Published online Jan 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i2.422

Peer-review started: August 4, 2020

First decision: November 14, 2020

Revised: November 18, 2020

Accepted: November 29, 2020

Article in press: November 29, 2020

Published online: January 16, 2021

Processing time: 154 Days and 12.3 Hours

Posterior scleritis is one of the most easily missed and misdiagnosed diseases in ophthalmology. In this case we treated a patient with intravitreal dexamethasone implant that has not been extensively studied before.

A 40-year-old female patient who had anxiety, palpitation, and insomnia presented with eye pain and decreased vision in the left eye. An eye examination indicated that her visual acuity (VA) was 40/100. Her left eye presented conjunctival edema, mild exophthalmos, clear cornea, KP(-), and clear aqueous humor. In the fundus, there was a cinerous retinal protuberance. Ultrasonography showed “T-sign” and no systemic association was detected in laboratory examination. One month after injection of dexamethasone implant, the patient exhibited VA of 20/20, fundus serous retinal detachment disappeared, and intraocular pressure of both eyes was at the normal level.

Intravitreal injection of dexamethasone implant may be a safe and effective treatment for patients with idiopathic posterior scleritis.

Core Tip: We describe a case of using intravitreal dexamethasone implant to treat a patient with idiopathic posterior scleritis.

- Citation: Zhao YJ, Zou YL, Lu Y, Tu MJ, You ZP. Intravitreal dexamethasone implant — a new treatment for idiopathic posterior scleritis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(2): 422-428

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i2/422.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i2.422

Posterior scleritis refers to inflammation of the sclera at the posterior to equator or around the optic nerve. It is one of the most easily misdiagnosed and most difficult to treat diseases in ophthalmology[1]. Due to the variety of clinical manifestations, posterior scleritis often leads to misdiagnosis. When the disease is not accompanied by anterior scleritis and no obvious sign performed in the outer eye, missed diagnosis is most likely to happen in the end. After examining some removed eyeballs, it is not uncommon to find eyeballs with primary posterior scleritis or retrogressive anterior scleritis, which indicates the clinical concealment of posterior scleritis[2]. Statistical data show that the incidence of posterior scleritis in females accounts for 71.1% of all cases. The average age is 45.9 ± 16.8 years old. In around 40% of the cases, it is associated with other systemic diseases[3]. In addition to the anterior scleritis, most of the signs are fundus changes, such as circumscribed fundus mass[4], edema of the optic disc, cystoid macular edema, exudative retinal detachment[5], optic neuritis, or retrobulbar optic neuritis[6]. In the past, patients take systemic glucocorticoid for a long time, which usually causes many side effects, such as centripetal obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, peptic ulcer, osteoporosis, infection, mental disorders, and so on[7].

This case report aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of intravitreal slow delivery of 0.7 mg dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex; Allergan Inc., Irvine, CA, United States) for idiopathic posterior scleritis.

A 40-year-old female patient sought treatment at our department because of eye pain and decreased vision in the left eye.

The patient reported pain and decreased vision of the left eye with no obvious cause 1 wk ago, with pain of the ipsilateral head and double eyelid swelling. Therefore, she visited our hospital. Since the onset of the disease, her spirit, appetite, sleep, and urine were normal.

The patient’s medical history was not remarkable, and there were no symptoms to indicate connective tissue disorder.

The patient had no family history of ocular diseases.

The examination showed that her visual acuity was 40/100 in the left eye and 100/100 in the right eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior chamber revealed clear cornea, KP(-), and clear aqueous humor. The pupillary reflex and the eye movements were normal in both eyes. No systematic deficits were noted on physical examination.

The patient’s leukocyte count was 6.06 × 109/L [normal range, (3.5-9.5) × 109/L], lymphocyte count was 1.16 × 109/L [normal range, (1.5-4) × 109/L], serum complement C3 was 0.779 g/L [normal (0.9-1.8) g/L], and the immune function test showed that her immunoglobulins were within the normal level.

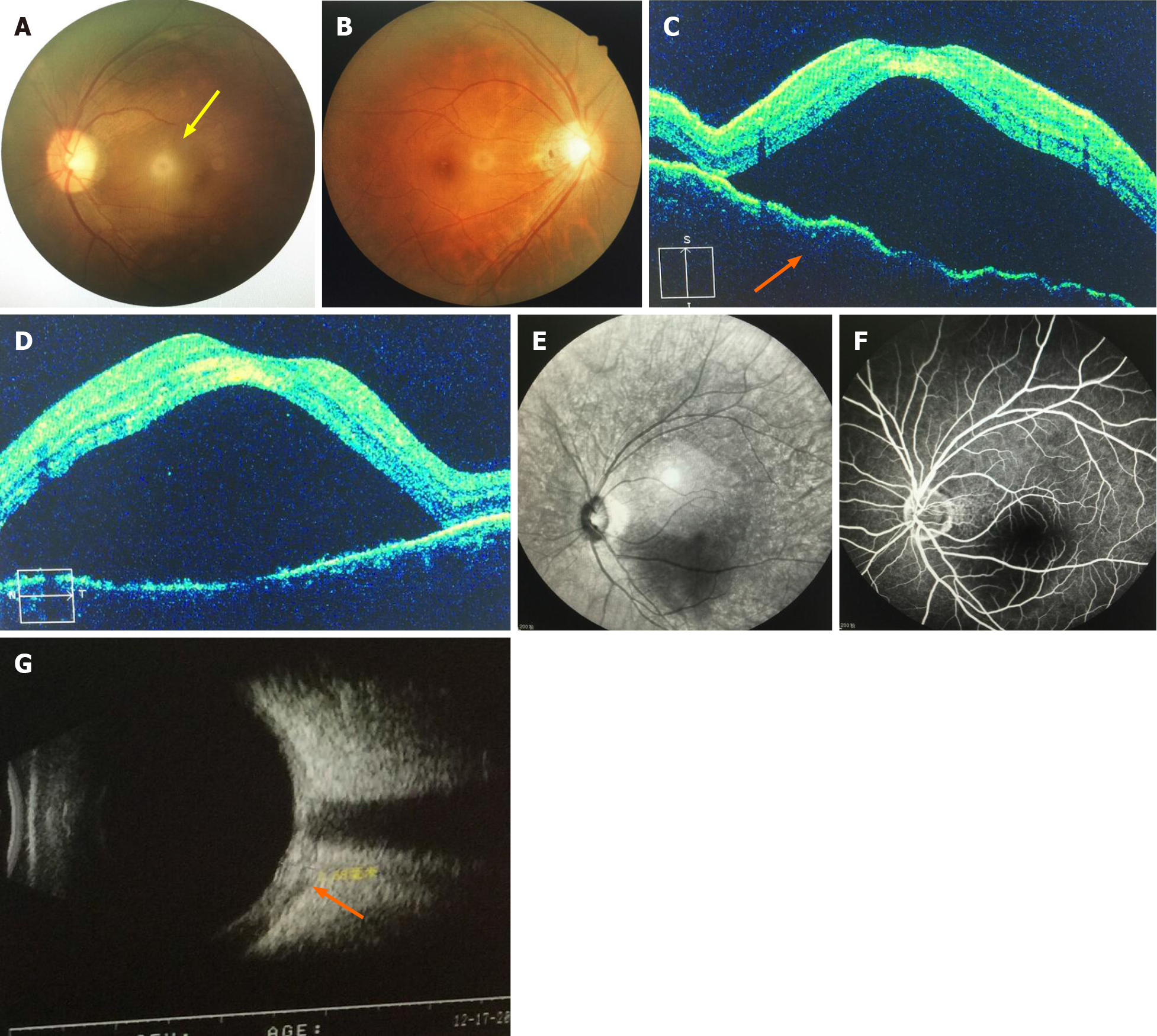

Ocular fundus images of the left eye showed that there was a cinerous protuberance of the retina in close proximity to the optic disc and the macula (Figure 1A). In her right eye, the fundus examination did not reveal any pathological findings (Figure 1B). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of her left eye showed retinal edema and choroidal folds, and at the periphery of the macular, there was serous retinal detachment (Figure 1C and D). Then, we carried out fundus fluorescein angiography. The fluorescein angiography of the left eye (red light free image) showed that there was a dark area in macula, which indicated periretinal edema (Figure 1E). In the latter stages of the angiography, there was an increased dark area at the peripheral of the macula with no leakage in choroid or retina (Figure 1F). Ultrasonography showed ‘T-sign’ with an eyeball thickness of 3.68 mm (Figure 1G). MRI examination showed left eyelid swelling and thickening of eye ring.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was idiopathic posterior scleritis.

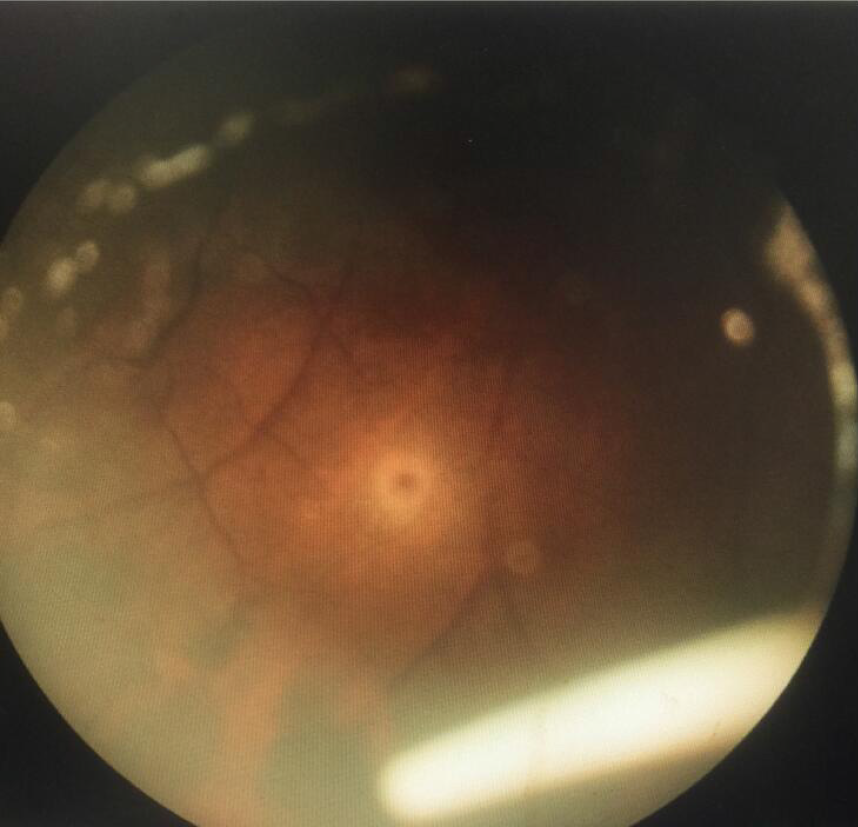

Intravitreal injection of dexamethasone implant was conducted in the left eye after relevant examinations were performed (Figure 2).

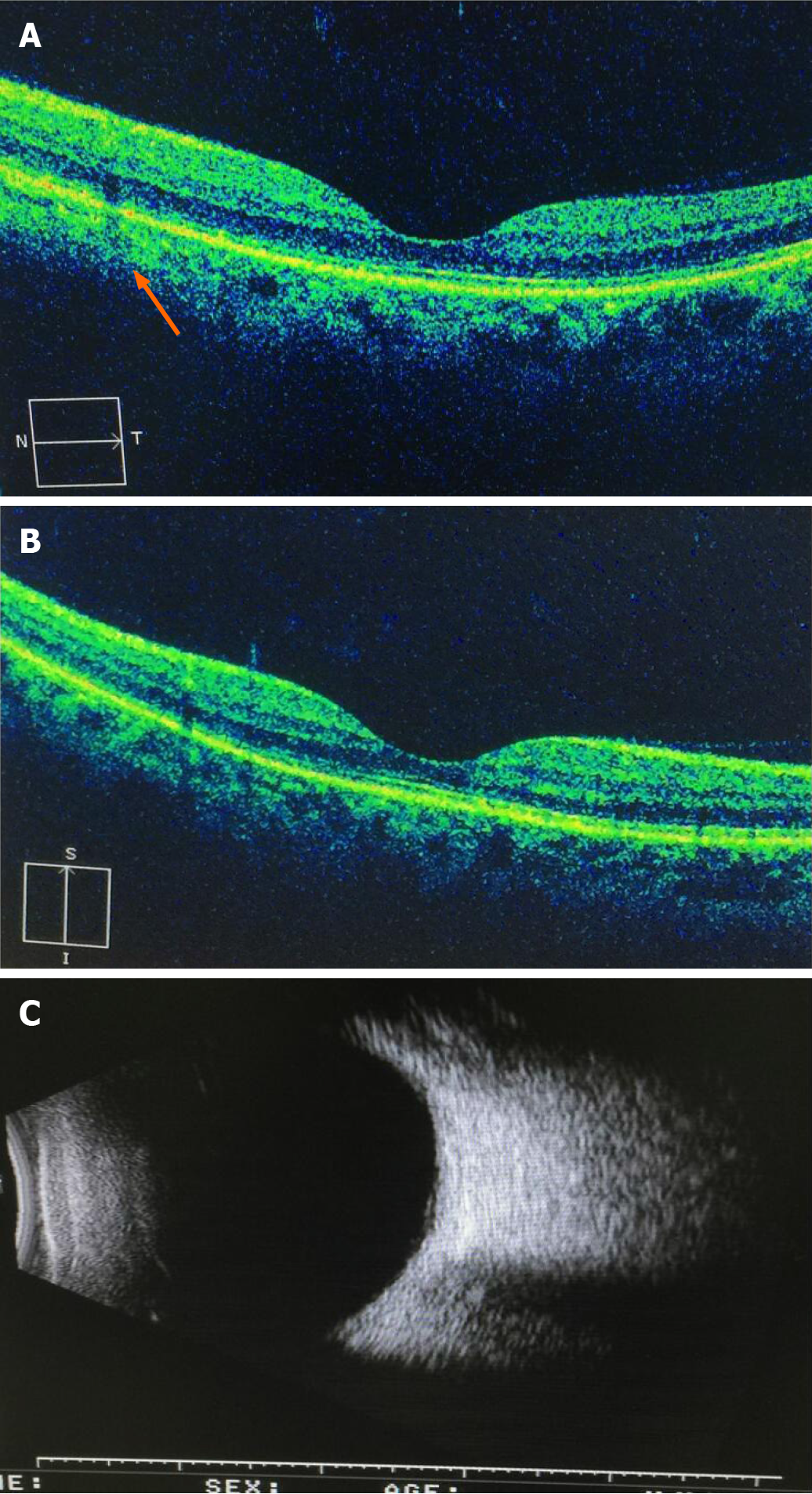

Four days after the surgery, the left eye had VA of 60/100, the fundus serous retinal detachment was relieved than before, and the thickness of fluid under the retinal became lower. Two week later, macular serous retinal detachment disappeared and retinal thickness returned to the normal level. One month later, OCT showed a normal choroidal and retina structure, but the retinal pigment epithelium and inner segment/outer segment layer in the nasal side of macula were broken off (Figure 3A and B). Three month later, the ‘T-sign’ disappeared and the thickness of the eyeball return to normal (Figure 3C). The visual acuity returned to 100/100. The intraocular pressure (IOP) of both eyes were within the normal level.

The etiology of posterior scleritis is little known, which includes exogenous and endogenous infection, autoimmune diseases, and so on. Despite extensive investigation and multidisciplinary approach which included consultation from a rheumatologist and physician, the cause of scleral inflammation in this case remained unknown. Diagnosis and treatment for posterior scleritis are a challeng in ophthalmology[8]. In the previous literature, systemic administration of corticosteroids and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is the mainstay treatment for non-infectious scleritis[9], although compliance and side effects such as fluid retention, centripetal obesity, hypertension, hypertension, digestive tract ulcers, greater susceptibility to infections, osteoporosis, mental abnormalities (excitement, insomnia, and mood changes)[10] preclude effective treatment. Systemic immunosuppressive therapy as a corticosteroid-sparing therapy is effective for ocular inflammatory diseases. However, immunnosuppressive agents may have significant side effects for those who are pregnant, such as mutagenic and teratogenic effects, which can cause fetal death or congenital malformation. Also it can increase the risk of malignancies.

Nowadays, intravitreal dexamethasone implant has already been used for macular edema due to non-infectious uveitis and retinal vein occlusions[11]. But it has rarely been used for posterior scleritis. In this case, as the patient had anxiety, palpitation, and insomnia, which could be caused by systemic administration of glucocorticoids, we considered to use intravitreal dexamethasone implant. Our results suggest that dexamethasone implant therapy is effective for idiopathic posterior scleritis. This might indicate that intravitreal dexamethasone implant is a good choice for those who have underlying diseases that might be caused by systemic glucocorticoids. In addition, we found that after 2 wk of dexamethasone implant injection, almost all fundus pathological changes, choroidal folds, and serous retinal detachment disappeared and visual acuity had great improvement. However, traditional systemic administration of corticosteroids needs more time to achieve the same effect. In contrast to systemic glucocorticoids, intravitreal dexamethasone implant has a shorter treating period, although pharmacodynamics of the implant has not been tested in the intravitreal space. In addition, intravitreal injection of dexamethasone implant was an effective approach to control refractory non-necrotizing sceritis for about 6 mo. Furthermore, as systemic glucocorticoids take a long time and might have poor therapeutic effect if the patient's compliance is not good, intravitreal dexamethasone implant might be a better choice for this problem. In the past, as corticosteroids are the mainstay treatment for non-infectious scleritis, the intravitreal injection of dexamethasone may be a good choice for this autoimmune disease associated scleritis and idiopathic scleritis.

There is also a general concern about the increase of IOP and cataracts, which were not found in our patient. But this patient developed subconjunctival hemorrhage after injection and the hemorrhage was absorbed 1 wk later. As there was a short period of follow-up in this case, more studies with a longer period of follow-up need to be performed to better elucidate the efficacy and safety of the treatment. We should weigh the advantages and disadvantages and choose the treatment carefully. Further studies on intravitreal dexamethasone implant injections should be performed to better evaluate those issues.

Intravitreal injection of dexamethasone implant is a safe and effective local treatment for idiopathic posterior scleritis. Potential advantages could include no exposure of the patients to the risks of systemic steroids. Also, it could avoid compliance issues of systemic administration of corticosteroids that may preclude effective treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Demonacos C S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Chapelle AC, Blaise P, Rakic JM. [Posterior scleritis]. Rev Med Liege. 2016;71:324-327. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Yang P, Ye Z, Tang J, Du L, Zhou Q, Qi J, Liang L, Wu L, Wang C, Xu M, Tian Y, Kijlstra A. Clinical Features and Complications of Scleritis in Chinese Patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26:387-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lavric A, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Majumder PD, Bansal N, Biswas J, Pavesio C, Agrawal R. Posterior Scleritis: Analysis of Epidemiology, Clinical Factors, and Risk of Recurrence in a Cohort of 114 Patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24:6-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ozkaya A, Alagoz C, Koc A, Ozkaya HM, Yazıcı AT. A case of nodular posterior scleritis mimicking choroidal mass. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2015;29:165-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kellar JZ, Taylor BT. Posterior Scleritis with Inflammatory Retinal Detachment. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16:1175-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Molina-Prat N, Doctor P, Tauber J, Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS. Clinical features and presentation of posterior scleritis: a report of 31 cases. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22:203-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Oray M, Abu Samra K, Ebrahimiadib N, Meese H, Foster CS. Long-term side effects of glucocorticoids. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:457-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 523] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bielefeld P, Saadoun D, Héron E, Abad S, Devilliers H, Deschasse C, Trad S, Sène D, Kaplanski G, Sève P. [Scleritis and systemic diseases: What should know the internist? Rev Med Interne. 2018;39:711-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stem MS, Todorich B, Faia LJ. Ocular Pharmacology for Scleritis: Review of Treatment and a Practical Perspective. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2017;33:240-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tappeiner C, Walscheid K, Heiligenhaus A. [Diagnosis and treatment of episcleritis and scleritis]. Ophthalmologe. 2016;113:797-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | He Y, Ren XJ, Hu BJ, Lam WC, Li XR. A meta-analysis of the effect of a dexamethasone intravitreal implant versus intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for diabetic macular edema. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18:121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |