Published online Jan 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.607

Peer-review started: May 23, 2020

First decision: November 26, 2020

Revised: November 30, 2020

Accepted: December 10, 2020

Article in press: December 10, 2020

Published online: January 26, 2021

Processing time: 242 Days and 6.5 Hours

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) is a rare malignant tumor of the skin that is commonly found on the face. It grows slowly and has a low mortality rate. However, for various reasons, including strong histological invasiveness, clinical inexperience and inadequate procedure design, immediate or permanent facial deformity may occur after surgical operations.

This article describes a middle-aged female artist who was diagnosed with MAC on the left upper lip. She declined the recommended treatment plan, which included two-stage reconstruction, skin grafting, or surgery that could have resulted in obvious facial dysfunction or esthetic deformity. We accurately designed a personalized procedure involving a “jigsaw puzzle advancement flap” for the patient based on the lesion location and the estimated area of skin loss. The procedure was successful; both pathological R0 resection and immediate and long-term esthetic reconstruction effects were achieved.

This study suggests that when treating facial MAC or other skin malignancies, a surgical team should have sufficient plastic surgery-related knowledge and skills. An optimal surgical plan for an individual is needed to achieve good facial esthetics and functional recovery and shorten the treatment course.

Core Tip: Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a rare skin malignancy, which has a low mortality rate. In this study, we offered a new idea in treating a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma on the left upper lip and obtained satisfying esthetic reconstruction effect.

- Citation: Xiao YD, Zhang MZ, Zeng A. Facial microcystic adnexal carcinoma — treatment with a “jigsaw puzzle” advancement flap and immediate esthetic reconstruction: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(3): 607-613

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i3/607.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.607

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) is a rare skin malignancy that was first reported by Goldstein et al[1] in 1982. Mostly occurring as a single lesion on the face, MAC grows slowly and has a low mortality rate. The major treatment approach is radical resection. The postoperative recurrence rate is high because MAC exhibits irregular invasive growth and is difficult to pathologically diagnose. Surgical treatment often leads to immediate or permanent facial deformities, which seriously affect patients’ quality of life and psychological health. Based on our successful experience treating a patient with MAC on the left upper lip, we present a new idea to address the importance of adequate pre-planning before surgery and esthetic reconstruction of body surfaces in the context of MAC.

A 60-year-old female presented with complaints of a slowly growing mass on her left upper lip for 8 years.

The mass was soybean-sized and did not cause any specific discomfort. One month earlier, this patient considered the mass might be continuously growing and decided to remove it. She went to another hospital and was diagnosed with pigmented nevus. The mass was removed without any extended resection and the wound was directly closed. The patient recovered well and removed the sutures on time with no infection or other complications occurring. Postoperative pathological and immunohistochemical diagnosis indicated skin MAC with positive lateral and basal margins.

The patient had a history of surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma and denied any history of postoperative radiotherapy. No other positive history of past illness was offered.

This patient declared no smoking or alcohol history and any other noteworthy family medical history.

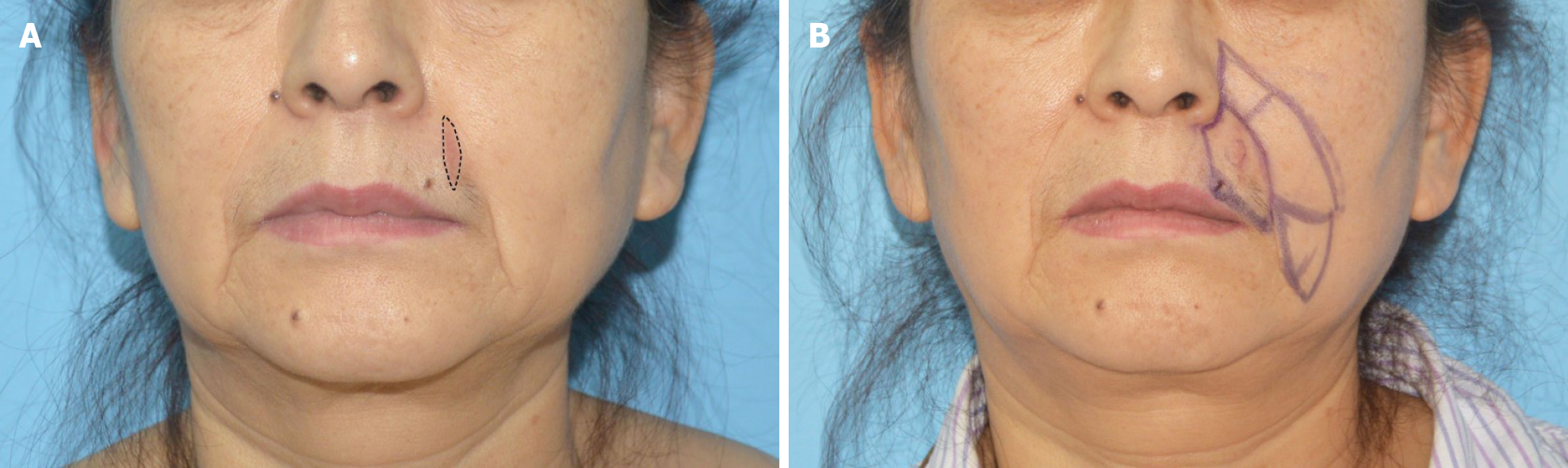

Physical examination on admission showed a light red scar on the left upper lip with a length of approximately 3 cm (Figure 1A).

According to pathological and immunohistochemical diagnosis, this patient was diagnosed as MAC on left upper lip with positive lateral and basal margins.

Considering the rareness of MAC in Asian populations, we recommended Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or extended surgical resection as a treatment plan based on existing treatment principles. All these surgical procedures included two-stage reconstruction and skin grafting, and may have caused obvious facial dysfunction or esthetic deformity. The patient consented to surgery; however, because she was an artist and had high expectations for postoperative facial appearance, she declined the original surgical plan. These preferences required us to deeply understand the facial skin defect caused by surgery and fully control the facial appearance after reconstruction.

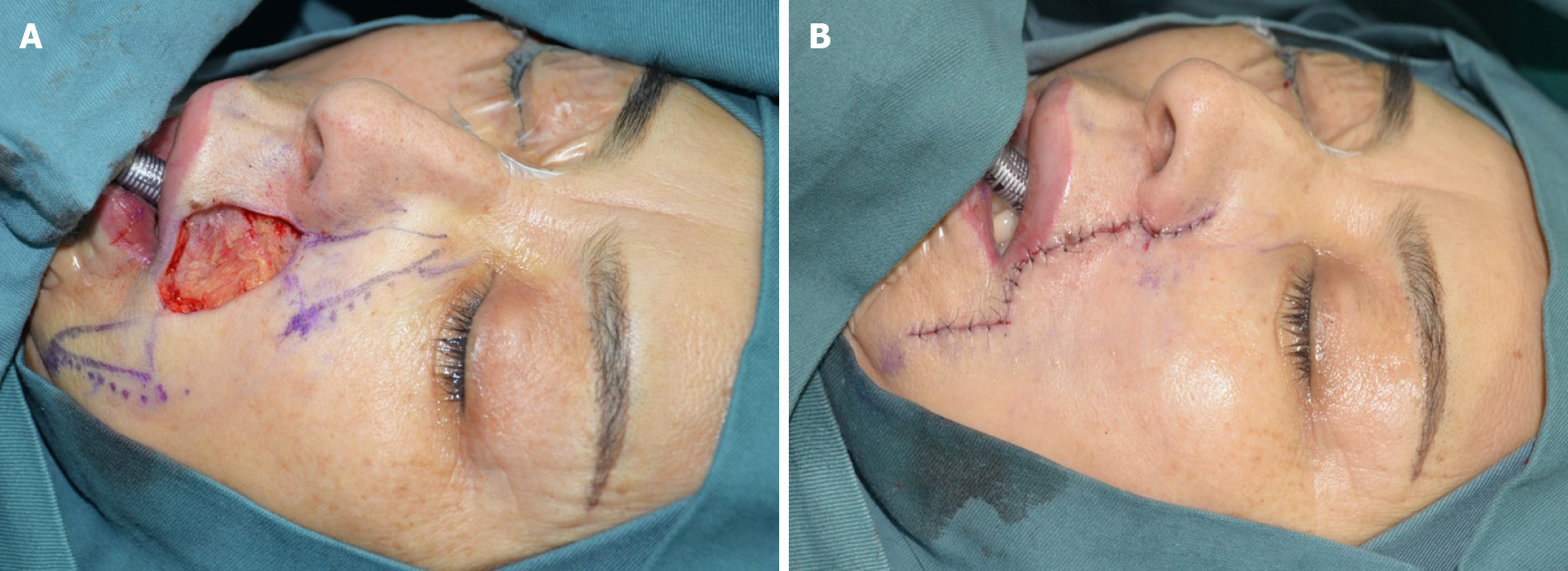

To this end, we referred to the “jigsaw puzzle advancement flap” concept proposed by Paradisi et al[2] and performed one-stage reconstruction of the lateral subunit of the patient’s left upper lip (Figure 1B). To completely remove the mass, an incision was made along a marked line 1.5 cm from the edge of the original surgical scar, superior to the lower edge of the alae nasi and inferior to the vermilion border, with depth to the deep surface of the orbicularis oris muscle. Intraoperative frozen section indicated negative cutting margins. In accordance with our plan, we designed and used a puzzle advancement flap for repair of the dog-ear deformity. The wound was then closed with layered intermittent sutures (Figure 2).

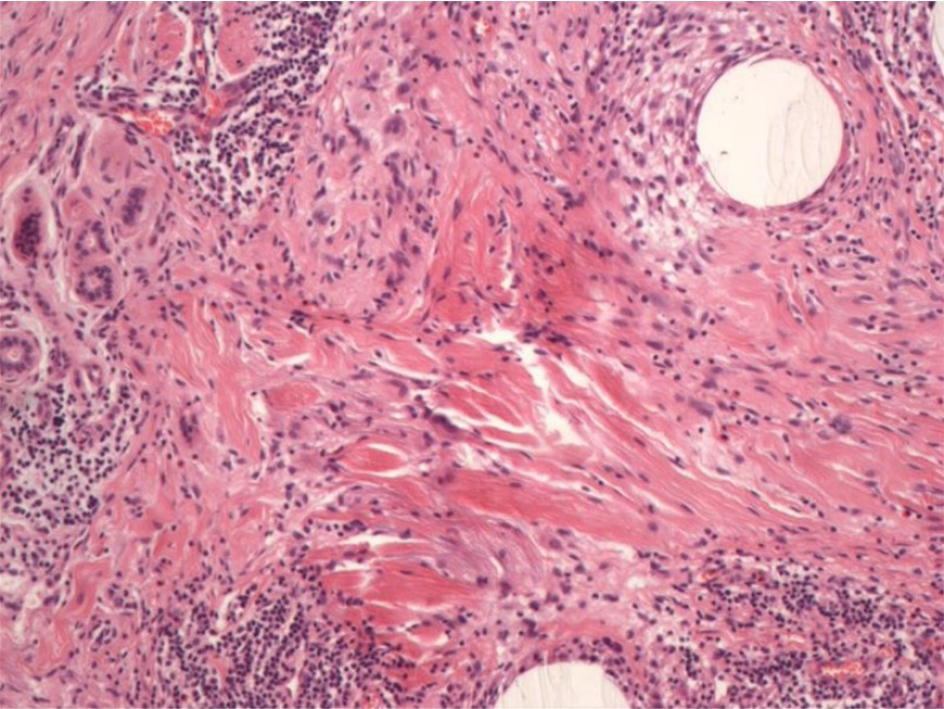

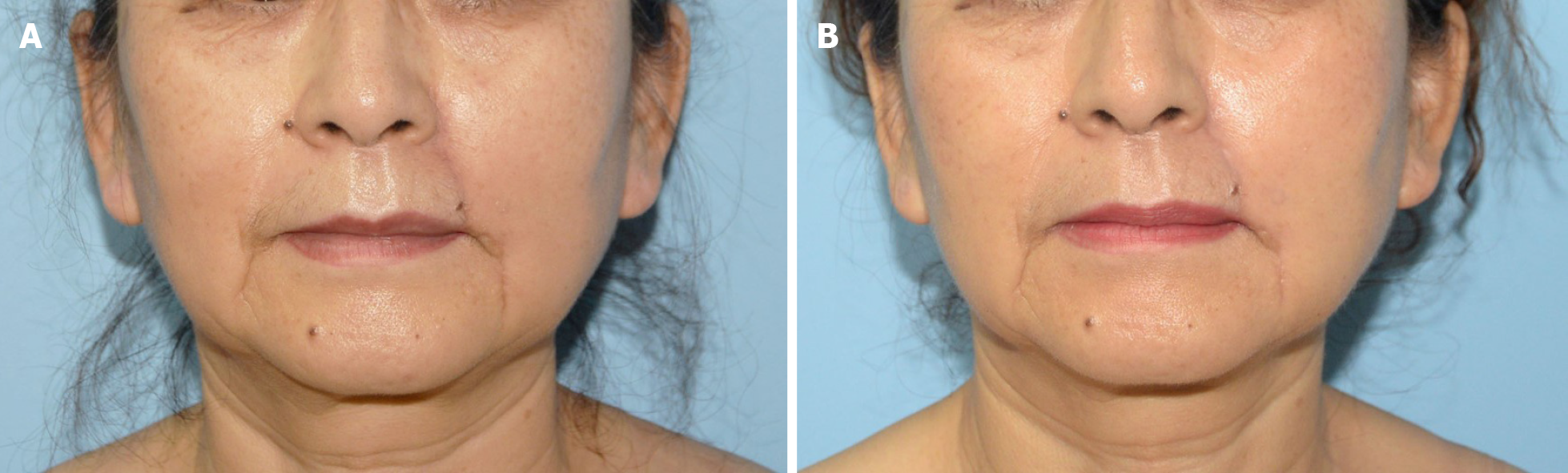

The operation went smoothly, and the patient recovered and was discharged. Postoperative paraffin-embedded sections and immunohistochemical results confirmed the diagnosis of MAC and showed negative resection margins (Figure 3). Examinations immediately after surgery and at 1 year of follow-up showed that the surgical incision healed well without obvious scarring. The bilateral nasolabial folds and the philtrum were essentially symmetrical and exhibited good facial sensation and movement function (Figure 4). The patient was satisfied with the effectiveness of treatment.

MAC is a rare skin malignant tumor with slow growth but locally asymmetric invasion. Reports have indicated an incidence of MAC of approximately 16-65 per million individuals[3-6]. Moreover, 90% of reported cases of MAC have involved middle-aged Caucasians, although occasional cases involving patients of African or Asian descent have been reported[7-9]. Because MAC appears to be related to ultraviolet radiation exposure, lesions are found in the head and neck regions in 74% of patients[3,5,9]. Particularly common locations for this tumor include the cheeks, nasolabial folds, neck, scalp, and periorbital areas. In a few cases, MAC has been detected in the breasts or axillary fossa[4,7,10]. Diagnosis of MAC is mainly based on full-thickness skin pathological biopsy. However, clinical and pathological misdiagnosis rates are high. It is difficult to confirm a diagnosis of MAC using frozen sections. Moreover, common pathological misdiagnoses include folliculitis, eccrine syringoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and sebaceous gland carcinoma. The misdiagnosis rate is as high as 27%-53%, and the final diagnosis needs to be determined via pathology combined with immunohistochemistry after surgery[3,5,7,11,12]. The course of this lesion may be as long as 30 years due to its insidious onset and slow progression. Except for the numbness and burning caused by perineural invasion, MAC is generally not associated with specific clinical discomfort[13,14]. Moreover, the mortality rate for this malignant tumor is extremely low, and almost no distant metastases have been reported[4,15,16].

Based on the primary characteristics of this tumor that have been described above, MAC should be classified as a relatively “mild and friendly” malignant tumor. However, the situation is completely different with respect to treatment. Most reports show that MAC is not sensitive to chemotherapy. Although radiotherapy can reduce tumor burden, it cannot achieve clinical cure and has the risk of causing MAC to become more aggressive. Therefore, it is not recommended[3,7,8]. Radical resection is the most definitive and effective method for treating MAC, and the main options include extensive surgical resection or Mohs MMS (with MMS being the preferred surgery for periorbital MAC because of the tumor’s perineural invasion). The recurrence rate of MMS is relatively low. This phenomenon may be related to the limited duration of postoperative follow-up, as it has been reported that MAC can recur up to 30 years after surgery[3,5,15,17]. MAC is typically solitary, and the average size of the lesion under naked-eye inspection is less than 2 cm. These characteristics lead both doctors and patients to underestimate the difficulty of surgery[3]. Most patients seek medical attention due to concern about cosmetic facial appearance rather than malignant tumors. Surgeons do not accurately determine the region of extensive resection prior to surgery. These facts are associated with final treatment effectiveness. It has been reported that the actual full-thickness skin defect after MMS is approximately 4 times the size of the original lesion. The wound that remains after extensive resection or MMS needs to be closed using local flaps, myocutaneous flaps, or skin grafts. Insufficient preoperative estimates or inexperienced surgeons (who are usually not plastic surgeons) may cause facial disfigurement that requires a multiple-stage procedure for improvement[8,13,14,18].

We believe that a well-prepared surgical plan can not only greatly shorten the course of treatment and achieve better facial esthetics and functional recovery but also allow surgeons to be more comfortable during preoperative communication with patients and establish better relationships between doctors and patients. Unfortunately, to date, no preoperative design for treating MAC, which is commonly found on the face and is associated with medical disfigurement, has been reported. The rarity of the disease itself and the high misdiagnosis rate limit the development of scientific research, and the unexplored nature of the interdisciplinary field of dermatology, pathology, and plastic surgery is the fundamental cause of the slow progress of research on surgery for facial MAC. In fact, in the field of plastic surgery alone, the introduction of reconstruction methods for facial defects at various positions has been extensively reported. In terms of the left upper lip lesion described in this article, Menick recommended that the corresponding anatomical subunit (i.e. the lateral subunit of the upper lip) should be reconstructed after extended resection to meet the patient’s functional and esthetic needs[19]. Burget et al[20] suggested that the medial edge of the surgical incision should not be close to the philtrum and discouraged the use of a rotating flap of the cheek that would cause significant scarring and differences in skin color[21]. Paradisi proposed a puzzle advancement flap that can be used to effectively avoid having the nasolabial folds disappear or become shallow after reconstruction of the lateral subunit of the upper lip in one-stage surgery[2]. As plastic surgeons, based on fully studying and understanding the treatment principles for the rare tumor MAC, we respected the patient’s high expectations for the esthetic effect of surgery in the current case. Using the puzzle advancement flap as the template, we designed and successfully performed the subtle surgery described here and achieved results that were satisfactory to both the surgeons and the patient.

Furthermore, in the treatment of MAC and other types of skin malignancies, many doctors have focused excessively on the radical effect of resection but ignored the importance of body surface function or esthetic reconstruction after resection. It is important to know that most skin malignancies have a low mortality rate; therefore, an operation that is an “esthetic failure” may result in an ugly or deformed appearance that affects the patient’s entire life. With this consideration in mind, we would propose that before performing surgery on patients with various skin malignancies, particularly patients with facial skin malignancies, surgeons should have sufficient plastic surgery-related knowledge and skills or should request a consultation with a plastic surgeon to jointly develop a “better” surgical plan, even if this proposed treatment is not necessarily the “best” surgical plan. This approach would ensure that surgeons and patients fight together to win a well-prepared battle against such malignancies.

MAC is a rare skin malignant tumor which grows slowly and has a low mortality rate. Most patients with skin malignancies may not only desire treatment, but also a satisfying appearance. In this case, we would suggest plastic surgery-related knowledge or consultation with a plastic surgeon would help surgeons and patients to obtain satisfying post-operative effect.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, general and internal

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ferreira GSA, Okajima H S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Paradisi A, Sonego G, Ricci F, Abeni D. Reconstruction of a Lateral Upper Lip Defect. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:291-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boos MD, Elenitsas R, Seykora J, Lehrer MS, Miller CJ, Sobanko J. Benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations adjacent to a microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a tumor mimic with significant patient implications. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:174-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ceballos PI, Penneys NS, Cohen BH. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a case showing eccrine duct differentiation. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:1236-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aslam A. Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma and a Summary of Other Rare Malignant Adnexal Tumours. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rustemeyer J, Zwerger S, Pörksen M, Junker K. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the upper lip misdiagnosed benign desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;17:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brent AJ, Deol SS, Vaidhyanath R, Saldanha G, Sampath R. A case and literature review of orbital microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Orbit. 2018;37:472-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gordon S, Fischer C, Martin A, Rosman IS, Council ML. Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma: A Review of the Literature. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1012-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Diamantis SA, Marks VJ. Mohs micrographic surgery in the treatment of microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:185-190, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yavuzer R, Boyaci M, Sari A, Ataoğlu O. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the breast: a very rare breast skin tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1092-1094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ongenae KC, Verhaegh ME, Vermeulen AH, Naeyaert JM. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an uncommon tumor with debatable origin. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:979-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mukherjee B, Subramaniam N, Kumar K, Nivean PD. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the orbit mimicking pagetoid sebaceous gland carcinoma. Orbit. 2018;37:235-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Abbate M, Zeitouni NC, Seyler M, Hicks W, Loree T, Cheney RT. Clinical course, risk factors, and treatment of microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a short series report. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1035-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fischer S, Breuninger H, Metzler G, Hoffmann J. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an often misdiagnosed, locally aggressive growing skin tumor. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Carroll P, Goldstein GD, Brown CW Jr. Metastatic microcystic adnexal carcinoma in an immunocompromised patient. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:531-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Eisen DB, Zloty D. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma involving a large portion of the face: when is surgery not reasonable? Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1472-7; discussion 1478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Burns MK, Chen SP, Goldberg LH. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Ten cases treated by Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:429-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim LH, Teston L, Sasani S, Henderson C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: successful management of a large scalp lesion. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2014;48:158-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Menick FJ. Principles and Planning in Nasal and Facial Reconstruction: Making a Normal Face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:1033e-1047e. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Burget GC, Hsiao YC. Nasolabial rotation flaps based on the upper lateral lip subunit for superficial and large defects of the upper lateral lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:556-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Salibian AA, Zide BM. Elegance in Upper Lip Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:572-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |