Published online Oct 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8312

Peer-review started: February 3, 2021

First decision: April 25, 2021

Revised: April 30, 2021

Accepted: August 27, 2021

Article in press: August 27, 2021

Published online: October 6, 2021

Processing time: 237 Days and 0.6 Hours

This paper aims to explain the construction of the autonomous subject from Foucault's ethical perspective for the qualitative analysis of interprofessional relationships, patient-professional relationships, and moral ethics critique. Foucault tried to break loose from the self, which is merely the result of a biopolitical subjectivation and constituted an interpersonal level. From this, different elements involved in the decision-making capacity of patients in a clinical setting were analysed. Firstly, the context in which decision-making occurs has been explained, distinguishing between traditional practices involved in self-care and the more modern conceptions that make certain possible transformations. Secondly, an attempt is made to explain the formation of the medicalisation of society using the transformations of what Foucault called "techniques of the self". Finally, the ethical framework for a subject's "self-creation", insisting more on the exercises of self-subjectivation, reinforcing the ethics of the self by itself, the "care of the self", has been explained. The role of the patient is understood as an autonomous subject to the extent that the clinical institution and the professionals involved comprehend how the patient’s autonomy in the clinical environment is constituted. All these elements could generate grounded theory on the qualitative methodology of this phenomenon. The current ethical model based on universal principles is not useful to provide a capacity for patients decision-making, relegating to the background their opinions and beliefs. Consequently, a new ethical perspective emerges that aims to return the patient to the fundamental axis of attention.

Core Tip: The current model of decision-making for patients in the clinical setting has major limitations. A new perspective using the concepts of Foucault's ethics from grounded theory allows to analyse the phenomenon and propose changes. From a critique of principlist ethics, this study attempts to configure elements of analysis to build a new theory on how professionals should act to achieve real self-determination of patients in decision-making.

- Citation: Molina-Mula J. Grounded theory qualitative approach from Foucault's ethical perspective: Deconstruction of patient self-determination in the clinical setting. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(28): 8312-8326

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i28/8312.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8312

Although numerous studies have evaluated decision-making in clinical practice, they focus on decision-making in a shared way, and the short-term results[1] focused on the cognitive or affective effects of the patients but not accepting ethical arguments or rational evidence[1,2]. This suggests the necessity to consider long-term consequences, including interventions, patients, teams, organisations, and health systems[2].

Most of the investigations are directed towards the interaction of professionals with patients, often without considering factors at the level of interpersonal relationships or the health system model[3-5]. This illustrates a very reductionist perspective on the decision-making capacity of patients. Some authors[6] indicated the necessity for a deeper approach from new perspectives that raise key points, such as evaluating the quality of a decision-making process addressing the ambivalence that emerges when these perspectives are recognised.

The duality between the so-called mandatory autonomy that defends self-determination vs the optional autonomy, which is more established in our health model, is in constant discussion due to the results or consequences that each of these generates in decision-making[7,8]. In terms of cognitive-affective results, psychological clarity or recognition of the emotional work inherent in choosing between several alternatives has not yet been resolved[9]. Even in recent decades, various tools or methods of communication from professionals to patients and families have been designed to ensure the latter's autonomy[10]. The Mayo Clinic conducted few studies with observational measures and informed consent through conversational interaction strategies between professionals and patients[11].

Even a systematic review by Michalsen et al[12] highlights that decision-making models in settings such as the intensive care unit (ICU) should be based on exploring interprofessional relationships to favour inter- and intra-team communication, the central axis of Foucault's analysis and power relations.

All these attempts standardise the quality of health decisions. Still, they have not allowed progress in the real self-determination of patients beyond the ability to choose according to professional preferences[13]. Even then, it should be mentioned that there are more than 100 clinical trials evaluating decision-making aids that seem to increase the participation of patients in this decision-making with an increase in their degree of satisfaction[14]. As the most significant barriers, apart from lack of time and resources, professionals' attitudes are considered the key factor[15,16].

Elwyn et al[6] and Carman et al[17] concluded that much is known about shared decision-making between professionals and patients. Still, there is very little approach from a patient’s self-determination perspective in ethical deliberation. From this premise, the need for self-determination of patients is addressed, undoubtedly taking into account all the questions that arise in its real implementation in the practice of decision-making in the clinical field.

Lindberg et al[18] considered that the first factor of analysis arises when self-determination is offered to the patient. The professionals consider the patient sufficiently prepared to decide or a circumstance that they believe the patient should decide. This temporary aspect is considered an annulment in the patient's ability to make decisions as a professional's choice.

The problem is that until timing becomes an option from the moment a professional concludes that a patient will have to make decisions, this capacity is completely nullified[19]. They can be minor routine problems or much more relevant.

Self-determination has been conceptualised but little investigated, affected by traditional paternalism[18] as indicated among other reasons along with legitimisation of limiting freedom through the defense of prospective self-determination by considering the professional where the patient, in the future, might prefer another decision, is contradictory, even if it is good for the patient. Our responsibility to respect others must be durable in time to achieve real self-determination and not in a portion of time[20-22], as defended by Foucault's proposal of the subjective construction.

In a hospital, it is necessary to check the connection between the patient’s autonomy and exercise power in daily practices to understand and articulate Foucauldian ethics. For this reason, the mechanisms and procedures in the exercise of normalisation strategies, homogenisation, impositions, restraints, oppressions and knowledge that determine the patient's autonomy capacity in making decisions must be analysed.

The perspective of the Foucauldian ethics analyses the autonomy based on the codes that currently configure the behaviours allowed or forbidden instead of personal choice that opens a new possibility of understanding ethics. This analysis allows establishing a new way of understanding the subject as being autonomous. Constructing a new way of understanding ethics is important in clinical settings as it provides fundamental competencies in patients' decision-making and breaks the current limitations.

A significant number of studies have reported the patient’s autonomous decision-making, although they have dealt from different angles and ethical approaches. Health care professionals consider it a significant aspect of practice, and debate on this aspect is ongoing among the experts[22-28].

Some authors share that the patient’s decision-making is halfway at the crossroads between two ethical positions: Paternalism and informed choice[23-25]. In the paternalistic models, the health care professionals decide on behalf of the patient based on the best discourse they do for them, which could mean a breach of respect for the patient's autonomy. Whereas in the informed consent-based models, the health care professionals provide the patients with information and then make their own decisions. This position raises several ethical dilemmas: on one side, when the patients want to receive the complete information about their health problem before granting any consent; on the other side, the role of the patients family in the decision-making process[8,9,27].

According to some studies[28], a culture of domination prevails among the North American and European professionals in the clinical setting, trying to generate a type of patients that follow the medical paradigm. Some investigations[29-32] raise different cultural conceptions on the patient’s informed consent and the family’s part in decision-making.

Several authors classify differences in the patient’s decision-making into restrictive or open conceptions. Both conceptions have been related to the ethical positions indicated above. The restrictive conception responds to a paternalistic attitude and the open conception with the patient's informed choice[23,33,34], allowing us to examine the tensions between both.

Regarding the more restrictive conception[23], authors indicated the following: (1) Patients had got their preferences for their medical care, and obtaining those preferences and taking decisions are the responsibility of the health care professionals; (2) Professionals respect the patients informed autonomy of making the best decision to meet the best possible clinical results; and (3) Patients and professionals can, and sometimes must, discuss the preferences. However, the process must conclude with a choice based on scientific evidence and the professional’s expertise, taking into account the patients preferences.

Joseph-Williams et al[35], Epstein and Peters[36], Nelson et al[37], as well as Sevdalis and Harvey[38] claim that professionals might misunderstand this proposal. They use their privileged situation to build up the patients preferences based on domination and their own preferences without establishing an equal relationship with them[39]. This could decide the type of relationship between the professionals and patients for autonomous decision-making.

Carrying on with the restrictive perspective, health care professionals do not consider that all patients' preferences have the same value or should be taken into account when making decisions, placing some needs ahead of others[40]. Walker[40], and Cribb and Entwistle[23] consider this a drawback for the professionals when promoting a person’s autonomy. In addition, in an evidence-based model, the health care professionals seek a consensus among the preferences of patients, making a choice based on their values; but intend to emphasise the predictable clinical results to make a decision.

In a clinical setting, the ideas of the professionals working with the patients are crucial in any decision-making process. The restrictive perspective of this process stands for the option of negotiating with the patients in some cases, but not always[23]. Authors suggest that professionals and patients should only discuss the health care options together if the patients want to decide based on the effects of different options, according to scientific evidence and their preferences. The option of deciding together always depends on ensuring that their best or most beneficial option is chosen[41]. Wirtz et al[42] argue that the patients would only share their preferences based on the expert knowledge of the professionals, who normally discuss the appropriate options according to the scientific evidence.

Many authors consider this restrictive perspective an excessively simplistic approach[23-25,41] despite being the most established clinical practice.

The open guidance on the patients' decision-making, although on a theoretical level, is the most widespread one, showing certain limitations regarding operability on a practical level[23,43]. The starting point is the perception that the relationships between professionals and patients are different from other kinds of social relations. Emanuel and Emanuel[44] already suggested that relationships between professionals and patients are normally fixed and marked by the role of each professional in the health care team. Professionals follow technical aspects or protocols for the action, combining with the limited knowledge of the patients for their care. Therefore, in the decision-making process, it is essential to consider the inter-professional relationships and roles of professionals to understand the relationships between them.

The open perspective considers that it is possible to use the expertise of professionals to help patients reflect and adapt their preferences as a part of their autonomous decision-making while avoiding standardised, and institutionalised rules[23]. These authors pointed out the need to analyse the power structures in the relationship between professionals and patients and how they impact the vulnerability of the autonomy of patients.

In decision-making both the restrictive and the open perspective confront; the ethical commitment between a paternalistic or an open approach basically depends on the individual skills of health care professionals. Identifying these relationships will contribute to avoiding the excessive and dominant use of power. In addition, creating a suitable environment allows the development and practice of the qualities of professionals and the capabilities of patients[13].

Several studies illustrate that the autonomy and self-determination of patients are rarely prioritised by professionals, who even reject those patients and demand more information as well as power for decision making. The professionals prefer clinical aspects rather than the autonomy of patients[26,29,45]. Hence, fixed and confined health care is established, which is completely institutionalised, leading to the behaviour of the patients[46-50].

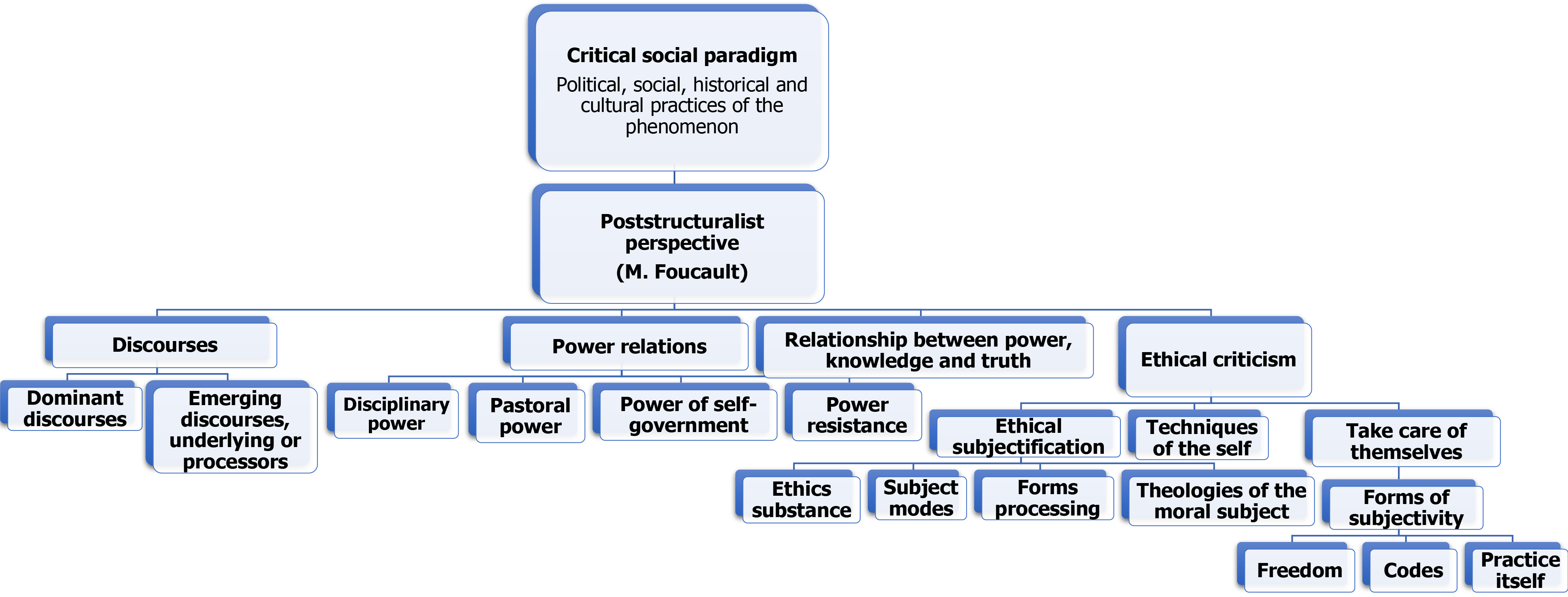

Based on the criticism of the current ethical model in the clinical setting from the perspective of Foucault, this study aims to analyse the autonomy of patients in decision making and the influencing factors (Figure 1).

From Foucault's point of view, society's medicalisation is structured like a real technology of the social body, thus playing a decisive part in the biopolitical production of society. The population is a theoretical problem but a technical dilemma that demands procedures of intervention and modification[51].

This incursion of power in life is what Foucault called “biopower”[52]. This is understood as a societal control mechanism for people's lives[53] and refers to the exercise of power at economic, historical and social levels and consigns biological life as a political event. In a clinical setting, this biopower is expressed as a set of techniques and strategies expressed in statistics related to health, development and care costs[21].

According to Dzurec[54], a connection between medicine and family reorganises family life in three dimensions: (1) The family is transformed into a privileged biopolitical system, a perfect tool in health administration, where the construction of social dwelling as a health space is encouraged. In the age of biopolitics, the family works as the preservation, control, and life production mechanism; (2) Hygiene acquires a connotation of a public issue, associated with epidemics, morbidity, average life span and mortality. The implementation of a community health system consolidating the state of collective hygiene is fundamental; and (3) Authors instructed an administrative physician is acting as the original nucleus of social economy and sociology and establishing the organisation of a political-medical area of influence on the population with prescriptions focused on diseases and behaviour. These aspects explain the social medicalisation and creation of a medical-administrative system, promoting social control.

A therapeutic framework with a new design of the hospital environment comes into existence. It consists of creating an individualised space around every patient, which is adjustable following the disease development and concentrates absolute power within the clinical organisation in the hands of physicians. Also, generating a permanent record of all the events is critical for producing specific knowledge[53]. Thus, modern medicine is a social medicine configured as the technology of a social body.

Foucault[55] describes three models developed in different European countries: The medicine of the State, urban medicine, and the labour force medicine. The medicine of the state is an exhaustive observation of morbidity, the normalisation of medical practice and knowledge, and the creation of an administration to control clinicians and medical bureaucrats. The medicine of the labour force is the transformation of the population into a more appropriate and long-lasting labour force and an innocuous political force indicating no threat to the bourgeoisie. To refine the quarantine scheme, the urban developed the concept of environment and health[55].

According to Foucault[55], these models caused four modifications in society’s medicalisation. Firstly, the State has to ensure people's health in the interest of preserving their physical strength, labour force, and production capacity, turning the rights of humans to maintain their bodies in good health due to State's action. Secondly, the preponderance of the hygiene concept considering the relationship between the individual and the State. Thirdly, the expenses assigned to health care, the cost of labour interruption, and the calculation of the risks affecting the individual's physical well-being determine a new level of concerns in the field of macro-economy. Lastly, health becomes a focus of political struggles and debates.

All these aspects demonstrate the extent of the medical paradigm in contemporary culture due to the incorporation of medicine in the biopolitical mechanism. According to Foucault[56], body care, physical health, and the concern about illnesses prove to be especially decisive in such a regime.

Medicine has acquired an authoritarian power with normalising functions, which widely exceeds diseases and the demand of patients[56]. Physicians and their knowledge are the key parameters for the invention of a normalised society. Thus medicine is no longer a mere instrument of the economic system; it has entered and turned into one of its components. Hence its appreciation changes and health becomes a consumer item. Health has entered the trading game with laboratories, pharmaceutical companies, physicians, clinics and insurance companies as production agents and real patients and potential ones are its consumers. Physicians become the core agents of medicalisation, the simple distributors of drugs in a market of suffering and promised health.

The medicalisation of today’s society is independent of medicine, medical officials and health institutions since their logics run all over society as a commodity. Biopolitics has used medical discourses and technologies, family intervention, hospital structures and consumption systems to conquer new forms of political appropriation of life[57].

This control of society through the medicalisation of life has also influenced the applicability of bioethics in the health field. Bioethics has become a mere logical instrument for applying a series of universal principles based on efficiency, consistency and application criteria[58]. Many authors refer to this conception as principialism[59-63].

Some authors have defined this principlism as legitimising a biomedical discourse or an “oppressive status quo” of principles[49]. McGrath[64] has indicated that the currently advocated bioethical model uses principles that create an illusion about the autonomous decision-making capacity of patients. Principles give sense to the meanings and values of a health care institution which defines, describes and limits what can or cannot be done. In other words, these principles provide the descriptions, rules, permissions and prohibitions of social and individual actions[17,46].

From the Foucauldian ethics, the main criticism towards principlism is based on the idea that the resolution of ethical conflicts is referred to professional experts in this area, without considering the patient’s opinion, autonomy, and capacity for decision-making. This is the reason that critical ethics suggests a bioethical reflection based on the power and its effects on neutralised discourses superseded by the experts in ethics[65].

This gives room to an ethical trend that advocates that, without an analysis of power and its complexities, bioethics cannot consistently examine the social, political and even economic aspects of ethical conflicts[58].

Thus the concept of power develops in the discourse of ethical-critical reasoning, which moves away from the idea of valuing principles above the context and routes towards a discursive understanding of autonomy. It deals with examining how personal choice is the reality built by several health organisations. Critical ethics suggests that the substantial rationalism of principlism must be challenged by the contextualisation process of the bioethical problems from the power and the discourse[64].

Therefore ethics should depart from the point that there is no clear and distinctive idea expressed by the structuring of principles[64,66]. The ethical response does not consist of applying certain principles in difficult situations but rather interprets service provision where ethics expresses the organisation discourses.

For this reason, it is important to introduce the Foucault’s concept about biopolitics and its implication on ethics. Biopolitics arises from the analysis as a principle and a method of rationalising the exercise of government and breaks the “reason of state”. The rationalisation of governmental practice implies paying attention to control, regulation, supervision, order and administration[67].

Ethical practice is intended to offer alternative actions and respect for individual subjectivity. This gives rise to a concept of Foucauldian ethics based on the indivi

In a clinical environment, Foucault's ethics is understandable as the dimension of the relationship between the real behaviours and the codes or systems of prohibitions, prescriptions and assessment. These determine representing a person as a moral individual who sets the forms or modes of subjectivation[68].

In the first of these forms of subjectivation, the philosopher describes the response to the technologies, where caring tries to eliminate what we depend on and re-position us in the world as causes and effects.

The second form of subjectivation is the codes. Foucault defines these forms as historical structures representing the individual as the subjects of their actions and not mere agents. At this point, a serious question arises about the requirement of universality in the historical construction of ethics. Its ethical concept, not organised as an authoritarian, unified moral, equally imposed on everybody, gains strength. Foucault suggests non-universalising, non-normalising ethics without a disciplinary structure and not based on scientific knowledge.

In the final form of subjectivation, Foucault considered defining the culture of the self, the social practices as practices of the self[69]. Foucault talks about the independence or relative autonomy of the relationship with oneself regarding the codes. He considers that the individual materialises and establishes a moral individual, a struggle for freedom and a victory to obtain the command[70].

This command overflows through many different doctrines, adopts the form of an attitude that permeates the ways of life and articulates in a set of procedures and exercises which can be meditated and taught, representing a practice which develops even interpersonal and institutional forms and giving a place to the production of knowledge[71].

According to Foucault, medical care takes intense attention to the body, especially when both kinds of diseases, those of the soul and body, can communicate mutually. This transference represents a point of the individual's fundamental weakness[69].

Thus, it is necessary to find the existing connection between the patient’s autonomy and the professional's exercise of power by analysing the relationship between them and their backgrounds. Therefore an analysis of the discourses and the power relations are embedded in the daily practice of the health professionals in their relationship with the patient, the family, and the health care system of the health care professionals allows articulating Foucauldian ethics.

Departing from considering power as a strategy exerted and present in all social practices, although sometimes easily recognisable, it is not always clearly visible in a clinical setting because of its subtle exertion through persuasion and manipulation. Power is expressed in strategies of normalisation, homogenisation, impositions, subjections, oppressions, times, spaces and the knowledge which operate in professional relations and the background of the professional practice.

In decision-making, this analysis can identify the legitimacy of certain ways of the action of nurses and behave before the patient's autonomy. It is important to make visible what discourses dominate the professional practice and identify the transforming or emerging discourses that seek to open up alternatives of significance, understanding and action to the naturalised discursive practices in the profession and the current health system, as new Foucauldian ethics.

Foucault[67] presents the importance of power relations in the knowledge generated from different disciplines. Each discipline builds unequal positions for exerting power by placing some in a more privileged position than others.

In the epistemological ladder of professional knowledge as a minor science, nursing is considered, which has led to marginality and a maternal stereotype of the nurse vs the dominant or major science of medicine[72]. These aspects determine that the physicians are related to their hegemony in the health field. By referring to the nurse, the role that she acquires in the physician's context is dominated.

This analysis shows different kinds of power strategies, from the more emotional or therapeutic ones to self-management or the more self-applied or subjectivised ones.

The perspective of the Foucauldian ethics allows an analysis of the professional relationships based on the codes that determine what behaviours are permitted or forbidden in the professional practice, vs a person, neither tough nor standardised choice, which makes understanding ethics. This means analysing those elements which cause nurses to move away from understanding the value of a set of principles above the context and moving towards a discursive comprehension of the autonomy of patients[64].

The French philosopher not considered the subject as a fundamental point if the result of a subjectivation process involves a set of particular practices and techniques. Foucault tried to break loose from the “self”, which is merely the result of a biopolitical subjectivation and constituted an interpersonal level, an “ethic of the self” as a point of resistance to disciplinary power. So, subjects come to recognise themselves as subjects of knowledge, of power relations and ethical relationships to the self[73].

Podsakoff and Schriesheim[74] associated this power directly due to an interpersonal relationship where the influenced subject is recognised as a referent that influences and seeks closeness with him/her. Laswell and Kaplan[75] directly relate power to participate in decisions, where the adoption of decisions constitutes this interpersonal process, and therefore, power represents an interpersonal relationship. Hence it will be a critical element in the analysis of the ability to patient’s decision making.

Foucault holds that the idea of constituting ethics of the self-conceived is an art of resistance to biopolitical normalisation. Thus philosophy as part of the self becomes a key element in the struggle that involves the resistance to normalisation and forcing the individual back to himself/herself and tying him/her own identity in a constraining way[76,77].

The philosopher points out that ethics focuses on the following propositions: the core of philosophy is ethics; freedom is the foundation of ethics; ethics revolves around the subjectivation techniques or the care of oneself. So ethics as the care of oneself can be created about one's own existence; makes a person stronger for political resistance; involves the willingness to care for other human beings.

For Foucault, the ethics of subjectivation arises from the ethical substance, the subjection modes, the forms of development, and the moral subject's teleology; and all these are explained in greater depth.

Foucault talks about the substance of ethics as the subject's proper transformation from his/her historical and social context[78]. Ethics substance forms part of the individual who must establish themselves as the main subject of their moral behaviour, which makes up their feelings and different ways of working of the moral subject. Therefore, it is proposed to consider the patient's beliefs, values, and preferences to construct a free subject in the decision-making process to apply the ethical substance.

The subject modes define the subject's relations with rules and how the subject recognises those rules as obligations within a particular social and cultural context. These modes are the norms and codes established in the health institutions that set the pace of the decision-making process. Thus, the patient's relationship with the rules established in the clinical setting is configured through the subject modes. The determination of what the patient can and can not do and what decisions correspond to their care with the permission of the professionals and the institution are important.

Foucault calls forms of elaboration or ethical work. As individuals in a society, we are determined by social, political and cultural norms and, therefore, as institutional norms configure patients. These norms, obligations and codes determine the transformation of the patient into a moral subject, responsible for his/her own behavior as he/she is allowed to be in one way or another. From this, the relationship between the subjects transforms into a moral individual with his/her own behaviour.

This ethical work arises from learning the pre-established social rules, the control those rules have on the subject's behaviour and the subject's own struggle against those rules when his/her wishes and health are at stake. Thus the role played by the individual as an autonomous and free subject is understood -teleology of the moral subject.

Foucault refers to the moral subject's teleology as the final result of the established social rules and standards that produce a specific mode of being. However, he does not consider that this result involves strict obedience to the set rules, but establishing a relationship with oneself leads to a new behaviour[79].

In addition, Foucault introduces the technologies of the self as a basic and central element of ethical development. He suggests how people in every society use techniques which allow the individuals to perform a certain number of operations on their own bodies, souls, thoughts and behaviours by their own means. The subjects do independently, change themselves, and reach a certain level of perfection, happiness, purity, and supernatural power.

The self's technologies determine how people's actions and behaviour concerning the rules, regulations, and codes imposed on them will finally be. Then the subjects distinguish between the codes, determining what actions are allowed or prohibited and the codes, which determine the positive or negative values of different possible behaviour[80]. This distinction configures the kind of relationship one should have with oneself, which determines how it is supposed that the individual establishes himself/herself as a moral individual of his/her own actions[67,71].

This relationship with oneself introduces four major aspects: (1) What part of myself or my behaviour concerns moral behaviour, which in our society configures the main command of morality, the feelings; (2) The way how people are invited or encouraged to accept their moral obligations; (3) The self's auto-determination refers to what measures help us transform ourselves into ethical subjects. This means the ethical substance which moderates our actions and deciphers what are; and (4) What kind of being do pursue when subjects act morally, called “telos” and related to the effective behaviour of people with the existing moral codes on the one hand, and the relation of oneself with these four aspects on the other side[80].

Foucault refers to these positional changes as the techniques of the self, which the patients set in motion once hospitalised, ensuring their integrity and autonomy in making decisions about their own body and behavior[81]. The self's technologies determine how patients' acts and behaviour will ultimately be about the rules, norms, or codes imposed on them[80]. This behaviour will be free and autonomous, as far as the subject can understand how he/she is supposed to establish themselves as a moral individual of their own actions -technologies of the self.

Thus it is not enough to say that the subject establishes himself/herself in a symbolic system. The subject does not establish themselves in symbols but in real, historically analysable practices[80].

Finally, two concepts should be mentioned to analyse the Foucauldian ethics from the care of the self: the culture of the self and the culture of freedom.

The care of the self is a permanent, life-long practice that tends to ensure the continuous exertion of freedom[82]. It is about freeing ourselves from the set rules -subjection mode- to access our own behaviour or subjectivation technique. This means the proper care of oneself and the proper way of life.

Distinguishing between traditional practices involves self-care and the more modern conceptions that make certain possible transformations. From this construction of the subject, the different elements involved in the decision-making capacity of patients in a clinical setting are analysed. Firstly, the context in which decision-making takes place is explained. Secondly, an attempt has been made to explain how the medicalisation of society has been produced through transformations of being, using the "techniques of the self" as referred by Foucault. Finally, the ethical framework for a subject's "self-creation" is explained, which insists more on the exercises of self-subjectivation, reinforcing the ethics of the self by itself, the "care of the self".

All this configures the culture of the self or how we get rid of the established rules to access our own behaviour or subjectivation. This means our own way of life, its own subjectivation technique, and no prescription[83,84].

The institution determines the manners of subjection to which the patient is submitted to construct the self. It could be indicated that the patients find themselves immersed in the complex machinery of the clinical environment. The obligations imposed by the institution become a way of subjection for the full autonomy pursuit of patients. In their political discourse, the professionals and clinical institutions advocate the idea of patient-centred care quality. When analysing the quid of the institution, it is discovered that professionals do not get a message of quality objectives but, on the contrary, focused on optimising financial resources.

The initial message becomes an element of fictitious political marketing and generates a health organisation that commercialises health, a direct consequence of the effect of biopolitics on health. This situation makes the nurse feeling disappointed, unmotivated, frustrated and lacking future projection, even resigned to believe that there is no way to change it. All the above conveys that the management bodies are considered distant without any practical utility[85].

The institution’s exercise of power generates a more subtle process called colonisation or instrumentalisation of the health system, as proposed by some authors[22,86]. This process is nothing more than the normalisation of clinical practice using standards and protocols, collaterally generating internal relations between professionals, which are very rigid and based on the hierarchy of professional categories.

These two elements, normalisation and institutional market ethics, help generate the concept of a dominated patient in a health organisation, subject to the rules, schedules, available resources, and, therefore, keep to patients, without any possible decisions. At this level, the patient’s autonomous capacity is completely invalidated.

In light of the patient’s domination, several challenges for health institutions arise, which open up space where the participation of patients in decision-making can be real. Gilbert[87], Osborne[88] and Beresford[89] advocate for reducing bureaucratic complexity reconsidering the objectives of the health system focused on the patient instead of the market values and opting out of consumerism as the economic value of care. This perspective would respond to the use of technologies that allow reconstruction of the patient's autonomy, as it is presently understood, to give way to self-determination. Thus the Foucauldian ethical study becomes important when constituting the patient as an ethical individual in his/her relation with the institution to set his/her behaviour or, as the telos of the relationship referred by the French philosopher[55].

The inter-professional relationship is another key factor that defines the patient's participation and power rates as the subject. According to several professional stereotypes, the healthcare team is configured to focus on physical and clinical complications. Medical criteria dominate the practice of other professionals, where the physician orders and the nurse executes. In other words, the physician exerts an absolute power, and the nurse is a subtle and often a silenced power.

This interaction between power and scientific knowledge relegates decision-making to the patient, as far as the professionals leave him/her, and ineffective communi

It could be that the improvement in communication between professionals, training for communication abilities and the reorganisation of professional skills challenge the enhancement of inter-professional relations and teamwork[26]. These challenges and examining the dynamic relationship between scientific knowledge and power[90] produce resistance to reverse the limitations in the patient’s autonomy[91,92].

According to Foucault[56], the science or scientific truth model determines the construction of one discipline dominating the other, as in medical science and nursing. This truth establishes the norms a patient could submit to when visiting the hospital and accepting the game's rules.

Thus professionals and institutions provide the truth to the patient's normality, establishing a manner of subjectivation in the clinical setting. This approach to the productive dynamics of power helps to make visible the mechanisms and strategies of knowledge performed by the professionals as a set of forces that passes the patients, producing and using them. This explains why the power exerted by the professionals over the patient through persuasion, confidence, and paternalism results in patients as products and prescribes certain models of speech, behaviour, and organisation of care without considering the patient’s criteria[93].

On the relationship between nurse and patient, several opportunities of technologies of the self are outlined to enhance the latter’s capacity to make decisions. However, few asymmetrical power relations appear, where the nurse creates one space of participation or another, depending on their attitudes and the one perceived from the patient. Participation is understood not as a real power of decision but as a limited degree for the patient to decide about some aspects of patient care. Even if the nurse prefers a patient who goes with the flow, is compliant and cooperating with the prescribed care, this strategy shows the greatest benefit for the patients. They will be informed and active in their care, maintaining a good relationship with the nurse.

The nurse recognises the ongoing socio-cultural shift as to the kind of patient who attends the health system. Nurses think that patients need to be better informed, and if patients are not, they ask for it and claim higher levels of participation and power of decision[94].

These transformations meet Foucault’s premise that where there is power, there is resistance. Thus the power of the professionals and the institutions finding their limit in the patient’s resistance and care of the self. In this way, professionals and institutions design a profile of struggle, incorporating tactics of this power as a base to justify certain behaviour of the nurse, such as persuasion and coercion, when faced with the patient’s rejection and refusal of the proposed care.

The danger of any relationship of power is the possibility that it solidifies in a kind of domination[77]. In this case, the real task of the nurse is to constantly defend and reaffirm the transformations in the patient’s power of decision to maintain the patient’s autonomy; therefore, the need for ethics conceived as the care of freedom arises[57].

The Foucauldian ethics suggests a resistance to the relationship framework between knowledge, power and subjectivity, currently imposed in the clinical setting. It could be accepted that the patients can exercise power over them, of the construction and the creation of their care. Then the care of the self as a practice between the professionals and the patients appears to avoid the shift in domination[95].

To articulate the proposal of Foucauldian ethics with the results obtained from an earlier study[94], with the assistance from professionals, the patients need to detach from the imposed constraints to gain the freedom of decision on their care.

From this perspective of ethics as freedom and culture of the self, it is key to consider patients' feelings, beliefs, and values before making any decision about their care. This ethical work emanates from pre-established norms of the control of rules about the behaviour and struggles of the patients against these rules when their health is at risk.

Care of the self would materialise through breaking with established norms and exercising the patient's freedom. That is, a capacity to make real decisions about the patient's care, where the professionals are simply guides. A professional allows the patients to make their own decisions based on their beliefs and values among the different possibilities.

For example, in a situation where the patients must choose between performing a surgical intervention or not, the professionals must provide the alternatives, explaining the risks and benefits and finally respecting the patient's choice, even if it is not the best for the professionals or the most beneficial. Therefore, the patients must make their criterion prevail as an inherent right and resist the persuasions of the professionals.

Although defended by principialist ethics in its principle of autonomy, this proposal is confined to a series of limitations such as life-threatening risks, risks to public health, and mental incapacity. In addition, the influence of the principle of beneficence prevents the professionals from considering that decisions that are not the most beneficial are based on the rejected clinical criteria. The patients are not persuaded to choose them.

If applied, in this case, principlist ethics, the decision before a conflict of opinions between the patients and the professionals, would value the risks and benefits for the patients. Although it would take into account the opinions and values, professionals would take a back seat, and in the final decision, the clinical criterion would prevail.

From this, the patients establish a new behaviour, which frees them from the strict compliance of the game rules in a clinical setting, not to work against them, but to adapt them to the decisions regarding their health.

It could be that the forms of constraints established in the clinical setting cannot be eradicated. Still, the patient’s exercise of autonomy must emerge from the strategies and a shift in certain forms of institutional domination.

Likewise, institutions should avoid the solidification of dominating power, configuring the patient as a passive care objective. It cannot be expected that each patient, from his/her own ethics, assumes a common, universal and strict criterion, as the institutions pretend. Breaking with this homogenising dynamics of the clinical practice and universalised ethics will encourage the patient’s autonomy in decision-making.

The originated debate on freedom and domination methods requires a practical consideration of care of the self and, therefore, a culture of the self. The current method of ethical decisions based on the universalising desire of utopia should be substituted by altering the limits imposed on the patients and enhancing the possibility of freedom.

Ultimately, the opportunities unfolding in the patient’s autonomous decision-making, according to the perspective of the Foucauldian ethics, are based on recognising the patient’s personal decision by the clinical institutions and professionals. For this purpose, universalising, normalising, and per se legal moderation styles should be opted out with a disciplinarian structure and scientific knowledge. As long as professionals do not break free from the obsession with exerting power within their inter-professional and patient relations, they will still be entangled in the knowledge-power complexes that generate the control of people as bodies or as the population with no personal identity[70].

A patient’s independence or autonomy about professionals and the institutions will constitute a free moral subject and a victory over the dominating rules[95]. The patients exercise autonomy in a real clinical context, which participates as before and decides on all the received care[78].

It has been shown that the main subjection modes in patient’s autonomy in a clinical setting are the standards of the health institution, the exercise of a hegemonic power in the relationships between professionals and the asymmetry in the relationship of professionals with the patients.

In addition, the current ethical model based on universal principles is not being useful to provide a capacity for patient decision-making, relegating to the background their opinions and beliefs.

Consequently, a new ethical perspective emerges that aims to return the patient to the fundamental axis of attention. It proposes to break with the discourse of patient-centred care or patient that participates in the decisions so that it is a subject that decides what should be done and how to do it with the help of the institution and the professionals. An institution that belongs to the user and professionals who work for a patient.

Therefore, this change will not be possible without the professionals committing themselves to help strategies or technologies to allow the patient to resist and modify the current regulations and impositions. It will not be possible without the professionals contributing to the patients building a culture of the self in the health institution.

These key concepts of the Foucaultian ethics of power, technologies of the self and care of the self allow developing a grounded theory on qualitative methodology to analyse patient self-determination in the clinical setting.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medical ethics

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bi LK S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Légaré F, Stacey D, Turcotte S, Cossi MJ, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID, Lyddiatt A, Politi MC, Thomson R, Elwyn G, Donner-Banzhoff N. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD006732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ballard-Barbash R. Multilevel intervention research applications in cancer care delivery. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012:121-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, Mann M, Edwards AG, Clay C, Légaré F, van der Weijden T, Lewis CL, Wexler RM, Frosch DL. "Many miles to go …": a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alexander J, Prabhu Das I, Johnson TP. Time issues in multilevel interventions for cancer treatment and prevention. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:526-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 806] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 50.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Elwyn G, Frosch DL, Kobrin S. Implementing shared decision-making: consider all the consequences. Implement Sci. 2016;11:114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schneider C. The practice of autonomy: patients, doctors, and medical decisions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. |

| 8. | Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Arora NK, Ganz PA, van Ryn M, Mack JW, Keating NL. Association of Actual and Preferred Decision Roles With Patient-Reported Quality of Care: Shared Decision Making in Cancer Care. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:50-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sepucha KR, Borkhoff CM, Lally J, Levin CA, Matlock DD, Ng CJ, Ropka ME, Stacey D, Joseph-Williams N, Wills CE, Thomson R. Establishing the effectiveness of patient decision aids: key constructs and measurement instruments. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Newell S, Jordan Z. The patient experience of patient-centered communication with nurses in the hospital setting: a qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13:76-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wyatt KD, Branda ME, Anderson RT, Pencille LJ, Montori VM, Hess EP, Ting HH, LeBlanc A. Peering into the black box: a meta-analysis of how clinicians use decision aids during clinical encounters. Implement Sci. 2014;9:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Michalsen A, Long AC, DeKeyser Ganz F, White DB, Jensen HI, Metaxa V, Hartog CS, Latour JM, Truog RD, Kesecioglu J, Mahn AR, Curtis JR. Interprofessional Shared Decision-Making in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Recommendations From an Expert Panel. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1258-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | O'Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Moulton BW, Sepucha KR, Sodano AG, King JS. Toward the 'tipping point': decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:716-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L, Wu JH. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD001431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 566] [Cited by in RCA: 854] [Article Influence: 77.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, Stobbart L, Tomson D, Macphail S, Dodd C, Brain K, Elwyn G, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ. 2017;357:j1744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, Aarts J, Barr PJ, Berger Z, Cochran N, Frosch D, Galasiński D, Gulbrandsen P, Han PKJ, Härter M, Kinnersley P, Lloyd A, Mishra M, Perestelo-Perez L, Scholl I, Tomori K, Trevena L, Witteman HO, Van der Weijden T. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;359:j4891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, Sweeney J. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 872] [Cited by in RCA: 1008] [Article Influence: 84.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lindberg J, Johansson M, Broström L. Temporising and respect for patient self-determination. J Med Ethics. 2019;45:161-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Henrikson NB, Ellis WJ, Berry DL. "It's not like I can change my mind later": reversibility and decision timing in prostate cancer treatment decision-making. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:302-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ahlin J. The impossibility of reliably determining the authenticity of desires: implications for informed consent. Med Health Care Philos. 2018;21:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Molina-Mula J, Peter E, Gallo-Estrada J, Perelló-Campaner C. Instrumentalisation of the health system: An examination of the impact on nursing practice and patient autonomy. Nurs Inq. 2018;25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Molina-Mula J, Gallo-Estrada J. Impact of Nurse-Patient Relationship on Quality of Care and Patient Autonomy in Decision-Making. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cribb A, Entwistle VA. Shared decision making: trade-offs between narrower and broader conceptions. Health Expect. 2011;14:210-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Iliopoulou KK, While AE. Professional autonomy and job satisfaction: survey of critical care nurses in mainland Greece. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:2520-2531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Entwistle VA, Carter SM, Cribb A, McCaffery K. Supporting patient autonomy: the importance of clinician-patient relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:741-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Duke G, Yarbrough S, Pang K. The patient self-determination, act: 20 years revisited. J Nurs Law. 2009;13:114-123. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Calloway SJ. The effect of culture on beliefs related to autonomy and informed consent. J Cultural Diversity. 2009;16:68-70. |

| 28. | Antoun JM, Hamadeh GN, Adib SM. What matters in the patients' decision to revisit the same primary care physician? J Med Liban. 2014;62:198-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fiester AM. What mediators can teach physicians about managing 'difficult' patients. Am J Med. 2015;128:215-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Griffith R. District nurses' crucial role in identifying unlawful deprivation of liberty. Br J Community Nurs. 2014;19:239-240, 242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Paput A. Therapeutic education, a factor of compliance and autonomy. Rev Infirm. 2014;24-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | McKinnon J. Pursuing concordance: moving away from paternalism. Br J Nurs. 2014;23:677-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Moumjid N, Gafni A, Brémond A, Carrère MO. Shared decision making in the medical encounter: are we all talking about the same thing? Med Decis Making. 2007;27:539-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:301-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1023] [Cited by in RCA: 1065] [Article Influence: 56.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Elwyn G. Power imbalance prevents shared decision making. BMJ. 2014;348:g3178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Epstein RM, Peters E. Beyond information: exploring patients' preferences. JAMA. 2009;302:195-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nelson WL, Han PK, Fagerlin A, Stefanek M, Ubel PA. Rethinking the objectives of decision aids: a call for conceptual clarity. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:609-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sevdalis N, Harvey N. Predicting preferences: a neglected aspect of shared decision-making. Health Expect. 2006;9:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sen A. Rationality and freedom. Cambridge MA: Belknap Press, 2002. |

| 40. | Walker RL. Medical ethics needs a new view of autonomy. J Med Philos. 2008;33:594-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Stevenson C. Theoretical and methodological approaches in discourse analysis. Nurse Res. 2004;12:17-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wirtz V, Cribb A, Barber N. Patient-doctor decision-making about treatment within the consultation--a critical analysis of models. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:116-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267:2221-2226. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Putniņa A. Bioethics and power: Informed consent procedures in post-socialist Latvia. Soc Sci Med. 2013;98:340-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Davies M, Elwyn G. Advocating mandatory patient 'autonomy' in healthcare: adverse reactions and side effects. Health Care Anal. 2008;16:315-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kukla R. Conscientious autonomy: displacing decisions in health care. Hastings Cent Rep. 2005;35:34-44. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Donchin, A. Autonomy and interdependence: Quandaries in genetic decision making. in relational autonomy: Feminist perspectives on autonomy, agency, and the social self. Mackenzie C, Stoljar N, editors. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000: 236-258. |

| 49. | Donchin A. Autonomy, interdependence, and assisted suicide: respecting boundaries/crossing lines. Bioethics. 2000;14:187-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Donchin A. Understanding autonomy relationally: toward a reconfiguration of bioethical principles. J Med Philos. 2001;26:365-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Foucault, M. Crisis de un modelo de medicina? Revista Centroamericana De Ciencias De La Salud. 1976;3:197-210. |

| 52. | Holmes D, Gastaldo D. Nursing as means of governmentality. J Adv Nurs. 2002;38:557-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Foucault, M. La incorporación del hospital en la tecnología moderna. Conferencia de 1974 en la universidad de Río de Janeiro [The incorporation of the hospital into modern technology. 1974 conference at the University of Rio de Janeiro]. Revista Centroamericana De Ciencias De La Salud. 1974;6:213-232. |

| 54. | Dzurec, L. Poststructuralist science: an historical account of profound visibility. In: Search of Nursing Science. Omery A, Kasper CE. y Page GG, editors. Newbry Park: Sage Publication, 1995: 233-244. |

| 55. | Foucault, M. El nacimiento de la medicina social. Conferencia del año 1974 en la universidad de Río de Janeiro [The birth of social medicine. Conference of the year 1974 at the University of Rio de Janeiro]. Revista Centroamericana De Ciencias De La Salud. 1977;6:167. |

| 56. | Foucault, M. ¿Crisis de un modelo de medicina? Revista Centroamericana De Ciencias De La Salud. 1976;3:177-211. |

| 57. | Castro Orellana, R. Ética para un rostro de arena: Michel Foucault y el cuidado de la libertad [Ethics for a face of sand: Michel Foucault and the care of freedom]. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2004. |

| 58. | Murray SJ, Holmes D. Critical interventions in the ethics of healthcare. Burlintong: Ashgate, 2009. |

| 59. | Fox NJ. Is there life after Foucault? In: Foucault. Health and medicine. Petersen A, Bunton R, editors. London: Routledge, 2000: 31-50. |

| 60. | Wolf S. Feminism and bioethics: Beyond reproduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. |

| 61. | Tong R. Feminist approaches to bioethics. In: Feminism and bioethics: Beyond reproduction. Wolf S, editor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996: 67-94. |

| 62. | Nicholson R. Limitations of the four principles. In: Principles of health care ethics. Gillon R, editor. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 1994: 267-275. |

| 63. | Bauman Z. Postmodern ethics. Oxford: Blackwell, 1993. |

| 64. | McGrath P. Autonomy, discourse, and power: a postmodern reflection on principlism and bioethics. J Med Philos. 1998;23:516-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Stevenson C. Theoretical and methodological approaches in discourse analysis. Nurse Researcher, 2004: 17 -29. |

| 66. | Jonsen A. The new medicine and the old ethics. London: Harvard University Press, 1990. |

| 67. | Foucault M. Vigilar y castigar: Nacimiento de la prisión. Madrid: Siglo XXI, 2004. |

| 68. | Dreyfus HL, Rabinow P. Michel Foucault. beyond structuralism and hermeneutics. United States of America: The University of Chicago Press, 1992. |

| 69. | Páez A. Ética y prácticas sociales. In: Abrahan T, Chibán E, Ferrer C, Maella G, Morello C, Páez A, Uhart H, Foucault y la ética. Buenos Aires: Docencia, 1998: 55-105. |

| 70. | Foucault M. Politics and ethics: An interview. The Foucault Reader. An Introduction to Foucault’s Thought, New York: Paidos, 1984. |

| 71. | Foucault M. Technologies of the self. In: Technologies of the self: A seminar with Michel Foucault. Martin LH, Gutman H, Hutton PHl, editors. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1988: 16-49. |

| 72. | Dingwall R, McIntosh J. Reading in sociology of nursing. Edinburg: Churchill Livingstone, 1978. |

| 73. | Iftode C. Foucault’s idea of philosophy as ‘Care of the Self:’ Critical assessment and conflicting metaphilosophical views. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013;71:76-85. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Podsakoff P, Schriesheim C. Field Studies of French and Raven’s Bases of Power: Critique, Reanalysis, and Suggestions for Future Research. Psychol Bull. 1985;97:387-411. |

| 75. | Laswell HD, Kaplan A. Power and Society, Yale: Yale University Press, 1950: 75. |

| 76. | Foucault M. Historia de la sexualidad. la voluntad del saber. 30th ed. Argentina: Siglo XXI, 2005. |

| 77. | Foucault M. The hermeneutics of the subject. Lectures at the college de France 1981-1982. New York: Picador, Palgrave Macmillan, 2005: 198-227. |

| 78. | Dorrestijn S. The Care of Our Hybrid Selves: Ethics in Times of Technical Mediation. Found Sci. 2017;22:311-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Abraham T. El último Foucault. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 2003. |

| 80. | Benhammou V, Warszawski J, Bellec S, Doz F, André N, Lacour B, Levine M, Bavoux F, Tubiana R, Mandelbrot L, Clavel J, Blanche S; ANRS-Enquête Périnatale Française. Incidence of cancer in children perinatally exposed to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. AIDS. 2008;22:2165-2177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Foucaul M. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College De France 1978-1979. New York: Picador, Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. |

| 82. | Bernauer B. Más allá de la vida y de la muerte. Foucault y la ética después de Auschwitz. In Foucault, M. Barcelona: Gedisa, 1995. |

| 83. | Huijer M. A Critical Use of Foucault's Art of Living. Found Sci. 2017;22:323-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Rojas Osorio C. Foucault y el pensamiento contemporáneo. Puerto Rico: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1995. |

| 85. | Perron A. Nursing as 'disobedient' practice: care of the nurse's self, parrhesia, and the dismantling of a baseless paradox. Nurs Philos. 2013;14:154-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Little M, Jordens C, Sayers E. Discourse communities and the discourse of experience. Health. 2003;7:73-86. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Gilbert TP. Trust and managerialism: exploring discourses of care. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:454-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Osborne T. Of health and statecraft. In: Foucault. Health and medicine. Petersen A, Bunton R, editors. London: Routledge, 1997: 37-64. |

| 89. | Beresford D. Clinical practice. family centred care: Fact or fiction? J Neonatal Nurs. 3:, 8-11. |

| 90. | Barbero C, Calv A, Gonzále G, Manrique R, Nespral C. Con lugar a dudas. Hilos y raíces del pensamiento crítico. Santander: Editorial límite, 2005. |

| 91. | Vahabi M, Gastaldo D. Rational choice(s)? Nurs Inq. 2003;10:245-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Manias E, Street A. Possibilities for critical social theory and Foucault's work: a toolbox approach. Nurs Inq. 2000;7:50-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Murillo S. El discurso de Foucault: Estado, locura y anormalidad en la construcción del individuo moderno. Buenos Aires: Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1996. |

| 94. | Molina Mula J. Saber, poder y cultura de sí en la construcción de la autonomía del paciente en la toma de decisiones. Relación de la enfermera con el paciente, familia, equipo de salud y sistema sanitario [Knowing, power and culture of oneself in the construction of the patient's autonomy in decision-making. Relationship of the nurse with the patient, family, health team and health system]. Palma de Mallorca: Universitat de les Illes Balears, 2013. |

| 95. | Foucault M. Colloqui con foucault. Conversación Con Duccio Trombadori. Nueva York: Salerno, 1981. |