was achieved, and HBV DNA (Cobas) was maintained at < 20 IU/mL. In October 2016, color Doppler ultrasonography showed a space-occupying hepatic lesion, and it was confirmed to be an HCC (5.3 cm × 5 cm × 5 cm) by enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver at Zhongshan Hospital Affiliated to Fudan University (Figure 1). Subsequently, special segmental hepatectomy was performed. Intraoperatively, a tumor was found in segment V, with a complete capsule, clear boundary, and soft texture; moreover, no tumor thrombus was found in the hepatic and portal veins or bile ducts. Postoperative pathological examination confirmed a grade II HCC with no nodular cirrhosis (G1S3, Figure 2A). Postoperatively, the patient continued taking ETV, regular follow-ups revealed normal liver function, and MRI findings did not change significantly.

The patient had no previous noteworthy medical history.

The patient did not smoke tobacco or consume alcohol. His father died of HCC in 1974.

The patient’s height and weight were 176 cm and 76 kg, respectively. The patient had a body temperature of 36.2 °C, blood pressure of 145/78 mmHg, and pulse rate of 76 beats/min. The abdomen was soft and flat, with no pain or tenderness. No edema of the lower extremities was observed.

The results of the analyses performed on February 27, 2019 before the initial treatment, were as follows: For serology (Abbott), HBsAg, 572.03 IU/mL; HBeAb, 0.79 S/CO; HBcAb, 1.13 S/CO; and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), 3.06 ng/mL; for biochemistry, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 22 U/L; and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 25 U/L; for virology, HBV DNA (cobas), < 20 IU/mL; and for the blood routine test, white blood cell count, 6.38 × 109/L; neutrophil count, 2.21 × 109/L; and platelet count, 156 × 109/L. The results of the thyroid function tests (TSH, FT3, and FT4) were normal; autoimmune liver disease-related antibodies were all negative.

Electrocardiography was normal, and abdominal color Doppler ultrasonography and liver ultrasound scans showed slightly coarse images, with no nodules or space-occupying lesions.

HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B; non-cirrhotic HCC after hepatectomy.

The treatment regimen was PEG IFNα-2b (180 μg qw, Amoytop Biotech Co., LTD., Xiamen, China) + ETV (0.5 mg qd, Bristol Myers Squibb Co., NY, United States). After 12 wk, hepatitis B vaccine (60 μg qm, Shenzhen Kangtai Biological Products Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) was added.

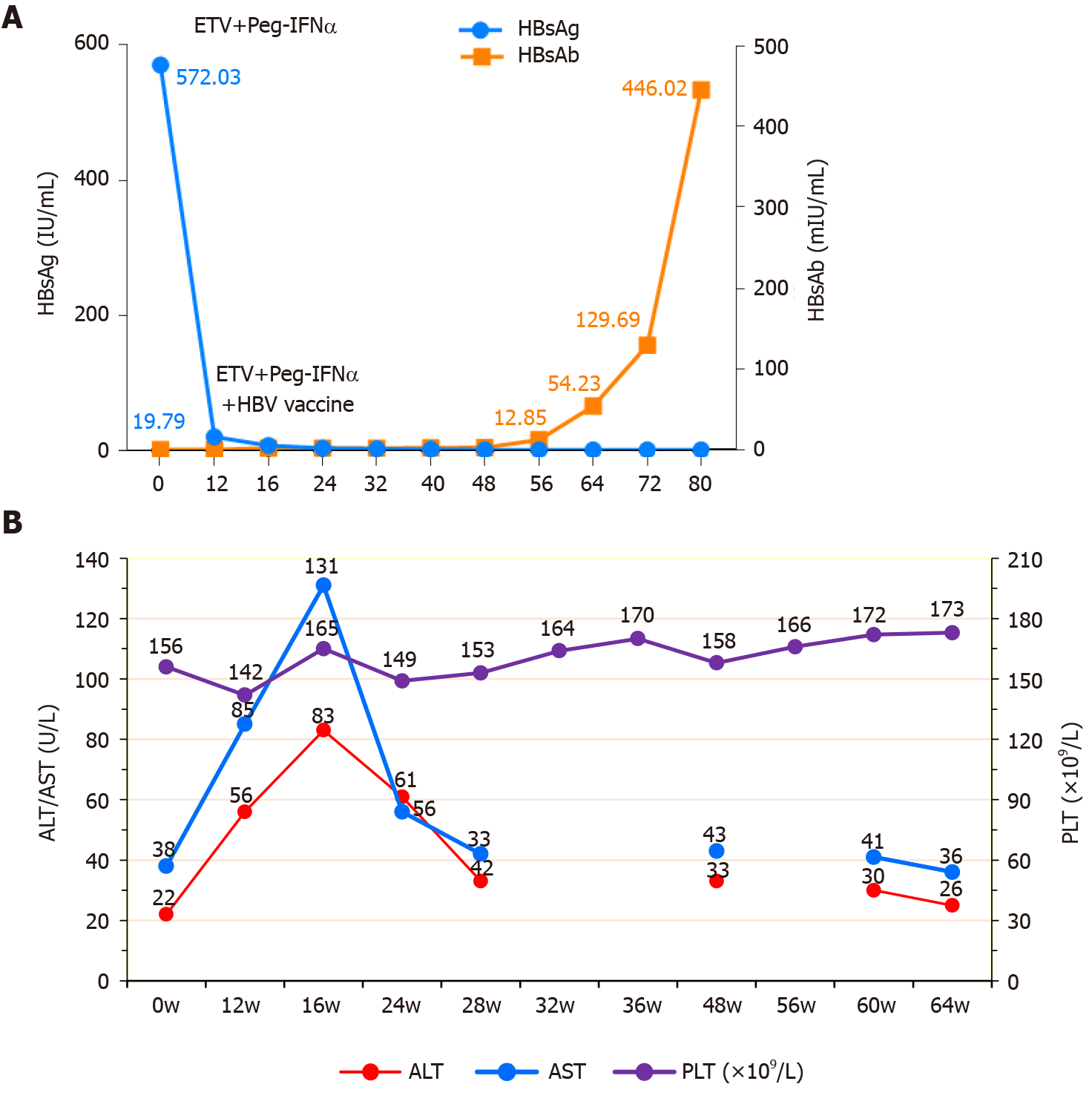

Before the combined treatment, the scores of the FIB-4[7] and APRI[8], two recognized indices for noninvasive liver fibrosis, were 2.39 and 24.36, respectively. No significant adverse reactions were found during the combined treatment, and the routine blood and biochemistry indices varied within the normal range. After 12 wk of treatment, HBsAg decreased (572.0 to 19.79 IU/mL), ALT and AST levels increased (ALT/AST, 56/85 U/L), and hepatitis B vaccine was added as monthly treatment. After 16 wk of treatment, HBsAg further decreased, HBsAb increased, and ALT and AST levels peaked (ALT/AST, 83/131 U/L). After 28 wk of treatment, HBsAg and HBsAb further increased (2.38 mIU/mL), whereas ALT and AST levels decreased to normal levels. After 48 wk of treatment, HBsAb further increased (12.85 mIU/mL), and ALT and AST levels normalized. After 60 wk of treatment, HBsAg disappeared with seroconversion, whereas HBsAb further increased (129.69 mIU/mL). After 64 wk of treatment, the scores of the FIB-4 and APRI were significantly reduced (1.13 and 14.45, respectively), and HBsAb further increased to 446.02 mIU/mL, reaching the level of clinical cure (Figure 3).

On July 12, 2020 (60 wk), a liver puncture biopsy was performed and assessed, showing slightly disordered arrangement of hepatic plates, swollen hepatocytes with some showing balloon-like changes, focal and narrow strip-like necrosis, a small amount of lymphocyte infiltration in the portal area, and mild interfacial inflammation, findings consistent with chronic hepatitis (G2S1, Figure 2B). Immunohistochemistry showed negative HBsAg and HBcAg results. Compared with the pathological results of HCC resection in October 2016 (Zhongshan Hospital, Shanghai, G1S3), the degree of fibrosis was significantly reversed.

This paper reports a patient with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B who had been treated with long-term oral ETV antiviral therapy and was regularly followed in the outpatient clinic. The AFP level was consistently normal. When HCC was found on color Doppler ultrasonography, there were no signs of clinical discomfort or metastasis, such as portal vein and bile duct tumor thrombi. After timely surgical treatment, survival was prolonged. Therefore, reexamination by AFP analysis and color Doppler ultrasonography or enhanced CT/MRI regularly every 3-6 mo to detect HCC at an early stage is particularly important for reducing HCC mortality.

This patient had no discomfort, and his liver function was normal, with a single large tumor on imaging. Postoperative pathological analyses confirmed no cirrhosis or nodules; therefore, he was classified as a patient with non-cirrhotic HCC. Such patients have been shown to have a good prognosis after early surgical resection; however, the risk of postoperative HCC recurrence persists[9]. Several factors can affect postoperative HCC recurrence, among which HBsAg is the main virus factor[10,11]. The higher the HBsAg level, the higher the long-term postoperative recurrence rate[12]. During the seroconversion or disappearance of HBsAg, the long-term recurrence rate of HCC decreases significantly[13]. Interferon not only has antiviral, anti-fibrosis, and antitumor effects (or prevents HCC recurrence) but also inhibits HBsAg production and even eliminates HBsAg[14]. In 2019, a study showed that when the HBsAg titers of patients treated with nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs) were ≤ 1500 IU/mL, NA sequential/combination therapy with PEG IFNα-2b is conducive to reducing or even eliminating HBsAg and achieving a clinical cure[15]. However, there are still a small number of reports on PEG IFNα-2b combination therapy for postoperative treatment of patients with HCC, especially those without liver cirrhosis. The current patient was treated with a combination therapy of ETV + PEG IFNα-2b + hepatitis B vaccine. Currently, HBsAg seroconversion has been achieved, suggesting a clinical cure for HBV infection. Severe liver fibrosis is a risk factor for postoperative HCC recurrence[16]; moreover, the higher the degree of liver fibrosis, the higher the postoperative recurrence risk[16,17]. Previous studies have shown that the resolution of fibrosis occurred in HBV-infected patients after NAs or IFNα treatment[18,19]. After 60 wk of a combination therapy of ETV + PEG IFNα-2b, the pathological reexamination results of the liver tissue showed that liver fibrosis was significantly reversed (S3 to S1). The noninvasive liver fibrosis indices also decreased significantly (FIB-4, 2.39 to 1.13; APRI, 24.36 to 14.45). Thus, the resolution of fibrosis indicated that the possibility of HCC recurrence was significantly reduced. However, due to the short follow-up period, further studies are required to clarify the risk of long-term HCC recurrence.

Hepatitis B vaccine can activate host immune cells and induce the expression of dendritic cells and specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes, thereby improving the response rate to PEG IFNα-2b, reducing the HBsAg level, and promoting the secretion of anti-HBs[20,21]. For immunocompromised or unresponsive adults, the vaccination dose (60 μg) or administration frequency should be increased[3]; hence, it is safe and effective to apply combination therapy with 60 μg of hepatitis B vaccine for this patient.

An acute elevation of ALT is mainly immune-mediated, which may mark the transition to inactive disease or infection clearance[22]. Patients, more commonly, experience an acute elevation of ALT during PEG IFNα-2b treatment, and such patients achieve better treatment outcomes. An open-label, multicenter study in South Korea included 740 patients with chronic hepatitis B who received tenofovir (TDF) or PEG IFNα alone or in combination and were followed for 120 wk. The results showed that the acute elevation of ALT caused by PEG IFNα generally occurred in the first 4 wk of treatment, and TDF monotherapy rarely caused such elevation[23]. Another international, multicenter, randomized controlled study retrospectively analyzed the relationship between the acute elevation of ALT and clinical benefits in a PEG IFNα + LAM combination group and a placebo group (treatment for 48 wk and follow-up for 24 wk). The results showed that the acute elevation of ALT mediated by host immunity was higher than the virus-mediated clearance rate of HBeAg (58% vs 20%, P = 0.008), and HBsAg clearance was achieved in eight patients with acute elevation of ALT mediated by host immunity[24].

It is suggested that PEG IFNα-2b therapy should be used earlier in the high-risk groups such as those with a family history of HCC. If combined PEG IFNα-2b is applied before HCC occurrence, the outcome may be different, and HCC may either not occur or its occurrence may be delayed. Even if HCC occurs, PEG IFNα-2b combination should be added postoperatively as early as possible to reduce the risk of HCC recurrence and prolong patient survival. It is important to determine whether this patient should continue the use of ETV antiviral therapy after using interferon for the maximum treatment course of 96 wk or discontinue it early. Patients with liver cirrhosis require long-term antiviral therapy[3], while those with HCC complicating HBV infection should be treated with oral antiviral therapy throughout the treatment process[25]. Although this patient did not experience cirrhosis, he still developed HCC; therefore, he should be treated with long-term ETV antiviral therapy.

HCC may still occur after antiviral treatment with NAs; thus, it is necessary to check the AFP level and color Doppler ultrasound regularly for 3-6 mo. For patients with non-cirrhotic HCC, if there are no contraindications to interferon, the therapeutic regimen of NAs combined with PEG IFNα and hepatitis B vaccine following hepatectomy should be used as soon as possible to achieve an HBV clinical cure and improve the recurrence-free survival rate.

We gratefully thank all the medical staff at The Department of Infectious Diseases of The First Hospital of Quanzhou Affiliated to Fujian Medical University for the collection of clinical specimens.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Macias Rodriguez RU, Manautou JE, Ozaki I S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Xiao J, Wang F, Wong NK, He J, Zhang R, Sun R, Xu Y, Liu Y, Li W, Koike K, He W, You H, Miao Y, Liu X, Meng M, Gao B, Wang H, Li C. Global liver disease burdens and research trends: Analysis from a Chinese perspective. J Hepatol. 2019;71:212-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 63.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Qin S. Interim Report on primary Liver Cancer Clinical Registry survey (CLCS) in China. In: Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology, 2019. |

| 3. | Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association, Chinese Society of Hepatology. Guideline on prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B in China (2019 edition). Zhonghua Chuanran Bing Zazhi. 2019;37:711-736. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Yang SL, Liu LP, Sun YF, Yang XR, Fan J, Ren JW, Chen GG, Lai PB. Distinguished prognosis after hepatectomy of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma with or without cirrhosis: a long-term follow-up analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:722-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gawrieh S, Dakhoul L, Miller E, Scanga A, deLemos A, Kettler C, Burney H, Liu H, Abu-Sbeih H, Chalasani N, Wattacheril J. Characteristics, aetiologies and trends of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients without cirrhosis: a United States multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:809-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim JM, Kwon CH, Joh JW, Park JB, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Paik SW, Park CK, Yoo BC. Differences between hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus infection in patients with and without cirrhosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:458-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, S Sulkowski M, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL, Messinger D, Nelson M; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 3536] [Article Influence: 186.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2762] [Cited by in RCA: 3235] [Article Influence: 147.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Qi W, Zhang Q, Xu Y, Wang X, Yu F, Zhang Y, Zhao P, Guo H, Zhou C, Wang Z, Sun Y, Liu L, Xuan W, Wang J. Peg-interferon and nucleos(t)ide analogue combination at inception of antiviral therapy improves both anti-HBV efficacy and long-term survival among HBV DNA-positive hepatocellular carcinoma patients after hepatectomy/ablation. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27:387-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xu XF, Xing H, Han J, Li ZL, Lau WY, Zhou YH, Gu WM, Wang H, Chen TH, Zeng YY, Li C, Wu MC, Shen F, Yang T. Risk Factors, Patterns, and Outcomes of Late Recurrence After Liver Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Multicenter Study From China. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:209-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 64.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qiu JF, Ye JZ, Feng XZ, Qi YP, Ma L, Yuan WP, Zhong JH, Zhang ZM, Xiang BD, Li LQ. Pre- and post-operative HBsAg levels may predict recurrence and survival after curative resection in patients with HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:140-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou HB, Li QM, Zhong ZR, Hu JY, Jiang XL, Wang H, Wang H, Yang B, Hu HP. Level of hepatitis B surface antigen might serve as a new marker to predict hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence following curative resection in patients with low viral load. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:756-771. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kubo S, Hirohashi K, Tanaka H, Tsukamoto T, Shuto T, Higaki I, Takemura S, Yamamoto T, Nishiguchi S, Kinoshita H. Virologic and biochemical changes and prognosis after liver resection for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2001;18:26-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tian S, Hui X, Fan Z, Li Q, Zhang J, Yang X, Ma X, Huang B, Chen D, Chen H. Suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation and hepatitis B surface antigen secretion with interferon-λ1 or PEG-interferon-λ1. FASEB J. 2014;28:3528-3539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ning Q, Wu D, Wang GQ, Ren H, Gao ZL, Hu P, Han MF, Wang Y, Zhang WH, Lu FM, Wang FS. Roadmap to functional cure of chronic hepatitis B: An expert consensus. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:1146-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Suh SW, Choi YS. Influence of liver fibrosis on prognosis after surgical resection for resectable single hepatocellular carcinoma. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:211-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ko S, Kanehiro H, Hisanaga M, Nagao M, Ikeda N, Nakajima Y. Liver fibrosis increases the risk of intrahepatic recurrence after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2002;89:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z, Chi YC, Zhang H, Hindes R, Iloeje U, Beebe S, Kreter B. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 51.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, Afdhal N, Sievert W, Jacobson IM, Washington MK, Germanidis G, Flaherty JF, Aguilar Schall R, Bornstein JD, Kitrinos KM, Subramanian GM, McHutchison JG, Heathcote EJ. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013;381:468-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1228] [Cited by in RCA: 1364] [Article Influence: 113.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shaaban Hanafy A. Impact of hepatitis B vaccination on HBsAg kinetics, interferon-inducible protein 10 level and recurrence of viremia. Cytokine. 2017;99:99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee JH, Lee YB, Cho EJ, Yu SJ, Yoon JH, Kim YJ. Entecavir Plus Pegylated Interferon and Sequential HBV Vaccination Increases HBsAg Seroclearance: A Randomized Controlled Proof-of-Concept Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ghany MG, Feld JJ, Chang KM, Chan HLY, Lok ASF, Visvanathan K, Janssen HLA. Serum alanine aminotransferase flares in chronic hepatitis B infection: the good and the bad. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:406-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ahn SH, Marcellin P, Ma X, Caruntu FA, Tak WY, Elkhashab M, Chuang WL, Tabak F, Mehta R, Petersen J, Guyer W, Jump B, Chan A, Subramanian M, Crans G, Fung S, Buti M, Gaeta GB, Hui AJ, Papatheodoridis G, Flisiak R, Chan HLY. Correction to: Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Loss with Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Plus Peginterferon Alfa-2a: Week 120 Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:285-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Flink HJ, Sprengers D, Hansen BE, van Zonneveld M, de Man RA, Schalm SW, Janssen HL; HBV 99-01 Study Group. Flares in chronic hepatitis B patients induced by the host or the virus? Gut. 2005;54:1604-1609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Department of Medical Administration, National Health and Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of primary Liver cancer (2019 edition). Zhonghua Ganzang Bing Zazhi. 2020;112-128. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |