Published online Sep 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i25.7472

Peer-review started: April 18, 2021

First decision: May 24, 2021

Revised: May 26, 2021

Accepted: July 14, 2021

Article in press: July 14, 2021

Published online: September 6, 2021

Processing time: 134 Days and 13.9 Hours

Laminopathies are rare diseases, whose cardiac manifestations are heterogeneous and, especially in their initial stage, similar to those of more common conditions, such as ischemic heart disease. Early diagnosis is essential, as these conditions can first manifest themselves with sudden cardiac death. Electrical complications usually appear before structural complications; therefore, it is important to take into consideration these rare genetic disorders for the differential diagnosis of brady and tachyarrhythmias, even when left ventricle systolic function is still preserved.

A 60-year-old man, without history of previous disorders, presented in September 2019 to the emergency department because of the onset of syncope associated with hypotension. The patient was diagnosed with a high-grade atrioventricular block. A dual chamber pacemaker was implanted, but after the onset of a sus

This case aims to raise awareness of the cardiological manifestations of laminopathies, which can be dangerously misdiagnosed as other, more common con

Core Tip: Cardiolaminopathy diagnosis, especially in its initial stage, is challenging. In presence of misleading factors, such as coronary stenosis, and limiting factors, such as the coronavirus disease 2019-related lockdown, the difficulties increase. Remote monitoring for assessing arrhythmic burden and clinical suspicion make it possible to safely diagnose this rare disease.

- Citation: Santobuono VE, Guaricci AI, Carulli E, Bozza N, Pepe M, Ranauro A, Ranieri C, Carella MC, Loizzi F, Resta N, Favale S, Forleo C. Importance of clinical suspicion and multidisciplinary management for early diagnosis of a cardiac laminopathy patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(25): 7472-7477

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i25/7472.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i25.7472

The lamin A/C (LMNA) gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 1 (1q22), codes Lamins A and C by means of alternative splicing. These two intermediate filament proteins belong to the nuclear lamina that underlies and supports the nuclear membrane of eukaryotic cells. LMNA gene mutations have been shown to cause several pathological conditions (generally known as laminopathies), such as lipodystrophies, restrictive dermopathies, premature ageing syndromes, peripheral neuropathies, and different types of muscular dystrophy[1]. LMNA defects have the worst repercussions on specific tissues, such as neuronal, adipose, epithelial, and striated muscular tissues. With regard to the latter, the possible involvement of the myocardium deserves special mention, as this can lead to cardiac phenotypes characterized by the coexistence of both electrical and mechanical manifestations. Electrical manifestations, which usually appear before mechanical ones, by several years, consist of atrio- and intraventricular conduction abnormalities and atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias that can cause sudden cardiac death. On the other hand, cardio

Our patient was a 60-year-old Caucasian male who presented in September 2019 with syncope associated with hypotension.

The patient had no previous symptoms and syncope was indeed the first clinical manifestation.

The patient had no history of previous disease and he was not taking any medications.

The only red flags were the known congenital bicuspid aortic valve and family history of congestive heart failure (sister).

When he came to the emergency department, he presented hypotensive, with tachyarrhythmic peripheral pulse. A paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) episode was diagnosed, which regressed after a few hours.

Routine laboratory tests (complete blood count, kidney function, electrolytes, liver and heart enzymes) were all in the normal ranges.

Transthoracic echocardiography showed no pathological findings.

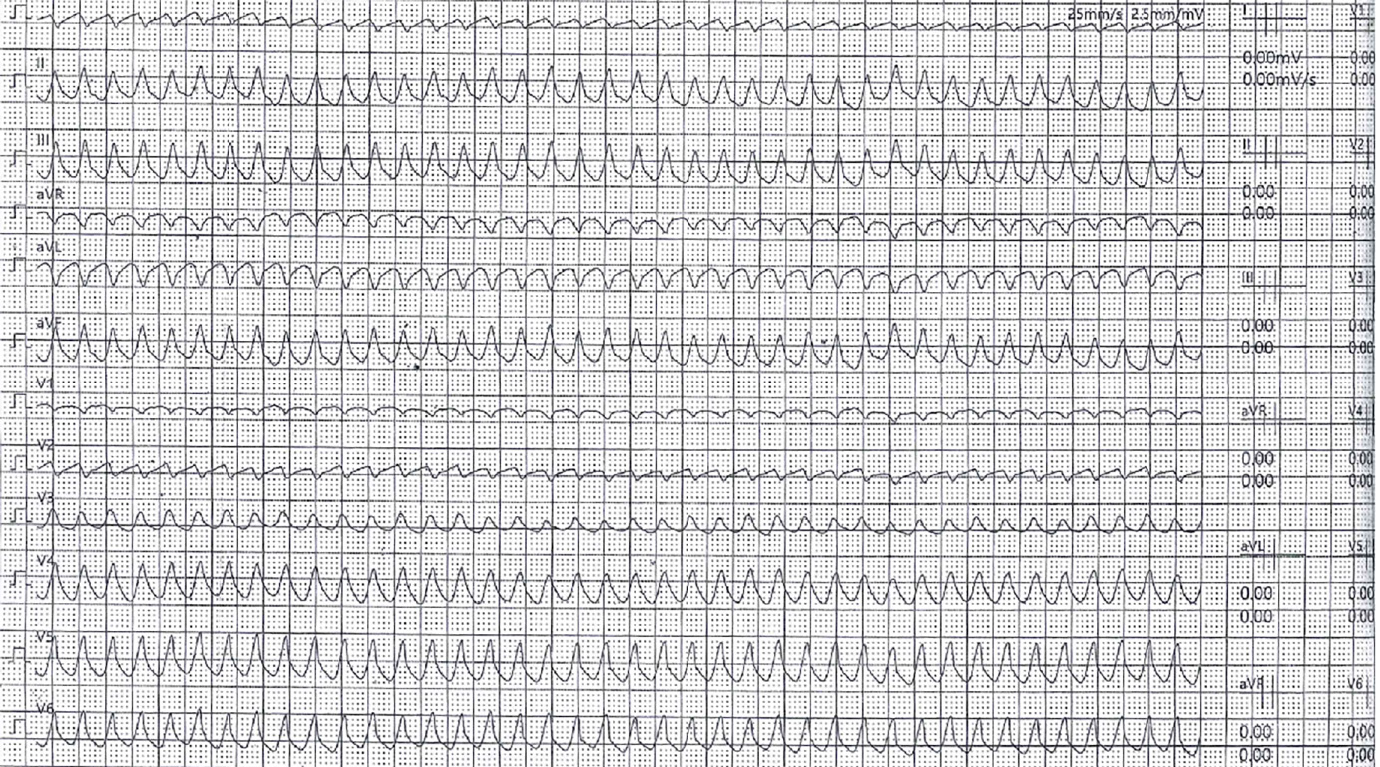

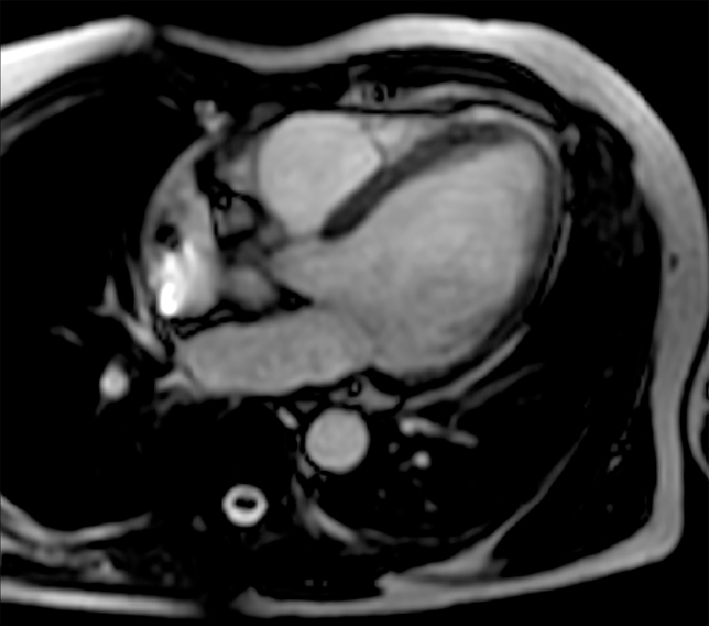

The 24-h electrocardiogram Holter monitoring recorded frequent episodes of high-grade atrioventricular block with no further AF episodes. Upon suspicion of an ischemic aetiology, he was admitted to the cardiology unit and underwent coronarography, which indicated intermediate stenosis (50%) in the left anterior descending artery. This stenosis was not considered hemodynamically significant. Thus, the decision was to implant a dual chamber anti-bradycardia pacemaker. Given the single and short AF episode and the CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0, no anticoagulation treatment was initiated. In December 2019, he underwent a scintigraphy stress–rest test, during which he presented loss of consciousness due to the onset of sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) (Figure 1), which was successfully treated with cardiopulmonary resuscitation manoeuvres and lidocaine infusion. The arrhythmia was considered to be of ischaemic origin. Therefore, the patient underwent percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty with drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation at the known coronary stenosis. During and after hospitalization, numerous non-sustained VTs were recorded, for which he was given amiodarone, with clinical benefit. After a few weeks, a treadmill stress test was also performed under antiarrhythmic therapy, which was negative for both myocardial ischemia and VTs. During the follow-up examinations, considering the patient’s clinical picture, encompassing VT, atrioventricular block, family history, and echocardiographic findings showing accentuated right ventricular apex trabeculation, the treating cardiologist decided to reassess the clinical case. He recommended that the patient undergo cardiac magnetic resonance and molecular analysis performed with a panel of 128 genes known to be associated with cardiomyopathies and channelopathies. Both tests were performed in February 2020 (6 wk after DES implantation, as indicated in the manufacturer’s data sheet). The former showed a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 50% without any areas of late enhancement or myocardial fibrosis (Figure 2).

The results of the genetic testing took 3 mo to be validated, during which outpatient appointments with patients were suddenly stopped due to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-related pandemic. Considering the need to supervise the patient during this time for the possible onset of life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmia (LTVT) and AF, without the possibility of a periodic in person interrogation of the PM arrhythmias registry, as was usually done, it was decided to give the patient a remote monitoring device (Medtronic Carelink Network®). The device was configurated to transmit the data it recorded, automatically every week. At the same time, both LTVT and AF were set up as “care alerts”, which meant that an automatic alert would have been sent immediately after identification, , as long as the potential LTVT or AF onset would have required a prompt and potentially lifesaving intervention, either the upgrading the PM to an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) or the initiation of a life-long anticoagulant therapy, respectively. Fortunately, no arrhyth

The genetic test reported a heterozygous missense mutation (c.949G>A; p.Glu317Lys) in exon 6 of the LMNA gene, which is known to be a pathogenic variant. A further LVEF reduction of 43% was observed. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with cardiac manifestation of laminopathy.

Based on the new diagnosis, it was decided to hospitalize the patient to upgrade the PM to a biventricular ICD.

The patient is currently asymptomatic for heart failure. No further LTVT has occurred. He is still using the remote monitoring device in order to promptly identify any new AF episode that would potentially require life-long anticoagulant therapy. The patient is continuing follow-up with both clinical and echocardiographic re-evaluation associated with an electronic check of the ICD.

The decision to protect the patient from LTVT was made in accordance with current guidelines[3,4], which recommend device implantation (class of recommendation IIa) in patients with LMNA gene mutations in the presence of at least two of the following risk factors: (1) Non-sustained VT; (2) LVEF < 45%; (3) Male sex; and (4) Non-missense mutations. However, Wahbi et al[5] recently proposed a new risk score that also takes into account the history of atrioventricular block. The latter has been shown to have a greater accuracy in the risk prediction of LTVT, which for our patient was 41.6%. Based on the 2016 heart failure ESC guidelines[6] (class of recommendation I), we opted for a biventricular ICD in light of the high percentage of pacing (99.4%) and of the concomitant rapid reduction in left ventricular systolic function after PM implantation (LVEF from 60% in December 2019 to 50% in February 2020 to 43% in June 2020), which could also be explained by the more aggressive clinical course of LMNA-related DCM compared with other forms[7].

Laminopathies have a heterogeneous spectrum of cardiological manifestations ranging from supraventricular and ventricular tachyarrhythmias to atrio- and intraventricular conduction disorders and left ventricular dysfunction[1,8]. Moreover, clinical manifestations of cardiac phenotypes tend to occur in an age-related way, starting in the fourth decade of life and reaching 90%-95% of subjects by the seventh decade[1,8], which corresponds to the timing of the presentation of coronary atherosclerotic disease and idiopathic senile degeneration of cardiac conduction tissue. However, since the latter aetiologias are considerably more frequent than the genetic ones, it is easy to attribute cardiological disorders to them. This was applicable to our patient, in whom the electrical laminopathy manifestations were erroneously confused with manifestations of coronary disease. This belief was supported by the incidental finding of an intermediate lesion on coronarography, which led the treating physician to implant a probably unnecessary DES and consequently start dual antiplatelet therapy, a treatment that brings an obvious increase in the ischaemic and haemorrhagic risks. The choice to carry out genetic testing in our patient was mainly driven by the overall clinical picture, although it did not fully respect the indications of the Heart Rhythm Society/European Heart Rhythm Association consensus statement[9], which instead recommends genetic testing in patients with atrioventricular block and DCM. In fact, at the time of genetic testing, echocardiography did not yet show signs of chamber dilation. The initial presentation with electrical complications in structurally healthy hearts is quite common since the structural cardiac manifestations usually arise after the electrical ones[10]. However, in LMNA-related DCM patients, who are at high arrhythmic risk, delaying the diagnosis and waiting for the onset of late mechanical manifestations, in order to follow the guidelines for genetic testing, can also lead to delayed treatment and defibrillator implantation, with possible fatal consequences.

Our case testifies to several findings: (1) How difficult it is to diagnose cardio

The authors are grateful to the patient for allowing publication of this rare case report.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Feng R, Leslie SJ S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor:Ma YJ

| 1. | Peretto G, Di Resta C, Perversi J, Forleo C, Maggi L, Politano L, Barison A, Previtali SC, Carboni N, Brun F, Pegoraro E, D'Amico A, Rodolico C, Magri F, Manzi RC, Palladino A, Isola F, Gigli L, Mongini TE, Semplicini C, Calore C, Ricci G, Comi GP, Ruggiero L, Bertini E, Bonomo P, Nigro G, Resta N, Emdin M, Favale S, Siciliano G, Santoro L, Sinagra G, Limongelli G, Ambrosi A, Ferrari M, Golzio PG, Bella PD, Benedetti S, Sala S; Italian Network for Laminopathies (NIL). Cardiac and Neuromuscular Features of Patients With LMNA-Related Cardiomyopathy. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:458-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Peretto G, Sala S, Benedetti S, Di Resta C, Gigli L, Ferrari M, Della Bella P. Updated clinical overview on cardiac laminopathies: an electrical and mechanical disease. Nucleus. 2018;9:380-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen K, Kuck KH, Hernandez-Madrid A, Nikolaou N, Norekvål TM, Spaulding C, Van Veldhuisen DJ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: the task force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the european society of cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: association for european paediatric and congenital cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2793-2867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2447] [Cited by in RCA: 2645] [Article Influence: 264.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, Deal BJ, Dickfeld T, Field ME, Fonarow GC, Gillis AM, Granger CB, Hammill SC, Hlatky MA, Joglar JA, Kay GN, Matlock DD, Myerburg RJ, Page RL. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:e91-e220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 809] [Article Influence: 115.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wahbi K, Ben Yaou R, Gandjbakhch E, Anselme F, Gossios T, Lakdawala NK, Stalens C, Sacher F, Babuty D, Trochu JN, Moubarak G, Savvatis K, Porcher R, Laforêt P, Fayssoil A, Marijon E, Stojkovic T, Béhin A, Leonard-Louis S, Sole G, Labombarda F, Richard P, Metay C, Quijano-Roy S, Dabaj I, Klug D, Vantyghem MC, Chevalier P, Ambrosi P, Salort E, Sadoul N, Waintraub X, Chikhaoui K, Mabo P, Combes N, Maury P, Sellal JM, Tedrow UB, Kalman JM, Vohra J, Androulakis AFA, Zeppenfeld K, Thompson T, Barnerias C, Bécane HM, Bieth E, Boccara F, Bonnet D, Bouhour F, Boulé S, Brehin AC, Chapon F, Cintas P, Cuisset JM, Davy JM, De Sandre-Giovannoli A, Demurger F, Desguerre I, Dieterich K, Durigneux J, Echaniz-Laguna A, Eschalier R, Ferreiro A, Ferrer X, Francannet C, Fradin M, Gaborit B, Gay A, Hagège A, Isapof A, Jeru I, Juntas Morales R, Lagrue E, Lamblin N, Lascols O, Laugel V, Lazarus A, Leturcq F, Levy N, Magot A, Manel V, Martins R, Mayer M, Mercier S, Meune C, Michaud M, Minot-Myhié MC, Muchir A, Nadaj-Pakleza A, Péréon Y, Petiot P, Petit F, Praline J, Rollin A, Sabouraud P, Sarret C, Schaeffer S, Taithe F, Tard C, Tiffreau V, Toutain A, Vatier C, Walther-Louvier U, Eymard B, Charron P, Vigouroux C, Bonne G, Kumar S, Elliott P, Duboc D. Development and validation of a new risk prediction score for life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias in laminopathies. Circulation. 2019;140:293-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; Authors/Task Force Members; Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4368] [Cited by in RCA: 4909] [Article Influence: 545.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 7. | Charron P, Arbustini E, Bonne G. What Should the Cardiologist know about Lamin Disease? Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2012;1:22-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fatkin D, MacRae C, Sasaki T, Wolff MR, Porcu M, Frenneaux M, Atherton J, Vidaillet HJ Jr, Spudich S, De Girolami U, Seidman JG, Seidman C, Muntoni F, Müehle G, Johnson W, McDonough B. Missense mutations in the rod domain of the lamin A/C gene as causes of dilated cardiomyopathy and conduction-system disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1715-1724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 945] [Cited by in RCA: 934] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ackerman MJ, Priori SG, Willems S, Berul C, Brugada R, Calkins H, Camm AJ, Ellinor PT, Gollob M, Hamilton R, Hershberger RE, Judge DP, Le Marec H, McKenna WJ, Schulze-Bahr E, Semsarian C, Towbin JA, Watkins H, Wilde A, Wolpert C, Zipes DP. HRS/EHRA expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for the channelopathies and cardiomyopathies this document was developed as a partnership between the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1308-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 760] [Article Influence: 58.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kumar S, Baldinger SH, Gandjbakhch E, Maury P, Sellal JM, Androulakis AF, Waintraub X, Charron P, Rollin A, Richard P, Stevenson WG, Macintyre CJ, Ho CY, Thompson T, Vohra JK, Kalman JM, Zeppenfeld K, Sacher F, Tedrow UB, Lakdawala NK. Long-term arrhythmic and nonarrhythmic outcomes of Lamin A/C mutation carriers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2299-2307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |