Published online Aug 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i24.7123

Peer-review started: December 28, 2020

First decision: May 6, 2021

Revised: May 18, 2021

Accepted: June 4, 2021

Article in press: June 4, 2021

Published online: August 26, 2021

Processing time: 238 Days and 16.8 Hours

Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disease caused by germline mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) protein gene, which usually manifests as cutaneous fibrofolliculoma, pulmonary cysts, renal cell carcinoma, and spontaneous pneumothorax.

A 26-year-old woman with no history of smoking was admitted to the Respiratory Department of our hospital due to intermittent wheezing that lasted for 8 mo. She had experienced recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax more than four times during the past 8 mo. After admission, the patient again suffered from left pneumothorax without a clear reason. Lung computed tomography (CT) showed multiple low-density cystic changes in both lungs. Physical examination on admission revealed multiple white dome-shaped papules in the neck, the nape, and behind the ear. In addition, the patient had a family history of spontaneous pneumothorax. Her mother had suffered from pneumothorax four times (at age 36, 37, 42, and 50 years). Her second maternal aunt had suffered from a right pneumothorax at the age of 40. The multidisciplinary diagnosis of BHD, which included the Respiratory Department, Radiology Department, Pathology Department, and Dermatological Department, was BHD and was later confirmed by family genetic testing. The same variation (FLCN gene) was found in the patient’s mother and aunt.

This case highlights the importance of multidisciplinary diagnosis and a treatment platform for the diagnosis of BHD.

Core Tip: Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome involves multiple organs and systems of the human body, with complex and diverse clinical manifestations. In addition, physicians lack sufficient knowledge and experience in the diagnosis and treatment of this rare disease. This case highlights the importance of establishing a multidisciplinary diagnosis and treatment platform for the clinical diagnosis and treatment process, which is of great significance for the accurate identification of BHD.

- Citation: Lu YR, Yuan Q, Liu J, Han X, Liu M, Liu QQ, Wang YG. A rare occurrence of a hereditary Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(24): 7123-7132

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i24/7123.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i24.7123

Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disease caused by germline mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) protein gene. The incidence of BHD syndrome is still unclear. At present, approximately 200 families with BHD with pathogenic FLCN mutations have been reported worldwide[1]. These patients usually present with cutaneous fibrofolliculoma, pulmonary cysts, renal cell carcinoma, and spontaneous pneumothorax. Spontaneous pneumothorax is considered the most common manifestation. It has been estimated that up to 5%-10% of individuals with primary spontaneous pneumothorax have underlying BHD[2].

Herein, we report a case of a 26-year-old female patient from China who had recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax due to genetic predisposition.

A 26-year-old woman with no history of smoking presented to the Respiratory Department of our hospital due to intermittent wheezing that lasted for 8 mo.

The patient had developed recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax more than four times during the past 8 mo, but had no fever, chest pain, or hemoptysis. The patient occasionally experienced cough, mild panting, and suffocation. In January 2018, the patient experienced mild panting and developed dyspnoea for the first time. Chest X-ray showed left pneumothorax, after which left closed thoracic drainage was performed. In May 2018, the patient presented with mild panting and suffocation. Chest X-ray showed left pulmonary pneumothora and mild left lower lung atelectasis. Pulmonary bulla resection was performed under thoracoscopy and general anaesthesia. After surgery, the pathological findings showed blood stasis of the lung tissues, alveolar ectasia and fusion, bullous formation, proliferation of fibrous tissue of the blister wall, and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration. In July and August 2018, the patient suffered from pneumothorax in the left lung.

According to the patient, she was diagnosed with allergic purpura at the age of 14 and had proteinuria for 8 years.

Physical examination revealed no abnormalities. The lung sounds were clear bilateral.

After admission to our hospital, routine urinary microscopy showed occult blood 2+. Respiratory-associated tumour marker was confirmed to be squamous-cell carcinoma 3.30 µg/L. Arterial blood gases, complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were all within normal limits.

The patient’s lung computed tomography (CT) examination showed low-density cystic changes in the right lung, left lung, and interlobular fissure (Figure 1). After admission, the patient suffered from left pneumothorax again without a clear reason. The bedside chest radiograph indicated that the left lung tissue was compressed by 30% (Figure 2). Abdominal ultrasound and abdominal and pelvic enhanced CT showed no renal tumour but a high-density shadow on the right liver (the right abdomen) (Figure 3).

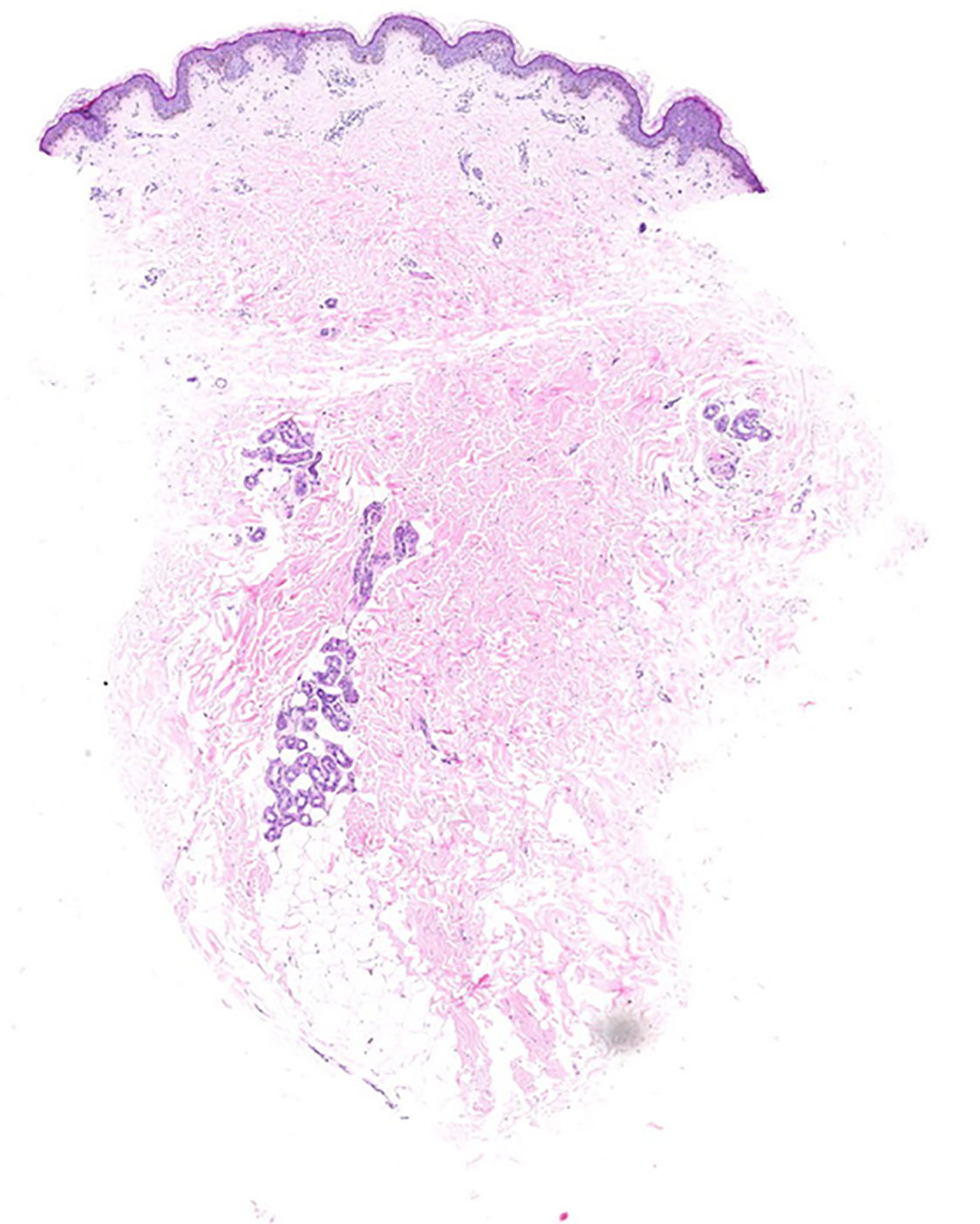

The patient underwent pulmonary bulla resection under video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and pleurodesis under the guidance of general anaesthesia. The postoperative pathological reports displayed pulmonary emphysema-like changes with pulmonary bullae formation and small interlobular septa in the partially enlarged cystic cavity. Normal lung tissue had partial interstitial congestion (Figure 4).

In addition, the patient had a family history of spontaneous pneumothorax. The patient’s mother and her second maternal aunt had suffered from recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax in the past. The mother had the worst condition, which manifested as lung-free marking and pleural line shadow in the right lung, the right lung being compressed into the hilar region by about 70%, compression into a strip-like solid shadow of the right lung, multiple thin-walled cavities of varied sizes in the whole lung (with the maximal length of about 79 mm at diameter), and a small amount of effusion in the right pleural cavity (Figure 5).

Her second maternal aunt developed right pneumothorax at the age of 40. To review the common features, the patient, her mother, and her second maternal aunt underwent chest CT. The results revealed pulmonary alveolar or cystic changes in all of the subjects. In addition, the chest and abdominal CT of her first maternal aunt indicated a saccular shadow of the right lower lobe and a possible left renal hamartoma. Her uncle (mother’s brother) had no pulmonary bulla or cystic changes or lesions in the kidney.

Multiple white dome-shaped papules with a diameter of < 0.5 mm were found on the anterior and posterior neck and the posterior side of the ears of the patient (Figure 6). Meanwhile, multiple white dome-shaped papules were found on the mother’s and her second maternal aunt’s necks, cheeks, and posterior ears (Figure 7). The dermatologist considered that the patient’s papules conformed to the appearance of fibrofolliculomas but required pathological confirmation. Mild infiltration of lymphocytes around the vessels in the superficial dermis with melanophage showed dominant findings in the pathological specimens of the patient’s skin (Figure 8).

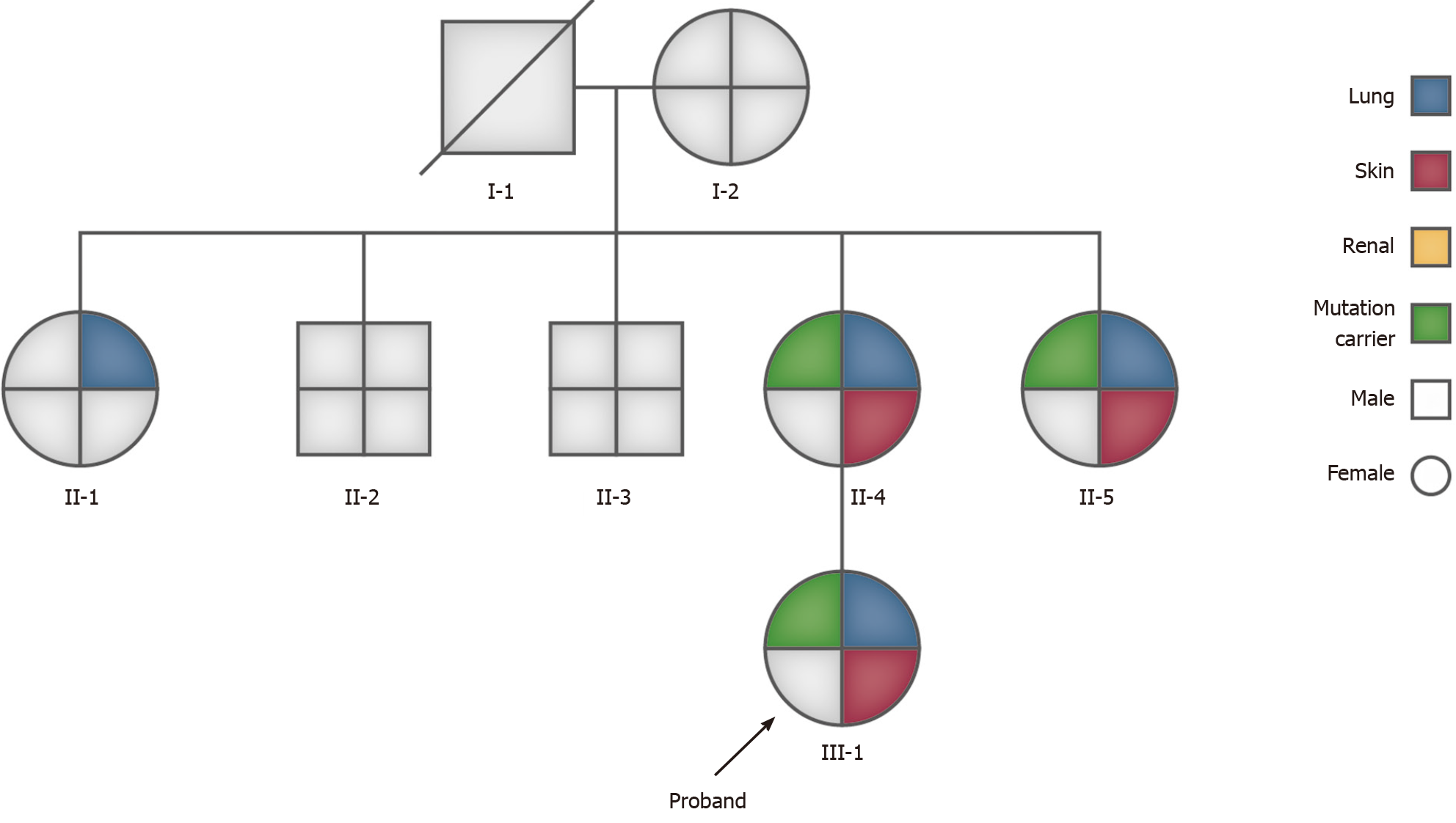

Due to the patient’s history of recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax, multiple skin papules, cystic lesions in the lungs, and a family history of pneumothorax, we suspected a congenital disease, particularly BHD. The family tree is shown in Figure 9.

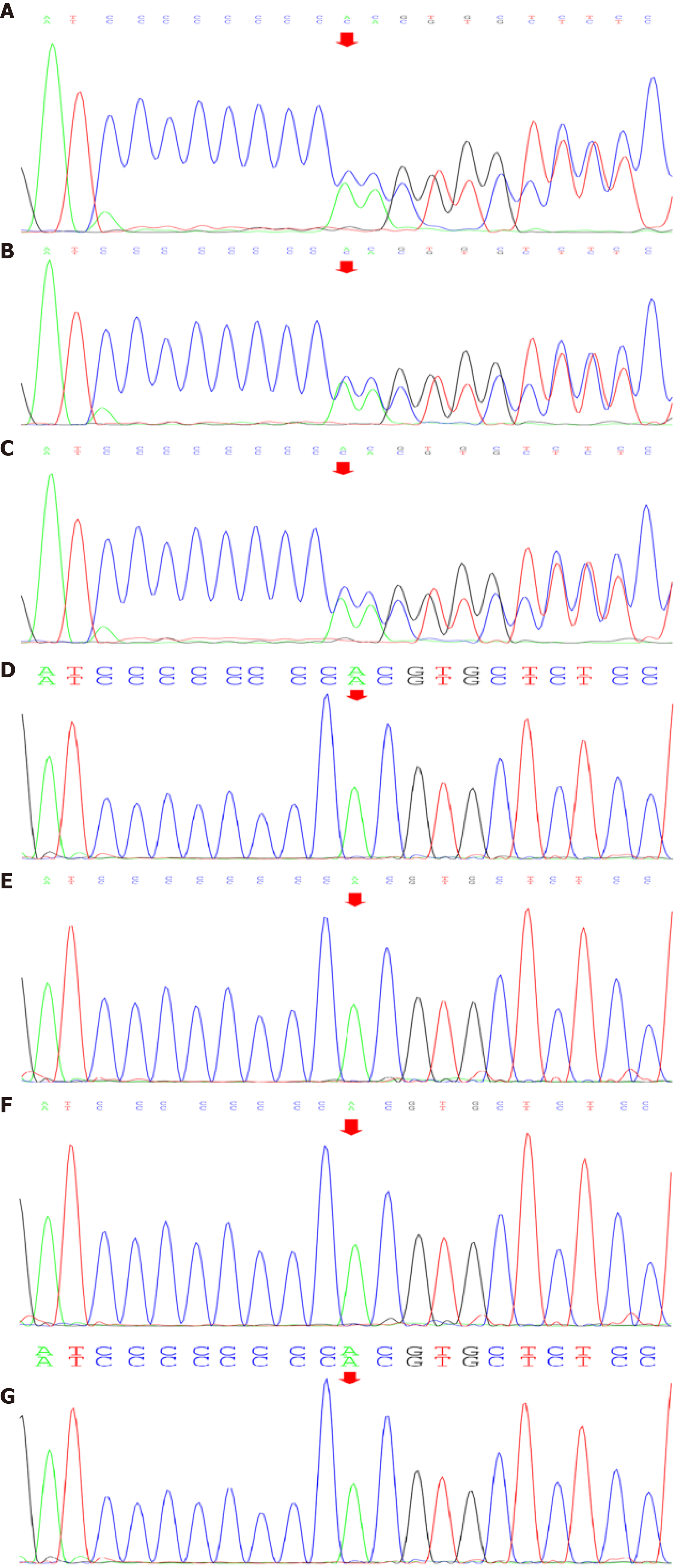

After obtaining written informed consent from the patient and her family, we accomplished the family genetic test for BHD. Seven of the family members underwent genetic analysis, which included extracting the genomic DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes. The results showed that the patient’s FLCN gene was located on chromosome 17. The nomenclature of the variant was c.1285dup. The heterozygous nucleotide variation of c.1285_1286insC (interpolation of C at 1285_1286 nucleotides of the coding region) was found in the FLCN gene of the subject. This mutation occurred due to a change in amino acid synthesis starting from amino acid His, No. 429, and terminating at 27th amino acid after the change p. (His429Profs*27) as a frameshift variant, which we believe affected the protein function. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics rating suggested PVS1 and PM2 by taking into consideration the suspected diseases (Figure 10). The genetic test of the patient’s mother also showed mutations in this site, considering that the variation of the patient’s FLCN gene was derived from her mother. The pathogenicity of this mutation has been reported in the literature and is associated with BHD syndrome[3].

The final diagnosis of the presented case was BHD syndrome.

The patient developed pneumothorax five times during the hospital stay from January to August 2018, and the interval between pneumothorax attacks was gradually shortened. On August 2, 2018, the patient underwent closed thoracic drainage. On August 22, pneumothorax in the left lung occurred again with only a 20-d interval. In September 2018, the patient underwent pulmonary bulla resection by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and pleurodesis under general anaesthesia.

The patient recovered after surgery. To date, no pneumothorax has occurred. The patient is still being followed up for evaluation of her long-term condition.

BHD is a rare autosomal dominant inherited disorder caused by germline mutations in the FLCN protein gene located on the 17p11.2 chromosome. This variation is not regarded as a polymorphic change and occurs at an extremely low frequency in the population. For this type of inheritance, a possible factor might be a heterozygous variation. FLCN regulates the signalling pathway of the mammalian rapamycin target, thereby regulating cell growth and metabolism. FLCN messenger ribonucleic acid is expressed in the cells of main organs including skin, kidney, lung, and pancreas. In Asia and Europe, several types of germline FLCN mutations have been found in patients with BHD syndrome. The FLCN gene consists of 14 exons. The insertion or deletion of C8 cytosine (c.1285dupC) in exon 11 has been detected in many BHD patients and is considered the most common mutation[3,4]. Exon 9 mutations are closely associated with tumorigenesis[5].

Skin changes usually occur in patients with BHD after the age of 20, typically manifesting as multiple fibrofolliculoma, trichodiscoma, and soft fibroma. The skin lesions are mainly found on the cheeks, nose, and neck skin[6]. Although BHD skin lesions present as a rather typical and relatively simple appearance, these lesions are often misdiagnosed as acne (delayed acne), multiple miliaria, or multiple sebaceous cysts; thus, the correct diagnosis may be delayed for years[7]. In this case, there was no clear fibrofolliculoma in the papule. A retrospective study of 62 Asian patients with BHD showed that they presented with less typical skin changes[8].

The lungs are the main organs involved, and the condition mainly manifests as pulmonary cysts and recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax. Our patient was admitted to the hospital because of pneumothorax recurrence. Previous studies have shown that more than 80% of adult BHD patients present with multiple pulmonary cysts under chest CT scans. Compared with primary pneumothorax (pulmonary cyst usually located in the apical region), the predilection sites of BHD are mainly located in the middle and lower lung fields and may also involve the rib angle[9,10]. Typically, chest CT shows multiple, thin-walled cysts with clear margins in both lungs. The size of the cysts varies from a few millimetres to 2 centimetres or more; the pulmonary cysts in BHD syndrome appear oval, round, or irregularly shaped[11]. In this study, lung CT images showed diffusive cystic lesions, which also included pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), pulmonary langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (PLCH), and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP). The cysts in LAM were usually diffuse with a round shape, and the lung parenchyma between the lesions appeared normal. The shape of the PLCH cyst was irregular. The lesion range did not involve the basal lung region or rib angle, and the lung parenchyma between the lesions remains pulled and twisted. LIP cysts vary in size and shape and are often accompanied by the ground glass, nodules, thickness of interlobular septa, and mediastinal and hilar lympha

The kidney is a frequently involved organ in BHD, which manifests as oncocytoma, chromophobe cell tumour, papilloma, and clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. The prognosis of BHD syndrome mainly depends on the penetrance of renal cell carcinoma and the histological type of renal tumour[14]. Current studies have shown that surgical resection of preserved nephrons is the primary treatment for patients with BHD complicated with renal tumours. The timing of surgery remains critical, determining the renal function of patients after surgery and long-term prognosis[12]. The average age of renal malignancies in patients with BHD is 45-55 years. Although no renal tumour has been detected, the patient should be closely monitored and followed up, possibly undergoing regular reviews by abdominal ultrasound and CT every year to estimate the malignant renal lesions. In addition, patients’ family history should be examined.

Cystic lung disease and spontaneous pneumothorax might be the main clinical manifestations in Asian patients with BHD, while the involvement of skin and kidney are relatively rare. Therefore, for pulmonologists, the image differentiation of pulmonary cystic disease is particularly important to avoid delay in diagnosis and treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Respiratory system

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tanabe H, Wiratnaya IGE S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Menko FH, van Steensel MA, Giraud S, Friis-Hansen L, Richard S, Ungari S, Nordenskjöld M, Hansen TV, Solly J, Maher ER; European BHD Consortium. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1199-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Frøssing L, Pedersen L, Shaker S. [Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is a rare but important cause of pneumothorax]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2018;180. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lee JH, Jeon MJ, Song JS, Chae EJ, Choi JH, Kim GH, Song JW. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome in Korean: clinicoradiologic features and long term follow-up. Korean J Intern Med. 2019;34:830-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. FLCN: The causative gene for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Gene. 2018;640:28-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Palmirotta R, Donati P, Savonarola A, Cota C, Ferroni P, Guadagni F. Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome: report of two novel germline mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) gene. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:382-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Birt AR, Hogg GR, Dubé WJ. Hereditary multiple fibrofolliculomas with trichodiscomas and acrochordons. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1674-1677. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Steinlein OK, Ertl-Wagner B, Ruzicka T, Sattler EC. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: an underdiagnosed genetic tumor syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:278-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sahn SA, Heffner JE. Spontaneous pneumothorax. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:868-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 442] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Toro JR, Pautler SE, Stewart L, Glenn GM, Weinreich M, Toure O, Wei MH, Schmidt LS, Davis L, Zbar B, Choyke P, Steinberg SM, Nguyen DM, Linehan WM. Lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and genetic associations in 89 families with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1044-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee JE, Cha YK, Kim JS, Choi JH. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: characteristic CT findings differentiating it from other diffuse cystic lung diseases. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2017;23:354-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ryu JH, Tian X, Baqir M, Xu K. Diffuse cystic lung diseases. Front Med. 2013;7:316-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Okada A, Hirono T, Watanabe T, Hasegawa G, Tanaka R, Furuya M. Partial pleural covering for intractable pneumothorax in patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Clin Respir J. 2017;11:224-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hasumi H, Baba M, Hasumi Y, Furuya M, Yao M. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: Clinical and molecular aspects of recently identified kidney cancer syndrome. Int J Urol. 2016;23:204-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Benusiglio PR, Giraud S, Deveaux S, Méjean A, Correas JM, Joly D, Timsit MO, Ferlicot S, Verkarre V, Abadie C, Chauveau D, Leroux D, Avril MF, Cordier JF, Richard S; French National Cancer Institute Inherited Predisposition to Kidney Cancer Network. Renal cell tumour characteristics in patients with the Birt-Hogg-Dubé cancer susceptibility syndrome: a retrospective, multicentre study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |