Published online Oct 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8413

Peer-review started: March 22, 2021

First decision: May 11, 2021

Revised: May 12, 2021

Accepted: August 16, 2021

Article in press: August 16, 2021

Published online: October 6, 2021

Processing time: 190 Days and 1.3 Hours

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common autoimmune disease. Nursing education for family caregivers is considered a workable and effective intervention, but the validity of this intervention in RA has not been reported.

To explore whether family caregiver nursing education (FCNE) works on patients with RA and the factors that influence FCNE.

In this randomized controlled study, a sample of 158 pairs was included in the study with 80 in the intervention group and 78 in the control group. Baseline data of patients and caregivers was collected. The FCNE intervention was admi

Baseline characteristics of the intervention and the control groups had no significant difference. Indicators were significantly reduced in the intervention group compared to the control group. The intervention group showed significant differences in stratification of relationship, education duration and age.

The effect of FCNE on RA is multifaceted, weakening inflammation level, alleviating disease activity and relieving mood disorder. Relationship between caregiver and patient, caregiver’s education level and patient’s age may act as impact factors of FCNE.

Core Tip: Education for family caregivers is considered a workable and effective intervention, but the validity of this intervention in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has not been reported. Therefore, we designed a health education program called family caregiver nursing education, a series of professional training courses for family caregivers that focused on care techniques of RA patients and main points of RA-related knowledge. We chose a total of nine characteristic indicators in terms of inflammation level, disease activity and mood disorder for a 6 mo intervention and follow-up to assess the effect of family caregiver nursing education on RA in multiple ways.

- Citation: Li J, Zhang Y, Kang YJ, Ma N. Effect of family caregiver nursing education on patients with rheumatoid arthritis and its impact factors: A randomized controlled trial. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(28): 8413-8424

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i28/8413.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8413

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammation[1]. A recent survey has been reported that the prevalence of RA in the United States population ranges from 0.5% to 0.8%, with rates as high as 1.7% for specific groups of older adults[2]. In China, RA is one of the top ten chronic diseases, and its prevalence has been recorded at 1.02%[3]. Patients not only suffer from reduced physical function but also frequently experience increased mental stress accompanied by depression and anxiety[4]. As RA patients are more likely to be diagnosed between the ages of 35 and 60[5] and the disease is persistent and difficult to eradicate, long-term care is a necessity. Family nursing can no longer be ignored in the care of patients, and family caregivers have become the mainstay of caregivers[6].

Family nursing is gradually emerging, and support for family caregivers is increasingly valued[7]. Nursing education for family caregivers is considered as a workable and effective intervention that directly improves their disease knowledge, physiological management abilities and psychological support skills to provide better care to patients[8]. Studies have shown this intervention plays an active role in the course of specific diseases including stroke[9], asthma[10] and kidney injury[11]. However, the effectiveness of care education for family caregivers of patients with RA has not been reported. In this study, we designed a health education program called family caregiver nursing education (FCNE), a series of professional training courses for family caregivers that focused on care techniques of RA patients and main points of RA-related knowledge. Indicators of inflammation level, disease activity and mood disorder were also collected and followed up to explore the effect of FCNE on patients with RA and its impact factors.

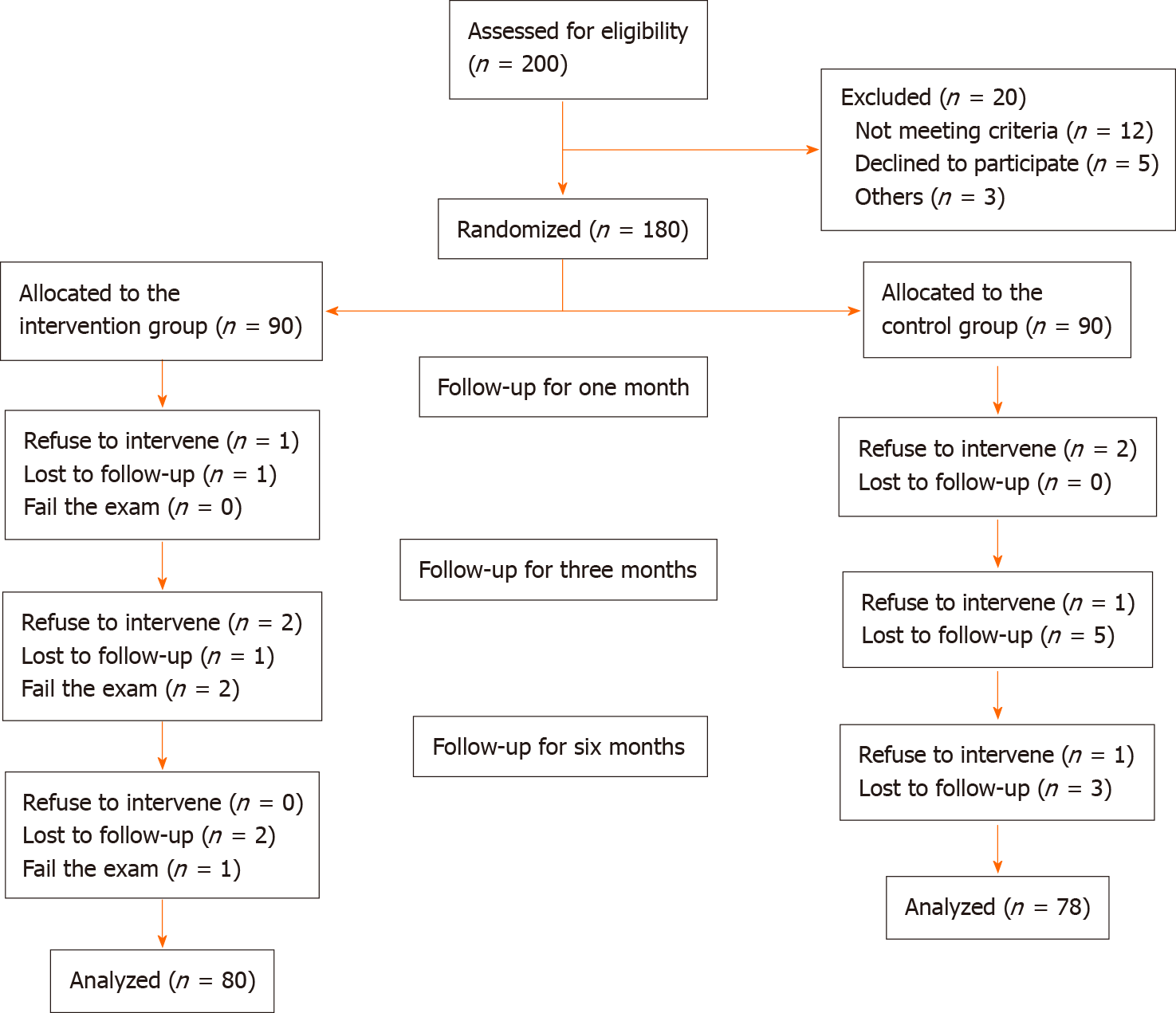

Participants included RA patients and their corresponding family caregivers, and the effect on patients was observed by implementing the intervention on caregivers. Patients were selected from those who were hospitalized in the immune-rheumatology department of a governmental and university-affiliated hospital from June 2017 to December 2018, on the basis of the 2010 revised RA classification criteria of the American Rheumatism Association, the European League Against Rheumatism and the 1987 American College of Rheumatology classification[12]. Each patient was required to have a family carer, on the basis of being the primary caregiver and having lived with the patient for at least 5 years. All patients were not on stable systemic therapy for 1 year, and caregivers have never received training in RA. For this study, the questionnaire had five dimensions for the patient and fifteen for the caregiver for a total of twenty items. According to the Kendall working guidelines, the sample size of the questionnaire was at least five to ten times the number of variables. So we took eight times the number of variables and took into account a 25% margin of error. The sample size was calculated as N = (15 + 5) × 8 × (1 + 25%) = 200. A total of 200 pairs of participants were recruited, among which 158 were included in the final analysis in either the intervention group (n = 80) or the control group (n = 78). Each pair of patients and family caregivers signed an informed consent form, and the study was approved by the hospital ethics committee. The flow diagram for study participants was shown in Figure 1.

By using the computer assignment procedure in SPSS 21.0, sequential numbers were generated and placed in a sealed opaque box, and a separate researcher was arranged to randomly assign the selected participants to the intervention group or the control group. Until all the baseline questionnaires were completed, neither the researchers nor the participants were aware of the group assignment[13].

All patients in both groups received rheumatoid routine primary care and were treated with a uniform regimen of DMARDs represented by methotrexate plus hormonal medication represented by prednisone acetate for 6 mo. In addition, the family caregivers of the intervention group received the FCNE for 6 mo. All interventions were unchanged during the trial.

The original content of FCNE came from literature reviews and consensus guidelines in National Guideline Clearinghouse[14]. A total of eight experienced rheumatologists and nurses then worked together to add, delete, adapt and revise the teaching content in conjunction with expert advice and to develop an appropriate teaching scheme based on the predetermined study period. The final items covered seven primary areas: psychological guidance, medication guidance, functional exercise, diet, clean skin care, care during the active phase of the lesion and care during the stable phase of the lesion. In addition, a brief supplementary course on the epidemiology, pathogenesis and clinical symptoms of RA was interspersed between the main items.

FCNE was carried out around five major approaches: group education, individual training, distribution of written materials, web-based information dissemination and appraisal system. A 45 min one-to-one training and a 1.5 h group training were conducted at regular intervals each month, for a total of six one-to-one training sessions and six group training sessions. Each group training was followed by a workshop on the content of the course and the distribution of the corresponding paper material. Electronic data were released through the network at irregular intervals. A week after each session, participants were followed up by telephone calls of 15 min each, through which researchers checked acceptance and implementation of the last session and arranged additional courses if required[15]. Every 2 wk after the training was completed, an examination was used to test and evaluate the effectiveness of the teaching. For subjects who failed the test, retraining and make-up examinations were conducted. Those who still failed the make-up examination were removed from the intervention group. Those with an attendance rate of less than 80% were also removed from the intervention group. All of the above assessments were randomly assigned to five independent researchers and completed using a double-blind method.

General information of patients and caregivers was collected from questionnaire or medical chart at baseline. Indicators of patients including C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), tender joint counts out of 28 joints (TJC28), swollen joint counts out of 28 joints (SJC28), pain on visual analogue scale, provider global assessment by visual analogue scale (PGA), patient global assessment of disease activity by visual analogue scale (PtGA), health assessment questionnaire (HAQ), self-rating depression scale (SDS) and self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) were followed up at baseline, 1st month, 3rd month and 6th month when patients came for their routine visits. ∆CRP, ∆ESR, ∆TNF-α, clinical disease activity index (CDAI), simplified disease activity index (SDAI) and disease activity score with 28-joint count (DAS28) were respectively calculated by the following formulas: ∆CRP = (baseline CRP - 6th mo CRP)/baseline CRP; ∆ESR = (baseline ESR - 6th mo ESR)/baseline ESR; ∆TNF-α = (baseline TNF-α - 6th mo TNF-α)/baseline TNF-α; CDAI = TJC28 + SJC28 + PGA + PtGA; SDAI = TJC28 + SJC28 + PGA + PtGA + CRP; DAS28 = 0.56√TJC28 + 0.28√SJC28 + 0.70LnESR + 0.014PtGA.

General information: General information included the patient’s age, gender, presence of comorbidity (hypertension, coronary heart disease and diabetes), drug therapy and disease duration and the caregiver’s age, gender, work status, relationship with the patient and education duration (representing the education level).

Indicators of inflammation level: CRP, ESR and TNF-α were used to assess the biochemical level of inflammation; ∆CRP, ∆ESR and ∆TNF-α were used to assess the degree of decline in inflammatory indicators. CRP, ESR and TNF-α are considered to be the main pathophysiological factors in RA. Biomarkers in the blood become higher when inflammation is severe, while ∆CRP, ∆ESR and ∆TNF-α rise accordingly when inflammation subsides[16].

Indicators of disease activity: CDAI, SDAI, DAS28 and HAQ were used to evaluate the level of disease activity in RA. The specific formulas for CDAI, SDAI and DAS28 have been listed previously with TJC28, SJC28, PGA, PtGA, CRP and ESR. HAQ covers daily activities such as dressing, standing, eating, walking and hygiene. High values of these scores indicate deterioration in physical function[15].

Indicators of mood disorder: SDS and SAS were used to appraise the level of mental health and mood disorder. The SDS and SAS assess 20 symptoms of depression and anxiety, respectively, rated numerically on a scale for each item, with higher scores indicating a higher intensity of the symptom in question. SDS ≥ 50 is defined as depression, 50-59 as mild depression, 60-69 as moderate depression and 70 or more as severe depression. SAS ≥ 50 is defined as anxiety, 50-59 as mild anxiety, 60-69 as moderate anxiety and 70 or more as severe anxiety[17]. SDS and SAS have been used to test the psychological level of RA patients[18].

This study utilized SPSS 21.0 software to process the data. A total of 158 cases were ultimately included in the statistical analysis, including 80 cases in the intervention group and 78 cases in the control group. If the quantitative data were normally distributed, the mean ± SD were used to describe. If the data showed a skewed distribution, the median and interquartile range were applied. Frequency and percentage reports were used to describe the categorical data. Depen

In total, 80 pairs were included in the statistical analysis in the intervention group and 78 pairs in the control group. For family caregivers, the majority were women with full-time jobs. The mean age was 47.4-years-old, ranging from 28-years-old to 65-years-old. The median education duration was 9 years, which meant they had senior high school education or near university education. For patients, most were also female, and the mean age was 59.2-years-old distributed between 34-years-old and 86-years-old. Patients with the median disease duration of 5.5 years were mainly treated with DMARDs + glucocorticoid and had no comorbidity. In addition, indicators were counted to assess the patient’s initial condition. There was no significant difference in all general information and indicators between the intervention group and the control group at baseline. Specific values and statistical results of the characteristics were shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Total, n = 158 | IG, n = 80 | CG, n = 78 | t | z | x2 | P value |

| Caregiver characteristics | |||||||

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 47.4 ± 8.4 | 47.7 ± 8.6 | 47.0 ± 8.3 | 0.520 | 0.604 | ||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.933 | 0.334 | |||||

| Male | 44 (27.8) | 25 (31.3) | 19 (24.4) | ||||

| Female | 114 (72.2) | 55 (68.8) | 59 (75.6) | ||||

| Work status, n (%) | 0.141 | 0.932 | |||||

| Full-time | 102 (64.6) | 51 (63.8) | 51 (65.4) | ||||

| Part-time | 24 (15.2) | 13 (16.3) | 11 (14.1) | ||||

| Unemployed | 32 (20.3) | 16 (20.0) | 16 (20.5) | ||||

| Relationship, n (%) | 0.238 | 0.888 | |||||

| Son or daughter | 45 (28.5) | 23 (28.8) | 22 (28.2) | ||||

| Spouse | 62 (39.2) | 30 (37.5) | 32 (41.0) | ||||

| Others | 51 (32.3) | 27 (33.8) | 24 (30.8) | ||||

| Education duration (yr), mean (IQR) | 9.0 (6.0) | 9.0 (6.0) | 9.0 (6.5) | -0.251 | 0.802 | ||

| Patient characteristics | |||||||

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 59.2 ± 10.9 | 60.6 ± 10.7 | 57.7 ± 10.9 | 1.669 | 0.097 | ||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.082 | 0.774 | |||||

| Male | 25 (15.8) | 12 (15.0) | 13 (16.7) | ||||

| Female | 133 (84.2) | 68 (85.0) | 65 (83.3) | ||||

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 0.118 | 0.732 | |||||

| Yes | 28 (17.7) | 15 (18.8) | 13 (16.7) | ||||

| No | 130 (82.3) | 65 (81.3) | 65 (83.3) | ||||

| Drug therapy, n (%) | 0.076 | 0.783 | |||||

| DMARDs + GC | 117 (74.1) | 60 (75.0) | 57 (73.1) | ||||

| DMARDs + GC + biologics | 41 (26.0) | 20 (25.0) | 21 (26.9) | ||||

| Disease duration (yr), mean (IQR) | 5.5 (6.0) | 5.0 (5.0) | 6.5 (4.3) | -1.816 | 0.069 | ||

| CRP (mg/L), mean ± SD | 18.00 ± 5.52 | 17.74 ± 5.65 | 18.25 ± 5.41 | -0.579 | 0.563 | ||

| ESR (mm/h), mean ± SD | 35.49 ± 5.33 | 35.61 ± 5.29 | 35.36 ± 5.41 | 0.298 | 0.766 | ||

| TNF-α (pg /ml), mean ± SD | 43.47 ± 9.58 | 43.93 ± 9.04 | 42.99 ± 10.15 | 0.618 | 0.537 | ||

| CDAI, mean ± SD | 20.00 ± 7.63 | 19.97 ± 7.29 | 20.04 ± 8.01 | -0.060 | 0.952 | ||

| SDAI, mean ± SD | 38.00 ± 8.70 | 37.71 ± 8.67 | 38.29 ± 8.78 | -0.420 | 0.675 | ||

| DAS28, mean ± SD | 4.92 ± 1.30 | 4.94 ± 1.29 | 4.89 ± 1.33 | 0.251 | 0.802 | ||

| HAQ, mean (IQR) | 1.12 (0.99) | 1.21 (0.99) | 1.11 (0.99) | -0.442 | 0.659 | ||

| SDS, mean ± SD | 57.87 ± 5.51 | 57.31 ± 4.77 | 58.45 ± 6.15 | -1.300 | 0.196 | ||

| SAS, mean ± SD | 53.82 ± 9.68 | 54.43 ± 8.34 | 53.21 ± 10.91 | 0.791 | 0.430 | ||

FCNE reduced indicators of inflammation level: All follow-up indicators of the intervention group and the control group were shown in Table 2. Repeated measures ANOVA was performed. Main effect of time and interaction effect of time × group were significant in all inflammation indicators (P < 0.001), meaning that they had a downward trend over time while time interacted with FCNE. Effect of group was also significant in CRP, ESR and TNF-α (P < 0.001, P = 0.001, P = 0.019, respectively), implying that FCNE promoted containment of inflammation and reduced indicators of inflammation level in RA.

| Indicators | IG, n = 80 | CG, n = 78 | ||||||

| Baseline | 1st mo | 3rd mo | 6th mo | Baseline | 1st mo | 3rd mo | 6th mo | |

| Inflammation level | ||||||||

| CRP (mg/L) | 17.74 ± 5.65 | 15.05 ± 4.51 | 10.83 ± 3.84 | 2.40 ± 2.00 | 18.25 ± 5.41 | 16.71 ± 4.42 | 15.13 ± 3.35 | 7.93 ± 2.77 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 35.61 ± 5.29 | 31.57 ± 4.81 | 28.03 ± 3.42 | 23.97 ± 3.14 | 35.36 ± 5.41 | 32.85 ± 4.58 | 29.81 ± 3.36 | 28.21 ± 2.82 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 43.93 ± 9.04 | 38.22 ± 8.05 | 33.24 ± 7.98 | 29.61 ± 6.72 | 42.99 ± 10.15 | 41.01 ± 9.72 | 38.12 ± 9.14 | 35.56 ± 8.12 |

| Disease activity | ||||||||

| CDAI | 19.97 ± 7.29 | 20.00 ± 7.25 | 13.90 ± 5.17 | 4.51 ± 1.94 | 20.04 ± 8.01 | 19.51 ± 7.95 | 17.94 ± 6.93 | 15.41 ± 5.26 |

| SDAI | 37.71 ± 8.67 | 35.06 ± 8.11 | 24.73 ± 5.99 | 6.91 ± 2.49 | 38.29 ± 8.78 | 36.22 ± 8.22 | 33.06 ± 7.03 | 23.34 ± 5.24 |

| DAS28 | 4.94 ± 1.29 | 4.56 ± 1.00 | 4.02 ± 0.78 | 3.40 ± 1.00 | 4.89 ± 1.33 | 4.94 ± 1.29 | 4.50 ± 1.25 | 4.13 ± 0.93 |

| HAQ | 1.39 ± 0.64 | 1.04 ± 0.59 | 1.12 ± 0.65 | 0.36 ± 0.28 | 1.43 ± 0.70 | 1.24 ± 0.72 | 1.22 ± 0.66 | 0.91 ± 0.58 |

| Mood disorder | ||||||||

| SDS | 57.31 ± 4.77 | 46.60 ± 5.67 | 37.63 ± 5.14 | 31.81 ± 9.82 | 58.45 ± 6.15 | 50.95 ± 6.09 | 51.62 ± 5.77 | 49.58 ± 6.13 |

| SAS | 54.43 ± 8.34 | 49.81 ± 7.52 | 40.60 ± 6.32 | 31.71 ± 8.84 | 53.21 ± 10.91 | 53.01 ± 10.84 | 49.22 ± 7.34 | 45.13 ± 9.39 |

FCNE reduced indicators of disease activity: Except that the repeated measures ANOVA result of HAQ did not show significant difference, effect of time and time × group was significant in CDAI, SDAI and DAS28 (P < 0.001), and effect of group was significant in CDAI, SDAI and DAS28 (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P = 0.013, respectively), indicating that FCNE helped to curb disease progression and reduced indicators of disease activity in RA.

FCNE reduced indicators of mood disorder: According to the scoring criteria, at baseline, 77 people were depressed in the intervention group (56 mildly depressed and 21 moderately depressed) and 71 in the control group (41 mildly depressed, 26 moderately depressed and 4 severely depressed), with no significant difference; after 6 mo of follow-up, 10 people were depressed in the intervention group significantly lower than 39 in the control group (P < 0.001). Similarly, 54 people in the intervention group suffered from anxiety at baseline (32 with mild anxiety, 19 with moderate anxiety and 3 with severe anxiety) and 48 in the control group (26 with mild anxiety, 14 with moderate anxiety and 8 with severe anxiety), with no significant difference; after 6 mo of follow-up, 6 people in the intervention group suffered from anxiety significantly lower than 23 in the control group (P < 0.001). In addition, the repeated measures ANOVA result also showed that time, time × group and group effect of SDS and SAS was significant (P < 0.001). All these suggested that FCNE contributed to mental health and reduced indicators of mood disorder in RA.

Relationship between caregiver and patient: The intervention group was reclassified based on the relationship between caregiver and patient: 23 cases in son or daughter group, 30 cases in spouse group and 27 cases in other relationships group. Inflammation indicators of these three groups were shown in Table 3. For CRP, effect of relationship-group was significant (P = 0.033), and further pairwise comparisons revealed that spouse group had a significantly lower reduction in CRP than other relationships group (P = 0.012). For ESR, relationship-group effect was also significant (P = 0.041), and pairwise comparisons showed that ESR reduction of spouse group was significantly lower than that of other relationships group (P = 0.024), while son or daughter group had a significantly lower ESR reduction than other relationships group (P = 0.035). However, TNF-α did not show significant stratification. Both CRP and ESR results suggested a more efficient effect of FCNE for spousal relationship, resulting in a more pronounced reduction in inflammatory indicators. Relationship between caregiver and patient was an impact factor of FCNE.

| Indicators | Son or daughter, n = 23 | Spouse, n = 30 | Others, n = 27 | |||||||||

| Baseline | 1st mo | 3rd mo | 6th mo | Baseline | 1st mo | 3rd mo | 6th mo | Baseline | 1st mo | 3rd mo | 6th mo | |

| CRP (mg/L) | 18.90 ± 5.03 | 15.09 ± 4.43 | 9.45 ± 4.24 | 0.98 ± 0.85 | 20.07 ± 5.45 | 16.27 ± 4.83 | 12.02 ± 3.59 | 2.44 ± 1.93 | 14.18 ± 4.67 | 13.67 ± 3.92 | 10.67 ± 3.43 | 3.55 ± 2.07 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 36.33 ± 3.88 | 32.46 ± 4.77 | 28.28 ± 4.30 | 24.45 ± 3.92 | 38.11 ± 4.23 | 33.13 ± 3.97 | 27.76 ± 2.79 | 22.57 ± 2.34 | 32.24 ± 5.73 | 29.08 ± 4.85 | 28.10 ± 3.33 | 25.12 ± 2.66 |

| TNF-α (pg /mL) | 47.25 ± 9.24 | 40.65 ± 9.04 | 33.57 ± 9.39 | 29.91 ± 7.74 | 44.71 ± 7.49 | 37.84. ± 6.44 | 32.24 ± 6.15 | 28.84 ± 4.62 | 40.24 ± 9.42 | 36.56 ± 8.57 | 34.08 ± 8.65 | 30.22 ± 7.84 |

Education duration of caregiver: The means of ∆CRP, ∆ESR and ∆TNF-α were 84.74% (SD = 14.32%), 31.01% (SD = 14.89%) and 32.03% (SD = 9.75%), respectively. The results of Pearson correlation analysis showed that ∆CRP (r = 0.516, P < 0.001), ∆ESR (r = 0.507, P < 0.001) and ∆TNF-α (r = 0.734, P < 0.001) were significantly and positively correlated with education duration. The longer the caregiver’s education duration, the higher the patient’s inflammation decline, and the better the effect of FCNE, which meant that caregiver’s education duration was an impact factor of FCNE.

Age of patient: The intervention group was reclassified by patient age: 42 cases in middle-aged group and 38 cases in elderly group (the World Health Organization defines 45 years to 59 years as middle-aged people and 60 years and above as elderly people). Disease activity and mood disorder indicators of these two groups were shown in Table 4. For disease activity indicators, except for no difference in HAQ stratification, effect of age-group in CDAI, SDAI and DAS28 was significant (P < 0.001). CDAI, SDAI and DAS28 were higher in the elderly group than in the middle-aged group at baseline, but the level of the elderly group was approaching that of the middle-aged group by the 6th month of follow-up. The degree of disease activity decline was more evident in the elderly group.

| Indicators | Middle-aged people, n = 42 | Elderly people, n = 38 | ||||||

| Baseline | 1st mo | 3rd mo | 6th mo | Baseline | 1st mo | 3rd mo | 6th mo | |

| CDAI | 14.48 ± 4.04 | 14.53 ± 4.02 | 10.07 ± 2.32 | 4.79 ± 1.85 | 26.03 ± 4.84 | 26.05 ± 4.76 | 18.13 ± 1.02 | 4.21 ± 2.00 |

| SDAI | 32.88 ± 6.19 | 30.14 ± 5.57 | 21.65 ± 4.00 | 7.44 ± 2.11 | 43.04 ± 7.89 | 40.49 ± 6.94 | 28.13 ± 6.03 | 6.32 ± 2.76 |

| DAS28 | 4.09 ± 0.75 | 3.85 ± 0.72 | 3.64 ± 0.79 | 3.49 ± 1.03 | 5.88 ± 1.08 | 5.34 ± 0.58 | 4.44 ± 0.52 | 3.30 ± 0.96 |

| HAQ | 1.34 ± 0.63 | 1.12 ± 0.60 | 1.24 ± 0.66 | 0.33 ± 0.20 | 1.45 ± 0.65 | 0.95 ± 0.58 | 0.99 ± 0.62 | 0.39 ± 0.29 |

| SDS | 60.90 ± 3.31 | 48.00 ± 6.54 | 38.50 ± 5.57 | 30.45 ± 8.91 | 53.34 ± 2.35 | 45.05 ± 4.07 | 36.66 ± 4.49 | 33.32 ± 10.66 |

| SAS | 60.90 ± 4.81 | 55.38 ± 5.12 | 45.55 ± 3.60 | 29.71 ± 6.90 | 47.26 ± 4.73 | 43.66 ± 4.21 | 35.13 ± 3.52 | 33.92 ± 10.22 |

For mood disorder indicators, age-group effect for both SDS (P = 0.014) and SAS (P < 0.001) was significant, meaning that the middle-aged group with higher mood disorder scores before the intervention was close to or even lower than the elderly group after 6 mo of FCNE intervention. FCNE had a significant psychological improvement effect on the middle-aged group and a significant disease mitigation effect on the elderly group, showing that patient’s age was another impact factor of FCNE.

Traditional nursing education for RA is aimed at patients. In addition to the patients themselves, to a certain extent, the quality of life for patients also depends on the support of their families[19]. A study has proven that the mood of caregivers also affected the disease progression of RA patients[20]. More studies on family interventions have been published in recent years, and the majority of these showed benefit to the identified patient[21]. But there is little research on nursing education or family nursing for RA patients. Therefore, we designed the FCNE. For the selection of outcome measures, we chose a total of nine characteristic indicators in terms of inflammation level, disease activity and mood disorder for a 6 mo intervention and follow-up. The aim was to assess the effect of FCNE on RA and its influencing factors in a holistic manner.

Initially, we selected biochemical indicators of inflammation for evaluation due to their importance in the pathogenesis of RA[22]. In addition to the two traditional indicators of CRP and ESR[23], we also included TNF-α, an emerging marker of RA[16]. The results found that the intervention group showed a significantly better reduction in all three indicators than the control group, which corroborated the reliability of TNF-α. Afterwards, we calculated and appraised the disease indexes for RA and found that FCNE had a distinct advantage for the reduction of CDAI, SDAI and DAS28 but did not show the same effect for HAQ, probably due to errors caused by small values with insignificant changes. More and more care models were proven to work for RA, and a nurse-led study found that nursing education by telephone was effective in improving medication adherence in RA patients[14]. As a rising approach, FCNE plays a positive role in the prognosis of diseases including lung cancer[24] and stroke[25]. FCNE enhances caregivers’ knowledge of the disease and improves nursing skills, which is conducive to providing better care to patients while identifying risk factors and complications in time to reduce injuries. It also provides a communication platform, bringing participants together for exchange and discussion, which not only allows them to obtain more practical experience but also benefits the release of negative emotions[25].

According to surveys, the prevalence of depression in RA patients is between 14.8% and 48.0%, which is twice that of the general population[26] and increases the mortality rate of RA patients to a certain extent[27]. Relevant studies have shown that FCNE can reduce depression, anxiety and self-harm in certain patient populations, such as ischemic stroke patients[28], older patients[29] and suicidal patients[30]. In this study, the effect of FCNE on alleviating mood disorder and promoting mental health in RA patients was similarly confirmed. This role of FCNE may be achieved by facilitating family communication, relieving misunderstandings and conflicts and supporting the maintenance of an enabling environment characterized by understanding and cooperation[31,32]. The effectiveness of mindfulness interventions for RA[33] also supported this speculation.

After confirming the effect of FCNE on RA, we had a stratified study of the intervention group according to different factors to explore the possible influencing fac

In this study we were surprised to find that FCNE had a significant improvement in a number of indicators, particularly inflammatory indicators including TNF-α, which we hypothesize is related to FCNE improving adherence to drug treatment. Patients with positive adherence to medication may be better able to contain the disease and slow its progression[36]. Several previous studies have confirmed the effectiveness of educational interventions tailored to RA, which are achieved by improving and main

This study has some limitations. Primarily, the sample was small, and it was a single center study. The conclusions have yet to be validated in a large sample and multicenter experiment. Furthermore, there was a slight improvement in some indicators in the control group, which we speculate may be related to the conventional treatment they received and remains to be demonstrated. Finally, based on follow-up data for all indicators, the effect of FCNE is most pronounced after 1 mo and especially between 3 and 6 mo, demonstrating its short-term impact. However, the lack of long-term follow-up has demonstrated its role in relation to the chronic effects.

The effect of FCNE on RA is multifaceted, weakening inflammation level, alleviating disease activity and relieving mood disorder. Relationship between caregiver and patient, caregiver’s education level and patient’s age may act as impact factors of FCNE.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common disease that requires long-term care, and nursing education for family caregivers is considered as a workable and effective intervention.

The effectiveness of care education for family caregivers of patients with RA has not been reported.

This study aimed to explore whether family caregiver nursing education (FCNE) works on patients with RA and the factors that influence FCNE.

In this study, we designed a health education program called FCNE, a series of professional training courses for family caregivers that focused on care techniques of RA patients and main points of RA-related knowledge. The FCNE intervention was administered to caregivers, and inflammation level indicators, disease activity indicators and mood disorder indicators of patients were followed up and analyzed.

Indicators were significantly reduced in the intervention group compared to the control group. The intervention group showed significant differences in stratification of relationship, education duration and age.

The effect of FCNE on RA is multifaceted, weakening inflammation level, alleviating disease activity and relieving mood disorder. Relationship between caregiver and patient, caregiver’s education level and patient’s age may act as impact factors of FCNE.

This study indicates that FCNE is feasible and efficient for patients with RA. It also suggests priorities for FCNE participants, such as giving preference to spouses or caregivers with high education level as they are likely to have better intervention outcomes.

The authors would like to thank all participants for their contribution to the study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Rheumatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dauyey K, Kang JH, Kapritsou M S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wu RR

| 1. | Giannini D, Antonucci M, Petrelli F, Bilia S, Alunno A, Puxeddu I. One year in review 2020: pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38:387-397. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lo J, Chan L, Flynn S. A Systematic Review of the Incidence, Prevalence, Costs, and Activity and Work Limitations of Amputation, Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Back Pain, Multiple Sclerosis, Spinal Cord Injury, Stroke, and Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: A 2019 Update. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:115-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hu H, Luan L, Yang K, Li SC. Burden of rheumatoid arthritis from a societal perspective: A prevalence-based study on cost of this illness for patients in China. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:1572-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Prothero L, Barley E, Galloway J, Georgopoulou S, Sturt J. The evidence base for psychological interventions for rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review of reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;82:20-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bullock J, Rizvi SAA, Saleh AM, Ahmed SS, Do DP, Ansari RA, Ahmed J. Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Brief Overview of the Treatment. Med Princ Pract. 2018;27:501-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Luttik ML. Family Nursing: The family as the unit of research and care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;19:660-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chi NC, Barani E, Fu YK, Nakad L, Gilbertson-White S, Herr K, Saeidzadeh S. Interventions to Support Family Caregivers in Pain Management: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:630-656.e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Monfort E, Mayol A, Lissot C, Couturier P. Evaluation of a therapeutic education program for French family caregivers of elderly people suffering from major neurocognitive disorders: Preliminary study. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018;39:495-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Evans RL, Held S. Evaluation of family stroke education. Int J Rehabil Res. 1984;7:47-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Frey SM, Fagnano M, Halterman JS. Caregiver education to promote appropriate use of preventive asthma medications: what is happening in primary care? J Asthma. 2016;53:213-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mollaoğlu M, Kayataş M, Yürügen B. Effects on caregiver burden of education related to home care in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2013;17:413-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van der Linden MP, Knevel R, Huizinga TW, van der Helm-van Mil AH. Classification of rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria and the 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:37-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shao JH, Yu KH, Chen SH. Effectiveness of a self-management program for joint protection and physical activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;103752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Song Y, Reifsnider E, Zhao S, Xie X, Chen H. A randomized controlled trial of the Effects of a telehealth educational intervention on medication adherence and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76:1172-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhao S, Chen H. Effectiveness of health education by telephone follow-up on self-efficacy among discharged patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomised control trial. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:3840-3847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kaya FÖ, Ceylaner Y, İpek BÖ, Özünal ZG, Sezgin G, Nalbant S. Can Cytokines be used as an Activation Marker in Rheumatoid Arthritis? Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zung WW. The Depression Status Inventory: an adjunct to the Self-Rating Depression Scale. J Clin Psychol. 1972;28:539-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zartaloudi A, Koutelekos I, Polikandrioti M, Stefanidou S, Koukoularis D, Kyritsi E. Anxiety and depression in primary care patients suffering of rheumatoid diseases. Psychiatriki. 2020;31:140-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bączyk G, Kozłowska K. The role of demographic and clinical variables in assessing the quality of life of outpatients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Med Sci. 2018;14:1070-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sabaz Karakeci E, Çetintaş D, Kaya A. Association of the Commitments and Responsibilities of the Caregiver Within the Family to the Disease Activity in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Report From Turkey. Arch Rheumatol. 2018;33:213-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gilliss CL, Pan W, Davis LL. Family Involvement in Adult Chronic Disease Care: Reviewing the Systematic Reviews. J Fam Nurs. 2019;25:3-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Qiao J, Zhou M, Li Z, Ren J, Gao G, Zhen J, Cao G, Ding L. Elevated serum granzyme B levels are associated with disease activity and joint damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520962954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shervington L, Darekar A, Shaikh M, Mathews R, Shervington A. Identifying Reliable Diagnostic/Predictive Biomarkers for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Biomark Insights. 2018;13:1177271918801005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jeong JH, Yoo WG. Effect of caregiver education on pulmonary rehabilitation, respiratory muscle strength and dyspnea in lung cancer patients. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27:1653-1654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yu F, Li H, Tai C, Guo T, Pang D. Effect of family education program on cognitive impairment, anxiety, and depression in persons who have had a stroke: A randomized, controlled study. Nurs Health Sci. 2019;21:44-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, Hotopf M. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis: reply. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:578-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ang DC, Choi H, Kroenke K, Wolfe F. Comorbid depression is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1013-1019. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Zhang L, Zhang T, Sun Y. A newly designed intensive caregiver education program reduces cognitive impairment, anxiety, and depression in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2019;52:e8533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Maxwell M. Targeted education for general practitioners reduces risk of depression or suicide ideation or attempts in older primary care patients. Evid Based Ment Health. 2013;16:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sun FK, Chiang CY, Lin YH, Chen TB. Short-term effects of a suicide education intervention for family caregivers of people who are suicidal. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:91-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dobkin BH. Clinical practice. Rehabilitation after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1677-1684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 587] [Cited by in RCA: 509] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kitts RL, Goldman SJ. Education and depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21:421-446, x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zhou B, Wang G, Hong Y, Xu S, Wang J, Yu H, Liu Y, Yu L. Mindfulness interventions for rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;39:101088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Polenick CA, Stanz SD, Leggett AN, Maust DT, Hodgson NA, Kales HC. Stressors and Resources Related to Medication Management: Associations With Spousal Caregivers' Role Overload. Gerontologist. 2020;60:165-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Youssef N, Mostafa A, Ezzat R, Yosef M, El Kassas M. Mental health status of health-care professionals working in quarantine and non-quarantine Egyptian hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26:1155-1164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Galo JS, Mehat P, Rai SK, Avina-Zubieta A, De Vera MA. What are the effects of medication adherence interventions in rheumatic diseases: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:667-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Minnock P, McKee G, Kelly A, Carter SC, Menzies V, O'Sullivan D, Richards P, Ndosi M, van Eijk Hustings Y. Nursing sensitive outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;77:115-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zuidema RM, Repping-Wuts H, Evers AW, Van Gaal BG, Van Achterberg T. What do we know about rheumatoid arthritis patients' support needs for self-management? Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1617-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Dures E, Almeida C, Caesley J, Peterson A, Ambler N, Morris M, Pollock J, Hewlett S. Patient preferences for psychological support in inflammatory arthritis: a multicentre survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:142-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Farley S, Libman B, Edwards M, Possidente CJ, Kennedy AG. Nurse telephone education for promoting a treat-to-target approach in recently diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis patients: A pilot project. Musculoskeletal Care. 2019;17:156-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Connelly K, Segan J, Lu A, Saini M, Cicuttini FM, Chou L, Briggs AM, Sullivan K, Seneviwickrama M, Wluka AE. Patients' perceived health information needs in inflammatory arthritis: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:900-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |