Published online Jan 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.685

Peer-review started: September 12, 2020

First decision: November 30, 2020

Revised: December 4, 2020

Accepted: December 16, 2020

Article in press: December 16, 2020

Published online: January 26, 2021

Processing time: 127 Days and 22.2 Hours

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a highly infectious pathogen that is easily transmitted via the bodily fluids of an infected individual. This virus usually affects individuals older than six months of age, and rarely causes lesions or symptoms in younger patients.

We present the case of a five-month-old healthy girl who presented with painful herpetic gingivostomatitis and perioral vesicles. We discuss the pathophysiology of primary HSV infection and the effect of maternal antibodies on the infant’s immune system. In addition, we explain the diagnosis, management, and prognosis of HSV infection in young infants.

This case highlights the importance of early diagnosis and management of HSV infections to decrease the risk of developing severe complications and death.

Core Tip: Although the herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection is highly contagious, it rarely develops in infants younger than six months of age. Our patient presented with oral and perioral manifestations of HSV type 1 infection. Early diagnosis and management of HSV infections is important to decrease the risk of developing severe complications.

- Citation: Aloyouny AY, Albagieh HN, Al-Serwi RH. Oral and perioral herpes simplex virus infection type I in a five-month-old infant: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(3): 685-689

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i3/685.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.685

There are two known subtypes of herpes simplex virus (HSV): Type 1 and type 2. Infection with HSV type 1 is usually associated with oral and perioral lesions, while infection with HSV type 2 is associated with genital lesions.

HSV infection usually affects children between the ages of six months and four years and rarely develops in children younger than six months of age. However, in this case study, we report the case of a five-month-old healthy girl who presented with herpetic gingivostomatitis and perioral vesicles. Primary herpetic infection is very rare in this age. A review of the literature yielded few reported cases.

A five-month-old healthy girl was referred to an oral medicine clinic for evaluation of oral and perioral lesions.

The patient had a three-day-history of oral and perioral lesions accompanied by fever (38.6 °C), irritability, poor breastfeeding, and poor sleep.

The patient’s mother denied the presence of previous surgical procedures, pathologic medical diagnoses, or genetic conditions for the patient.

The patient was born via cesarean delivery to a 37-year-old primigravid. She has been exclusively breastfed by her mother since birth with no intake of bottled milk. The mother has a history of recurrent intraoral HSV infections, and her last infection reportedly occurred seven weeks before the patient presented with primary perioral and oral HSV type 1infection. The mother’s anti-HSV-1 immunoglobulin (Ig) G level was 0.6 (seronegative) and her anti-HSV-2 IgG level was 0.4 (seronegative).

Physical and systemic examination: The patient was born in good health and has not taken any medications since birth.

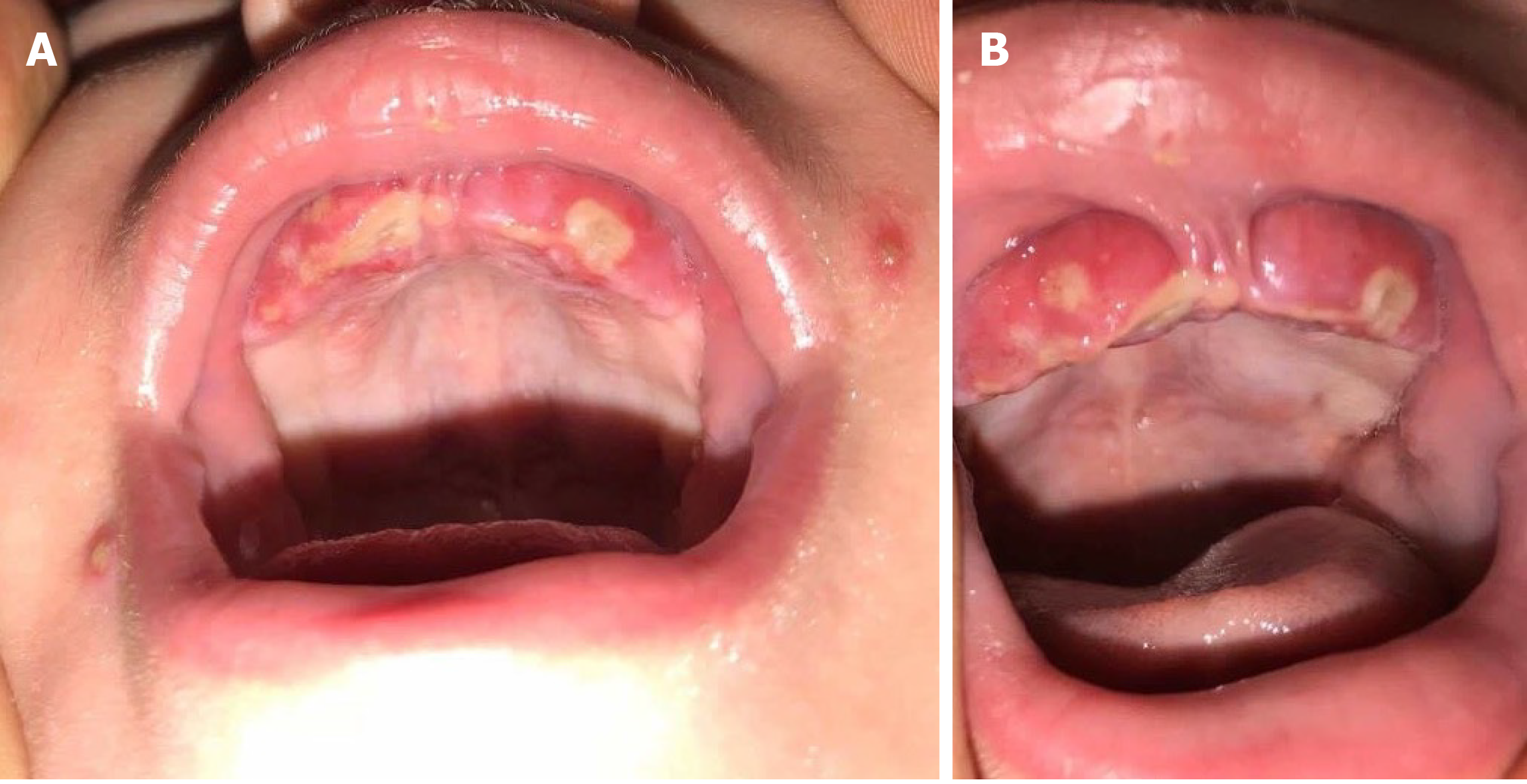

Extraoral examination: Extraoral examination showed multiple perioral vesicular eruptions with crusted surfaces and erythematous halos (Figure 1A). Excessive drooling and submandibular lymphadenopathy were also observed.

Intraoral examination: Intraoral examination revealed a swollen, red gingiva with multiple ulcers at the upper anterior alveolar ridge with a yellow-gray coating (Figure 1). In addition, the examination revealed swollen palatine tonsils and halitosis.

Blood tests revealed normal results: a red blood cell count of 4.2 × 106/μL, a hemoglobin count of 12.4 g/dL, a platelet count of 432 × 103/μL, and a white blood cell count of 15.6 × 103/μL with 41% segmented neutrophils and 62% lymphocytes.

Not applicable.

The main differential diagnoses in this case included HSV type 1, HSV type 2, herpangina, and varicella zoster virus infection.

As part of the HSV infection workup, diagnostic procedures were carried out to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. Tzanck smear, which was taken from an oral sore and a perioral vesicle, showed multinucleated giant cells with inclusion bodies. Additionally, HSV-1 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and IgM testing for HSV-1 yielded positive findings. All results were consistent with HSV type 1 infection.

The final diagnosis in this case was perioral and oral ulcerations due to HSV type 1 infection.

The infant was transferred to a hospital for better management of her infection. She was immediately started on IV acyclovir (20 mg/kg/6 h/5 d) while acetaminophen suppositories (80 mg/8 h/5 d) were given to lower her body temperature. In addition, other palliative drugs, such as diphenhydramine syrup (12.5 mg/5 mL, 2.5 mL orally) once-a-night for five days, were given to ease the effort of drinking and to aid in achieving good sleep. Upon completion of five days of therapy, the patient showed complete recovery and was subsequently discharged from the hospital free from symptoms.

During a follow-up consult conducted a week after she was discharged, the patient’s oral and perioral lesions had healed completely without scarring. During a follow-up visit one month later, the patient was noted to be healthy and lesion-free; she had also gained some weight as feeding became comfortable once more. The patient was re-examined at the age of one year and no recurrence of HSV infection or complications were noted.

HSV is a DNA virus that has two subtypes: Type 1 and type 2. Infections with HSV type 1 usually manifests in areas above the waist, such as oral and perioral infections, whereas HSV type 2 infections occur below the waist, such as genital infections.

Primary oral HSV type 1 herpetic infection is very uncommon in newborns and infants younger than six months. In these rare cases, the infection ranges from a subclinical and asymptomatic condition to severe and symptomatic disease. Initially, HSV invades neural, epidermal, and dermal tissues before replicating. During viral contact with the skin, the virus travels to the sensory dorsal root ganglion where a latent stage begins. HSV type 1 then becomes reactivated from the trigeminal sensory ganglia to affect different parts of the facial mucosa, including the oral and perioral regions[1].

Primary oral HSV type 1 infection may manifest with prodromal symptoms before herpetic gingivostomatitis, perioral lesions, and lymphadenopathy develop. Intraoral lesions include painful vesicles on swollen, raw, and red bases. Afterwards, the vesicles rupture, leaving behind ulcerated lesions. Type 1 infections usually heal within 10 to 14 d[2].

Maternal antibodies normally cross the placenta passively during pregnancy, thereby increasing the newborn’s immune system during the first six-months of life[3]. However, in very rare cases (approximately 1% of all adult cases), mothers do not develop antibodies against HSV and remain seronegative for the virus. Therefore, the lack of antibodies in an infant, due to their immature immune system, and the lack of maternal antibodies transmitted to the fetus through the placenta during pregnancy, may be risk factors for the early development of HSV infection[4,5].

In vaginal deliveries, the neonate is exposed to the virus as it passes through the birth canal, thereby increasing the risk of mother-to-infant viral transmission[6]. This patient was born via cesarean delivery, which has a lower risk of viral transmission compared to vaginal delivery.

Confirmation of the diagnosis depends on isolation of the virus from active lesions using methods such as Tzanck smear and viral culture. Direct fluorescent antibody test (antigen detection) and PCR for viral DNA detection can also be used to confirm the diagnosis. On the other hand, indirect tests for HSV include enzyme immunoassay and western blotting[7].

The prognosis of HSV in infants depends on the patient’s health and immunological status. Acyclovir is the first-line therapy for HSV. Symptom relief using antipyretics, antihistamine therapies, and intravenous fluid hydration also aid and hasten recovery. Infection with HSV has a high recurrence rate; therefore, follow-up is highly encouraged to decrease the severity and number of HSV attacks[2].

Guardians must ensure that the infant does not touch their mouth or saliva to prevent autoinoculation of the virus on scratched fingers, which can lead to the development of herpetic whitlow, and on the patient’s eyes, which may lead to herpes simplex keratitis. Herpes simplex keratitis can cause pain, discomfort, permanent eye damage, and even blindness[8].

It is very uncommon for infants younger than six months to be infected with HSV. However, when it does occur, HSV infection can lead to severe, and sometimes fatal, disease. Therefore, pediatricians, physicians, and dentists should include HSV infection in the differential diagnosis list of young infants with oral and perioral lesions to allow for early diagnosis and treatment.

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University through the Fast-track Research Funding program.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Academy of Oral Medciine.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li P S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Usatine RP, Tinitigan R. Nongenital herpes simplex virus. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:1075-1082. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Cernik C, Gallina K, Brodell RT. The treatment of herpes simplex infections: an evidence-based review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1137-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kasubi MJ, Nilsen A, Marsden HS, Bergström T, Langeland N, Haarr L. Prevalence of antibodies against herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in children and young people in an urban region in Tanzania. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2801-2807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Taieb A, Body S, Astar I, du Pasquier P, Maleville J. Clinical epidemiology of symptomatic primary herpetic infection in children. A study of 50 cases. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1987;76:128-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Batalla A, Flórez A, Dávila P, Ojea V, Abalde T, de la Torre C. Genital primary herpes simplex infection in a 5-month-old infant. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:8. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Buckley KS, Kimberlin DW, Whitley RJ. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Herpes Simplex Viruses. 2005: 395-410. |

| 7. | Singh A, Preiksaitis J, Ferenczy A, Romanowski B. The laboratory diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infections. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16:92-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pinninti SG, Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. Semin Perinatol. 2018;42:168-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |