Published online Aug 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i24.6964

Peer-review started: February 10, 2021

First decision: March 15, 2021

Revised: March 31, 2021

Accepted: July 6, 2021

Article in press: July 6, 2021

Published online: August 26, 2021

Processing time: 194 Days and 10.3 Hours

To discuss recurrence patterns and their significance in colorectal cancer. Preexisting medical hypotheses and the clinical phenomena of recurrence in colorectal cancer were evaluated and integrated. Colorectal cancer recurrence/ metastasis consists of two types: recurrence from the activation of dormant cancer cells and recurrence from postoperative residual cancer cells. These two recurrences have their own unique mechanisms, biological behaviors, responses to therapy, and prognoses. For type 1 recurrences, surgical resection should be considered. Type 2 recurrences should be managed systematically in addition to surgical resection. The two types of colorectal cancer recurrence should be evaluated and managed separately.

Core Tip: In this work, we proposed the recurrence/metastasis of colorectal cancer consists of two types: recurrence from activation of dormant cancer cells and recurrence from proliferation of post-operative residual cancer cells. These two recurrences have their own unique mechanisms, biological behaviors, response to therapy, and prognosis. For type 1 recurrences, surgical resection should be considered. Type 2 recurrences should be managed systematically, in addition to surgical resection. Our theory also suggests that the tumor-node-metastasis staging system should be re-evaluated.

- Citation: Wang R, Su Q, Yan ZP. Reconsideration of recurrence and metastasis in colorectal cancer. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(24): 6964-6968

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i24/6964.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i24.6964

Cancer recurrence and metastasis are the major causes of death in colorectal cancer (CRC). Metastasis occurs when cancer cells migrate from the primary cancer to another site. Metastasis can exist at the time the cancer is diagnosed (synchronous) or at a later time (metachronous). Cancer recurrence is defined as a previously eliminated cancer appearing again after surgery or chemoradiotherapy; metastasis most commonly accompanies recurrence. The prognosis of patients with a recurrence of CRC is highly variable. At present, no theory can explain the variations in survival after recurrence, but there is much speculation concerning tumor biological behavior.

Here, we propose that there are two types of recurrence in CRC. The first type is recurrence from reactivation of dormant cancer cells, whereas the second type is recurrence from the proliferation of postoperative residual cancer cells or undetectable microcancer lesions present at the time that the CRC is diagnosed. The characteristics of these two types of recurrence are different and they should therefore be evaluated and managed differently.

At present, there are many theories to explain the mechanism of cancer recurrence. The tumor dormancy theory holds that at the time the primary cancer is diagnosed, micrometastatic lesions already exist, and these dormant cancer cells can maintain a relatively stable status for months or years. During dormancy, the cancer cells either remain in the G0 stage or their proliferation and apoptosis maintain a balance, so the micrometastatic foci are stable and not large enough to be detected by imaging examinations, so the patient appears to be disease-free. When unknown factors alter the microenvironment or immune surveillance fails to inhibit the dormant cancer cells, the tumors grow. When dormant cancer foci grow large enough to be detected or cause symptoms, cancer recurrence can be confirmed.

In clinical practice, there should be another type of recurrence in CRC, which we named type 2 recurrence. Type 2 recurrence includes two scenarios. Scenario 1: The primary surgery does not achieve complete radical resection; there are residual cancer cells in the surgical bed or adjacent to it. Just after the surgery, there were too few residual cancer cells to be detected. As the residual cancer cells continuously proliferate, they eventually form a recurrent/metastatic lesion that can be detected by imaging or that causes clinical symptoms. Scenario 2: When CRC is diagnosed, micrometastatic lesions already exist but are too tiny to be detected and are considered “no metastasis” when evaluated by imaging. Therefore, the surgery may miss these undetectable micrometastatic lesions. As these pre-existing undetectable micrometastatic lesions grow, they eventually form a recurrent/metastatic lesion that can be detected by imaging or cause clinical symptoms.

Scenario 1 can happen in these conditions. Radical resections could be incomplete for several reasons. Advanced lower rectal cancers are more prone to having positive circumferential resection margins. Total mesentery excision is the standard surgical procedure for rectal cancers, but the range of routine total mesentery excision does not include the lateral lymph nodes or para-aortic lymph nodes. Therefore, cancer cells in the lateral or para-aortic lymph nodes could be left behind if the resection range does not include them.

The key difference between the two types of recurrence is whether recurrent cancer cells experience a dormant stage. In type 1, the cancer cells experience a dormant stage, and the reactivation of the dormant cancer cells is an accidental or random event. This “accident” makes recurrence more likely to be an isolated disorder, so resection of the recurrent lesions is more likely to be curative. In type 2, as nonradical resection of a tumor is more akin to shrinking the tumor, the residual cancer cells in the surgical bed or adjacent tissues continue to proliferate and disseminate, and by the time a recurrent lesion can be detected, it has already become a comprehensive disease. Resection of a type 2 recurrence is not adequate to cure this disorder.

It should be noted that for type 1, cancer recurrence means an altered microenvironment or failure of immune surveillance. In this case, it is possible that sequential recurrent lesions may appear.

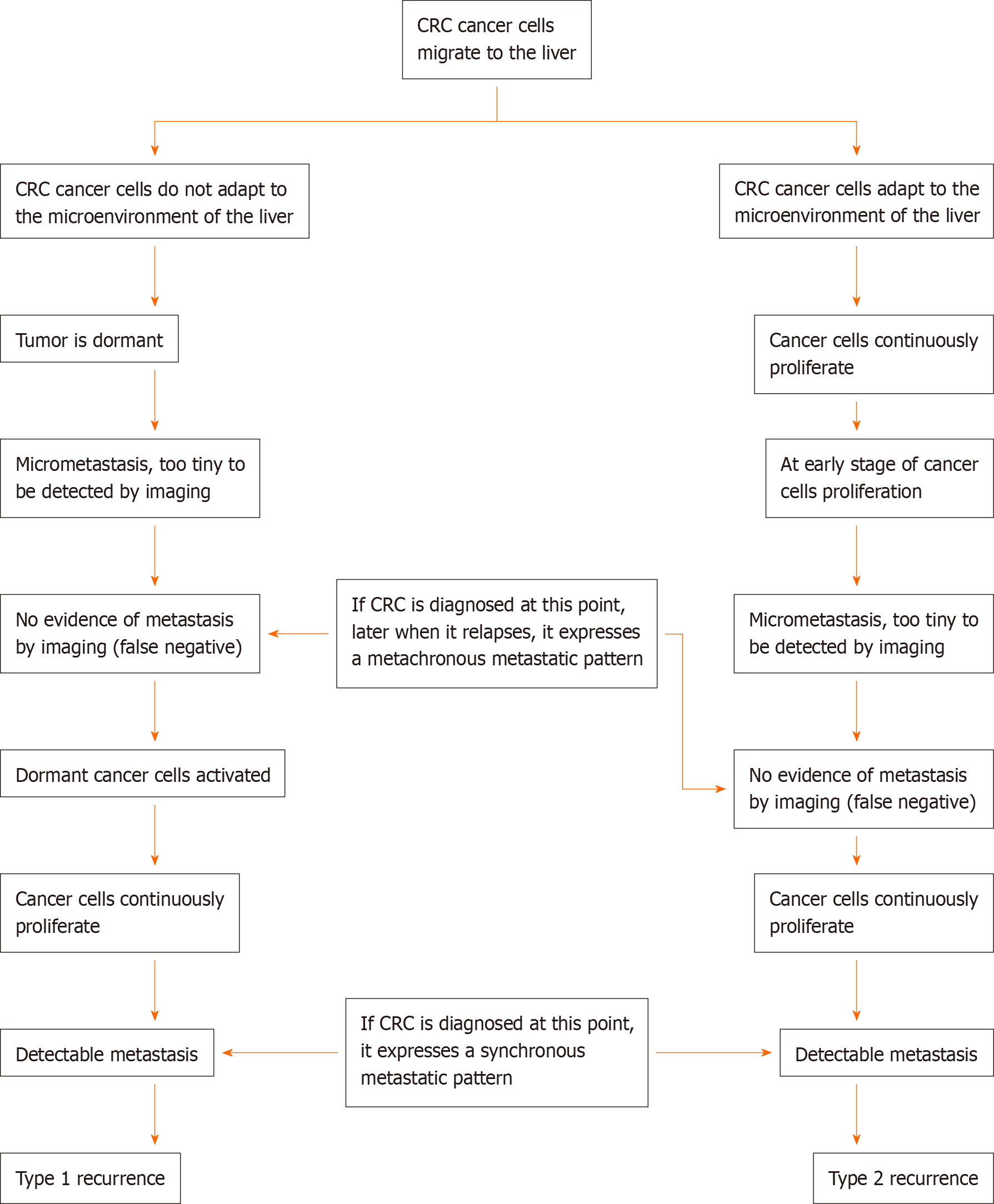

Typically, new metastatic lesions 3, 6, or 12 mo after primary surgery are defined as metachronous metastases. We propose that type 1 and type 2 recurrences have a crisscrossing relationship. Here, we evaluated liver metastasis of CRC as an example, as shown in Figure 1. For liver synchronous metastases, hematogenous disseminated cancer cells in liver lesions either experience a dormant stage or not, although they all manifest as intrahepatic lesions. For liver metachronous metastases, it may be that the cancer cells have already migrated to the liver and continuously proliferate, but at the time of imaging examination, the micrometastatic foci are not large enough to be detected; thus, it is considered as no metastasis (a false-negative). As proliferation continues, metastatic lesions appear. Alternatively, cancer cells maintain a dormant stage first, and after months or years, the dormant cancer cells reactivate to form detectable metastatic lesions.

The longer the time interval from no recurrence/metastasis to recurrence/ metastasis, the greater the possibility of a type 1 recurrence. We proposed that type 1 recurrence should have a relatively better prognosis than type 2 recurrence. We conclude that the prognosis of metachronous metastasis should be better than that of synchronous metastasis. It has been reported that the synchronous presence of primary colon cancer and liver metastasis may indicate a more disseminated disease status and is associated with a shorter disease-free survival than metachronous metastasis[1], which is consistent with our theory.

According to the definitions of the two types of recurrence, type 1 recurrence is more likely to be seen in distal organs or in the nonroutine surgical resection range, while type 2 recurrence is more likely to be seen in sites adjacent to the tumor bed, especially in the lymph flow drainage range. Additionally, type 1 recurrence is more likely to have a metachronous pattern, while type 2 recurrence is more likely to have a synchronous metastasis pattern.

The most common metastatic lesions of CRC are in the liver, lungs, and lymph nodes[2]. Less frequently observed metastatic lesions are in the ovaries or retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The different metastatic sites have varying prognoses. Ovary metastasis is a predictor of a poor prognosis, while lung metastasis has a relatively good prognosis. In selected patients, the resection of isolated para-aortic lymph node (IPLN) metastases can achieve a good prognosis.

IPLN metastasis is relatively rare compared with other metastases in CRC. According to our theory, synchronous IPLN metastasis more likely comes from the proliferation and progression of postoperative residual cancer cells, while metachronous IPLN may originate from the reactivation of dormant cancer cells. Hence, metachronous IPLN should have a better prognosis than synchronous IPLN metastasis. This conclusion is consistent with previous literature reports[3]. However, a systematic review reported that 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival appear to be relatively similar in synchronous IPLN and metachronous IPLN[4]. One explanation is that IPLNs are adjacent to the tumor bed; thus, IPLN metastasis and recurrence are a hybrid of type 1 and type 2.

Ovarian metastasis in CRC is a predictor of poor prognosis. It has been reported that this metastasis might occur through retrograde lymphatic spread and that the ovaries are among the first organs involved in this metastasis[5]. It is very likely for surgery to miss the retroperitoneal reticular lymph network and leave behind residual cancer cells. We can conclude that most ovarian recurrence/metastasis is from the proliferation of postoperative residual cancer cells, which is consistent with a poor prognosis.

The lung is an extra-abdominal organ in which the physiological environment is very different from that in the abdomen; therefore, metastatic cancer cells dwelling in the lungs are more likely to maintain a dormant status because of maladaptation to the microenvironment. As a result, lung recurrence/metastasis, according to our theory, is more prone to type 1 recurrence, which should have a relatively better prognosis after the resection of metastatic lesions. It has been reported that for the disease-free interval between primary colorectal surgery and lung metastasectomy, the longer the interval, the better the survival[6]. One explanation is that the longer the interval, the more likely it is to be a type 1 recurrence.

Oligometastasis is a concept proposed in 1995 that holds that cancer metastasis can have intermediate metastatic potential. During this stage, surgical resection of a metastatic lesion results in a relatively good prognosis[7]. According to our theory, type 1 recurrence is an accidental event in which the lesions are relatively few and manifest an oligometastatic phenotype. Type 2 recurrence is a comprehensive process in which cancer cells disseminate by implantation, lymph system spread, or direct invasion, which may result in multifocal metastatic lesions that are not consistent with an oligometastasis pattern. Hence, there is another explanation for oligometastases: the resection of oligometastases has a better prognosis because oligometastases are a form of type 1 recurrence.

Our theory presents a challenge to the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system. Currently, metastases are considered to be M stage, indicating a poor prognosis. However, the TNM system neither distinguishes synchronous or metachronous metastases nor distinguishes different mechanisms of recurrence. We propose that most metachronous metastases and a small portion of synchronous metastases develop from dormant cancer cells and should therefore be considered isolated disorders. In such cases, surgical resection may be the better option.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ogino S S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Tsai MS, Su YH, Ho MC, Liang JT, Chen TP, Lai HS, Lee PH. Clinicopathological features and prognosis in resectable synchronous and metachronous colorectal liver metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:786-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Arru M, Aldrighetti L, Castoldi R, Di Palo S, Orsenigo E, Stella M, Pulitanò C, Gavazzi F, Ferla G, Di Carlo V, Staudacher C. Analysis of prognostic factors influencing long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2008;32:93-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Choi PW, Kim HC, Kim AY, Jung SH, Yu CS, Kim JC. Extensive lymphadenectomy in colorectal cancer with isolated para-aortic lymph node metastasis below the level of renal vessels. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wong JS, Tan GH, Teo MC. Management of para-aortic lymph node metastasis in colorectal patients: A systemic review. Surg Oncol. 2016;25:411-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chang TC, Changchien CC, Tseng CW, Lai CH, Tseng CJ, Lin SE, Wang CS, Huang KJ, Chou HH, Ma YY, Hsueh S, Eng HL, Fan HA. Retrograde lymphatic spread: a likely route for metastatic ovarian cancers of gastrointestinal origin. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66:372-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zabaleta J, Aguinagalde B, Fuentes MG, Bazterargui N, Izquierdo JM, Hernández CJ, Enriquez-Navascués JM, Emparanza JI. Survival after lung metastasectomy for colorectal cancer: importance of previous liver metastasis as a prognostic factor. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:786-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR. Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:8-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1491] [Cited by in RCA: 1872] [Article Influence: 62.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |