Published online Sep 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i25.7459

Peer-review started: December 16, 2020

First decision: June 4, 2021

Revised: July 8, 2021

Accepted: July 19, 2021

Article in press: July 19, 2021

Published online: September 6, 2021

Processing time: 257 Days and 19.3 Hours

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare mucinous neoplasm with a relatively low incidence of 1 to 2 per million individuals. It is typically characterized by a type of gelatinous ascites named “jelly belly”. Most cases of PMP occur in association with ruptured primary mucinous tumors of the appendix (90%). Periodically, PMP can originate from mucinous carcinomas at other sites, including the colorectum, gallbladder, and pancreas. However, unusual origin can occur, as noted in this case report.

A 52-year-old woman had an unusual derivation of PMP from intestinal duplication. The patient complained of abdominal distension and increasing abdominal girth. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed a mass in the greater omentum located on the left side of the abdomen, likely to be a cystic mass of peritoneal origin. A PMP diagnosis was presumed based on the specific signs of the mass with flocculent and stripe-like echoes in ultrasound images. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous aspiration suggested a high likelihood of PMP. Once the PMP diagnosis was recognized, identification of the origin of the primary tumor was indicated. Thus, an exploratory laparoscopy was performed. In the absence of a primary tumor of appendix origin, the diagnosis of a low-grade mucinous neoplasm of intestinal duplication origin was finally confirmed by histopathology.

PMP is secondary to mucinous carcinomas of the appendix mostly. This case resulted from an unusual derivation from intestinal duplication.

Core Tip: Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) happens rarely. Most of the tumors that occur in PMP are not primary, but secondary to ruptured mucinous tumors of other organs. Existent medical literature shows that the appendix is the most common origin site. However, other origins such as intestinal duplication can occur. The present case report describes a 52-year-old patient with PMP that is derived from a primary intestinal duplication.

- Citation: Han XD, Zhou N, Lu YY, Xu HB, Guo J, Liang L. Pseudomyxoma peritonei originating from intestinal duplication: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(25): 7459-7467

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i25/7459.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i25.7459

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is an uncommon disease with a relatively low incidence of 1 to 2 per million individuals[1,2]. PMP is often misdiagnosed clinically due to the lack of specific clinical presentation[3].

Classically, most PMP tumors are not primary, but secondary to ruptured mucinous tumors of other organs, especially the appendix[4]. Occasionally, PMP arises from adenocarcinomas of other sites within the gastrointestinal tract[5,6]. Typically, this disorder is characterized by an abundant accumulation of mucinous ascites developing from mucin secretion by a primary tumour[7-9]. The primary tumour ruptures and tumor cells then spread to implant throughout the peritoneal cavity, which results in the typical “jelly belly” appearance. Considering the rarity of the primary lesion of intestinal duplication, we report the current case with PMP seen in our hospital. This is an extremely rare origin of tumor disease.

A 52-year-old woman presented with the symptoms of abdominal distension and increasing abdominal girth.

Because of decreased appetite, the patient was referred to our hospital for further evaluation.

The patient had a rheumatoid arthritis history for 18 years. She also had a diagnosis of superficial gastritis for 2 mo.

There was no family history.

Physical examination revealed the patient had a distended abdomen with a hard and non-tender mass. The mass was approximately 15 cm in diameters with ill-defined margins. Shifting dullness could not be found.

Blood examination was performed. Normal levels of the tumor markers carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 12-5 (CA12-5), CA19-9, and CA724 were observed. However, an increased CA242 level (25.87 U/mL) was found. Other physical examination results were as follows: Body temperature 37.0 degrees, pulse 80 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, blood pressure 120/70 mmHg, and abdominal gurgling sounds approximately three times per minute. No abnormalities were seen on the ultrasonic cardiogram or gastroscopy. The patient had a relatively unremarkable previous medical history apart from rheumatoid arthritis. She denied any other relevant, specific past medical or family medical history. The urinary and bowel elimination functions were reported to be good. She denied weight loss.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CECT) (Figure 1) showed a mass in the greater omentum located on the left side of the abdomen, likely to be a cystic mass of peritoneal origin.

Ultrasound indicated that the mass in the left upper and middle abdomen was flocculent, with an internal stripe-like echo (Figure 2A). The mass could not be deformed by the probe pressing technique[10,11]. The space occupying lesion looked like a mucinous mass, on the basis of the flocculent and stripe-like echoes observed in the scan. Subsequently, ultrasound-guided percutaneous aspiration of the cystic lesion revealed hallmark yellow gelatinous material characteristic (Figure 2B). These findings, combined with the clinical presentation, suggested a clinical diagnosis of PMP.

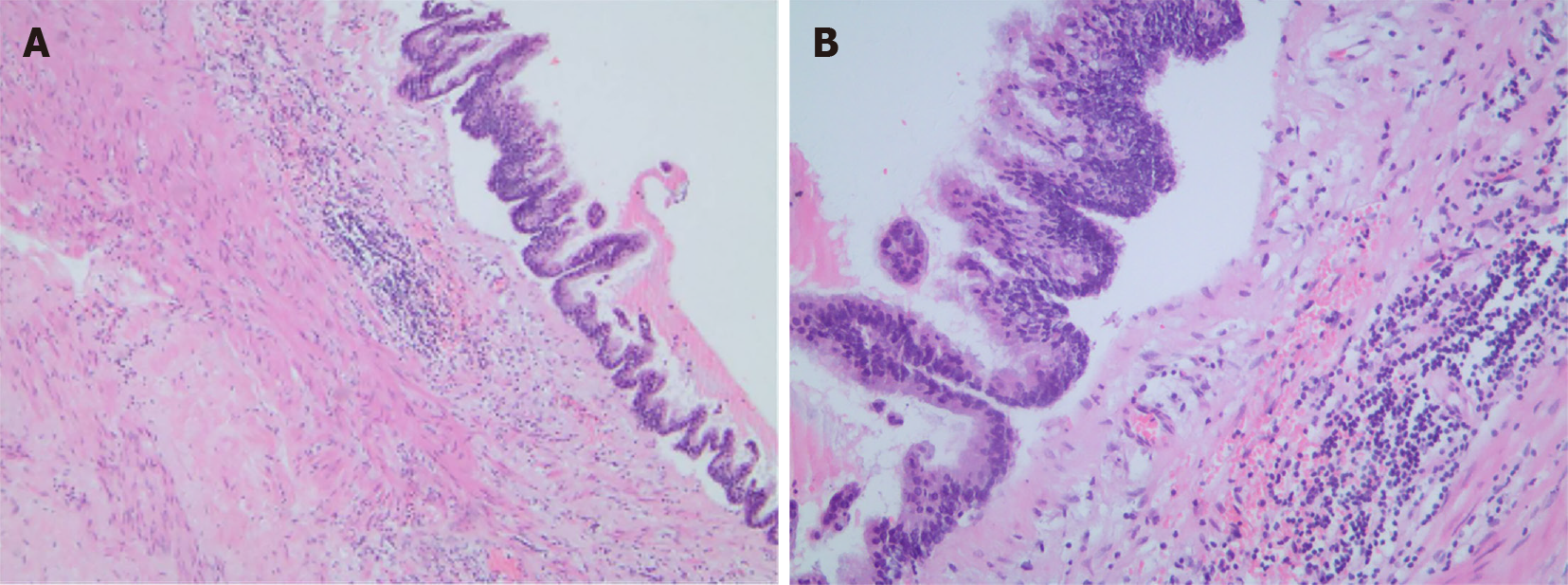

Once the PMP diagnosis was recognized, identification of the origin was indicated. Thus, an exploratory laparoscopy was performed. It showed a mass with cystic characteristics and jelly-like content located inside the greater omental cavity. Considering the jelly in the greater omentum, the suspicion of PMP increased in possibility[12]. However, from macroscopic observation, the appendix had an elongated shape with no edema or tumor mass. Nonetheless, complete microscopic tissue examination of the appendix was needed. Considering that appendiceal origin was most likely, appendectomy was performed with the permission of the family. Frozen sections of the excised appendiceal tissue were immediately analyzed during the operation. Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining showed chronic appendicitis obliterans of the tissue (Figure 3).

Women with PMP often have mucinous tumors involving both the appendix and the ovary[13,14]. Hence, the ovaries were carefully inspected in the patient, which showed negative results. Exploratory laparotomy therefore continued, in the absence of primary tumors from appendix and ovary. The location of jelly in the omental cavity necessitated total omentum removal. During radical greater omentectomy, an extremely sticky mucoid material was observed proximal to the splenic flexure of colon, which was a helpful feature likely signaling the primary origin of the cystic tumor. Besides, it was consistent with the location of the lesion on preoperative CECT imaging. Therefore, the sticky mucoid material was separated. And a mucinous tumor was found located on the anterior lobe of mesocolon on the left part of the splenic flexure of the transverse colon (Figure 4). Omentectomy was performed as the preferred option under this set of conditions.

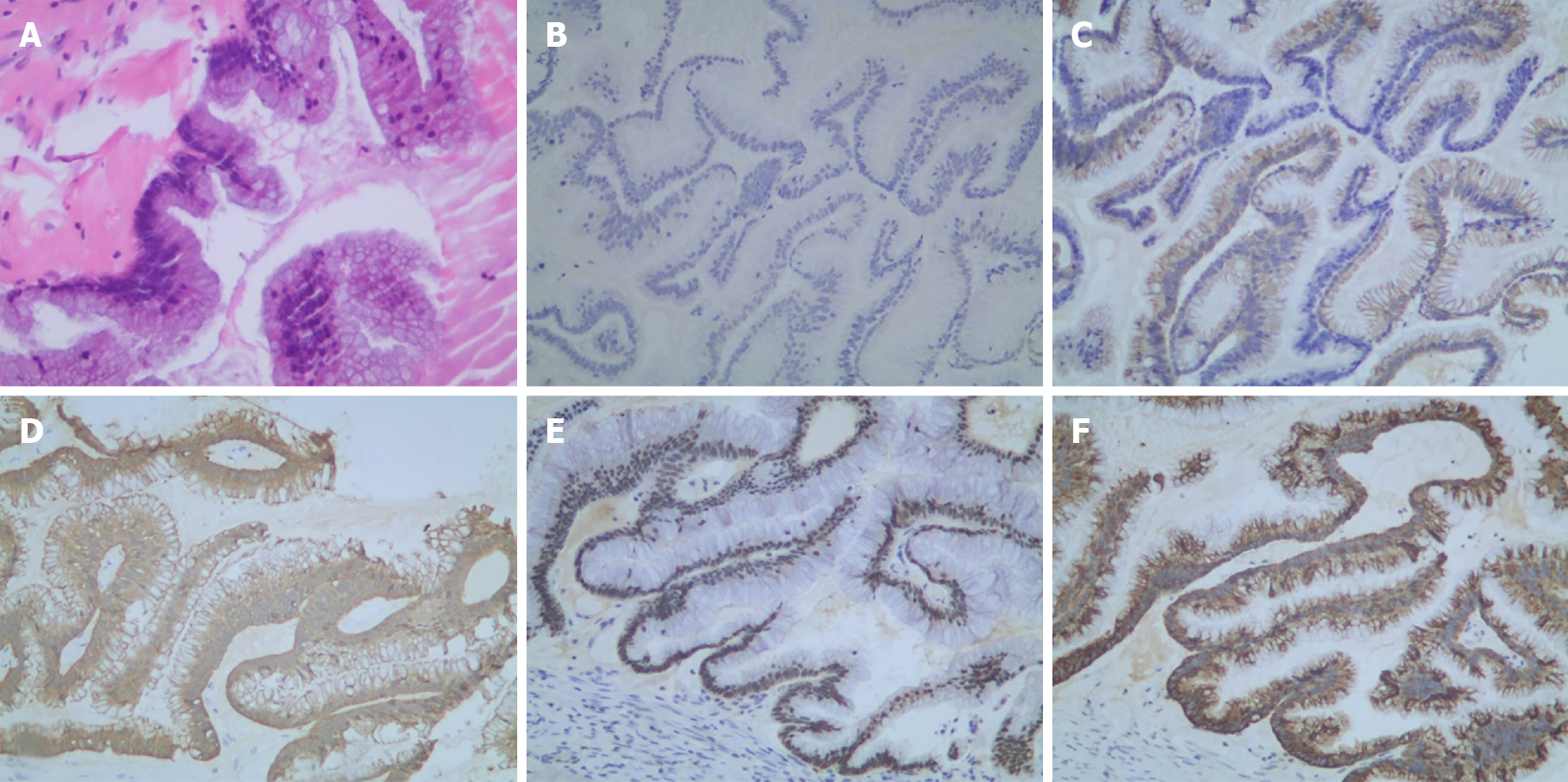

There was a subsequent finding of mucoid material in the anterior lobe of the transverse mesocolon. Immunohistochemistry identified intestinal duplication origin. Low-grade mucinous epithelial cells were lining in the capsule wall of the cystic mass in the focal area. Extensive fibrosis and calcifications were found in the cystic wall. The smooth muscle layer could also be seen at some sites (Figure 5).

As shown in Figure 6, immunohistochemical staining of the mucinous tumor lesion demonstrated negative expression of cytokeratin (CK)-7, but strongly positive expression of CK-20, Villin, CDX-2, and Mucin 2 (MUC-2). PMP typically originates from MUC-2 over-expression of goblet cells[15]. CDX-2 plays a crucial role in cell proliferation and differentiation[16]. The finding of CDX-2 positive expression indicated that the tumor originated from the gastrointestinal (alimentary) system[17].

Further pathology consultation with two other hospitals (Peking University Cancer Hospital and Peking Union Medical College Hospital) was performed to confirm the diagnosis. The two hospitals obtained the similar results that the presented case was PMP derived from intestinal duplication.

Macroscopic tumor excision combined with heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has shown encouraging outcomes for extra-appendiceal PMP[2,18]. The patient was therefore treated with HIPEC, which consisted of 10 mg of mitomycin and 40 mg of cisplatin along with concurrent intravenous chemotherapy therapy of 5-FU (1 g). A 90-min thermal cycle was adopted.

The peritoneal cancer index[19] was estimated in the patient to assess the extent of PMP. The size of the lesion was scored: 0 = no tumor, 1 = tumor ≤ 0.5 cm, 2 = 0.5 cm < tumor ≤ 5.0 cm, and 3 = tumor > 5.0 cm. The cystic lesion was located behind the posterior wall of stomach, in the front of the pancreas, and on the inside of the spleen, which occupied regions of 3, 4, and 0. The scores of the three regions were all 3. The jelly like ascites in the uterus-rectum-fossa in region 6 was scored 1. Thus, the aggregative score of 13 abdominopelvic regions reached 10 in surgery. A complete cytoreduction was achieved after surgery. The degree of cytoreduction reached a grade of 0. Post-treatment CEA, CA12-5, CA19-9, CA724, and CA242 were all negative. Additionally, no obvious abnormalities were observed on repeat abdominal computed tomography (CT). The patient had no tumor recurrence in follow-up visits until May, 2020 (5 years after the initial operation).

The diagnosis of PMP, a rare clinical syndrome, is difficult[20,21]. Commonly, the presenting symptom is increasing abdominal girth. As symptoms are typically non-specific, an initial misdiagnosis of other conditions occurs frequently. Usually a suspected diagnosis may be made by ultrasonography. Ultrasonography, CT, and other examinations, followed by histopathologic verification of extensively sampled tumor, are the preferred ways to confirm a diagnosis of PMP[22]. The feature of flocculent and stripe-like echoes could be detected by an experienced observer[10,23], which is helpful for the diagnosis of PMP. Detection of yellow gelatinous material[24] via transabdominal ultrasound-guided percutaneous aspiration strengthens the probability of PMP diagnosis.

Once the PMP diagnosis is recognized, the source should be identified. The great majority of PMP cases are associated with the spread of a primary mucin-producing tumor of the appendix, accounting for approximately 90% of cases. According to the clinical experience of our center, more than 86% (904/1050) of the center’s PMP cases originated from appendix. A primary PMP tumor can arise from elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract as well. Since most PMP cases are due to appendiceal tumors, the appendiceal region should be closely inspected. Studies[25,26] have reported that it might be impossible to identify an appendiceal origin of PMP at surgery because the residual appendix may be small or fibrosed after rupture. Thus, it is preferred to perform an appendectomy. The appendix should be sent for serial sections for definitive histopathology examination before another primary site is considered[27]. The coexistence of ovarian and appendiceal mucinous tumors is commonly encountered[4]. Substantial research discusses long-held controversies regarding origin from either the appendix or the ovary in mucinous tumor cases of PMP in women. Several studies[28-31] have suggested that most cases of PMP in women are of intestinal origin with secondary ovarian involvement. The removal of the ovaries is routinely advised in patients with colonic origin of carcinomatosis and menopause, as there is a high chance of ovarian metastasis.

Since there was an abnormal omental mass indicated by preoperative CT in this case, careful inspection of the anatomic region of the peritoneal cavity where extremely sticky mucoid material occurred was required. Finally, a mucinous tumor in the anterior lobe of the transverse mesocolon was observed on exploratory laparoscopy, though peritoneal tumors were difficult to identify. The subsequent pathology test of the lesion revealed a low-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma, originating from intestinal duplication.

In terms of severity of the disease, PMP is classified into either low-grade or high-grade mucious adenocarcinomas. The distinction between low-grade and high-grade carcinomas is of prognostic significance. Patients with low-grade tumors generally have a good 5-year survival of 63%-86% comparatively, whereas high-grade tumors generally indicate a survival of only 28%-44%[2,30,31]. It is noteworthy that adult intestinal duplication is quite rare[32]. In the current case, the intestinal duplication was characterized by well-developed smooth muscle. Additionally, a low-grade mucinous epithelium and smooth muscular layers in the intestinal tumor focal area were present. Typically, intestinal duplication arises from the mesenteric border of the bowel[33]. But the abnormal changes in the mesentery or mesocolon could not be detected by ultrasound or CT due to the anatomical complexity of the region[34].

It is hypothesized that the case was caused by the metaplasia of mucous epithelial cells in duplication of the intestine. Mucinous tumor cells produced progressive amounts of mucinous materials and then penetrated through the intestinal wall, eventually spread to the peritoneal cavity in the form of gelatinous deposits. Increased abdominal girth then occurred, but the mechanism for this process needed further study. PMP tumors are mostly CK-20 positive and CK-7 negative. The positive expression of CDX-2 in this case indicated an origin from the gastrointestinal system[33-37]. High level of CA242 was also effective in diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancer[38].

In conclusion, PMP is a rare condition characterized by the deposition of mucinous material on peritoneal surfaces. Most of the tumors are not primary, but secondary to ruptured mucinous tumors of other organs[5]. The appendix is by far the most common primary site. It is noteworthy that intestinal duplication could also be the origin of PMP, which was also reported by Lemahieu et al[39] and Letarte et al[40].

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Morera-Ocon FJ, Morris DL S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Smeenk RM, van Velthuysen ML, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Appendiceal neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei: a population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:196-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Mittal R, Chandramohan A, Moran B. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: natural history and treatment. Int J Hyperthermia. 2017;33:511-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Järvinen P, Lepistö A. Clinical presentation of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Scand J Surg. 2010;99:213-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Guo AT, Song X, Wei LX, Zhao P. Histological origin of pseudomyxoma peritonei in Chinese women: clinicopathology and immunohistochemistry. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3531-3537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Simons M, Ebisch I, de Hullu J, van Ham M, Snijders M, de Kievit I, Bulten J. A Patient With a Low-grade Mucinous Neoplasm Involving the Ovary and Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Originating in an Isolated Intestinal Duplication. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2018;37:338-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chauhan A, Patodi N, Ahmed M. A rare cause of ascites: pseudomyxoma peritonei and a review of the literature. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:156-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bevan KE, Mohamed F, Moran BJ. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:44-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gupta S, Singh G, Gupta A, Singh H, Arya AK, Shrotriya D, Kumar A. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: An uncommon tumor. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2010;31:58-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Amini A, Masoumi-Moghaddam S, Ehteda A, Morris DL. Secreted mucins in pseudomyxoma peritonei: pathophysiological significance and potential therapeutic prospects. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Que Y, Tao C, Wang X, Zhang Y, Chen B. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: some different sonographic findings. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37:843-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Appelman Z, Zbar AP, Hazan Y, Ben-Arie A, Caspi B. Mucin stratification in pseudomyxoma peritonei: a pathognomonic ultrasonographic sign. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:96-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moran BJ, Cecil TD. The etiology, clinical presentation, and management of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12:585-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chuaqui RF, Zhuang Z, Emmert-Buck MR, Bryant BR, Nogales F, Tavassoli FA, Merino MJ. Genetic analysis of synchronous mucinous tumors of the ovary and appendix. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Suh DS, Song YJ, Kwon BS, Lee S, Lee NK, Choi KU, Kim KH. An unusual case of pseudomyxoma peritonei associated with synchronous primary mucinous tumors of the ovary and appendix: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4813-4817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | O'Connell JT, Tomlinson JS, Roberts AA, McGonigle KF, Barsky SH. Pseudomyxoma peritonei is a disease of MUC2-expressing goblet cells. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:551-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, Gown AM. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 539] [Cited by in RCA: 502] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Smeenk RM, Bruin SC, van Velthuysen ML, Verwaal VJ. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. Curr Probl Surg. 2008;45:527-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rizvi SA, Syed W, Shergill R. Approach to pseudomyxoma peritonei. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;10:49-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Llueca A, Escrig J; MUAPOS working group (Multidisciplinary Unit of Abdominal Pelvic Oncology Surgery). Prognostic value of peritoneal cancer index in primary advanced ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mavrodin C, Pariza G, Iordache V, Iorga P, Sajin M. Pseudomixoma peritonei, a rare entity difficult to diagnose and treat - case report. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2014;109:846-849. [PubMed] |

| 21. | de Oliveira AM, Rodrigues CG, Borges A, Martins A, Dos Santos SL, Rocha Pires F, Mascarenhas Araújo J, Ramos de Deus J. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: a clinical case of this poorly understood condition. Int J Gen Med. 2014;7:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sugiyama K, Ito N. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the urachus associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei with emphasis on MR findings. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2009;8:85-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chira RI, Nistor-Ciurba CC, Mociran A, Mircea PA. Appendicular mucinous adenocarcinoma associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei, a rare and difficult imaging diagnosis. Med Ultrason. 2016;18:257-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Badyal RK, Khairwa A, Rajwanshi A, Nijhawan R, Radhika S, Gupta N, Dey P. Significance of epithelial cell clusters in pseudomyxoma peritonei. Cytopathology. 2016;27:418-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sugarbaker PH, Ronnett BM, Archer A, Averbach AM, Bland R, Chang D, Dalton RR, Ettinghausen SE, Jacquet P, Jelinek J, Koslowe P, Kurman RJ, Shmookler B, Stephens AD, Steves MA, Stuart OA, White S, Zahn CM, Zoetmulder FA. Pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome. Adv Surg. 1996;30:233-280. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Buell-Gutbrod R, Gwin K. Pathologic diagnosis, origin, and natural history of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013;221-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yan F, Shi F, Li X, Yu C, Lin Y, Li Y, Jin M. Clinicopathological Characteristics of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Originated from Ovaries. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:7569-7578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hart WR. Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005;24:4-25. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Morera-Ocon FJ, Navarro-Campoy C. History of pseudomyxoma peritonei from its origin to the first decades of the twenty-first century. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;11:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Moran B, Baratti D, Yan TD, Kusamura S, Deraco M. Consensus statement on the loco-regional treatment of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms with peritoneal dissemination (pseudomyxoma peritonei). J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:277-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Panarelli NC, Yantiss RK. Mucinous neoplasms of the appendix and peritoneum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:1261-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Blickman JG, Rieu PH, Buonomo C, Hoogeveen YL, Boetes C. Colonic duplications: clinical presentation and radiologic features of five cases. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:14-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Martini C, Pagano P, Perrone G, Bresciani P, Dell'Abate P. Intestinal duplications: incidentally ileum duplication cyst in young female. BJR Case Rep. 2019;5:20180077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Huang ZH, Wan ZH, Vikash V, Vikash S, Jiang CQ. Report of a rare case and review of adult intestinal duplication at the opposite side of mesenteric margin. Sao Paulo Med J. 2018;136:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Fallis SA, Moran BJ. Management of pseudomyxoma peritonei. J BUON. 2015;20 Suppl 1:S47-S55. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Baratti D, Kusamura S, Milione M, Pietrantonio F, Caporale M, Guaglio M, Deraco M. Pseudomyxoma Peritonei of Extra-Appendiceal Origin: A Comparative Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:4222-4230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nonaka D, Kusamura S, Baratti D, Casali P, Younan R, Deraco M. CDX-2 expression in pseudomyxoma peritonei: a clinicopathological study of 42 cases. Histopathology. 2006;49:381-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nilsson O, Johansson C, Glimelius B, Persson B, Nørgaard-Pedersen B, Andrén-Sandberg A, Lindholm L. Sensitivity and specificity of CA242 in gastro-intestinal cancer. A comparison with CEA, CA50 and CA 19-9. Br J Cancer. 1992;65:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lemahieu J, D'Hoore A, Deloose S, Sciot R, Moerman P. Pseudomyxoma peritonei originating from an intestinal duplication. Case Rep Pathol. 2013;2013:608016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |