Published online Jan 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.666

Peer-review started: September 1, 2020

First decision: November 8, 2020

Revised: November 16, 2020

Accepted: November 29, 2020

Article in press: November 29, 2020

Published online: January 26, 2021

Processing time: 141 Days and 3.8 Hours

Paragonimiasis is a parasitic disease that has multiple symptoms, with pulmonary types being common. According to our clinical practices, the pleural effusion of our patients is full of fibrous contents. Drainage, praziquantel, and triclabendazole are recommended for the treatment, but when fibrous contents are contained in pleural effusion, surgical interventions are necessary. However, no related reports have been noted. Herein, we present a case of pulmonary paragonimiasis treated by thoracoscopy.

A 12-year-old girl presented to our outpatient clinic complaining of shortness of breath after exercise for several days. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed positivity for antibodies against Paragonimus westermani, serological test showed eosinophilia, and moderate left pleural effusion and calcification were detected on computed tomography (CT). She was diagnosed with paragonimiasis, and praziquantel was prescribed. However, radiography showed an egg-sized nodule in the left pleural cavity during follow-up. She was then admitted to our hospital again. The serological results were normal except slight eosinophilia. CT scan displayed a cystic-like node in the lower left pleural cavity. The patient underwent a thoracoscopic mass resection. A mass with a size of 6 cm × 4 cm × 3 cm adhered to the pleura was resected. The pathological examination showed that the mass was composed of non-structured necrotic tissue, indicating a granuloma. The patient remainded asymptomatic and follow-up X-ray showed complete removal of the mass.

This case highlights that thoracoscopic intervention is necessary when fibrous contents are present on CT scan or chest roentgenogram to avoid later fibrous lump formation in patients with pulmonary paragonimiasis.

Core Tip: Paragonimiasis is a common parasitic disease in south China. Based on our clinical experience, the pleural effusion of our patients contains abundant scrambled egg-like materials, and it is difficult to drain all the fluid because the fibrous materials can block the drainage tube. Therefore, the fibrous material can lead to fibrous lump formation. However, there have been rare reports about surgical interventions performed on patients with pleural effusion, hence we recommend early intervention in pleural effusion to prevent the development of the chronic stage.

- Citation: Xie Y, Luo YR, Chen M, Xie YM, Sun CY, Chen Q. Pleural lump after paragonimiasis treated by thoracoscopy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(3): 666-671

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i3/666.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.666

Paragonimiasis is a typical parasitic disease caused by foodborne zoonotic helminthiasis named paragonimus. Human infections often happen after the ingestion of freshwater crustaceans, crabs, or crayfishes, which were infected by Paragonimus metacercariae[1]. This disease prevails mainly in Asian, Latin America, and Africa, especially areas where the residents habitually take raw or undercooked water or food[2-4]. The invasion of metacercariae causes different clinical symptoms, including subcutaneous, pleurisy, abdominal, cerebral, and asymptomatic types. The pleurisy type is the most common, which presents as chest pain, cough, and pleural effusion. Praziquantel and triclabendazole are potent for the treatment of paragonimiasis and are recommended by the World Health Organization. However, it has been reported that praziquantel is insufficient in massive pleural effusion cases[1], so drainage is suggested, while surgical intervention has not been narrated. But according to our clinical practices, pleural effusion is hard to be removed by drainage due to the numerous fibrous materials inside the fluid, hence we recommend thoracoscopy in such situations. Here, we report one patient who presented a thoracic lump after standard praziquantel treatment and was cured by thoracoscopic mass resection.

A 12-year-old girl presented to our outpatient clinic with shortness of breath after exercise for several days.

The patient’s symptoms started several days ago with shortness of breath after exercise, without symptoms of cough and thoracalgia.

The patient had a history of ingesting raw crabs and a free previous medical history.

The patient had no specific personal and family history.

After admission, the patient’s vital signs were normal. The breath sounds of the left lung were reduced; neither wet rales nor dry rales were revealed on both lungs.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed positivity for antibodies against Paragonimus westermani. The serological test showed eosinophilia at the first hospitalization. Serological results (basic metabolic panel and tumor markers) were normal, except slight eosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count, 0.61 × 109 /L) at the second hospitalization.

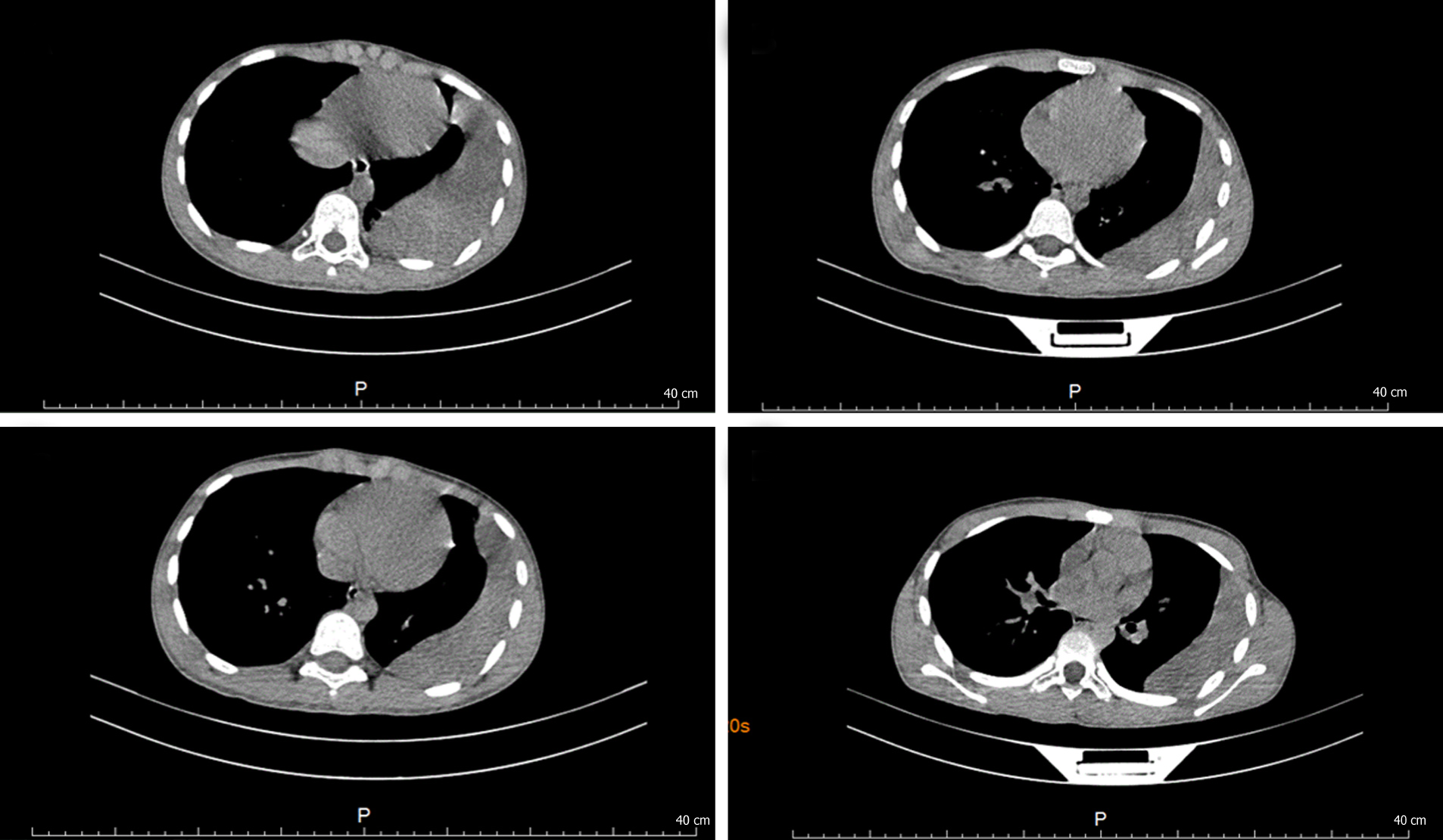

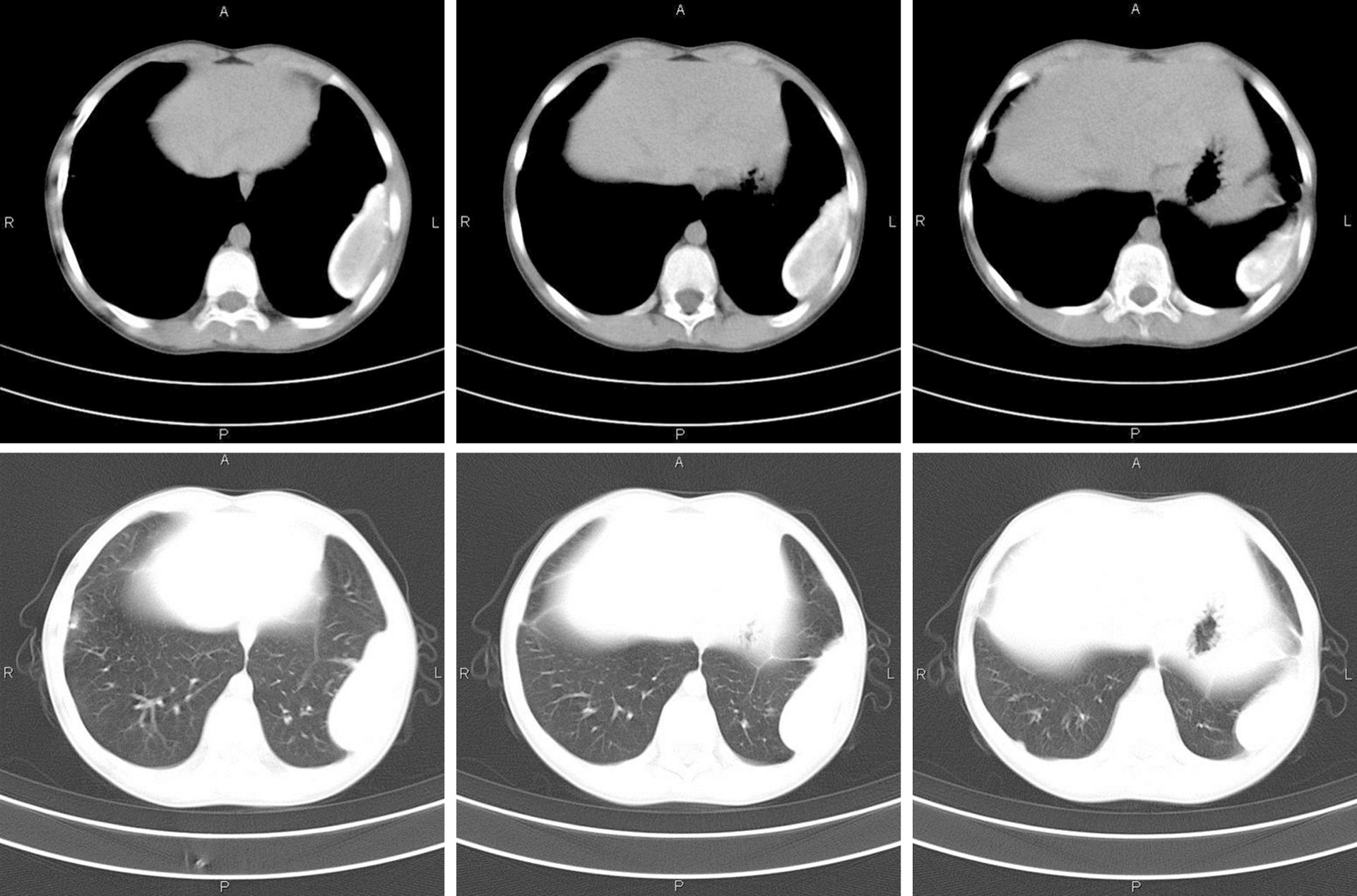

At the first hospitalization, CT scan showed moderate left pleural effusion, left pleural thickening, and calcification (Figure 1). At the second hospitalization, CT scan displayed a cystic-like node (6.0 cm × 2.3 cm) in the lower left pleural cavity (Figure 2).

A diagnosis of paragonimiasis with pleural lump was made by clinical symptoms, laboratory, and imaging examinations.

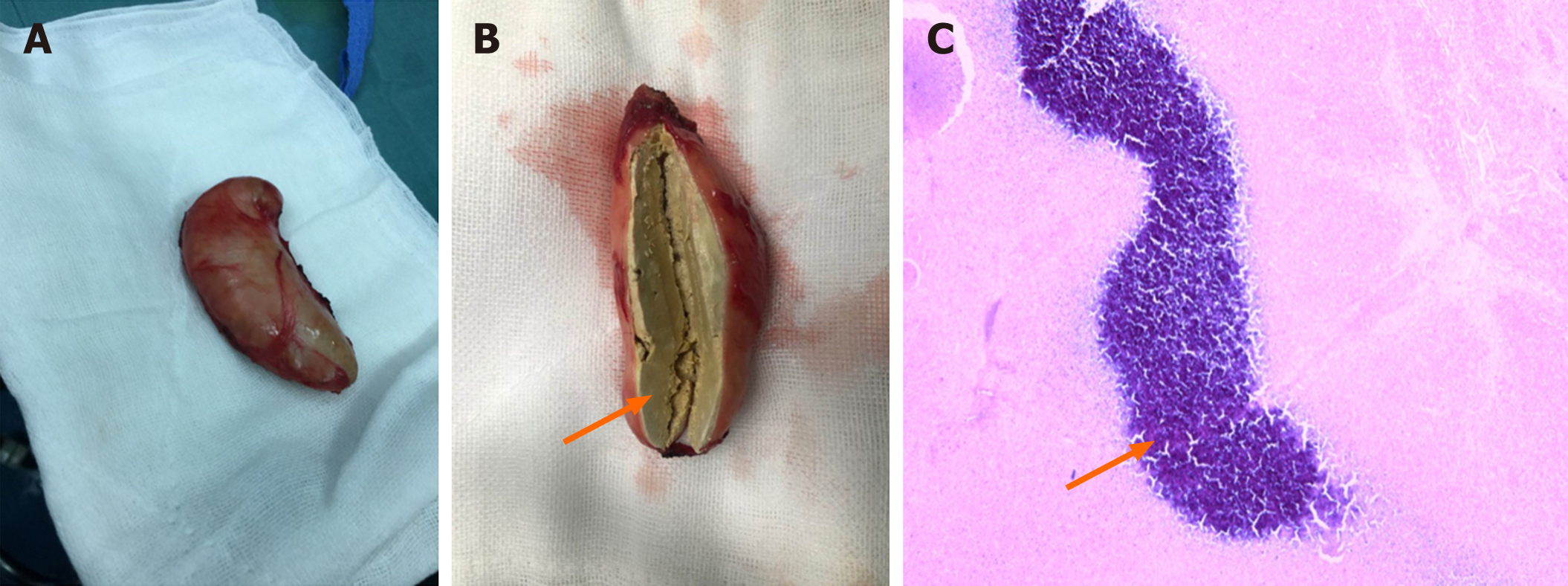

Praziquantel was prescribed for the patient at the first hospitalization. At the second admission, the patient underwent a thoracoscopic mass resection. A mass that adhered to the pleura and compressed the lower left lobe, which had a size of 6 cm × 4 cm × 3 cm and curved moon shape and was enveloped by fibrous tissue, was resected during the operation (Figure 3). We postulated that it was the necrotic residue of paragonimus.

The patient was discharged on the fifth day post operation. She was seen for outpatient follow-up after the discharge, at which point the pleural mass appeared resolved on a chest radiograph, and her peripheral blood eosinophil count (0.09 × 109/L) dropped to the normal range.

Paragonimiasis is a food-borne parasitic disease caused by paragonimus, and there exist more than 50 species of paragonimus all over the world. Paragonimiasis mainly prevails in Asian, African, and South American countries[1]. Paragonimus westermani and Paragonimus skrjabini are dominant species in south China[2]. Paragonimus miracidiums colonize in a suitable snail host and produce numerous cercariae which later leave the snail and penetrate a crab or crayfish, where they grow and transform into metacercariae. After eaten by a suitable human definitive host, metacercariae excyst in the small intestine and penetrate the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. Juvenile worms migrate through the peritoneal cavity, diaphragm, and pleural space to the lungs. The activity of worms in the pleural cavity can cause pleural effusion and thickening. Worms move into the lung parenchyma where they multiply. Encapsulated worms in the lungs produce typical pulmonary paragonimiasis, and the symptoms are cough, chest pain, fatigue, dyspnea, and fever[5]. Histologically, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia and granulomatous inflammation with associated eosinophils are usually present. Lung parenchyma could present serpiginous zones of necrosis, which sometimes extends to the pleural surface. Paragonimus eggs are generally associated with a granulomatous reaction[6]. Serological tests, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and peripheral eosinophilic granulocyte test, are the most effective methods for laboratory diagnosis of paragonimiasis, and the diagnosis can be confirmed based on clinical, radiological, echo-graphical, and cytological findings. However, the clinical findings in paragonimiasis may resemble those of pleu-ropulmonary tuberculosis (TB), pneumonia, bronchitis, or bronchiectasis. Several studies reported paragonimiasis mimicking TB and the cases were misdiagnosed and treated as TB[7,8]. The mass in the pleural cavity that forms after standard treatment as our case can also lead to a misdiagnosis as malignant lesions.

After the treatment of praziquantel recommended by the World Health Organization at a high dose of 75 mg/kg /d (divided into three doses per day) for 2 d, the majority of the patients have a satisfactory result[9]. However, in cases with a lump in the pleural cavity, praziquantel has a poor therapeutic effect and surgical intervention should be implemented. Video-assisted thoracoscopy is a minimally invasive surgical technique that has been increasingly applied in pediatric surgery due to its superiority of reduction of tissue trauma, less postoperative pain, and reduction of hospital stay, and thoracoscopy can be applied either primarily or after the failure of medication and drainage[10]. Early intervention in pleural effusion like our case is essential to prevent the development of the chronic stage. Based on our clinical experience, and the observation that the pleural effusion of our patients is always an exudate that contains abundant scrambled egg-like material, drainage in the exudative stage is hard to drain all the fluid because the fibrous material can block the drainage tube and the fibrous material can lead to fibrous lump formation like our reported case. However, no suggestion of surgical intervention has been recommended for the treatment of paragonimiasis pleural effusion. Therefore, we recommend thoracoscopic intervention when fibrous contents are present on CT scan or chest roentgenogram to avoid later fibrous lump formation. Thanks to the minimal invasion of thoracoscopy, patients can recover quickly and pleural exudate could be removed early and thoroughly, thus reducing the hospital stay and improving the treatment outcomes.

Thoracoscopic intervention should be performed when fibrous contents are present on CT scan or chest roentgenogram to avoid later fibrous lump formation. Diagnose can also be confirmed by finding paragonimus ova in the pleural fluid removed by thoracoscopy. As for why paragonimiasis could cause such a chronic phase, we postulate that this result is related to the species, and more studies should be conducted on this issue.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sugimura H S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Blair D. Paragonimiasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1154:105-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yoshida A, Doanh PN, Maruyama H. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Asia: An update. Acta Trop. 2019;199:105074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cumberlidge N, Rollinson D, Vercruysse J, Tchuem Tchuenté LA, Webster B, Clark PF. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in West and Central Africa: unresolved questions. Parasitology. 2018;145:1748-1757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lane MA, Barsanti MC, Santos CA, Yeung M, Lubner SJ, Weil GJ. Human paragonimiasis in North America following ingestion of raw crayfish. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e55-e61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Doanh PN, Horii Y, Nawa Y. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Vietnam: an update. Korean J Parasitol. 2013;51:621-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boland JM, Pritt BS. Histopathology of parasitic infections of the lung. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:550-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Calvopina M, Romero-Alvarez D, Macias R, Sugiyama H. Severe Pleuropulmonary Paragonimiasis Caused by Paragonimus mexicanus Treated as Tuberculosis in Ecuador. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:97-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lall M, Sahni AK, Rajput AK. Pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis: mimicker of tuberculosis. Pathog Glob Health. 2013;107:40-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oh IJ, Kim YI, Chi SY, Ban HJ, Kwon YS, Kim KS, Kim YC, Kim YH, Seon HJ, Lim SC, Shin HY, Kim SO. Can pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis be cured by only the 1st set of chemotherapy? Intern Med. 2011;50:1365-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bawazir OA. Thoracoscopy in pediatrics: Surgical perspectives. Ann Thorac Med. 2019;14:239-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |