Published online Oct 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8518

Peer-review started: April 6, 2021

First decision: April 28, 2021

Revised: May 12, 2021

Accepted: August 5, 2021

Article in press: August 5, 2021

Published online: October 6, 2021

Processing time: 175 Days and 2.1 Hours

We report a case of intragallbladder hematoma and biliary tract obstruction caused by blunt gallbladder injury. We report that the patient was safely treated by conservative treatment after the obstruction was resolved by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

A 67-year-old man was admitted via the emergency department due to complaints of right-sided abdominal pain that started 2 d prior. Four days prior to presentation, the patient had slipped, fallen and struck his abdomen on a motorcycle handle. His initial vital signs were stable. On physical examination, he showed right upper quadrant pain and Murphy’s sign, with decreased bowel sounds. Additionally, he had had a poor appetite for 4 d. He had been on aspirin for 2 years due to underlying hypertension. Initial simple radiography revealed a slight ileus. The laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cell count, 15.5 × 103/µL (normal range 4.8 × 103–10.8 × 103); hemoglobin, 9.4 g/dL; aspartate aminotransferase/alanine transferase, 423/348 U/L; total bilirubin/direct bilirubin, 4.45/3.26 mg/dL; -GTP , 639 U/L (normal range 5–61 U/L); and C-reactive protein, 12.32 mg/dL (0–0.3). Abdominal computed tomography showed a distended gallbladder with edematous wall change and a 55 mm × 40 mm hematoma. Dilatation was observed in both the intrahepatic and common bile duct areas. Antibiotic treatment was initiated, and ERCP was performed, with hemobilia found during treatment. After cannulation, the patient’s symptoms were relieved, and after conservative management, the patient was discharged with no further complications. After 1-month follow-up, the gallbladder hematoma was completely resolved.

In the case of traumatic injury to the gallbladder, conservative treatment is feasible even in the presence of hematoma.

Core tip: Intragallbladder hematoma is a rare event in trauma. Most of the hematomas in the gallbladder and blunt traumatic injury of the gallbladder itself can lead to complications such as delayed perforation, gallstone formation due to clot retention, and hemorrhagic cholecystitis. In most cases, these gallbladder hematomas require cholecystectomy or external drainage. However, such as in our case, after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed and retention of the tract was resolved, conservative treatment should be considered as a treatment option if the laboratory test results show improvement, and the patient shows a favorable clinical course.

- Citation: Jang H, Park CH, Park Y, Jeong E, Lee N, Kim J, Jo Y. Spontaneous resolution of gallbladder hematoma in blunt traumatic injury: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(28): 8518-8523

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i28/8518.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8518

Intragallbladder hematoma is a rare event in trauma. Most hematomas of the gallbladder, as well as blunt traumatic injury of the gallbladder itself, can lead to complications such as delayed perforation, gallstone formation due to clot retention, and hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Therefore, in most cases, these gallbladder hematomas require cholecystectomy or external drainage. Here, we report a case of intragallbladder hematoma and biliary tract obstruction caused by blunt gallbladder injury. Despite the large hematoma causing formation of gallbladder stones and prominent symptoms, the obstruction was removed, and there was spontaneous resolution of the hematoma. We show that, in the case of traumatic injury to the gallbladder, conservative treatment is feasible even in the presence of hematoma.

A 67-year-old man was admitted via the emergency department due to right-sided abdominal pain that started 2 d prior.

Four days prior to presentation, the patient had slipped and fallen, striking his abdomen on a motorcycle handle. The initial vital signs were stable.

He had been taking aspirin for 2 years due to underlying hypertension.

He had been experiencing a poor appetite for 4 d.

Additionally, on physical examination, the patient showed right upper quadrant pain and Murphy’s sign, with decreased bowel sounds.

The laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cell count, 15.5 × 103/µL (normal range 4.8 × 103–10.8 × 103); hemoglobin, 9.4 g/dL; aspartate aminotransferase/alanine transferase, 423/348 U/L; total bilirubin/direct bilirubin, 4.45/3.26 mg/dL; -GTP 639 U/L (normal range 5–61 U/L); and C-reactive protein, 12.32 mg/dL (normal range 0–0.3 mg/dL).

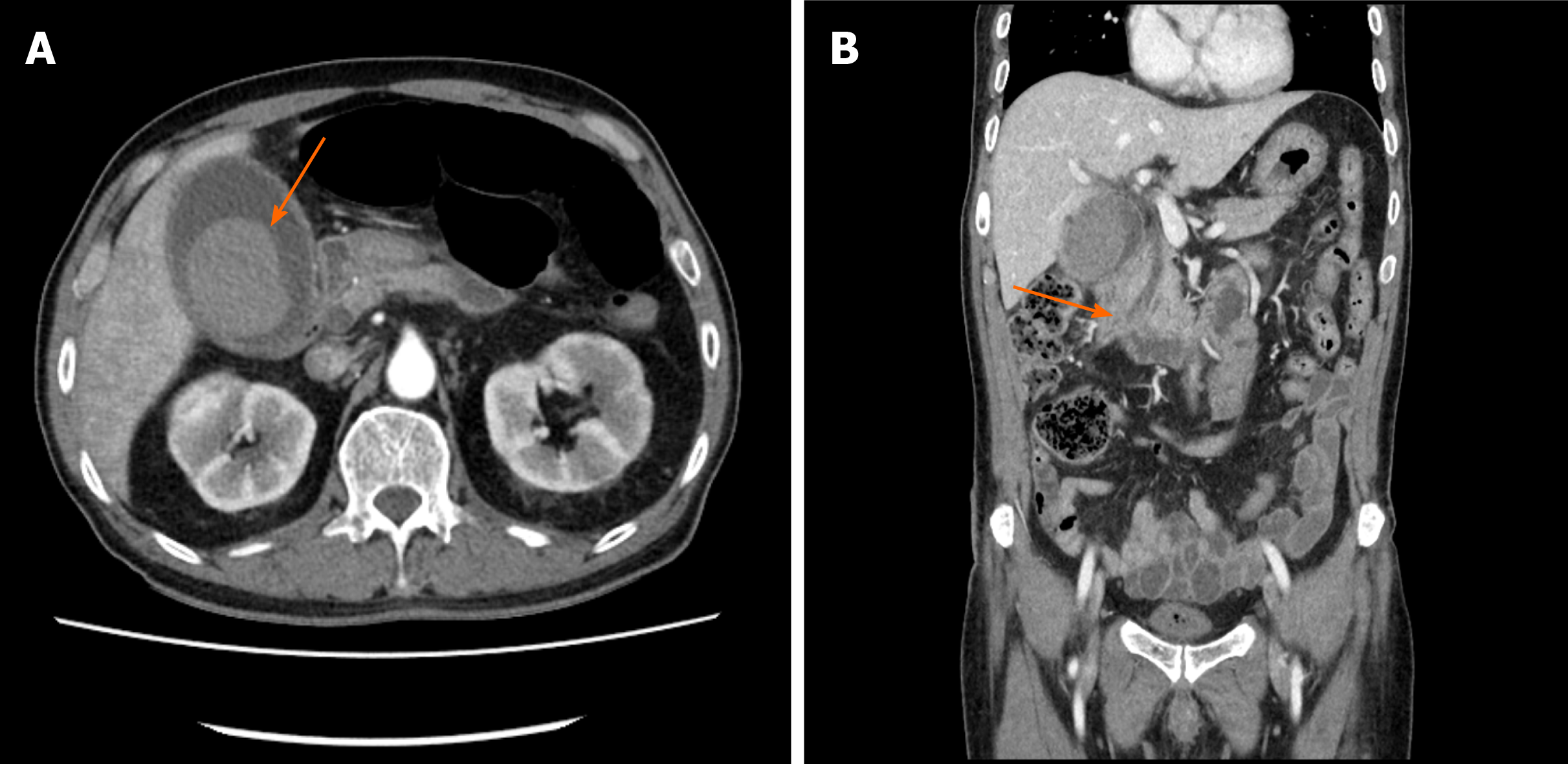

An initial simple radiography revealed a slight ileus (Figure 1). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a distended gallbladder with edematous wall change and a 55 mm × 40 mm hematoma.

The patient had biliary colic pain, and laboratory findings showed elevations in bilirubin and liver function enzymes and a markedly increased γ-glutamyl transferase level. Furthermore, the intrahepatic bile duct dilatation finding on CT suggested a common bile duct obstruction. Based on these findings, gallbladder hematoma (55 mm × 40 mm) with common bile duct obstruction due to traumatic injury was diagnosed.

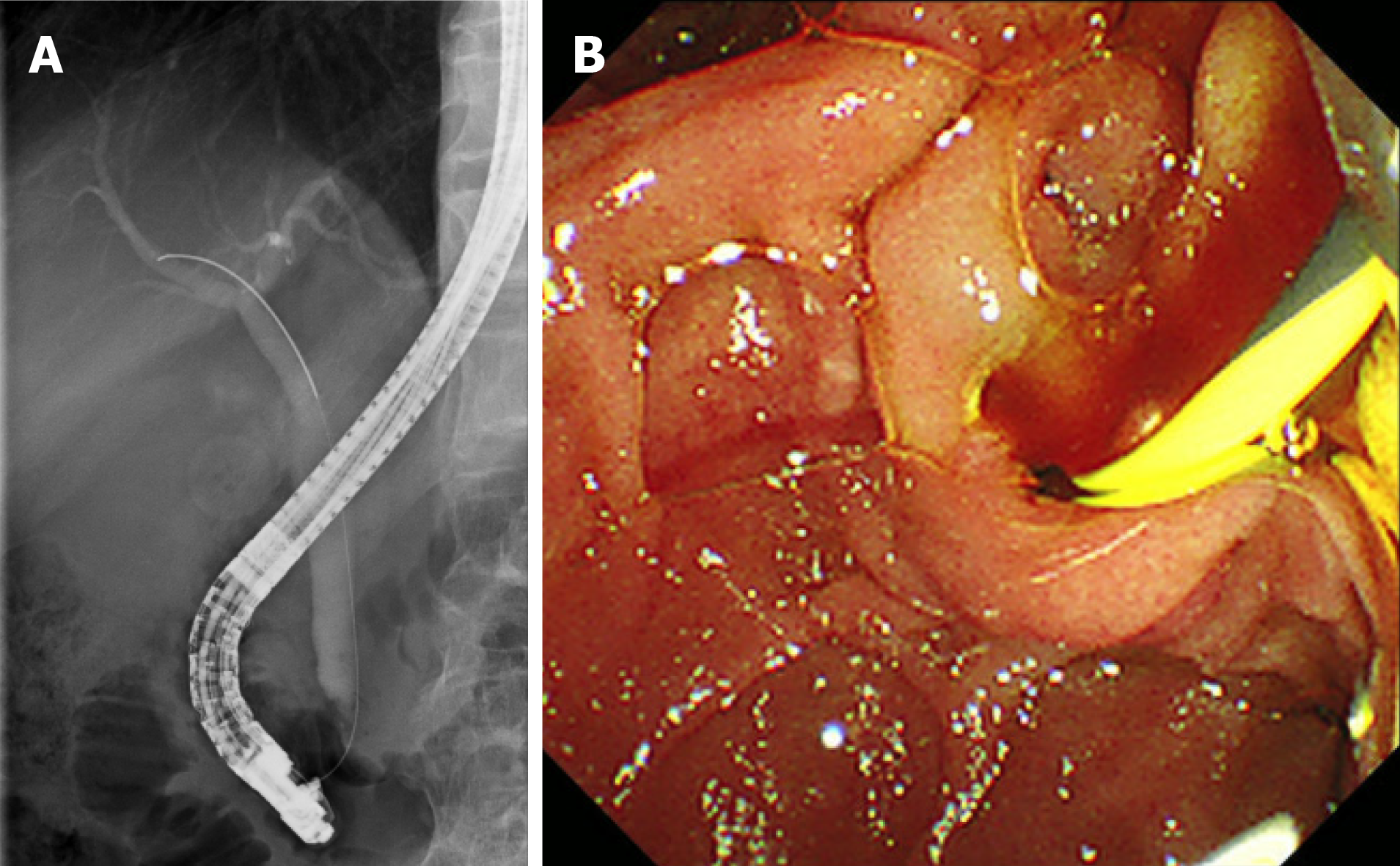

Following antibiotic treatment, we performed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). There was a suspicion of amorphous filling defects in the common bile duct. Hemobilia was observed on cannulation during endoscopy (Figure 2). We deployed a 5 Fr, 4-cm, single-pigtail plastic stent. After stent deployment, the patient’s symptoms were slightly relieved, and the laboratory findings showed improvement. After antibiotic treatment with 2 g cefotaxime and 500 mg metronidazole every 8 h for 5 d, the patient was discharged.

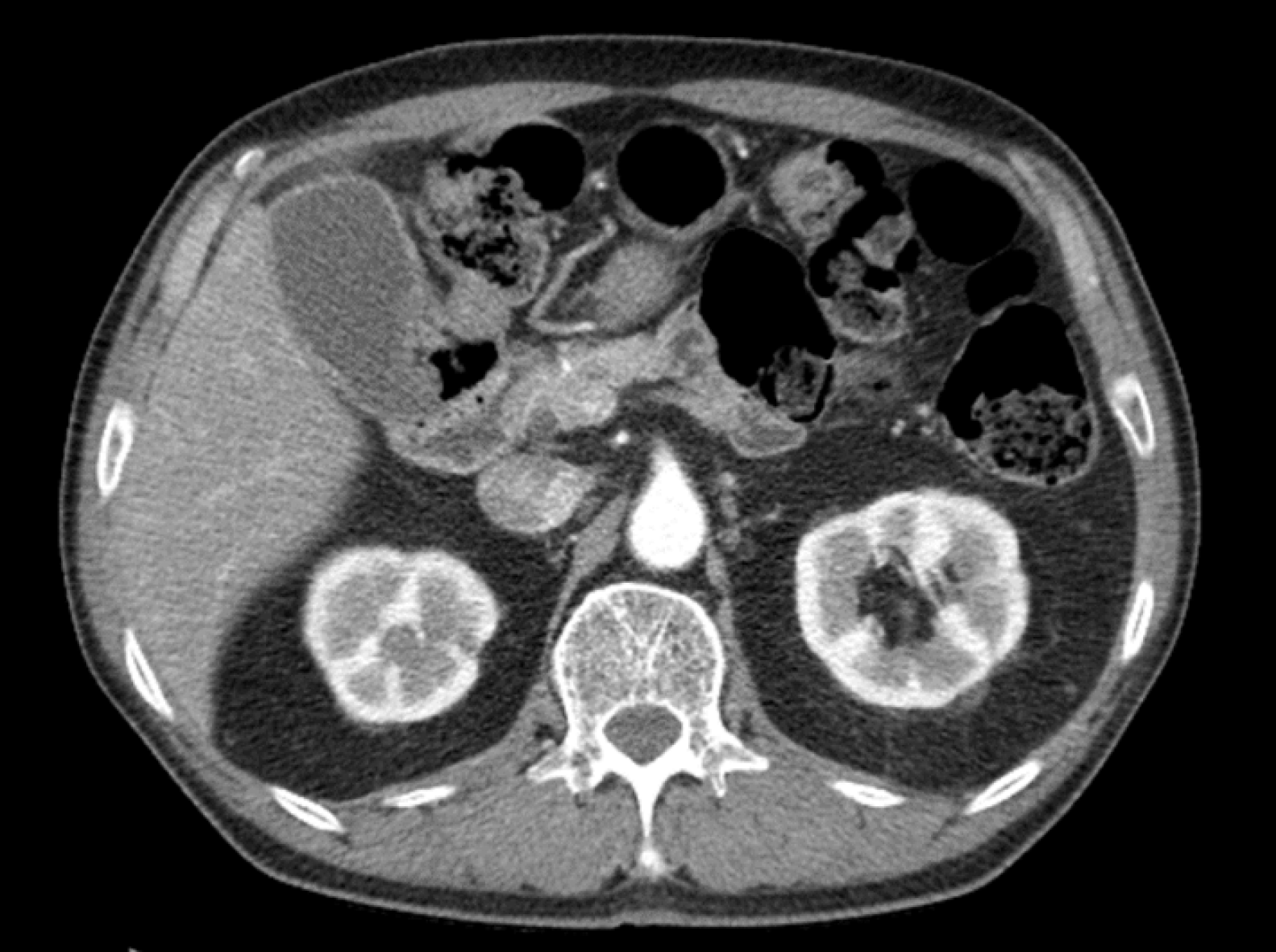

After a 1-week interval, the patient revisited the hospital due to slight abdominal discomfort and constipation, after which he was admitted to the inpatient ward for close observation. On admission, a stool softener was administered, as stool impaction was observed on abdominal X-rays, and the patient had constipation. The abdominal pain was relieved, and no other specific symptoms or fever developed. The laboratory findings were within the normal ranges without antibiotic treatment. In the follow-up CT performed after 10 d, hematoma and distension showed improvement, but mild edematous wall thickening of the gallbladder remained. The stent had been spontaneously removed. The patient’s course was uneventful, and he was discharged 1 wk after CT follow-up. When the patient visited our clinic for the 1-month follow-up, abdominal CT showed an improved hematoma and a distended gallbladder with mild edematous wall thickening (Figure 3).

Intragallbladder hematoma injury accounts for < 2% of blunt intra-abdominal injuries[1,2]. Intra-abdominal hematoma frequently occurs in patients with underlying conditions such as anticoagulation therapy, cirrhosis, renal failure, or even angiosarcoma[3]. Therefore, in traumatic events, checking a patient’s medication history or underlying disease state is crucial[4,5].

Cholecystitis symptoms such as right upper quadrant tenderness, fever, and leukocytosis might occur in blunt injury with intragallbladder hematoma. In addition, symptoms such as hematemesis, melena, and hemobilia may also occur. Most hematomas in the gallbladder lead to blood clots and obstruction of the common bile duct. This can result in cholangitis, which should be closely monitored, as a delay in diagnosing the obstruction can worsen the prognosis[6,7].

Furthermore, blunt traumatic injury of the gallbladder itself can lead to other complications, such as delayed perforation, gallstone formation due to clot retention, and hemorrhagic cholecystitis. In such cases, if there is no improvement, cholecystitis requires surgery. In patients who are unstable, cholecystostomy can be an option[5,8].

Due to concerns of delayed complications such as gallbladder necrosis or ischemia, physicians are reluctant to provide conservative treatment[2,9].

However, as in our case, after retention of the bile tract is resolved, conservative treatment should be considered as an option if the laboratory test results show improvement and the patient shows a favorable clinical course.

Our decision on conservative treatment was challenging. As a surgeon, treatment by a surgical approach is a tempting method and is easily performed. However, considering the patient’s symptoms and laboratory findings, we decided to consider other treatment options. In this patient’s case, after ERCP and cannulation were performed, the patient’s abdominal tenderness improved daily. Furthermore, the patient’s gallstones were spontaneously formed by hematoma, his fever was relieved, and his laboratory findings decreased to within the normal ranges. With symptom improvement and no other complications, stopping antibiotics was the final consideration for treatment that was completed with a conservative approach.

However, before considering conservative treatment, it is necessary to confirm whether there are other accompanying intra-abdominal injuries in the patient and whether the required treatment of such injuries is likely to prolong the hospital stay. Furthermore, in cases where gallbladder stones are present or the clinical manifestation is cholecystitis, surgery or cholecystostomy should be considered as treatment options. This patient’s gallbladder hematoma size gradually decreased and completely resolved after long-term follow-up. Therefore, no other interventions were needed.

The clinical picture of cholelithiasis and cholecystitis usually occurs in acute or chronic forms. Acute cholecystitis usually requires treatment with antibiotics or cholecystectomy. In the case of acute cholecystitis, gallbladder resection is a common treatment of choice after diagnosis. If urgent cholecystectomy is not possible, surgery can be postponed until the acute course of symptoms is resolved. If symptoms resolve and the processes are controlled, surgery can then be selectively performed.

We searched PubMed for a review of treatment options for similar cases of traumatic gallbladder hematoma. In a case reported by Nishiwaki et al[10], the patient was managed conservatively over 30 d and eventually underwent cholecystectomy. In this case, the patient had liver cirrhosis and consistent anemia detected during the admission period. For further evaluation, the authors performed ultrasonography-guided aspiration. In these circumstances, continuing conservative treatment may have resulted in a fatal situation.

When the diagnosis is unclear in isolated gallbladder injury, CT scan and cholecystectomy are considered the treatment of choice, as reported by Birn et al[11]. This was supported by the postoperative diagnostic results in Birn et al[11] case of a partially avulsed gallbladder specimen that was not identified on CT.

In a blunt trauma case reported by Tudyka et al[12], a hydroptic gallbladder with intraluminal hematoma and dilatation of the common bile duct was found in the patient’s CT scan. Without other options, the patient underwent explorative laparotomy, and cholecystectomy was performed. There was no perforation of the resected gallbladder, and a large intraluminal hematoma was seen in the specimen. In a similar case of isolated blunt gallbladder trauma with intraluminal hemorrhage reported by Como et al[13], the patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to suspected hemorrhagic findings in the gallbladder on CT scan. Even though the patient had tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, combined right second to fourth rib fractures and pneumothorax may have also explained their pain. As seen in our case, conservative treatment options may have been carefully considered in these two cases.

ERCP treatment might also cause iatrogenic complications. In a case report by Staszak et al[14], ERCP with stent placement was performed to treat hemobilia of cholangitis, and after the procedure, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed the following day for the treatment of combined cholecystitis. However, after these interventions, pseudoaneurysms of the posterior margins of the liver just above the gallbladder border developed. Even if this case was not caused by traumatic events, the risks of hemobilia and ERCP treatment should not be underestimated.

Our case showed spontaneous resolution even with the presence of a large (4 × 5 cm) gallbladder hematoma. Therefore, when symptoms occur, it is important to determine the cause of biliary colic pain before proceeding with cholecystitis treatment. In fact, in our patient, a stepladder pattern was seen on simple radiography, and physical examination showed increased bowel sounds at the time of the visit. This can be seen as a visceral pain pattern caused by blockage of the cystic duct, and the contractions were caused by the impacted stone. In most cases, the presence of blunt injury cannot rule out that of coexisting bowel injury; therefore, it is important to monitor for this type of pain.

If pain persists and worsens, treatment should be determined based on the development of additional cholecystitis, cholangitis, or accompanying pancreatitis.

In this patient, the stone-like hematoma of the gallbladder spontaneously resolved; however, if it remained in the form of a gallstone after treatment, the course of the disease was monitored periodically. If there is recurrent pain in the form of biliary colic pain that leads to later inflammation, surgical treatment would have been needed.

Despite the relatively large hematoma in the form of gallbladder stones and prominent symptoms, conservative treatment may be an effective treatment option if obstruction of the bile duct is resolved.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu FX S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Wiener I, Watson LC, Wolma FJ. Perforation of the gallbladder due to blunt abdominal trauma. Arch Surg. 1982;117:805-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Soderstrom CA, Maekawa K, DuPriest RW Jr, Cowley RA. Gallbladder injuries resulting from blunt abdominal trauma: an experience and review. Ann Surg. 1981;193:60-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhang X, Zhang C, Huang H, Wang J, Zhang Y, Hu Q. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis with rare imaging presentation: a case report and a lesson learned from neglected medication history of NSAIDs. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | McFadden DW, Smith GW. Hemodialysis-associated hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:1081-1083. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Chen YY, Yi CH, Chen CL, Huang SC, Hsu YH. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis after anticoagulation therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:338-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Goel V, Kumar N, Soni N. Ruptured Gall Bladder containing Stones following Blunt Trauma Abdomen: A Rare Presentation of Hemodynamic Instability. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2015;53:34-36. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lauria AL, Bradley MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Franklin BR. Hemorrhagic Cholecystitis: An Uncommon Disease Resulting in Hemorrhagic Shock. Am Surg. 2019;85:e279-e281. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ma Z, Xu B, Wang L, Mao Y, Zhou B, Song Z, Yang T. Anticoagulants is a risk factor for spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of gallbladder: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2019;19:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sharma O. Blunt gallbladder injuries: presentation of twenty-two cases with review of the literature. J Trauma. 1995;39:576-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nishiwaki M, Ashida H, Nishimura T, Kimura M, Yagyu R, Nishioka A, Utsunomiya J, Yamamura T. Posttraumatic intra-gallbladder hemorrhage in a patient with liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:282-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Birn J, Jung M, Dearing M. Isolated gallbladder injury in a case of blunt abdominal trauma. J Radiol Case Rep. 2012;6:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tudyka V, Toebosch S, Zuidema W. Isolated Gallbladder Injury after Blunt Abdominal Trauma: a Case Report and Review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2007;33:545-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Como JJ, Schieda J, Claridge JA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy after isolated blunt gallbladder trauma resulting in intraluminal hemorrhage: computed tomography and operative findings. Am Surg. 2013;79:E160-E161. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Staszak JK, Buechner D, Helmick RA. Cholecystitis and hemobilia. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;2019:rjz350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |