Published online Jan 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i2.482

Peer-review started: September 11, 2020

First decision: November 14, 2020

Revised: November 16, 2020

Accepted: November 21, 2020

Article in press: November 21, 2020

Published online: January 16, 2021

Processing time: 118 Days and 19.9 Hours

Double-hit lymphoma is a highly aggressive B-cell lymphoma that is genetically characterized by rearrangements of MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6. Lymphoma is often accompanied by atypical systemic symptoms similar to physiological changes during pregnancy and is often ignored. Herein, we describe a gravid patient with high-grade B-cell lymphoma with a MYC and BCL-2 gene rearrangement involving multiple parts of the body.

A 32-year-old female, gestational age 22+5 wk, complained of abdominal distension, chest tightness and limb weakness lasting approximately 4 wk, and ovarian tumors were found 14 d ago. Auxiliary examinations and a trimanual gynecologic examination suggested malignant ovarian tumor and frozen pelvis. Coupled with rapid progression, severe compression symptoms of hydrothorax, ascites and moderate anemia, labor was induced. Next, biopsy and imaging examinations showed high-grade B-cell lymphoma with a MYC and BCL-2 gene rearrangement involving multiple parts of the body. She was referred to the Department of Oncology and Hematology for chemotherapy. Because of multiple recurrences after complete remission, chemotherapy plans were continuously adjusted. At present, the patient remains in treatment and follow-up.

The early detection and accurate diagnosis of lymphoma during pregnancy can help expedite proper multidisciplinary treatment to delay disease progression and decrease the mortality rate.

Core Tip: To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe a patient with double-hit lymphoma during pregnancy. We should be well aware of the gynecological manifestations of lymphoma and consider it in the differential diagnosis of pelvic tumors. To avoid an unnecessary radical operation, biopsy should be considered instead of exploratory laparotomy in young women with suspected malignant tumors as well as acute onset, rapid progression and growing chylous pleural effusion containing abundant lymphocytes. The early detection and accurate diagnosis of lymphoma during pregnancy can help expedite proper multidisciplinary treatment to delay disease progression and decrease the mortality rate.

- Citation: Xie F, Zhang LH, Yue YQ, Gu LL, Wu F. Double-hit lymphoma (rearrangements of MYC, BCL-2) during pregnancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(2): 482-488

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i2/482.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i2.482

Double-hit lymphoma (DHL) is a highly aggressive B-cell lymphoma that is genetically characterized by rearrangements of MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6. This neoplasm (high-grade B-cell lymphoma with rearrangements of MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 called DHL/triple-hit lymphoma) was identified as a new subtype in the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms[1]. The incidence rate of lymphoma is approximately 1/6000, ranking fourth in malignancies during pregnancy[2]. However, DHL is relatively uncommon. Lymphoma is often accompanied by atypical systemic symptoms similar to physiological changes during pregnancy and is often ignored. Due to its invasive nature, high risks of malignancy and recurrence and the lack of accepted treatment, it is necessary to explore effective therapies for DHL. Herein, we describe a gravid patient with high-grade B-cell lymphoma with a MYC and BCL-2 gene rearrangement involving multiple parts of the body.

A 32-year-old female, gestational age 22+5 wk, presented to the department of obstetrics of our hospital complaining of abdominal distension, chest tightness and limb weakness lasting approximately 4 wk. Ovarian tumors were found 14 d ago.

Fifty-five days prior (gestational age: 14+6 wk), her ultrasound showed no mass in the bilateral adnexal area. According to the patient, her abdominal distension, chest tightness, and limb weakness began approximately 4 wk prior (gestational age: approximately 19 wk), but she did not seek treatment. Fourteen days ago, she was diagnosed with bilateral ovarian tumors in another hospital by ultrasound showing a hypoechoic mass measuring 9.2 cm × 6.7 cm on the right side of the uterus, a hypoechoic mass measuring 9.2 cm × 6.9 cm on the left side of the uterus, an anechoic mass measuring 4.3 cm × 3.6 cm beside the uterus and pelvic effusion.

The patient noted a history of gastritis for more than 10 years.

Her parents had a history of hypertension. She had no family history of malignancies.

Her face showed signs of anemia. Her chest percussion was voiced, and her abdomen was swollen. A trimanual gynecologic examination after induced labor revealed a uterus with poor mobility, irregular masses in the bilateral adnexal area with poor mobility, a rectal fossa filled with lesions and a narrow space between the intestines.

Upon admission, her laboratory results were as follows: hemoglobin 66 g/L, hematocrit 20.4%, reticulocyte 3.28%, serum albumin 35.1 g/L, free triiodothyonine 2.34 pmol/L, and free thyroxine 16.35 pmol/L. Tumor marker levels were as follows: CA125 578.50 U/mL, alpha-fetoprotein 157.84 ng/mL, carcinoembryonic antigen 0.53 ng/mL, CA199 16.13 U/mL, Cyfra21-1 2.60 ng/mL, Fer 749.58 ng/mL, β 2-microglobulin 5.56 μg/mL, neuron-specific enolase 15.84 ng/mL, CA50 7.19 U/mL, CA153 25.70 U/mL and serum lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) 1160 U/L.

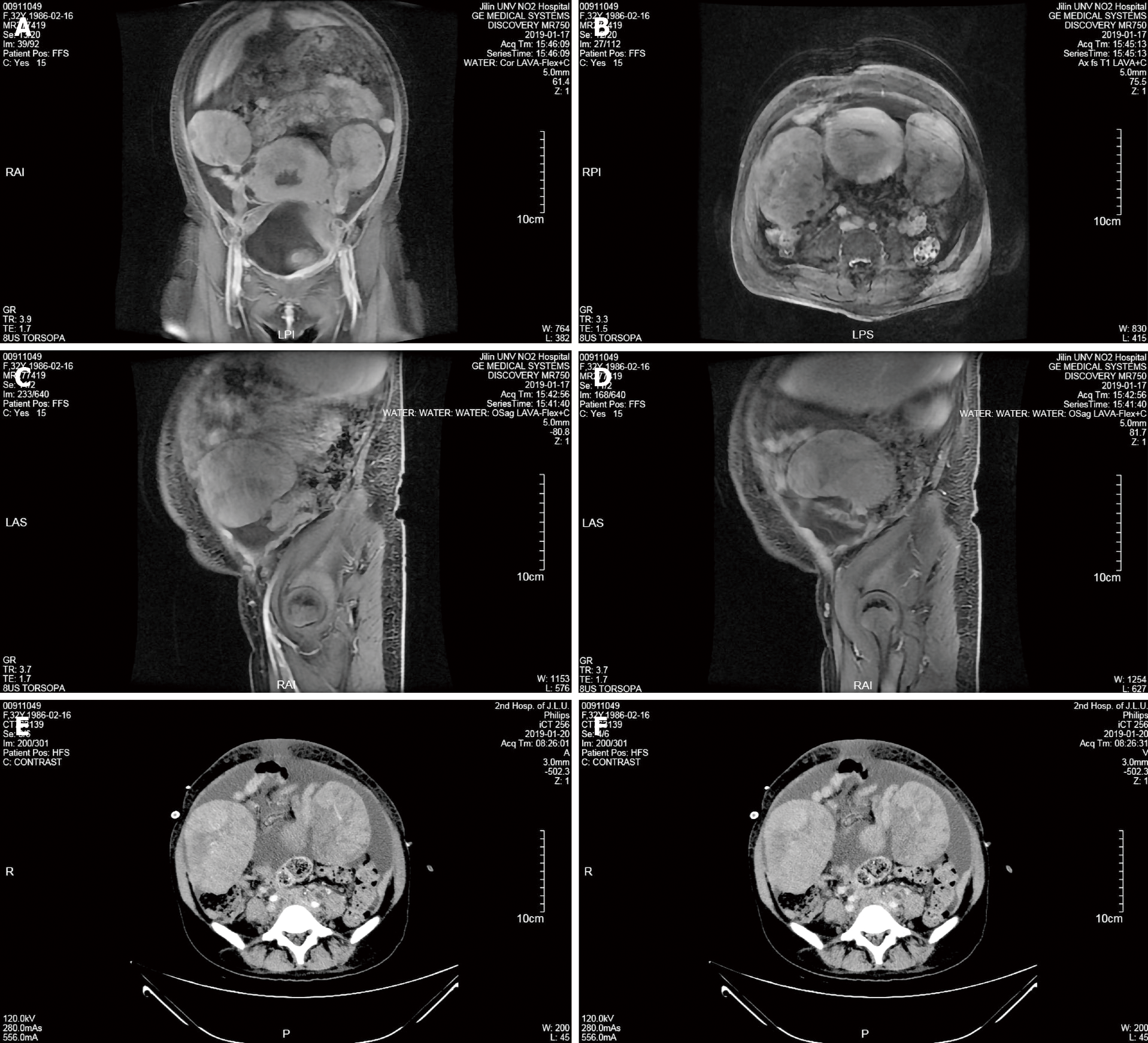

At admission, ultrasound indicated a hypoechoic mass measuring 10.7 cm × 7.8 cm in the right adnexal area and a hypoechoic mass measuring 11.2 cm × 8.2 in the left adnexa. Then, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a soft tissue mass shadow in the pelvic cavity measuring approximately 12.7 cm in the largest diameter and lesions involving the posterior wall of the bladder, adjacent bowel, cervix, upper part of the vagina and bilateral iliac vessels. The patient was diagnosed with a bilateral adnexal malignant tumor, and the pelvic mass was not excluded as metastasis (Figure 1A-D). MRI also revealed pelvic effusion, soft tissue swelling in the pelvic wall and buttock, changes in the pelvic bone and bilateral ureteral dilatation.

Ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) showed massive peritoneal and bilateral pleural effusion. Therefore, we performed ultrasound-guided puncture catheter drainage in the abdominal cavity and right thoracic cavity. Whole-abdomen CT showed bilateral pleural effusion, abdominal and pelvic effusion and malignancies of the bilateral adnexal origin that did not involve the rectum and bladder (Figure 1E and 1F). Whole-abdomen CT also revealed an irregularly shaped uterus and cervix that were not excluded as metastases, multiple soft tissue masses in the abdomen believed to be metastases, a nodular shadow in the left lateral lobe of the liver that was not excluded as metastasis, tumor involvement in the bilateral middle and lower ureters, secondary left kidney atrophy, bilateral hydronephrosis, bilateral upper ureteral dilatation and bilateral inguinal lymph nodes. After receiving the pathological results, positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) was performed and revealed multiple enlarged lymph nodes throughout the body with increased metabolism (indicative of lymphoma), some lesions that were unclearly demarcated from the uterus and adnexa, thickening of the bilateral pleural wall, pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, omentum and mesentery with increased metabolism (indicative of lymphoma infiltration), lymphoma in the right breast and increased systemic skeletal metabolism (indicative of lymphoma infiltration).

The exfoliative cytology of hydrothorax and hydroperitoneum showed many lymphocytes without cancer cells. The pathological results supported high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and the immunohistochemical staining results were as follows: LCA (+), CD20 (+), CD3 (-), CD5 (-), Cyclin D1 (-), Ki67 (positive rate 90%), CK (AE1/AE3) (-), BCL-6 (+), TdT (-), MPO (-), CgA (-), Syn (-), CD56 (-), PAX-5 (+), CD34 (-), CD10 (+), BCL-2 (+), MUM1 (-), MYC (+), CD21 (-) and CD99 (weakly +). The pathological consultation at the superior hospital resulted in a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin high-grade B-cell lymphoma with rearrangements of the MYC gene and BCL2 gene (DHL). Immunohistochemistry revealed MUM-1+, CD10+, CD38+ and LMO 2- and in situ hybridization revealed EBER-.

The final diagnosis was high-grade B-cell lymphoma with rearrangements of MYC and BCL2 (stage IV, International Prognostic Index = 4 points, age-adjusted International Prognostic Index = 3 points) (involving multiple lymph nodes, the bilateral chest wall, pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, omentum, mesentery, right breast and whole body skeleton).

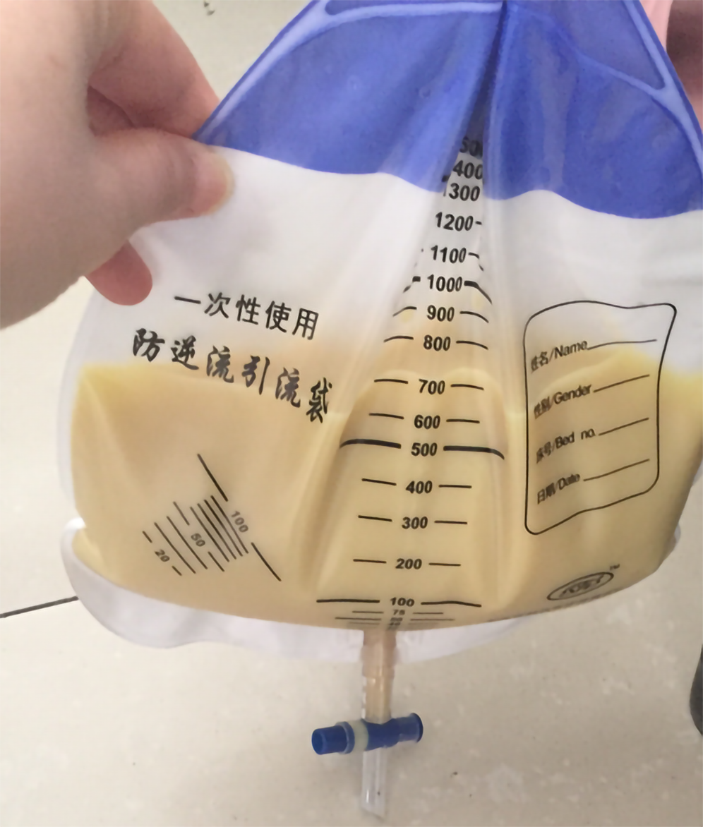

Considering the patient’s rapidly progressing condition and severe systemic symptoms, we explained the treatment options and possible risks to the patient and her husband, and then informed consent was obtained to perform rivanol-induced labor. The patient also received a blood transfusion and anti-infection, expectorant and other symptomatic treatments. After consultation, we performed ultrasound-guided puncture catheter drainage in the abdominal cavity and right thoracic cavity due to massive abdominal and pleural effusion. A large amount of yellowish chyliform fluid was drained (Figure 2). Because of severe abdominal distension and difficulty associated with enema administration, we carried out ultrasound-guided puncture biopsy of the pelvic masses rather than colonoscopy with biopsy.

The patient was immediately referred and admitted to the Department of Oncology and Hematology for chemotherapy. First, she received rituximab plus cyclo-phosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy. One course later, chemotherapy was adjusted to dose-adjusted R-EPOCH (DA-R-EPOCH) because of grade IV myelosuppression. The patient then achieved complete remission (CR) after four courses. Two months later, the disease relapsed. She received rituximab, dexamethasone, ifosfamide, cisplatin, etoposide + lenalidomide, R-DICE and the treatment of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy and achieved CR again. Two months later, the lymphoma relapsed again, and the patient received rituximab combined with a Btk inhibitor, gemcitabine + oxaliplatin, combined with azacytidine chemotherapy, oral ibrutinib and a combination of methotrexate + rituximab + gemcitabine + oxaliplatin + azacytidine.

The patient achieved CR following treatment but relapsed so rapidly that chemotherapy was continuously adjusted. At present, the patient remains in treatment and close follow-up.

The median age of onset for DHL is 51-67 years. DHL is characterized by a high level of LDH, an elevated Ki-67 index, a high-risk International Prognostic Index score and susceptibility to extranodal invasion, especially bone marrow and central nervous system (CNS) involvement[3]. The onset of lymphoma during pregnancy is insidious without typical symptoms. Lymphoma is often accompanied by systemic symptoms, such as fatigue, shortness of breath and night sweats, which is similar to physiological changes during pregnancy and is often ignored. Therefore, patients do not often visit a doctor until severe clinical symptoms appear, which may postpone the diagnosis and optimal treatment. The proportion of reproductive organs involved in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is higher during pregnancy than during nonpregnancy and commonly involves invasion of the breast followed by the ovaries and uterus[4]. Because pelvic blood flow and lymphatic drainage are abundant during pregnancy and might enhance the growth and spread of tumor cells, pregnancy may promote the occurrence and development of lymphoma. Our patient developed symptoms at 19 wk of gestation and was found to have ovarian masses reaching the frozen pelvis approximately 4 wk later. However, ultrasound showed no mass in the bilateral adnexal area at 14+6 wk of gestation. DHL progressed rapidly because pregnancy may have accelerated tumor growth and spread.

A pathological examination, including lymph node biopsy and tissue biopsy, which can be performed safely during pregnancy, is the principal means of lymphoma diagnosis. DHL can be diagnosed by fluorescent in situ hybridization[5]. Concerning the immunophenotype, B-cell markers, including CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a and CD45, are generally positive in these lymphomas, and high CD38 expression is usually observed[5]. For pregnant patients with lymphoma, it is advisable to evaluate the condition by ultrasound, MRI, a chest X-ray examination with an abdomen shield and CT or PET-CT after delivery. Bone marrow biopsy is critical to the diagnosis and staging of lymphoma and is safe during pregnancy[6]. It should be noted that when ovarian tumors are suspected to be malignant, we often perform an exploratory laparotomy. However, for young women with acute onset, rapid progression and increasing chylous pleural effusion containing abundant lymphocytes, biopsy of the lesion should be considered to avoid an unnecessary radical surgery.

As DHL is associated with a poor prognosis during pregnancy, it is necessary to consider many factors, including the stage of pregnancy, pathological type, current feasible treatment methods and patients’ willingness, when making treatment plans. Indolent NHL, with gradual progression can be monitored closely before treatment begins in the second and third trimesters[7]. For most aggressive and highly aggressive NHLs, it is crucial to begin combination chemotherapy immediately and terminate the pregnancy during early pregnancy[7]. For young women who require that their reproductive function be preserved, we should take relevant measures.

These individuals respond poorly to traditional R-CHOP alone and rapidly develop resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapy, which can result in an increased risk of relapse and a poor prognosis[5]. Recently, several centers have used DA-R-EPOCH as DHL’s preferred induction scheme[8]. A retrospective study at the MD Anderson Cancer Center showed that the DA-R-EPOCH regimen could prolong the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of DHL patients compared with the chemotherapy regimens such as R-CHOP and rituximab, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, alternating with cytarabine + methotrexate[9]. A large multicenter retrospective study showed that high-intensity induction programs such as DA-R-EPOCH, rituximab, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, alternating with cytarabine + methotrexate and cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, high-dose cytarabine could better prolong PFS in patients than R-CHOP, but there was no difference in OS[10].

Rosenthal et al[11] recommended CNS prevention for all patients with DHL. CNS prophylaxis with intravenous high-dose methotrexate should be given only after delivery[4]. Cellular therapies such as CAR-T-cell therapy can be considered in patients with refractory or repeatedly relapsed disease, preferably in the context of a clinical trial[5]. In addition, targeted agents for MYC, BCL-2 and/or BCL-6 provide new ideas for clinical research and treatment. The patient described herein had a poor response to R-CHOP therapy but was sensitive to the DA-R-EPOCH regimen and CAR-T therapy. The patient achieved CR but relapsed rapidly due to the extremely invasive nature of the tumor.

In summary, DHL is highly aggressive and malignant and responds poorly to standard R-CHOP chemotherapy. In contrast, it is sensitive to high-intensity induction chemotherapy, yet there is a high risk of recurrence after achieving CR. Therefore, it is suggested to closely monitor patients who achieve CR and adjust the chemotherapy plan when conditions change. However, more clinical trials and studies are needed to identify effective therapies.

As obstetricians and gynecologists, we should be well aware of the gynecological manifestations of lymphoma and consider it in the differential diagnosis of pelvic tumors. It is necessary to be aware of the occurrence of lymphoma when faced with unexplained abdominal distension and fatigue, a fast-growing pelvic mass, increasing hydrothorax and ascites containing many lymphocytes. Then, biopsy might be a good choice to avoid an unnecessary or excessive radical surgery. The early detection and accurate diagnosis of lymphoma during pregnancy can help expedite proper multidisciplinary treatment to delay progression and decrease the mortality rate.

We thank the family who participated in this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ristic-Medic D S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4245] [Cited by in RCA: 5426] [Article Influence: 602.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hodby K, Fields PA. Management of lymphoma in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2009;2:46-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zeng D, Desai A, Yan F, Gong T, Ye H, Ahmed M, Nomie K, Romaguera J, Champlin R, Li S, Wang M. Challenges and Opportunities for High-grade B-Cell Lymphoma With MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 Rearrangement (Double-hit Lymphoma). Am J Clin Oncol. 2019;42:304-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Avivi I, Farbstein D, Brenner B, Horowitz NA. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas in pregnancy: tackling therapeutic quandaries. Blood Rev. 2014;28:213-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Al-Juhaishi T, Mckay J, Sindel A, Yazbeck V. Perspectives on chemotherapy for the management of double-hit lymphoma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21:653-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cohen JB, Blum KA. Evaluation and management of lymphoma and leukemia in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54:556-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mahmoud HK, Samra MA, Fathy GM. Hematologic malignancies during pregnancy: A review. J Adv Res. 2016;7:589-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Friedberg JW. How I treat double-hit lymphoma. Blood. 2017;130:590-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oki Y, Noorani M, Lin P, Davis RE, Neelapu SS, Ma L, Ahmed M, Rodriguez MA, Hagemeister FB, Fowler N, Wang M, Fanale MA, Nastoupil L, Samaniego F, Lee HJ, Dabaja BS, Pinnix CC, Medeiros LJ, Nieto Y, Khouri I, Kwak LW, Turturro F, Romaguera JE, Fayad LE, Westin JR. Double hit lymphoma: the MD Anderson Cancer Center clinical experience. Br J Haematol. 2014;166:891-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Petrich AM, Gandhi M, Jovanovic B, Castillo JJ, Rajguru S, Yang DT, Shah KA, Whyman JD, Lansigan F, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Lee LX, Barta SK, Melinamani S, Karmali R, Adeimy C, Smith S, Dalal N, Nabhan C, Peace D, Vose J, Evens AM, Shah N, Fenske TS, Zelenetz AD, Landsburg DJ, Howlett C, Mato A, Jaglal M, Chavez JC, Tsai JP, Reddy N, Li S, Handler C, Flowers CR, Cohen JB, Blum KA, Song K, Sun HL, Press O, Cassaday R, Jaso J, Medeiros LJ, Sohani AR, Abramson JS. Impact of induction regimen and stem cell transplantation on outcomes in double-hit lymphoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Blood. 2014;124:2354-2361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rosenthal A, Younes A. High grade B-cell lymphoma with rearrangements of MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6: Double hit and triple hit lymphomas and double expressing lymphoma. Blood Rev. 2017;31:37-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |