Published online Sep 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i25.7445

Peer-review started: April 27, 2021

First decision: June 6, 2021

Revised: June 19, 2021

Accepted: July 19, 2021

Article in press: July 19, 2021

Published online: September 6, 2021

Processing time: 125 Days and 20.3 Hours

This case study describes an atypical presentation of avascular necrosis (AVN) of the first metatarsal head, which is largely unfounded in the literature.

A healthy 24-year-old female initially presented with pain at the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ) and was diagnosed with AVN by physical examination and magnetic resonance imaging. The patient demonstrated atypically poor progress in recovery, despite being in otherwise good health and being of young age, with no history of corticosteroid or alcohol use. The patient also did not have any history or clinical features of autoimmune disease or vasculitis, such as systemic lupus erythematosus. The patient was managed with conservative treatment for 18 mo, which allowed for gradual return of full range of motion of the first MTPJ and subsiding pain, permitting the patient to return to high-intensity sports training and full weight-bearing. Throughout her recovery, many differential diagnoses were ruled out through specific investigations leading to further reinforcement of the diagnosis of AVN of the 1st metatarsal head.

Atypical AVN may occur with no predisposing risk factors. Treatment is mainly conservative, with unclear guidelines in literature on management.

Core Tip: Although idiopathic avascular necrosis (AVN) of the first metatarsal head is uncommon, its risk factors and clinical management can vary widely between sites. The present case of AVN of the first metatarsal head occurred in a 24-year-old female adult with pain in the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Initially, conservative treatment with analgesics did not show much improvement in relieving pain. However, after continuous treatment for 2 mo, the swelling subsided with reduced pain. After 4-mo of follow-up monitoring, improved range of motion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint was observed, but the pain had disappeared. No other complications developed during 18-mo of follow-up monitoring. The purpose of this case report is to indicate that an efficient and precise diagnosis of the patient’s case is important as it significantly changes the prognosis and management for such a condition.

- Citation: Siu RWH, Liu JHP, Man GCW, Ong MTY, Yung PSH. Avascular necrosis of the first metatarsal head in a young female adult: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(25): 7445-7452

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i25/7445.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i25.7445

The present case of avascular necrosis (AVN) of the first metatarsal (MTT) head occurred in a young, healthy female adult with pain of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Initially, conservative treatment with analgesics did not show much improvement in relieving pain. However, after continuous treatment for 2 mo, the swelling subsided with reduced pain. After 4 mo, improved range of motion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint was observed and pain had subsided. An efficient and precise diagnosis of the patient’s case is important as it significantly changes the prognosis and management for such a condition.

AVN, also known as osteonecrosis, is a pathologic process involving the compromise of bone vasculature leading to the death of bone and marrow cells[1]. It is not a rare diagnosis and can involve several locations in the skeletal system[2]. The process is most often progressive, resulting in joint destruction within a few months to two years in the majority of patients[3]. In the United States alone, approximately 20000-30000 new cases are reported annually[4]. However, the exact cause of AVN remains to be elucidated. Although the most common sites of AVN in the foot are the second MTT head (Freiberg disease), calcaneus (Sever disease) and talus (Dias disease), it is not exceptional to occur at the first MTT head[5]. In adults, the most common cause of AVN of the first MTT head secondarily arose from iatrogenic insult to vascularity by a distal first MTT osteotomy (Mitchell osteotomy) for correction of hallux valgus deformity[6]. There are two current literature reports on bilateral first MTT head idiopathic AVN in adolescents[7,8]. As there is currently no literature reports on unilateral idiopathic first MTT head AVN in adult patients, the present study aims to describe a new case of unilateral idiopathic AVN of the first MTT head in an adult patient.

A 24-year-old woman, a recreational rugby player, attended our outpatient clinic on May 2017, complaining of right big toe pain.

Patient denied of any history of trauma. Patient was not suffering from a fever, nor had any history of alcohol or any other substance abuse, and no history of corticosteroid use.

Patient experienced good past health. She did not have any history of trauma to the right foot, nor have any history of vasculitis, Caisson Disease or alcoholism. She did not take any medication (including corticosteroids) and had no known allergies.

No significant personal or family history was noted.

On physical examination, mild swelling of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ) was revealed, with failed active interphalangeal joint flexion to 0 degrees. Passive range of motion was full. Tendons of Flexor Hallucis Longus were intact. Clinical appearance of the feet, sensation and local perfusion of the toes were normal. No significant impairment to activities of daily living were noted. Weight-bearing was affected by pain.

No laboratory testing was conducted.

X-ray films of the foot did not show any obvious fractures or bony defects; therefore a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed.

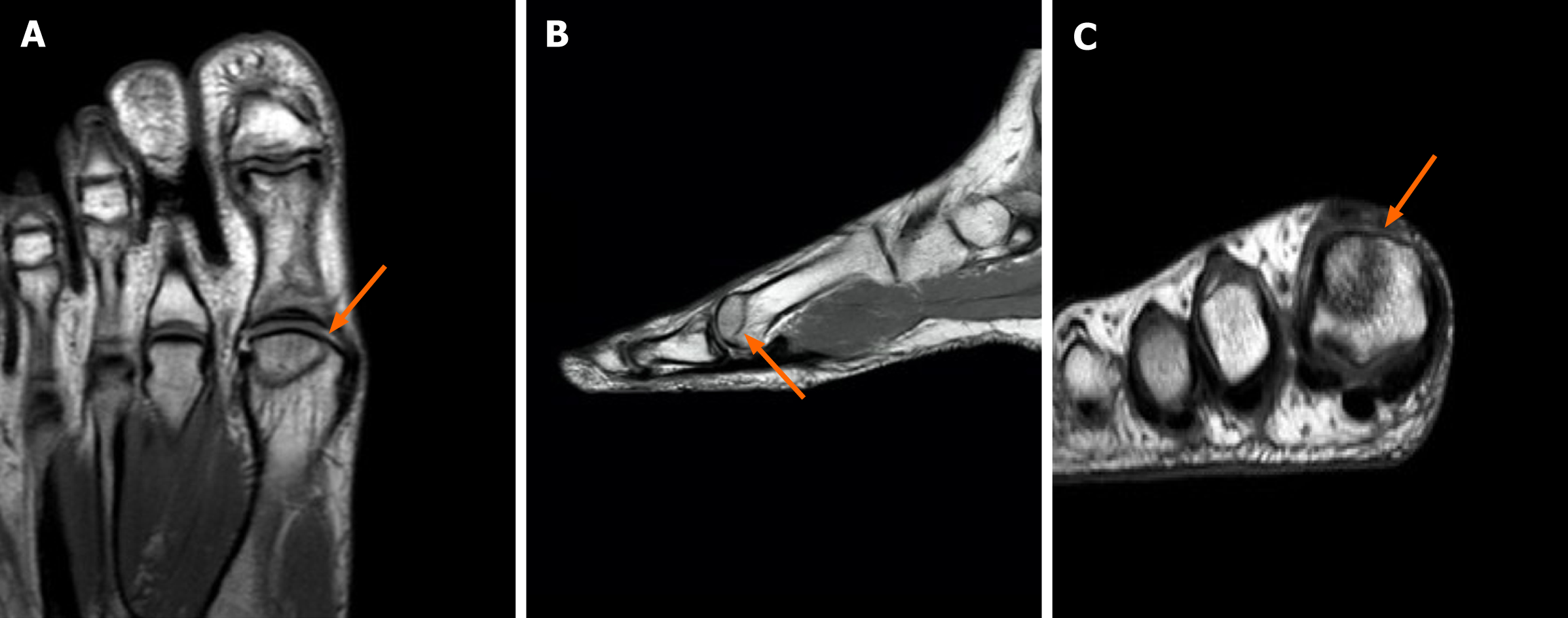

MRI of the right big toe showed an abnormal linear signal within the marrow cavity of the first MTT head, along with a suspected serpiginous line with bony oedema present at the dorsal aspect of both the distal phalangeal base and proximal phalangeal head (Figure 1).

Supplementary computed tomography (CT) scan showed no fracture line, however, did show diffuse sclerosis at the MTT head. Cartilage was grossly intact. The impression was early AVN of the first MTT head with bony oedema related to previous contusion or healing MTT fracture.

The final diagnosis is AVN of the first right MTT head.

Conservative treatment was initiated with non-weight bearing exercises and analgesics. Paracetamol 1000 mg tablets and Ibuprofen 200 mg tablets were taken pro re nata. Non-weight bearing exercises were conducted with the use of bilateral elbow crutches for ambulation initially. Partial weight-bearing with single elbow crutch was commenced once pain symptoms have gradually reduced to a NRS level of < 5/10. Once patient was able to fully weight-bear with minimal pain (NRS 1-2/10), she was put on full weight -bearing protocol with no walking aids. Analgesics were continued to be given for pain relief during physical exercise and cross training. No deterioration or aggravation of pain symptoms occurred with this rehabilitation protocol.

The outcome of the follow-up is shown in Table 1.

| Timepoint | Remarks |

| First presentation (May 2017) | The patient first presented with right big toe pain. Physical examination revealed mild swelling of the first MTPJ, with failed IPJ flexion, but intact FHL tendon. Clinical appearance of the feet, sensation and local perfusion of toes were normal |

| Pain NRS of 7-8/10 was noted. Patient was put on bilateral elbow crutches for walking aid | |

| 1 wk later (May 2017) | Physical examination and CT scan both showed unchanged condition with continued pain and swelling. Overall features still implied either diagnosis was healing AVN or healing fracture |

| Pain NRS of 3-4/10 was noted. Patient was stepped down to partial weight bearing protocol with unilateral elbow crutch | |

| 2 mo later (July 2017) | Swelling subsided. CT scan revealed no serial changes. The abnormal linear signal within the marrow cavity of the first MTT head remained. Although mild joint effusion of the first MTPJ remained, no observable progression or regression of serpiginous line was seen |

| Pain NRS of 1-2/10 was noted. Patient was allowed to conduct full weight bear | |

| 14 mo later (July 2018) | CT scan and MRI showed a reduction in bony oedema. The abnormal linear signal within marrow cavity of first MTT head, dorsal aspect of distal phalangeal base and proximal phalangeal head remained visible |

| 18 mo later (November 2018) | Final follow-up: The patient reported slight improvement of her right toe pain, with slight tenderness observed upon palpation. Range of motion of the first MTPJ had improved with only a 10 degree deficit in flexion without swelling, redness or local heat |

| Characterisation of the improvement of anatomical morphology by radiological assessments (CT scan and MRI) remained the same. The patient reported that she was able to undergo cross-training during the past ten months. However, she was not able to return to rugby activities. Thus, advise was given to the patient to continue cross-training as tolerated. Anatomical investigation of the toe remained unchanged | |

| Upon physical examination, tenderness continued to be experienced over the first MTT head. However, the patient was able to return to high-intensity training. She experienced no pain during rest or active flexion and extension, with only mild aching after training | |

| Last follow-up (November 2018) | Mild tenderness remained, with full range of motion of first MTPJ achieved. Patient able to return to high-intensity training with mild aching after each session |

At follow-up one week later, physical examination and CT scan both showed unchanged condition with continued pain and swelling. Overall features still implied either healing AVN or healing fracture. Conservative treatment was continued for another month when she complained of pain on her right toe. Patient was put on partial weight bear protocol with unilateral elbow crutch.

At 2 mo after attending our clinic, swelling had subsided and CT scan revealed no serial changes. The abnormal linear signal within the marrow cavity of the first MTT head remained. Although mild joint effusion of the first MTPJ remained, no observable progression or regression of the serpiginous line was seen. As a result, conservative treatment and analgesics were continued. Patient was able to fully weight bear at this point.

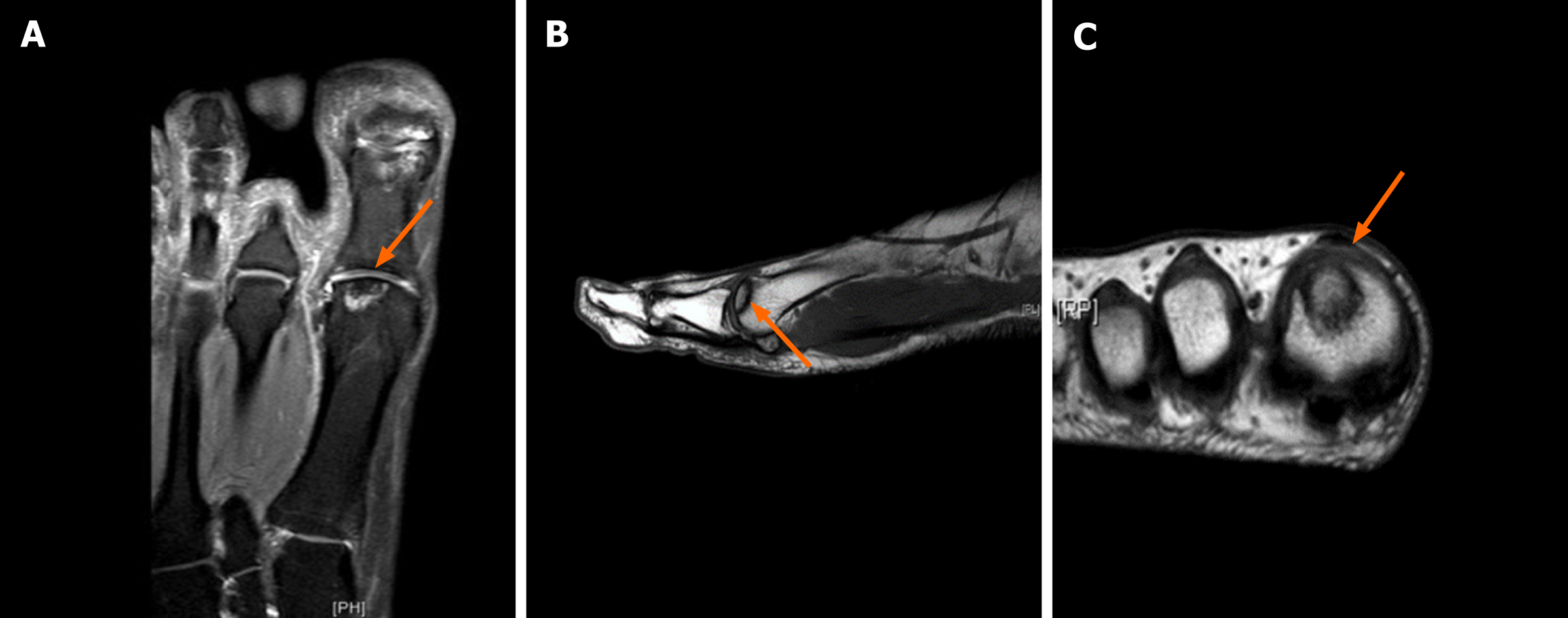

At 14 mo follow-up, both CT scan and MRI showed a reduction in bony oedema. The abnormal linear signals within the marrow cavity of first MTT head, dorsal aspect of the distal phalangeal base and proximal phalangeal head remained similar (Figure 2).

In the following 4-mo, the patient reported slight improvement of her right first toe pain, with slight tenderness observed upon palpation. The range of motion of the first MTPJ had improved with only a 10 degree deficit in flexion without swelling, redness or local heat. Characterisation on the improvement of anatomical morphology by radiological assessments (CT scan and MRI) remained the same. Herein, the patient reported that she was able to undergo cross-training during the past 10-months. However, she was not able to return to rugby activities. Thus, advise was given to the patient to continue cross-training as tolerated.

On the last consultation visit on November 2018, which was 18-mo after first visit, anatomical investigation of the toe remained similar. Upon physical examination, tenderness was still experienced over the first MTT head. However, the patient was able to return to high-intensity training. She experienced no pain during rest or active flexion and extension, with only mild aching after training.

Although no clear explanation can be given regarding the occurrence of AVN in our patient, it cannot be excluded based on possible previous history of trauma to the lesion site, owing to her high-intensity training as a recreational athlete. It is, however, interesting and perhaps perplexing, for a patient with such good health, young age and no history of corticosteroid or alcoholic use to have stagnant progress in recovery. As the age of AVN onset is more common between 30- to 50-year-olds, our young female patient (in her mid-twenties) is considered an exceptional case. Likewise, the occurrence of AVN in females are often associated with a background of SLE[9]; however, our patient is of good health with no history or clinical features suggestive of such.

To date, no current literature exist regarding the risk factors or prevalence of atypical site AVN. The classical approach is to diagnose AVN by MRI, noting the presence of diffuse oedema, a reactive interface line and serpiginous line. Yet, the presentation of such features is far from ascertaining the diagnosis of an atypical AVN. Hence, Smillie’s Classification for Freiberg’s Disease may likely be the best AVN classification protocol that could be adopted to assess the severity of our patient’s condition[10]. Adopting and drawing from this classification, we propose a five-stage model. Stage 1 represents a fracture in the epiphysis with sclerosis between the cancellous surfaces; stage 2 represents MTT head flattening as the dorsal aspect articular cartilage sinks; stage 3 represents structural compromise of the MTT head with further absorption and sinking of articular cartilage, with bony projections medially and laterally; stage 4 represents that restoration of the normal anatomy of MTT head has passed; and stage 5 represents arthrosis with flattening and deformities of the MTT head. Based on these criteria, our patient’s condition remains at the earlier classifications, either stage 1 or 2, indicative of receiving conservative measures instead of surgical treatment[11]. Due to the rareness of this condition, there is no obvious procedure for differentiation of its diagnosis. However, a number of conditions tend to exhibit a similar presentation and chief complaint, as in our patient. Differential diagnoses such as stress fracture, gouty arthritis, subchondral fracture with non-union, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), hallux rigidus arising from degenerative arthritis, and bone marrow oedema syndrome (BMES) are all compatible with the clinical presentation and imaging results of our patient.

Stress fracture is one of the more important differential diagnoses of this case. This condition, however, would not present with the characteristic appearances on imaging found in AVN. A fracture line, accompanied by periosteal and soft tissue oedema, can also be found in an MRI of a stress fracture, yet, a serpiginous line is unlikely to be present[8,12]. The differentiation between a stress fracture and AVN of first MTT is important, as the management approach for both are extremely different. The general approach to a stress fracture would be rest and prevention of weight-bearing activities[13].

A subchondral fracture refers to a stress fracture occurring below the joint cartilage, commonly seen in femoral head and knee joints, but also reported in MTT heads (most commonly the 2nd MTT). The condition is characterised by slow healing[14], a similar MRI presentation of a serpiginous line[15], and an associated marrow oedema-like pattern[16], which were present in our patient. Fracture non-union can be excluded due to the absence of blurred fracture margins and external callus formation on CT[17]. Further differentiation is possible, as the patient did not present with MTT head flattening[16]. The management approach to such pathology would resonate with a similar approach to that of a stress fracture.

Gouty arthritis commonly presents with pain, swelling, redness and warmth at the first MTPJ[18]. In any case of hallux pain, gout cannot be excluded without a prior serum uric acid test (normal: ≤ 6.0 mg/dL in women)[19]. Although being overweight is a risk factor[20], gout would seem unlikely for our premenopausal patient with no medication usage or chronic disease. Nevertheless, if the patient suffered from gouty arthritis, a purine-free or low protein diet, along with uric acid-lowering medication, must be implemented as part of the management plan during treatment.

Although Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is also unlikely to occur in our young patient, it cannot be immediately excluded owing to a presentation of local pain, oedema, redness and limited range of motion[21]. Similarly, there is no gold standard for diagnosing RA. Based on the guidelines of the American College of Rheumatology, diagnosis is proposed through clinical presentation plus various serum results, such as presence of Rheumatoid factor, Anti-CCP antibodies, elevated C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Laboratory assessment was not conducted on this patient owing to low suspicion of autoimmune related cases, yet the diagnosis of RA must be considered if patient was to deteriorate with our given management plan. Further implications of RA include the presentation of bone erosion and bone oedema on imaging with joint space narrowing[22]. Imaging modalities can effectively reveal if the lesion is confined to first MTT head, rather than the MTPJ[23]. Although RA is unlikely to be the diagnosis in this case, it is worth noting the differences in the treatment approaches of a patient with AVN in comparison to a systemic disease, such as RA. For patients with RA, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are recom

Degenerative arthritis leading to hallux rigidus (HR) is another condition presenting with pain, stiffness and decreased range of motion[25]. HR, however, exhibits palpable exostosis[26] and radiographic evidence of MTT head flattening with subchondral sclerosis, in addition to joint space narrowing[27]. For these reasons, HR can be excluded in our patient. Management of HR would involve the use of orthotics and pads to restrict movement of the big toe, along with anti-inflammatory medications for pain relief[28].

Bone marrow oedema syndrome (BMES) may also be possible, due to radiographic evidence of oedema and localised debilitating pain[29]. Notably, BMES may occur concomitant to AVN and is not strictly a differential diagnosis[30]. BMES is characterized by high bone marrow signal intensity on fluid sensitive sequences on MRI. This is like what is seen on the MRI for our patient. Among all BMES, transient osteoporosis has been reported to be affecting only one skeletal site, similarly in our patient. However, it has also been cited to be associated with subclinical hypothy

In general, osteotomy and joint debridement are possible options to manage AVN in our reported case. However, the mild severity of our patient’s symptoms suggest that such a drastic approach might not be necessary. Decompressive procedures, bone grafting and joint replacement exist as other treatment options of AVN. These treatments, however, are more commonly used in the management of the typical sites of AVN, rather than the first MTT head. It has been illustrated that pressure at the mid-forefoot beneath the second to fourth MTT head is higher than the mean pressures of the medial and lateral aspects of the forefoot, namely the first and fifth MTT head respectively[33]. Thus, it is appropriate to initially treat this patient with nonoperative methods eliminating weight-bearing stress rather than adopting operative treatments to correct fractures or deficient blood supply as seen in AVN in typical sties.

Moreover, the main concern of our patient was not the deficit in range of motion, but the pain that resulted from cross-training. Therefore, this pain can be adequately controlled by Paracetamol and NSAIDs to allow the patient to return to play and also prevent unnecessary risks and possible complications from operative treatment. Even though the patient continued to worry about returning to her original intensity of training level, she displayed gradual improvements in her capacity of weight bearing and duration of play. As a result, the patient was placed on regular follow-up and conservative treatment with analgesics. In addition, a weight loss programme, orthotic shoewear and restricted weight bearing can be considered. As her body mass index (BMI) was considered overweight (BMI = 25.2)[34], prescribing a weight loss programme may be beneficial in reducing stress on the hallux, which may enhance recovery.

In conclusion, an efficient and precise diagnosis of the patient’s case was important, as it significantly changed the prognosis and management of her condition, especially considering her involvement in sports. Currently, patient shows promising progress in returning to original play and recovery. However, there is a lack of clear return-to-play guidelines for lower limb injuries and conditions. It was therefore imperative that we provided the patient with instructions for future management. If patient becomes refractory to conservative management, step up to surgical options may be considered.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Eamsobhana P, Moretti A S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Mont MA, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: ten years later. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1117-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Enge Junior DJ, Fonseca EKUN, Castro ADAE, Baptista E, Santos DDCB, Rosemberg LA. Avascular necrosis: radiological findings and main sites of involvement - pictorial essay. Radiol Bras. 2019;52:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rajpura A, Wright AC, Board TN. Medical management of osteonecrosis of the hip: a review. Hip Int. 2011;21:385-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moya-Angeler J, Gianakos AL, Villa JC, Ni A, Lane JM. Current concepts on osteonecrosis of the femoral head. World J Orthop. 2015;6:590-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 5. | Aptekar RG, Klippel JH, Becker KE, Carson DA, Seaman WE, Decker JL. Avascular necrosis of the talus, scaphoid, and metatarsal head in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;127-128. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Skoták M, Behounek J. [Scarf osteotomy for the treatment of forefoot deformity]. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2006;73:18-22. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Fu FH, Gomez W. Bilateral avascular necrosis of the first metatarsal head in adolescence. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;282-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gurevich M, Bialik V, Eidelman M, Katzman A. Avascular necrosis of the 1st metatarsal head. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2008;75:396-398. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Nevskaya T, Gamble MP, Pope JE. A meta-analysis of avascular necrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence and risk factors. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35:700-710. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Smillie IS. Treatment of Freiberg's infraction. Proc R Soc Med. 1967;60:29-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Carmont MR, Rees RJ, Blundell CM. Current concepts review: Freiberg's disease. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marshall RA, Mandell JC, Weaver MJ, Ferrone M, Sodickson A, Khurana B. Imaging Features and Management of Stress, Atypical, and Pathologic Fractures. Radiographics. 2018;38:2173-2192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pegrum J, Crisp T, Padhiar N. Diagnosis and management of bone stress injuries of the lower limb in athletes. BMJ. 2012;344:e2511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gourlay ML, Renner JB, Spang JT, Rubin JE. Subchondral insufficiency fracture of the knee: a non-traumatic injury with prolonged recovery time. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Polesello G, Sakai DS, Ono NK, Honda EK, Guimaraes RP, Júnior WR. The importance of the diagnosis of subchondral fracture of the femoral head, how to differentiate it from avascular necrosis and how to treat it. Rev Bras Ortop. 2009;44:102-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Bredella MA, Ouellette H. MRI of metatarsal head subchondral fractures in patients with forefoot pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:570-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Morshed S. Current Options for Determining Fracture Union. Adv Med. 2014;2014:708574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ragab G, Elshahaly M, Bardin T. Gout: An old disease in new perspective - A review. J Adv Res. 2017;8:495-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 307] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang ML, Gao YX, Wang X, Chang H, Huang GW. Serum uric acid and appropriate cutoff value for prediction of metabolic syndrome among Chinese adults. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2013;52:38-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Singh JA, Reddy SG, Kundukulam J. Risk factors for gout and prevention: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:192-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Guo Q, Wang Y, Xu D, Nossent J, Pavlos NJ, Xu J. Rheumatoid arthritis: pathological mechanisms and modern pharmacologic therapies. Bone Res. 2018;6:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 575] [Cited by in RCA: 1004] [Article Influence: 143.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Heidari B. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Early diagnosis and treatment outcomes. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2:161-170. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Mackenzie AH. Differential diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 1988;85:2-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, Paulus HE, Mudano A, Pisu M, Elkins-Melton M, Outman R, Allison JJ, Suarez Almazor M, Bridges SL Jr, Chatham WW, Hochberg M, MacLean C, Mikuls T, Moreland LW, O'Dell J, Turkiewicz AM, Furst DE; American College of Rheumatology. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1029] [Cited by in RCA: 1025] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Brantingham JW, Wood TG. Hallux rigidus. J Chiropr Med. 2002;1:31-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Brantingham JW, Cassa TK. Manipulative and Multimodal Therapies in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Great Toe: A Case Series. J Chiropr Med. 2015;14:270-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ho B, Baumhauer J. Hallux rigidus. EFORT Open Rev. 2017;2:13-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Grady JF, Axe TM, Zager EJ, Sheldon LA. A retrospective analysis of 772 patients with hallux limitus. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92:102-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Arazi M, Yel M, Uguz B, Emlik D. Be aware of bone marrow edema syndrome in ankle arthroscopy: a case successfully treated with iloprost. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:909.e1-909.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Patel S. Primary bone marrow oedema syndromes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:785-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Paoletta M, Moretti A, Liguori S, Bertone M, Toro G, Iolascon G. Transient osteoporosis of the hip and subclinical hypothyroidism: an unusual dangerous duet? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21:543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Geith T, Niethammer T, Milz S, Dietrich O, Reiser M, Baur-Melnyk A. Transient Bone Marrow Edema Syndrome versus Osteonecrosis: Perfusion Patterns at Dynamic Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging with High Temporal Resolution Can Allow Differentiation. Radiology. 2017;283:478-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Luger EJ, Nissan M, Karpf A, Steinberg EL, Dekel S. Patterns of weight distribution under the metatarsal heads. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:199-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lim JU, Lee JH, Kim JS, Hwang YI, Kim TH, Lim SY, Yoo KH, Jung KS, Kim YK, Rhee CK. Comparison of World Health Organization and Asia-Pacific body mass index classifications in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2465-2475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |