Published online Jan 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i2.496

Peer-review started: September 24, 2020

First decision: October 27, 2020

Revised: November 8, 2020

Accepted: November 29, 2020

Article in press: November 29, 2020

Published online: January 16, 2021

Processing time: 101 Days and 19.4 Hours

Intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt (IPSVS) is a rare hepatic disease with different clinical manifestations. Most IPSVS patients with mild shunts are asymptomatic, while the patients with severe shunts present complications such as hepatic encephalopathy. For patients with portal hypertension accompanied by intrahepatic shunt, portal hypertension may lead to hemodynamic changes that may result in exacerbated portal shunt and increased shunt flow.

A 57-year-old man, with the medical history of chronic hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis, was admitted to our hospital with abnormal behavior for 10 mo. He had received the esophageal varices ligation and entecavir therapy 1 year ago. Comparing with former examination results, the degree of esophageal varices was significantly reduced, while the right branch of the portal vein was significantly expanded and tortuous. Meanwhile, abdominal ultrasound presented the right posterior branch of portal vein connected with the retrohepatic inferior vena cava. The imaging findings indicated the diagnosis of IPSVS and hepatic encephalopathy. Instead of radiologic interventions or surgical therapies, this patient had only accepted symptomatic treatment. No recurrence of hepatic encephalopathy was observed during 1-year follow-up.

Hemodynamic changes may exacerbate intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. The intervention or surgery should be carefully applied to patients with severe portal hypertension due to the risk of hemorrhage.

Core Tip: Intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt (IPSVS) is a rare hepatic disease. Here we have reported a case that portal hypertension exacerbated IPSVS and resulted in hepatic encephalopathy. The decreased liver stiffness and the portal hypertension expanded IPSVS and significantly increased shunt flow. Then increased shunt ratio relieved portal hypertension, but it resulted in hyperammonia and eventually precipitated hepatic encephalopathy. This case highlights hemodynamic changes may exacerbate intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Intervention or surgery should be carefully applied to patients with severe portal hypertension due to the risk of hemorrhage.

- Citation: Chang YH, Zhou XL, Jing D, Ni Z, Tang SH. Portal hypertension exacerbates intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt and further induces refractory hepatic encephalopathy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(2): 496-501

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i2/496.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i2.496

Intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt (IPSVS) is a relatively rare hepatic disease and is more frequent in patients with liver-related diseases. IPSVS shows a wide variety of clinical manifestations, from asymptomatic to fatal complications. Previous research illustrates that intrahepatic shunts are commonly presented as multiple small shunts in patients with liver cirrhosis[1], which can be asymptomatic. Herein, we have presented that portal hypertension exacerbated asymptomatic IPSVSs and induced refractory overt hepatic encephalopathy in a patient with chronic hepatitis B and cirrhosis.

A 57-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with abnormal behavior for 10 mo, accompanied with unconsciousness, dizziness, vomiting or headache.

The above symptoms started 10 mo previous and occurred once or twice per month. The abnormal behavior, vomit and unconsciousness recurred 1 d earlier and gradually improved in 7-8 h.

The patient had been diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B 3 years ago. He was admitted to our hospital for the first time with melena and was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B, decompensated liver cirrhosis and esophageal varices 1 year ago. Our patient was assessed as Child-Pugh C, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 7.87 and MELD-Na score of 12.37. Then he started entecavir therapy and received the esophageal varices ligation. He had constipation for several months.

There is not anything special in personal and family history.

Splenomegaly was noticed in physical examination, while no signs of jaundice, anemia, bloating and abdominalgia were found.

Laboratory examination indicated the increased level of blood ammonia (97 umol/L 1.35 × upper limit of normal) and decreased level of platelets (84 × 109/L 0.84 × lower limit of normal). Meanwhile, leukocytosis, hemoglobin, liver function, coagulation, alpha-fetoprotein and hepatitis B virus DNA quantification had normal results. The result of urobilinogen was positive, while other urine indices were negative. After 1-year of entecavir therapy, the Child-Pugh of our patient changed from C to B. The MELD score decreased from 7.87 to 7.85, and the MELD-Na score decreased from 12.37 to 9.64.

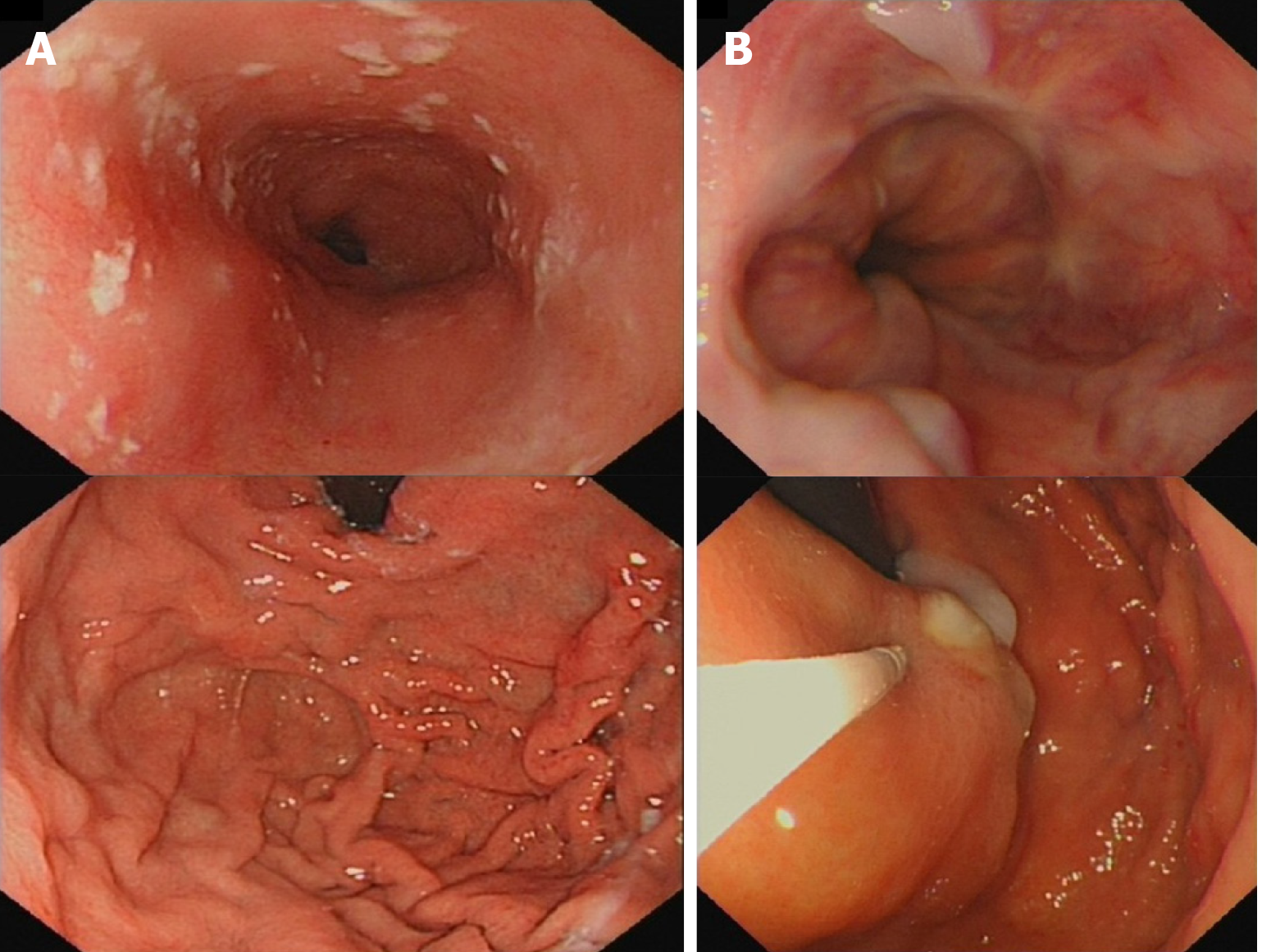

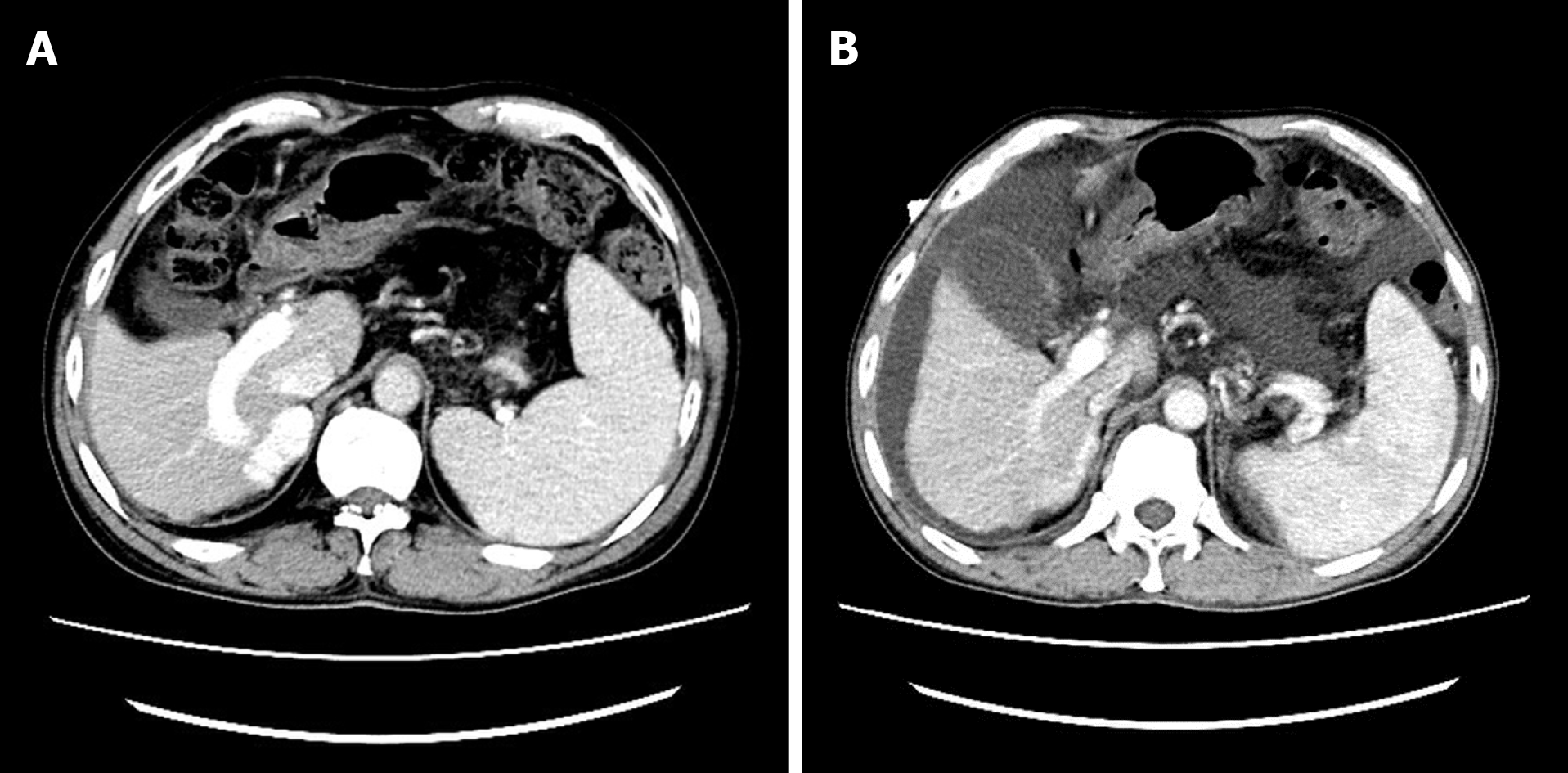

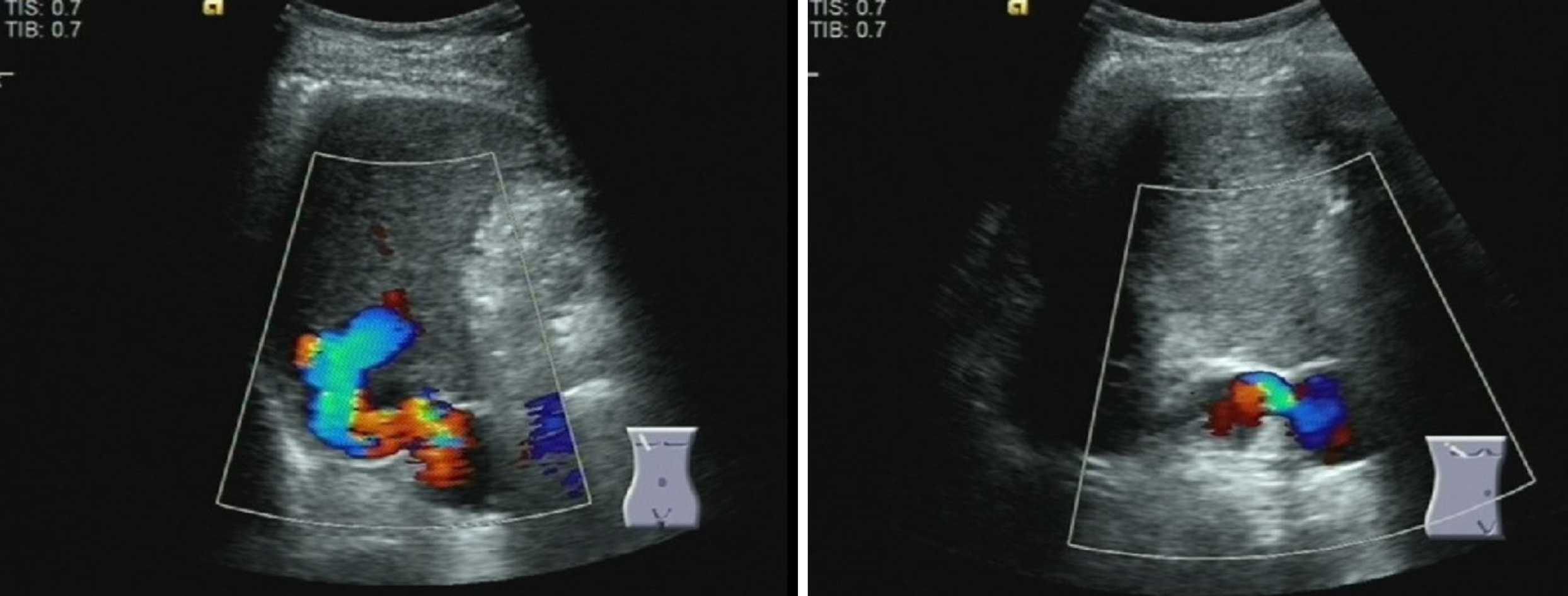

The gastroscope examination illustrated mild esophageal varices and negative red color sign (Figure 1A). Comparing with the former result, the degree of esophageal varices was significantly reduced (Figure 1B). Cranial magnetic resonance imaging indicated that there was no sign of new infarction or ischemia. Moreover, abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed cirrhosis, splenomegaly and portal hypertension with collateral circulation, while the right branch of the portal vein was expanded and tortuous (Figure 2A). The internal diameter of IPSVS was significantly enlarged from 0.3 cm to 1.3 cm when compared with previous CT results (Figure 2B). Meanwhile, abdominal ultrasound presented the right posterior branch of portal vein connected with the retrohepatic inferior vena cava (Figure 3).

These findings led us to the diagnosis of IPSVS and hepatic encephalopathy, which resulted in the abnormal behavior.

Radiologic interventions and surgical therapies are conventional treatments of IPSVS. However, considering that the patient has a history of esophageal varices, shunt-occlusion therapy may increase the risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Therefore, our patient did not receive radiologic interventions or surgical therapies and only accepted symptomatic treatment for hepatic encephalopathy. This patient was treated with a high fiber diet, branched chain amino acid, lactulose (10 mL tid oral) and rifaximin (0.2 g bid oral) combination therapy for 2 wk.

Hepatic encephalopathy did not occur after treatment, while the level of blood ammonia returned to normal and other laboratory indicators had no significant changes. No recurrence of hepatic encephalopathy was observed during 1-year follow-up.

IPSVS has various phenotypes and clinical manifestations. Previous research has categorized IPSVS into four types as follows[2]: Type 1 corresponds to the right branch of the portal vein connecting with the inferior vena cava through a shunt and is commonly encountered in portal hypertension; types II and III include the shunts between the portal branch and the hepatic vein. According to the classification, the shunts between liver segments correspond to type II, while type III includes aneurysmal communication; and type IV corresponds to the unique or multiple tubular communications between the right portal branch and the inferior vena cava. As the most common type, this patient developed a type I intrahepatic shunt. Meanwhile, IPSVS can be either asymptomatic or accompanied with complications. The existence of IPSVS may aggravate impaired liver function and result in hepatic encephalopathy or hyperammonemia[3]. A former study claimed that age and shunt ratio are risk factors of the complications. Hepatic encephalopathy is likely to occur in patients with a shunt ratio over 60%. Meanwhile, the shunt will likely remain asymptomatic in patients with a shunt ratio less than 30%[4]. For older patients, an increased risk of encephalopathy is attributed to a decreased tolerance of the brain to toxic metabolites.

In consideration of asymptomatic IPSVS, clinical examinations for intrahepatic communications are not only important for the diagnosis, but also significant for the prevention and treatment. For patients with IPSVS, ultrasound and CT are invariably required for the diagnosis of intrahepatic shunt. Meanwhile, color doppler ultrasound is important to recognize asymptomatic IPSVS, which may be misdiagnosed as hypervascular lesions on CT or sonography[4]. Moreover, the measurement of the shunt ratio by color doppler ultrasound is useful to determine the therapeutic options[5]. Although the ultrasound and CT have increased the detection rate of intrahepatic shunt, IPSVS is still a relatively rare disorder. There are only 0.0235% adults who were found with spontaneous IPSVS by color doppler ultrasound[6].

For IPSVS patients, an increased shunt ratio may induce complications. As for this patient, the brain had adapted to the small amount of toxic blood ammonia brought by the intrahepatic shunt at the beginning. IPSVS was asymptomatic before medical treatment. Then our patient received esophageal varices ligation and antiviral treatment. According to previous studies, entecavir antiviral therapy reduced liver stiffness in patients with chronic hepatitis B[7,8]. Meanwhile, the esophageal varices ligation could only treat gastrointestinal hemorrhage but not relieve portal hypertension. In consideration of the decreased liver stiffness, the portal hypertension expanded the shunt channel leading to the significant increased shunt ratio. Then increased intrahepatic shunt relieved the portal hypertension. However, the significantly increased shunt flow broke the brain’s tolerance to toxic insult, leading to the elevated risk of complications such as hepatic encephalopathy. Moreover, constipation provided the toxic blood ammonia and eventually precipitated hepatic encephalopathy. Therefore, portal hypertension and reduction of liver stiffness were the reasons of aggravated IPSVS and hepatic encephalopathy.

It is believed that radiological or surgical therapies, such as occlusion, reverse symptoms and prevent long-term complications[9]. Radiologic interventions are preferred therapies for IPSVS, and surgery is reserved for patients who are not suitable for radiologic intervention therapy or require liver transplantation. The endovascular treatment is recommended for patients presenting with symptomatic IPSVS[10,11]. However, for patients with severe portal hypertension, occlusion may lead to an increased risk of esophageal varices and hemorrhage. Considering that our patient had portal hypertension and the history of esophageal varices hemorrhage, symptomatic treatment for hepatic encephalopathy[12] was the optimal therapy for him.

In conclusion, hemodynamic changes may exacerbate intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and make it more complicated. Portal hypertension can increase shunt flow and break the brain’s tolerance to toxic substances, leading to complications such as hepatic encephalopathy. For patients with liver cirrhosis and IPSVS, continuous monitoring of intrahepatic shunt is necessary for the prevention of hepatic encephalopathy and other complications. Surgical or radiological occlusions, while effective for IPSVS, may pose challenges to management of portal hypertension. The risk of portal hypertension and hemorrhage should be fully considered before occlusion, especially for patients with severe portal hypertension.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Higuera-de la Tijera F S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Sheth N, Sabbah N, Contractor S. Spontaneous Intrahepatic Portal Venous Shunt: Presentation and Endovascular Treatment. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2016;50:349-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Senocak E, Oğuz B, Edgüer T, Cila A. Congenital intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with variant inferior right hepatic vein. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2008;14:97-99. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Remer EM, Motta-Ramirez GA, Henderson JM. Imaging findings in incidental intrahepatic portal venous shunts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:W162-W167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Prabhakar N, Vyas S, Taneja S, Khandelwal N. Intrahepatic aneurysmal portohepatic venous shunt: what should be done? Ann Hepatol. 2015;14:118-120. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bayona Molano MDP, Krauthamer A, Barrera JC, Luna C, Castillo P, Swersky A, Bhatia S. Congenital intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt embolization: A two-case experience. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:761-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lin ZY, Chen SC, Hsieh MY, Wang CW, Chuang WL, Wang LY. Incidence and clinical significance of spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunts detected by sonography in adults without potential cause. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, Afdhal N, Sievert W, Jacobson IM, Washington MK, Germanidis G, Flaherty JF, Aguilar Schall R, Bornstein JD, Kitrinos KM, Subramanian GM, McHutchison JG, Heathcote EJ. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013;381:468-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1228] [Cited by in RCA: 1362] [Article Influence: 113.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kong Y, Sun Y, Zhou J, Wu X, Chen Y, Piao H, Lu L, Ding H, Nan Y, Jiang W, Xu Y, Xie W, Li H, Feng B, Shi G, Chen G, Li H, Zheng H, Cheng J, Wang T, Liu H, Lv F, Shao C, Mao Y, Sun J, Chen T, Han T, Han Y, Wang L, Ou X, Zhang H, Jia J, You H. Early steep decline of liver stiffness predicts histological reversal of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with entecavir. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:576-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Papamichail M, Pizanias M, Heaton N. Congenital portosystemic venous shunt. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177:285-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Palvanov A, Marder RL, Siegel D. Asymptomatic Intrahepatic Portosystemic Venous Shunt: To Treat or Not To Treat? Int J Angiol. 2016;25:193-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Franchi-Abella S, Gonzales E, Ackermann O, Branchereau S, Pariente D, Guérin F; International Registry of Congenital Portosystemic Shunt members. Congenital portosystemic shunts: diagnosis and treatment. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:2023-2036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Waghray A, Waghray N, Kanna S, Mullen K. Optimal treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2014;60:55-70. [PubMed] |