Published online Oct 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8537

Peer-review started: May 6, 2021

First decision: June 6, 2021

Revised: June 19, 2021

Accepted: August 6, 2021

Article in press: August 6, 2021

Published online: October 6, 2021

Processing time: 144 Days and 23.7 Hours

Necrotizing fasciitis is a fulminant necrotizing soft tissue disease with a high fatality rate. It always starts with impact on the deep fascia rapidly and might result in secondary necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue, fascia, and muscle. Thus, timely and multiple surgical operations are needed for the treatment. Meanwhile, the damage of skin and soft tissue caused by multiple surgical operations may require dermatoplasty and other treatments as a consequence.

Here, we report a case of 50-year-old male patient who was admitted to our hospital with symptoms of necrotizing fasciitis caused by cryptoglandular infection in the perianal and perineal region. The symptoms of necrotizing fasciitis, also known as the cardinal features, include hyperpyrexia, excruciatingly painful lesions, demonstration gas in the tissue, an obnoxious foul odor and uroschesis. The results of postoperative pathology met the diagnosis. Based on the premise of complete debridement, multiple incisions combined with thread-dragging therapy (a traditional Chinese medicine therapy) and intensive supportive therapies including comprising antibiotics, nutrition and fluids were given. The outcome of the treatment was satisfactory. The patient recovered quickly and achieved ideal anal function and morphology.

Timely and effective debridement and multiple incisions combined with thread-dragging therapy are an integrated treatment for necrotizing fasciitis.

Core Tip: Necrotizing fasciitis is a fulminant necrotizing soft tissue disease, which usually progress quickly with a high fatality rate. A basic treatment is timely and thorough debridement. However, an extensive debridement may cause bleeding, nutritional deterioration, or even ends up with dermatoplasty. Here, we report a patient diagnosed with perianal and perineal necrotizing fasciitis. The main treatment is multiple incisions combined with thread-dragging therapy, a common traditional Chinese medicine surgery that usually results in rapid recovery and a low chance of subsequent dermatoplasty. The patient was fully cured and discharged with satisfaction of the treatment.

- Citation: Tao XC, Hu DC, Yin LX, Wang C, Lu JG. Necrotizing fasciitis of cryptoglandular infection treated with multiple incisions and thread-dragging therapy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(28): 8537-8544

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i28/8537.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8537

Perianal necrotizing fasciitis is a rare but life-threatening condition that usually impacts the perianal and perineal regions[1]. The disease progresses rapidly, which can cause systemic sepsis through blood circulation and it is often accompanied by the complications of shock, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and/or death. Meanwhile, most patients with necrotizing fasciitis suffer from various underlying medical conditions. The search of case reports of perianal necrotizing fasciitis in PubMed revealed less than 15 articles in the last 5 years as of March 2021, and most patients in these articles had a variety of underlying diseases including type 2 diabetes and lymphoma. Delay in diagnosis and treatment of this infection may increase the risk of mortality to as high as 76%[2]. The basic treatment principles are early and complete debridement and drainage, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, nutrition supportive therapy, close monitoring of vital signs, and repeated assessments[3]. However, extensive debridement may cause bleeding, nutritional deterioration, and the eventual need of dermatoplasty.

Here, we report a case of a patient who had no underlying diseases but had a medical history of perianal abscess drainage, which was considered to be a case of perianal and perineal necrotizing fasciitis caused by cryptoglandular infection and aggravated by inadequate drainage of perianal abscess. The internal opening was found intraoperatively and the presence of Proteus mirabilis may support the cause. To strike a balance between thorough debridement and less tissue impact, the patient was treated with multiple incisions combined with thread-dragging therapy. The thread-dragging therapy as a standard traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) surgery has the advantages of rapid recovery and less chance for subsequent dermatoplasty.

A 50-year-old male patient was admitted to our institute for perianal swelling and discomfort.

The patient had become aware of anal pain and discomfort with no obvious cause 6 d prior to admission. He did not report abdominal pain, and there was no bleeding during defecation. He had visited the local hospital 2 d earlier for pain, at which time the doctor diagnosed a perianal abscess and performed an incision and drainage. One day later, the perianal swelling had not subsided and had spread to the base of the scrotum; a local incision showed yellowish gray necrotic tissue with a fishy odor. At the same time, the patient developed a high fever. He was admitted to our hospital with a body temperature of 38.2 °C, respiratory rate of 21 breaths/min, heart rate of 81 beats/min, blood pressure of 105/69 mmHg, and dysuresia.

On admission, the case was considered perianal necrotizing fasciitis extending to the perineal region. In contrast to conventional cases of necrotizing fasciitis, the patient denied any underlying diseases. In addition, his physical and laboratory examination confirmed no signs of type 2 diabetes, malignancy, or any of the other common diseases associated with necrotizing fasciitis.

The patient stated that he has no relevant family history.

Physical examination showed that the entire anal margin was swollen and the skin was in red and black. It was also found after palpation that the previous incision on the posterior of the anal margin had yellow-white frothy secretions overflowed. The patient complained of severe pain. The skin on both sides and the base of the scrotum felt tender and warm to the touch, and there was crepitus when palpating the level of the left pubic symphysis (Figure 1).

Laboratory and imaging examinations were promptly performed upon admission. Laboratory examination results during the patient’s hospital stay are shown in Table 1.

| Variable | Reference (range) | On arrival | 2 h postop | The postop day | 3 d postop | 7 d postop | Before discharge |

| White cell count (× 109/L) | 3.50-9.50 | 14.29 | 15.26 | 11.64 | 8.82 | 6.68 | 6.44 |

| Differential count (%) | |||||||

| Neutrophils | 40.00-75.00 | 85.10 | 79.90 | 72.10 | 75.00 | 74.00 | 71.30 |

| Lymphocytes | 20.00-50.00 | 6.70 | 8.30 | 14.30 | 11.00 | 20.00 | 21.70 |

| Monocytes | 3.00-10.00 | 8.00 | 11.60 | 11.30 | 6.00 | 5.00 | 5.90 |

| Eosinophils | 0.40-8.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 2.10 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 130.00-175.00 | 123.00 | 102.00 | 93.00 | 95.00 | 95.00 | 90.00 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 40.00-50.00 | 34.90 | 29.50 | 27.40 | 27.40 | 27.00 | 25.90 |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) | 125.00-350.00 | 135.00 | 132.00 | 174.00 | 256.00 | 314.00 | 281.00 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.00-5.00 | 126.40 | 137.16 | 100.28 | 31.57 | 3.80 | 1.53 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 137.00-145.00 | 140.40 | — | 144.40 | 146.80 | 142.70 | 142.60 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.50-5.50 | 3.50 | — | 3.37 | 3.30 | 3.90 | 3.80 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 98.00-107.00 | 101.20 | — | 110.00 | 108.90 | 104.50 | 105.70 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.10-2.55 | 2.11 | — | 1.80 | 2.10 | 2.17 | 2.10 |

| Urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 3.20-7.10 | 7.08 | — | 6.15 | 5.20 | 3.75 | 3.37 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 58.00-110.00 | 81.30 | — | 73.20 | 46.30 | 42.80 | 43.70 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.10-5.90 | 7.02 | — | 5.50 | — | — | — |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 13.00-69.00 | 35.00 | — | 24.00 | 31.00 | 40.00 | 45.00 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 15.00-46.00 | 35.00 | — | 24.00 | 26.00 | 36.00 | 31.00 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35.00-50.00 | 33.70 | — | 24.50 | 32.20 | 35.90 | 34.40 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | < 0.55 | 7.30 | — | 2.75 | 6.47 | 4.29 | 2.03 |

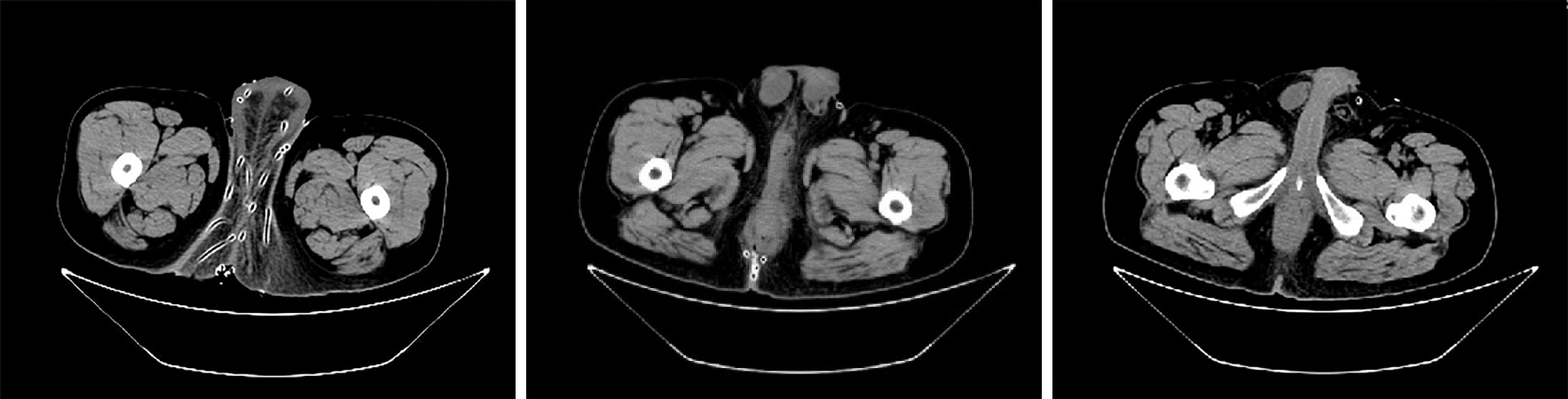

A lower abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan suggested necrotizing fasciitis based on the demonstration of gas in the tissue on both sides of the buttocks, left perineal area, the subcutaneous soft tissues of the groin and the root of the thigh. The scan also showed urine retention and multiple lymph nodes in the inguinal area (Figure 2).

After a comprehensive assessment of symptoms, signs and the examination results, the patient was diagnosed with perianal and perineal necrotizing fasciitis, unfortunately aggravated by inadequate drainage in the early stage.

Based on a clear diagnosis, the operation was performed under timely spinal anesthesia. To distinguish the structure and avoid urethra damage, urethra catheter surgery was performed before surgery. Under a lithotomy position, an obvious defect was found in the anal gland near the posterior dentate line, which was considered to be the primary opening, and the defect was connected to the previous wound. Therefore, it was inferred that the internal opening was the resource of this infection, which means the case was caused by cryptoglandular infection and aggravated by the poor drainage.

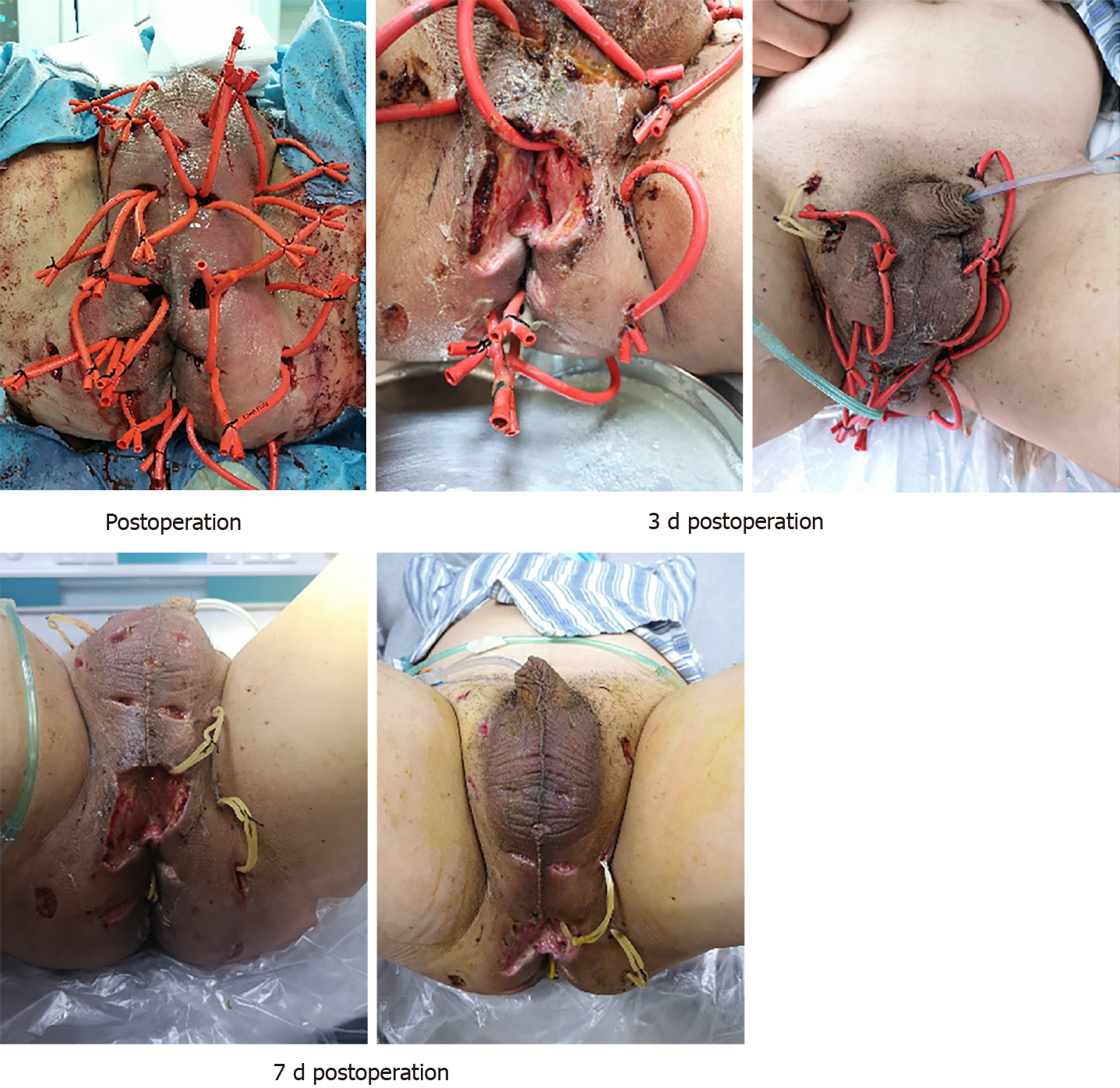

During the surgery, the main incision between the previous wound and the internal opening was completely excised and debrided. A probe and clamp were used to explore the infection area and scissors and diathotomy were used to remove the necrotic tissues. Multiple incisions were performed in the epidermis within a distance of 5 to 8 cm from the main incision. Later, other incisions were performed in the epidermis within a distance of 5 to 8 cm from the former ones until the outermost incision enveloped the entire area of infection. Rubber catheters were used as loose setons for adequate drainage between the incisions on two ends. Finally, the incision outside the level of the bilateral symphysis pubis reached outward of the skin on both sides of the ischium nodules and a total of 21 loose rubber setons were used for these incisions. It is important to keep the skin at the base of the scrotum intact to avoid extensive damage and postoperative sexual dysfunction.

The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit after surgery. Fourth-generation cephalosporin and metronidazole were given to control the infection, and human blood albumin, vitamins, lipids, and other essential nutrition were administered as supportive treatments. Daily laboratory examination was performed to observe the dynamic changes and to adjust treatment (Table 1). The wound was cleaned and changed daily. The surgical area was rinsed with 1:1 hydrogen peroxide and oxygenate and the necrotic tissue was trimmed. The rubber setons were removed after pus was no longer observed.

Three days after surgery, the necrotic perineal skin was completely removed. Another CT scan of lower abdomen and pelvis showed the loose setons around the anus, buttocks, perineum, and scrotum, with a small amount of gas shadow and catheter drainage (Figure 3). A final drainage incision was made at the junction of the patient's right groin and pubic symphysis under local anesthesia (Figure 4).

Perianal magnetic resonance imaging and laboratory examinations (Table 1) were performed 1 wk after the surgery, and all results showed the patient was stable. He was transferred to the general ward in the anorectal department. The antibiotic treatment was stopped but nutrition support continued. Daily dressing changes were performed as described above (Figure 4).

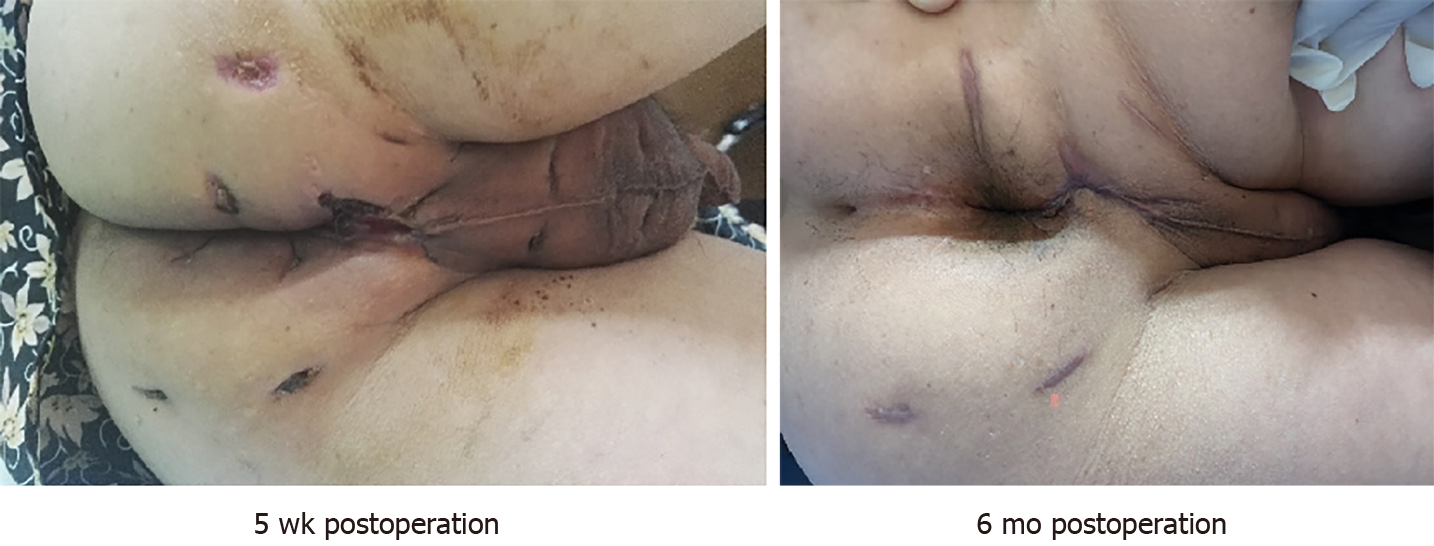

Two weeks after admission, the patient clinically improved and was discharged with the stable laboratory examination results (Figure 5 and Table 1). He continued to visit the outpatient department for examination once a week. Most parts of wound had healed at 3 wk after discharge (Figure 6). At the 6 mo follow-up, the perianal morphology was retained (Figure 6), and anorectal manometry results indicated the function had recovered. The patient was cured and satisfied with the treatment.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a fulminant soft tissue disease with a high fatality rate. The affected patients often have comorbid diabetes, tumors, hypohepatia, chronic renal failure, immune system disorders and other chronic conditions[4]. In this case, the patient denied any underlying disease, but he presented with varying signs and symptoms including fever greater than 38 ℃, scrotal swelling, purulence or wound discharge and flatulence All symptoms and signs led to a tentative diagnosis[5]. A strong “repulsive, fetid odor” is also one overwhelming feature of the presentation that is associated with the condition. Thus, combined with the examination results, the diagnosis can be clearly defined as perianal and perineal necrotizing fasciitis.

The peculiarity of this case is the cause, and the intraoperative examination gave the answer. An obvious defect on the anal gland confirmed the cryptoglandular infection was the resource of the subsequent necrotizing fasciitis. More confirmation of this point was the pus culture. It showed the presence of Proteus mirabilis, which is usually be found in the intestinal and urinary tracts[6], not a common pathogen of necrotizing fasciitis. A review of the present illness history bears out that necrotizing fasciitis onset is largely related to poor drainage of perianal abscesses and failed treatment of the infected internal opening in the early stage. It emphasizes the importance of complete debridement and drainage for perianal abscesses[7]. Early identification and treatment of the infection source are critical when addressing severe perianal infections[8]. In this case, the patient's condition was under control after the internal opening was completely excised and debrided.

What’s more, the key to cure necrotizing fasciitis is timely and thoroughly debriding the affected area[9]. The reason why we performed surgery immediately after the patient’s admission was based on the symptoms and examination findings, which surely confirmed the diagnosis. Since necrotizing fasciitis is always caused by anaerobic bacteria, complete debridement is one of the treatment principles. Drainage of the wounds makes the oxygen in the air to react with anaerobic bacteria. The physiological effects have the ability to enhance leukocyte to kill aerobic bacteria, stimulate the formation of collagen and increase the levels of superoxide dismutase, resulting in better tissue survival[10]. Hydrogen peroxide is also used to achieve this effect in dressing change. Sometimes, patients will even be placed in an environment of increased ambient pressure for breathing 100% oxygen to take hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Adequate oxygenation has the benefits of optimal neutrophil phagocytic function, inhibition of anaerobic growth, increased fibroblast proliferation and angiogenesis, reduction of edema by vasoconstriction, and increased intracellular antibiotics transportation[11]. More and more studies demonstrated that hyperbaric oxygenation is an important therapeutic adjunct in the treatment of necrotizing fasciitis[12], including improving the effectiveness of several antibiotics such as vancomycin and ciprofloxacin.

When it comes to antibiotics, empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be instituted as soon as possible according to the guidelines. Since the pathogens of necrotizing fasciitis also include staphylococcal and streptococcal bacteria, gram-negative, coliforms, pseudomonas, bacteroides, and clostridium, third or fourth generation cefalosporins, aminoglycosides, metronidazole and penicillin are all recommended, which is called a classically triple therapy[2]. Fourth-generation cephalosporin and metronidazole were given in this case. And some clinical guidelines recommend the use of carbapenems or piperaziline-tazobactam to replace the classically triple therapy for the advantages of larger distribution and lesser renal toxicity[13].

In our experience, although debridement is conducive to adequate oxygen, extensive skin damage caused by surgery may generate other side effects, such as increasing the risks of postoperative hypoproteinemia, wound bleeding, slow healing and dermatoplasty. Mallikarjuna suggested debridement should be stopped when separation of the skin and the subcutaneous is not performed easily, because the cutaneous necrosis is not a good marker[14]. Keeping as much normal skin tissue as possible may avoid large scale scar. In particular, a large scar at the base of the scrotum may cause erection difficulties due to scar contracture, which need further scrotal skin flap or dermatoplasty[15]. Even skin grafting was used, the penis and scrotum may still lose normal shape and form artificial deformity. It means the patient may loss the normal erection function, or get barely erection with no normal intercourse[16]. Therefore, we insist that attention should be paid to the protection of scrotal skin at the first time.

In this case, we performed multiple incisions and implanted loose rubber setons to minimize skin and muscle tissue damage on the basement of complete drainage and oxygenation. This approach was combined with standard anti-infective treatment and nutrition support therapy. The patient was discharged 2 wk post-operation and fully recovered 5 wk post-operation. Thorough debridement in this case did not require the removal of all the skin and tissue involved; rather, we ensured that the drainage orifice reached the edge of the lesion, and the central area was addressed with incisions to ensure complete drainage. The use of multiple incisions reduced damage and maintained morphology; it also decreased fluid leakage, reduced energy consumption, thus less nutrition support was required. Satisfactory treatment results were obtained by removing necrotic tissue during daily dressing changes, which means “Staged Therapy,” also called “Canshi Therapy” in TCM, a special method that is just like silkworm eating the mulberry leaf.

We describe a case with necrotizing fasciitis of cryptoglandular infection in the perianal and perineal region that was successfully treated in our hospital. We hypothesize that the timely diagnosis and thorough treatment are the main reasons for the positive outcome. Meanwhile, multiple incisions combined with thread-dragging therapy expressed a curative effect with more effective tissue protection and accelerated recovery comparing to the traditional complete debridement.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: De Nardi P, Liakina V S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | Davis BR, Kasten KR. Anorectal abscess and fistula. In: Steele SR, Hull TL, Read TE, Saclarides TJ, Senagore AJ, Whitlow CN. The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. 3rd ed. Springer, 2016: 223-224. |

| 2. | Benjelloun el B, Souiki T, Yakla N, Ousadden A, Mazaz K, Louchi A, Kanjaa N, Taleb KA. Fournier's gangrene: our experience with 50 patients and analysis of factors affecting mortality. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Clinical Guidelines Committee; Colorectal Surgeons Branch of Chinese Medical Doctor Association. [Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of perianal necrotizing fasciitis (2019)]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2019;22:689-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rebai L, Daghmouri A, Boussaidi I. Necrotizing fasciitis of chest and right abdominal wall caused by acute perforated appendicitis: Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:32-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yeniyol CO, Suelozgen T, Arslan M, Ayder AR. Fournier's gangrene: experience with 25 patients and use of Fournier's gangrene severity index score. Urology. 2004;64:218-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tiri B, Priante G, Mariottini A, Sensi E, Gioia S, Costantini MM, Andreani P, Martella LA, Vernelli C and Cappanera S. Endocarditis of Native Valve due to Proteus mirabilis: Case Report and Literature Review. SN Compr Clin Med. 2021;3:312-316. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vogel JD, Johnson EK, Morris AM, Paquette IM, Saclarides TJ, Feingold DL, Steele SR. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:1117-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sharpe JP, Magnotti LJ, Weinberg JA, Shahan CP, Cullinan DR, Marino KA, Fabian TC, Croce MA. Applicability of an established management algorithm for destructive colon injuries after abbreviated laparotomy: a 17-year experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:636-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Baig MZ, Aziz A, Abdullah UEH, Khalil MS, Abbasi S. Perianal Necrotizing Fasciitis with Retroperitoneal Extension: A Case Report from Pakistan. Cureus. 2019;11:e5052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chennamsetty A, Khourdaji I, Burks F, Killinger KA. Contemporary diagnosis and management of Fournier's gangrene. Ther Adv Urol. 2015;7:203-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Capelli-Schellpfeffer M, Gerber GS. The use of hyperbaric oxygen in urology. J Urol. 1999;162:647-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jallali N, Withey S, Butler PE. Hyperbaric oxygen as adjuvant therapy in the management of necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 2005;189:462-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jimeno J, Díaz De Brito V, Parés D. [Antibiotic treatment in Fournier's gangrene]. Cir Esp 2010; 88: 347-348; author reply 348-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mallikarjuna MN, Vijayakumar A, Patil VS, Shivswamy BS. Fournier's Gangrene: Current Practices. ISRN Surg. 2012;2012:942437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Guo L, Zhang M, Zeng J, Liang P, Zhang P, Huang X. Utilities of scrotal flap for reconstruction of penile skin defects after severe burn injury. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49:1593-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ying J, Yao DH, Cheng KX, Ren XM, Shu MJ, Yao HJ. [Reconstruction of extended skin defect after the radical resection procedure for penile scrotum skin cancer]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2007;45:1257-1259. [PubMed] |