Published online Jan 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.623

Peer-review started: July 12, 2020

First decision: November 26, 2020

Revised: December 2, 2020

Accepted: December 10, 2020

Article in press: December 10, 2020

Published online: January 26, 2021

Processing time: 192 Days and 10.8 Hours

Type 1 sialidosis, also known as cherry-red spot-myoclonus syndrome, is a rare autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder presenting in the second decade of life. The most common symptoms are myoclonus, ataxia and seizure. It is rarely encountered in the Chinese mainland.

A 22-year-old male presented with complaints of progressive myoclonus, ataxia and slurred speech, without visual symptoms; the presenting symptoms began at the age of 15-year-old. Whole exome sequencing revealed two pathogenic heterozygous missense variants [c.239C>T (p.P80L) and c.544A>G (p.S182G) in the neuraminidase 1 (NEU1) gene], both of which have been identified previously in Asian patients with type 1 sialidosis. All three patients identified in Mainland China come from three unrelated families, but all three show the NEU1 mutations p.S182G and p.P80L pathogenic variants. Increasing sialidase activity through chaperones is a promising therapeutic target in sialidosis.

Through retrospective analysis and summarizing the clinical and genetic characteristics of type 1 sialidosis, we hope to raise awareness of lysosomal storage disorders among clinicians and minimize the delay in diagnosis.

Core Tip: Type 1 sialidosis is a rare autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder. Very few cases of this condition have been reported in mainland China, which may be partly attributed to an inadequate awareness of lysosomal storage diseases among neurology physicians. This study reports the clinical and molecular characteristics of a Chinese patient with type 1 sialidosis confirmed by genetic testing. Neuraminidase 1 mutations p.S182G and p.P80L are common pathogenic variants of all three patients identified in Mainland China, coming from three unrelated families.

- Citation: Cao LX, Liu Y, Song ZJ, Zhang BR, Long WY, Zhao GH. Compound heterozygous mutations in the neuraminidase 1 gene in type 1 sialidosis: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(3): 623-631

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i3/623.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.623

Sialidosis is a progressive lysosomal storage disease that exhibits an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, with an incidence of 0.04 in 100000[1]. This condition is caused by mutations in the neuraminidase 1 (NEU1) gene, leading to alpha-N-acetylneuraminidase (sialidase) deficiency and abnormal tissue accumulation and urinary excretion of sialylated oligosaccharides and glycolipids[2]. Sialidosis can be classified into types 1 and 2, according to the clinical presentation. Type I sialidosis has a relatively late onset (predominantly ages 10-30 years) and a milder phenotype[3], whereas type 2 sialidosis is a severe form with earlier onset and is further subdivided into congenital, infantile and juvenile forms, which show abnormalities in utero, within 1 year of birth and after the age of 2 years, respectively[3].

The clinical characteristics of type I sialidosis include myoclonus, seizures, ataxia, visual symptoms and cognition impairment presenting in the second decade of life[4]. This condition is also known as cherry-red spot-myoclonus syndrome[5]. Tibial somatosensory evoked potentials (commonly known as SSEP), suggesting giant cortical potential, in addition to abnormal electroencephalography (commonly referred to as EEG) and brain magnetic resonance imaging (commonly referred to as MRI) provide strong evidence for sialidosis diagnosis[4,6,7]. To date, 55 genetically-confirmed patients have been reported in various regions of the world and more than 30 NEU1 mutations have been shown to be responsible for type 1 sialidosis[6-8].

Here, we describe the clinical manifestations of a 22-year-old man with type 1 sialidosis carrying two known pathogenic missense variants that have been identified previously in Chinese and Japanese patients.

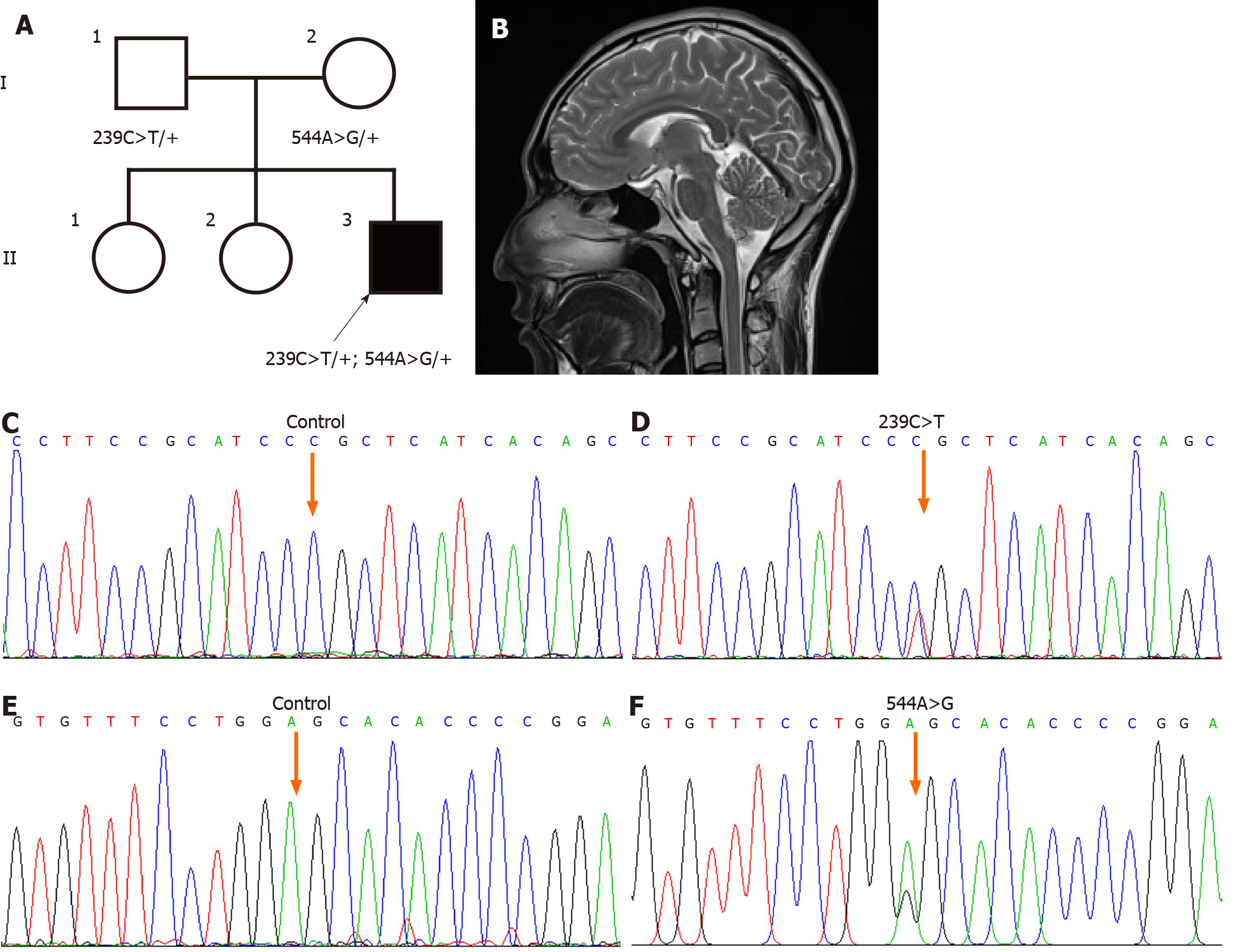

A 22-year-old male (II:3; Figure 1A) from Southwest China was admitted to the Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine to address involuntary movements of the four extremities and dysarthria lasting for several years.

Aged 16 years, the patient experienced involuntary shaking of the bilateral upper limbs, with gradual lower limb involvement over the next few years, resulting in disruption of his walking balance. Three years previously, the patient experienced an inability to speak clearly and fluently and he achieved only a junior middle school education. Despite numerous visits to his doctors, the patient did not obtain a definitive diagnosis nor effective treatment. When he presented to our clinic, he exhibited worsening ataxia and myoclonus resulting in impaired walking ability and difficulties with communication.

The patient had a free previous medical history.

The patient’s parents were in a nonconsanguineous marriage and neither they nor his elder sister complained of the same symptoms.

The neurological examination revealed slurred speech, intention tremor, ataxia, and marked hyperreflexia. His cognition was normal. He had normal eye movement, no nystagmus, and denied visual symptoms, such as blurred vision and visual field defects.

His routine laboratory test results were unremarkable and there were no abnormalities in his EEG. Electromyography and nerve conduction velocity examination of the patient indicated reduced motor nerve conduction velocity and prolonged motor latency in the left peroneal nerve.

Cranial MRI showed slight atrophy of the bilateral cerebellum (Figure 1B). Fundus photographs of both eyes showed absence of a cherry-red spot (not shown).

The diagnosis of type 1 sialidosis was confirmed by identification of compound heterozygous known mutations in the NEU1 gene: c.239C>T (p.Pro80Leu) and c.544A>G (p.Ser182Gly).

The patient was treated with 5 mg of buspirone and 30 mg of idebenone three times per day.

The patient did not continue to take medicine not long after he was discharged from the hospital. Six months after his discharge, involuntary shaking of the four extremities and dysarthria persisted without significant improvement or aggravation.

Type 1 sialidosis is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder. Here, we describe a 22-year-old male who exhibited cerebellar ataxia, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, slurred speech, and mild cerebellar atrophy. The diagnosis of type 1 sialidosis was confirmed by identification of compound heterozygous known mutations in the NEU1 gene, namely c.239C>T (p.Pro80Leu) and c.544A>G (p.Ser182Gly). Very few cases of this condition have been reported in mainland China, which may be partly attributed to an inadequate awareness of lysosomal storage diseases among neurology physicians. In recent years, the widespread use of next-generation sequencing technologies in clinical settings has improved the accuracy and sensitivity of diagnosis of lysosomal storage diseases.

Previous reports indicate that myoclonus is the most common symptom of type 1 sialidosis and was detected in almost all the genetically diagnosed patients[4,7,9]. Overall, 88.3% of patients present with ataxia and 72.5% with seizures[8]. Visual disturbances, such as blurred vision and visual field deficits, occur in only 68.4% of all cases[8]. Although type 1 sialidosis is also known as cherry-red spot-myoclonus syndrome, is noteworthy that this feature was observed in less than half of all the reported patients, indicating that this is not an accurate naming of this disease[10]. Furthermore, cherry-red spots are seen more frequently in Caucasian patients than in Asian patients (61.1% vs 40.7%)[8], suggesting that this feature should not be listed as an indispensable sign of type 1 sialidosis diagnosis, especially in Asian patients. The possible reasons for this lack of cherry-red spots include late appearance, residual enzymatic activity, and potential effects of various mutations[11,12]. Macular cherry-red spot is caused by deposition of material in the ganglion cells of the macula in the retina. Because ganglion cells are several layers thick in this area and absent from the fovea, the fovea remains relatively transparent and contrasts with the surrounding opaque retina[13]. Moreover, prolonged visual evoked potential latency and giant cortical potential SSEP are also helpful for early diagnosis[6,8,14]. In neuroimaging, diffuse brain atrophy (particularly the cerebellum) can be evident in the advanced stage of type 1 sialidosis[15]. In addition, accumulation of sialyloligosaccharides can be observed in the central nervous system of sialidosis patients by pathological examination[15].

To date, more than 30 NEU1 mutations have been identified as responsible for type 1 sialidosis (Table 1)[4,7,8,11-27]. Missense variants are the most common pathogenic mutations, and few exonic duplications or deletions have been reported[11]. The symptoms and severity of the disease are closely related to the type of NEU1 variants and the levels of residual enzyme activity[16]. The missense mutation c.544A>G (p.S182G) was previously reported to be pathogenic and is a common missense mutation in the Taiwanese population[4,8]. Lai et al[4] reported that macular cherry-red spots were present in three of 17 Taiwanese patients with type 1 sialidosis who carried the NEU1 c.544A>G (p.S182G) mutation. Patients harboring the Ser182Gly mutation may have relatively high enzymatic activity (~40% of normal) compared with other known mutations (for instance, Phe260Tyr and Leu270Phe mutants showed 10%-20% of normal enzymatic activity), and they may have a slower rate of lysosomal sialic acid accumulation in retinal cells, resulting in moderate symptoms and absence of macular cherry-red spots[28]; this feature is consistent with our patient. A review of all the type I sialidosis cases reported in the Chinese population (Table 2[4,8,20,29-31]) revealed that p.S182G and p.P80L are the common pathogenic variants of all three patients identified in Mainland China from three unrelated families[29,30]. Unlike the patient in this study, however, the other two cases previously reported in China had visual symptoms and cherry-red spots.

| Mutation | Nucleotide change | Exon | Origin | Ref. |

| R6Qfs*21 | c.15_16del | 1 | Korean | Ahn et al[7] |

| V54M | c.160G>A | 1 | German | Bonten et al[17] |

| Q55X | c.163C>T | 1 | Taiwanese | Lai et al[4] |

| S67I | c.200G>T | 2 | Italian | Canafoglia et al[18] |

| P80L | c.239C>T | 2 | Japanese, Chinese | Sekijima et al[15] |

| A106_G118 del | c.314_352del | 2 | Taiwanese | Fan et al[8] |

| L111P | c.332T>C | 2 | French | Seyrantepe et al[11] |

| D135N | c.403G>A | 3 | Japanese | Sekijima et al[15] |

| G136E | c.407G>A | 3 | French | Seyrantepe et al[11] |

| D177V | c.530A>T | 3 | Italian | Hu et al[20] |

| S182G | c.544A>G | 3 | Chinese, Taiwanese | Lai et al[4], Fan et al[8], Mohammad et al[12], Bonten et al[17], and Hu et al[20] |

| Q207X | c.619C>T | 3 | Taiwanese | Hu et al[20] |

| E209Sfs*94 | c.625delG | 3 | Turkish | Gultekin et al[21] |

| P210L | c.629C>T | 3 | Ecuadorian | Aravindhan et al[14] |

| V217M | c.649G>A | 4 | Japanese | Naganawa et al[16] |

| G218A | c.654G>A | 4 | African-American | Bonten et al[17] |

| G219A | c.656G>A | 4 | African, American | Bonten et al[17] |

| G227R | c.679G>A | 4 | Greek, Italian, East-Asian, Dutch | Mohammad et al[12], Bonten et al[17], Canafoglia et al[18], Schene et al[22] |

| L231H | c.692T>A | 4 | African | Bonten et al[17] |

| S233R | c.699C>A | 4 | German | Mütze et al[23] |

| D234N | c.700G>A | 4 | Portuguese | Sobral et al[13] |

| G243R | c.727G>A | 4 | Japanese | Naganawa et al[16] |

| G248C | c.742G>T | 4 | Indian | Gowda et al[24] |

| Y268C | c.803A>G | 5 | German | Mütze et al[23] |

| V275A | c.824T>C | 5 | French | Seyrantepe et al[11] |

| R280Q | c.839G>A | 5 | Italian | Caciotti et al[19] |

| R294S, R294C | c.880C>A, c.880C>T | 5 | African, Indian, Hispanic | Bonten et al[17] |

| R305C | c.913C>T | 5 | Italian | Canafoglia et al[18] |

| D310N | c.928G>A | 5 | Turkish, Korean | Ahn et al[7], Gultekin et al[21] |

| P316S | c.946C>T | 5 | Japanese | Itoh et al[25] |

| A319V | c.956C>T | 5 | Taiwanese | Lai et al[4] |

| G328S | c.982G>A | 5 | Italian | Palmeri et al[26] |

| H337R | c.1010A>G | 5 | Italian | Caciotti et al[19] |

| R341X | c.1021C>T | 5 | Portuguese | Sobral et al[13] |

| T345I | c.1034C>T | 6 | Czech | Seyrantepe et al[11] |

| E377X | c.1129G>T | 6 | German | Canafoglia et al[18] |

| N398Tfs*90 | c.1191delG | 6 | Indian | Ranganath et al[27] |

| H399_Y400dup | c.1195_1200dup | 6 | Dutch | Schene et al[22] |

| Family | Case | Geographical distribution | Mutation 1 | Mutation 2 | Age at onset, yr | Age at diagnosis, yr | Symptoms (presenting age) | Cherry-red spot | Ref. |

| 1 | 1 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 27 | 42 | S (27), M (28), A (29) | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 1 | 2 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 19 | 34 | S (19), M (19), A (19), V (29), SD | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 2 | 3 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 14 | 39 | M (14), S (14), V (14), A (16), SD | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 2 | 4 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 26 | 36 | V (26), M (27), A (27), SD | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 3 | 5 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 16 | 31 | M (16), A (17), V (19), S (21) | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 3 | 6 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 12 | 29 | M (12), A (13), S (16), V (18) | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 4 | 7 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 20 | 51 | M (20), Fall (20), S (26), SD | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 4 | 8 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 33 | 45 | V (33), M (34), A (34), S (37) | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 5 | 9 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 20 | 39 | M (20), A (21), SD | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 5 | 10 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 15 | 35 | M (15), A (15), V (25), SD | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 6 | 11 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 18 | 42 | M (18), Fall (18), S (20), A (24), V (28) | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 7 | 12 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 28 | 47 | S (28), M (29), A (29), V (39) | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 8 | 13 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.A319V | 14 | 25 | M (14), A (19), S (25), V (20), SD | 1 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 9 | 14 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.Q55X | 12 | 27 | M (12), A (14), V (14), S (15) | 1 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 10 | 15 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 19 | 49 | M (19), A (24), V (29) | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 11 | 16 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 18 | 33 | V (18), M (20), A (20), S (33), SD | 0 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 12 | 17 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.S182G | 14 | 43 | V (14), M (31), A (32), S (40) | 1 | Lai et al[4], 2009 |

| 13 | 18 | Mainland | p.S182G | p.P80L | 11 | 17 | V (11), S (15), M (15), A (15) | 1 | Baojingzi et al[30], 2015 |

| 14 | 19 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.Gln207* | 12 | 15 | S (12), A (12), M (12), dysarthria | 1 | Hu et al[20], 2018 |

| 15 | 20 | Taiwan | p.S182G | p.A106_G118 deletion | 13 | 16 | M (13), A | 0 | Fan et al[8], 2020 |

| 16 | 21 | Mainland | p.S182G | p.P80L | 10 | 12 | Limb pain (10), Fall (10), M (11), V (11), S (11) | 1 | Liu et al[29], 2019 |

| 17 | 22 | China | p.S182G | p.S182G | NA | 24 | M, dysphagia | NA | Carey et al[31], 1997 |

| 18 | 23 | Mainland | p.S182G | p.P80L | 16 | 22 | M (16), A (19) | 0 | Current study |

Currently, available therapies for sialidosis are limited to symptom management. The myoclonus can be alleviated by drugs such as clonazepam and valproic acid, as well as piracetam in some cases. The most common type of seizures in type 1 sialidosis are generalized tonic-clonic seizure and myoclonic seizures, which can be significantly controlled within 1 year by anti-epileptic drugs, with seizures subsequently occurring at low frequency[4]. A longitudinal study revealed that both of these primary symptoms deteriorate during the first 5 years after onset and then remain stable, suggesting a more rapid progression in the early stages of this disorder[4]. Further longitudinal studies of patients with different mutations and geographical origin are needed to verify this pattern. The limitation of this case report is the absence of long-term follow-up and reexamination of the patient to assess the progress of the disease.

The underlying pathological mechanism of type 1 sialidosis is still unclear, and finding specific therapeutic approaches remains a significant challenge. Studies have implicated proteosomal regulation as a potential therapeutic target. Proteasomal inhibitors (e.g., MG132) combined with chemical chaperones (e.g., celastrol) have been shown to rescue misfolded sialidase and increase enzyme expression[32]. In addition, protective protein/cathepsin A (known as PPCA)-chaperone-mediated gene therapy has shown positive effects in protecting against severe phenotypes in a mouse model of type 1 sialidosis carrying a NEU1 variant (a V54M amino acid substitution). Enzyme activity was successfully increased in the systemic tissues of mice following injection with a liver-tropic recombinant AAV2/8 vector expressing PPCA, which is a NEU1 binding chaperone that maintains lysosomal compartmentalization, stability and catalytic activation[33]. These results provide promising evidence that increasing sialidase activity through chaperones is a promising therapeutic target in sialidosis.

Type 1 sialidosis is a rare autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder. Very few cases of this condition have been reported in mainland China, which may be partly attributed to an inadequate awareness of lysosomal storage diseases among neurology physicians. NEU1 mutations p.S182G and p.P80L are the shared pathogenic variants among all three patients identified in Mainland China, although from three unrelated families. Increasing sialidase activity through chaperones is a promising therapeutic target in sialidosis.

We are thankful to the patients who agreed to participate in this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gingras M S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Arora V, Setia N, Dalal A, Vanaja MC, Gupta D, Razdan T, Phadke SR, Saxena R, Rohtagi A, Verma IC, Puri RD. Sialidosis type II: Expansion of phenotypic spectrum and identification of a common mutation in seven patients. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2020;22:100561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pshezhetsky AV, Richard C, Michaud L, Igdoura S, Wang S, Elsliger MA, Qu J, Leclerc D, Gravel R, Dallaire L, Potier M. Cloning, expression and chromosomal mapping of human lysosomal sialidase and characterization of mutations in sialidosis. Nat Genet. 1997;15:316-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Khan A, Sergi C. Sialidosis: A Review of Morphology and Molecular Biology of a Rare Pediatric Disorder. Diagnostics (Basel). 2018;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lai SC, Chen RS, Wu Chou YH, Chang HC, Kao LY, Huang YZ, Weng YH, Chen JK, Hwu WL, Lu CS. A longitudinal study of Taiwanese sialidosis type 1: an insight into the concept of cherry-red spot myoclonus syndrome. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:912-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Till JS, Roach ES, Burton BK. Sialidosis (neuraminidase deficiency) types I and II: neuro-ophthalmic manifestations. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1987;7:40-44. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bhoi SK, Jha M, Naik S, Palo GD. Sialidosis Type 1: Giant SSEP and Novel Mutation. Indian J Pediatr. 2019;86:760-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ahn JH, Kim AR, Lee C, Kim NKD, Kim NS, Park WY, Kim M, Youn J, Cho JW, Kim JS. Type 1 Sialidosis Patient With a Novel Deletion Mutation in the NEU1 Gene: Case Report and Literature Review. Cerebellum. 2019;18:659-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fan SP, Lee NC, Lin CH. Clinical and electrophysiological characteristics of a type 1 sialidosis patient with a novel deletion mutation in NEU1 gene. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119:406-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vieira de Rezende Pinto WB, Sgobbi de Souza PV, Pedroso JL, Barsottini OG. Variable phenotype and severity of sialidosis expressed in two siblings presenting with ataxia and macular cherry-red spots. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:1327-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bou Ghannam AS, Mehner LC, Pelak VS. Sialidosis Type 1 Without Cherry-Red Spot. J Neuroophthalmol. 2019;39:388-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Seyrantepe V, Poupetova H, Froissart R, Zabot MT, Maire I, Pshezhetsky AV. Molecular pathology of NEU1 gene in sialidosis. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:343-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mohammad AN, Bruno KA, Hines S, Atwal PS. Type 1 sialidosis presenting with ataxia, seizures and myoclonus with no visual involvement. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2018;15:11-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sobral I, Cachulo Mda L, Figueira J, Silva R. Sialidosis type I: ophthalmological findings. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aravindhan A, Veerapandiyan A, Earley C, Thulasi V, Kresge C, Kornitzer J. Child Neurology: Type 1 sialidosis due to a novel mutation in NEU1 gene. Neurology. 2018;90:622-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sekijima Y, Nakamura K, Kishida D, Narita A, Adachi K, Ohno K, Nanba E, Ikeda S. Clinical and serial MRI findings of a sialidosis type I patient with a novel missense mutation in the NEU1 gene. Intern Med. 2013;52:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Naganawa Y, Itoh K, Shimmoto M, Takiguchi K, Doi H, Nishizawa Y, Kobayashi T, Kamei S, Lukong KE, Pshezhetsky AV, Sakuraba H. Molecular and structural studies of Japanese patients with sialidosis type 1. J Hum Genet. 2000;45:241-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bonten EJ, Arts WF, Beck M, Covanis A, Donati MA, Parini R, Zammarchi E, d'Azzo A. Novel mutations in lysosomal neuraminidase identify functional domains and determine clinical severity in sialidosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2715-2725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Canafoglia L, Robbiano A, Pareyson D, Panzica F, Nanetti L, Giovagnoli AR, Venerando A, Gellera C, Franceschetti S, Zara F. Expanding sialidosis spectrum by genome-wide screening: NEU1 mutations in adult-onset myoclonus. Neurology. 2014;82:2003-2006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Caciotti A, Melani F, Tonin R, Cellai L, Catarzi S, Procopio E, Chilleri C, Mavridou I, Michelakakis H, Fioravanti A, d'Azzo A, Guerrini R, Morrone A. Type I sialidosis, a normosomatic lysosomal disease, in the differential diagnosis of late-onset ataxia and myoclonus: An overview. Mol Genet Metab. 2020;129:47-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hu SC, Hung KL, Chen HJ, Lee WT. Seizure remission and improvement of neurological function in sialidosis with perampanel therapy. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2018;10:32-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gultekin M, Bayramov R, Karaca C, Acer N. Sialidosis type I presenting with a novel mutation and advanced neuroimaging features. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2018;23:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schene IF, Kalinina Ayuso V, de Sain-van der Velden M, van Gassen KL, Cuppen I, van Hasselt PM, Visser G. Pitfalls in Diagnosing Neuraminidase Deficiency: Psychosomatics and Normal Sialic Acid Excretion. JIMD Rep. 2016;25:9-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mütze U, Bürger F, Hoffmann J, Tegetmeyer H, Heichel J, Nickel P, Lemke JR, Syrbe S, Beblo S. Multigene panel next generation sequencing in a patient with cherry red macular spot: Identification of two novel mutations in NEU1 gene causing sialidosis type I associated with mild to unspecific biochemical and enzymatic findings. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2017;10:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gowda VK, Srinivasan VM, Benakappa N, Benakappa A. Sialidosis Type 1 with a Novel Mutation in the Neuraminidase-1 (NEU1) Gene. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84:403-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Itoh K, Naganawa Y, Matsuzawa F, Aikawa S, Doi H, Sasagasako N, Yamada T, Kira J, Kobayashi T, Pshezhetsky AV, Sakuraba H. Novel missense mutations in the human lysosomal sialidase gene in sialidosis patients and prediction of structural alterations of mutant enzymes. J Hum Genet. 2002;47:29-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Palmeri S, Villanova M, Malandrini A, van Diggelen OP, Huijmans JG, Ceuterick C, Rufa A, DeFalco D, Ciacci G, Martin JJ, Guazzi G. Type I sialidosis: a clinical, biochemical and neuroradiological study. Eur Neurol. 2000;43:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ranganath P, Sharma V, Danda S, Nandineni MR, Dalal AB. Novel mutations in the neuraminidase-1 (NEU1) gene in two patients of sialidosis in India. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136:1048-1050. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Lukong KE, Elsliger MA, Chang Y, Richard C, Thomas G, Carey W, Tylki-Szymanska A, Czartoryska B, Buchholz T, Criado GR, Palmeri S, Pshezhetsky AV. Characterization of the sialidase molecular defects in sialidosis patients suggests the structural organization of the lysosomal multienzyme complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1075-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Liu MM, Shao XQ, Li ZM, Lv RJ, Wang Q, Cui T. Sialidosis: a case report. Nao Yu Shenjing Jibing Zazhi. 2019;27:148-152. |

| 30. | Baojingzi Z, Chao Q, Sushan L, Qiuqiong D, Chongbo Z, Jiahong L. Cherry-red Spot:A Case Report of Sialidosis I and Literature Review. Zhongguo Linchuang Shenjing Kexue Zazhi. 2015;1:115-121. |

| 31. | 31 Carey WF, Fletcher JM, Wong MC. A case of sialidosis with unusual results. In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress of Inborn Errors of Metabolism. Vienna, Austria 1997; 104. |

| 32. | O'Leary EM, Igdoura SA. The therapeutic potential of pharmacological chaperones and proteosomal inhibitors, Celastrol and MG132 in the treatment of sialidosis. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;107:173-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bonten EJ, Yogalingam G, Hu H, Gomero E, van de Vlekkert D, d'Azzo A. Chaperone-mediated gene therapy with recombinant AAV-PPCA in a new mouse model of type I sialidosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1784-1792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |