Published online Jan 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i2.344

Peer-review started: October 16, 2020

First decision: October 27, 2020

Revised: October 30, 2020

Accepted: November 12, 2020

Article in press: November 12, 2020

Published online: January 16, 2021

Processing time: 83 Days and 16.3 Hours

There have been few reports on the risk factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and there were obvious differences regarding the incidence of ADRS between Wuhan and outside Wuhan in China.

To investigate the risk factors associated with ARDS in COVID-19, and compare the characteristics of ARDS between Wuhan and outside Wuhan in China.

Patients were enrolled from two medical centers in Hunan Province. A total of 197 patients with confirmed COVID-19, who had either been discharged or had died by March 15, 2020, were included in this study. We retrospectively collected the patients’ clinical data, and the factors associated with ARDS were compared by the χ² test, Fisher’s exact test, and Mann-Whitney U test. Significant variables were chosen for the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. In addition, literature in the PubMed database was reviewed, and the characteristics of ARDS, mortality, and biomarkers of COVID-19 severity were compared between Wuhan and outside Wuhan in China.

Compared with the non-ARDS group, patients in the ARDS group were significantly older, had more coexisting diseases, dyspnea, higher D-dimer, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and C-reactive protein. In univariate logistic analysis, risk factors associated with the development of ARDS included older age [odds ratio (OR) = 1.04), coexisting diseases (OR = 3.94), dyspnea (OR = 17.82), dry/moist rales (OR = 9.06), consolidative/mixed opacities (OR = 2.93), lymphocytes (OR = 0.68 for high lymphocytes compared to low lymphocytes), D-dimer (OR = 1.41), albumin (OR = 0.69 for high albumin compared to low albumin), alanine aminotransferase (OR = 1.03), aspartate aminotransferase (OR = 1.02), LDH (OR = 1.02), C-reactive protein (OR = 1.04) and procalcitonin (OR = 17.01). In logistic multivariate analysis, dyspnea (adjusted OR = 27.10), dry/moist rales (adjusted OR = 9.46), and higher LDH (adjusted OR = 1.02) were independent risk factors. The literature review showed that patients in Wuhan had a higher incidence of ARDS, higher mortality rate, and higher levels of biomarkers associated with COVID-19 severity than those outside Wuhan in China.

Dyspnea, dry/moist rales and higher LDH are independent risk factors for ARDS in COVID-19. The incidence of ARDS in Wuhan seems to be overestimated compared with outside Wuhan in China.

Core Tip: Some of the risk factors associated with the incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome in coronavirus disease 2019 include older age, coexisting diseases, dyspnea, dry/moist rales, consolidative/mixed opacities, lower lymphocytes/albumin, higher D-dimer, alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin. Logistic multivariate analysis showed that dyspnea, dry/moist rales, and higher lactate dehydrogenase were three independent risk factors. The incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome in coronavirus disease 2019 was higher in Wuhan than outside Wuhan in China, which may be due to a lack of sufficient medical resources in the early period of the epidemic in Wuhan.

- Citation: Hu XS, Hu CH, Zhong P, Wen YJ, Chen XY. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19 patients outside Wuhan: A double-center retrospective cohort study of 197 cases in Hunan, China. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(2): 344-356

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i2/344.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i2.344

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by a novel coronavirus named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[1], which emerged in Wuhan, China in December 2019, and rapidly spread to every province in China. Hunan Province, with the closest geographical location to Wuhan, became the second most affected area. Almost 2 mo later, COVID-19 was identified in South Korea, Japan, Europe, and United States, and then worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), through October 15, 2020, more than 38 million people had been infected and more than 1 million people had died worldwide, and these figures are still soaring[2].

During the COVID-19 outbreak, there was an increase in the number of reports regarding its clinical characteristics, and prevention and control, but few reports on the risk factors for ARDS. These risk factors are very important in predicting if critically ill patients may rapidly progress to ARDS and even death[3]. More importantly, when reviewing the literature and analyzing our data, we found that there were obvious differences in ARDS incidence, mortality rates, and intensive care unit (ICU) admission rates between Wuhan and non-Wuhan studies in China. One article published in JAMA Internal Medicine[4] showed that the incidence of ARDS in COVID-19 was 41.80% and the mortality rate was 21.9% in Wuhan, whereas in our study, the incidence of ARDS was only 6.6%. Furthermore, we reviewed the literature and found higher ARDS and mortality rates in Wuhan studies compared to non-Wuhan studies in China. It appears that COVID-19 has different features between epidemic areas and unaffected areas.

The aim of this retrospective study was to investigate the risk factors associated with ARDS of COVID-19 outside Wuhan in China, and review the literature to determine the different features of ARDS in Wuhan and in non-Wuhan areas of China.

The first objective of this retrospective study was to identify the risk factors for ARDS in COVID-19 patients; the second objective was to compare the different characteristics of ARDS between Wuhan and non-Wuhan studies in China. Patients were enrolled from two medical centers: Changsha Public Health Treatment Center (Hunan, China) and Xiangtan Central Hospital (Hunan, China). The inclusion criteria were as follows: Inpatients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19; and available data regarding epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory findings, especially ARDS findings. The inclusion criteria for literature review were: Inpatients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 according to the diagnosis and treatment protocol for COVID-19 by China[5] or the WHO[6,7]; available data on the incidence of ARDS, and/or mortality rate, ICU admission rate, discharge rate, routine blood examination, liver function, D-dimer, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein (CRP), computed tomography (CT) findings, and treatment regimens; and publication year and language regardless of the retrospective/randomized study (but excluding case reports).

This work was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital (2020-017). Written informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of the designated hospital for the nature of retrospective analysis and the newly emerged infectious disease.

We retrospectively collected COVID-19 patient data from the two medical centers mentioned above. The first date of patient admission to hospital was January 24, 2020, and the last date of admission was February 16, 2020. The first date of discharge from hospital was February 4, 2020, and the last date of discharge was March 15, 2020. The reviewed data included the basic demographic, epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, imaging, therapy and outcome data.

In the literature review, the key word “COVID-19” was used to search relevant studies in the PubMed database from the onset of COVID-19 to April 10, 2020. Relevant studies were screened and analyzed according to the PRISMA statement guidelines 2009[8]. Two reviewers (Xing-Sheng Hu and Ping Zhong) independently reviewed the literature and the incidence of ARDS, mortality, and biomarkers of disease severity were extracted.

We used the Cochrane Handbook Version 6.0 (2019) “Assessing risk of bias in a non-randomized study”[9] to assess the risk of bias within studies, based on the following four domains: Confounding bias, selection bias, information bias, and reporting biases.

COVID-19 was diagnosed on the basis of the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Infection-Induced Pneumonia version 7 (trial)[5]. Diagnosis was confirmed based on two aspects: real-time reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay of nucleic acid from respiratory or blood specimens was positive; and high-throughput gene sequencing was highly homologous with SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory or blood specimens. The real-time reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay was performed in accordance with the protocol established by the WHO[6].

Antiviral drugs were administered to the patients with confirmed COVID-19. Arbidol was given at a dose of 200 mg every 8 h, lopinavir (400 mg)/ritonavir (100 mg) (LPV/r) orally every 12 h, interferon-alpha 5 MIU was added to 2 mL normal saline and inhaled every 12 h, and novaferon 20 μg was injected intramuscularly every 12 h. All patients received the best supportive care and symptomatic treatment, if necessary, such as supplemental oxygen, noninvasive and invasive ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, antibiotic agents, corticosteroids, gamma globulin, continuous renal replacement therapy and convalescent plasma therapy. Clinical and laboratory monitoring was carried out routinely.

ARDS was defined according to the WHO interim guidance[7]. The patients’ discharge criteria and clinical classifications were evaluated according to the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Infection-Induced Pneumonia version 7 (trial)[5].

The statistical methods used in this study were reviewed by Ya Zheng from Lanzhou University (Gansu, China). Continuous variables are expressed as medians (interquartile range, IQR) and were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test; categorical variables are expressed as a number (%) and were compared using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test. Significant variables in the univariate analysis were chosen and entered into the univariate logistic regression model and multivariate regression model (measurement data were entered as continuous variables) to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and independent risk factors, using forward logistic regression methods. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 197 patients were included in this study. The median age of the 93 male and 104 female patients was 45 years. Patients who traveled to Wuhan accounted for 33.8%, and imported cases accounted for 41.5%. The most common clinical manifestations were cough (75.6%), expectoration (38.6%), fever (65.5%), fatigue (35.5%) and dyspnea (19.8%). The most common abnormal laboratory findings were low white cell count (36.0%) and low lymphocyte count (23.9%), high D-dimer (26.4%), and CRP (53.3%), and less common factors were elevated creatine kinase (CK) (9.9%), creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) (6.2%), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (16.2%), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (12.2%), and LDH (12.7%). Common characteristic CT findings were bilateral lung involvement (82.8%), ground glass opacities (86.7%), involvement of two lobes on the left (38.6%), and involvement of three lobes on the right (35.7%). The clinical characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1.

| Demographic characteristics | All patients (n = 197) | Non-ARDS (n = 184) | ARDS (n = 13) | P value |

| Ages (yr) | 45.0 (34.0-58.5) | 42 (34-57) | 58 (48-65) | 0.010 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 93/197 (47.2%) | 85/184 (46.2%) | 8/13 (61.5%) | 0.284 |

| Female | 104/197 (52.8%) | 99/184 (53.8%) | 5/13 (38.5%) | |

| Body mass index | 23.42 (21.39-25.69) | 23.29 (21.29-25.49) | 26.03 (21.50-26.89) | 0.170 |

| Smoking | 11/171 (6.4%) | 10/159 (6.3%) | 1/12 (8.3%) | 0.5621 |

| Travelling to Wuhan | 45/133 (33.8%) | 40/125 (32.0%) | 5/8 (62.5%) | 0.167 |

| Imported cases | 76/183 (41.5%) | 73/184 (39.7%) | 3/12 (25.0%) | 0.481 |

| Cluster exposure history | 132/197 (67.0%) | 127/184 (69.0%) | 5/13 (38.5%) | 0.050 |

| Coexisting disease | ||||

| Any | 49/197 (24.9%) | 42/184 (22.8%) | 7/13 (53.8%) | 0.030 |

| Heart disease | 8/197 (4.0%) | 6/184 (3.3%) | 2/13 (15.4%) | 0.0901 |

| Hypertension | 27/197 (13.7%) | 24/184 (13.0%) | 3/13 (23.1%) | 0.549 |

| Diabetes | 13/197 (6.6%) | 12/184 (6.5%) | 1/13(7.7%) | 0.600 |

| Other | 25/197 (12.7%) | 22/184 (12.0%) | 3/13 (23.1%) | 0.464 |

| Clinical manifestations | ||||

| Fever | ||||

| 37.3–39.0 °C | 115/197 (58.4%) | 107/184 (58.2%) | 8/13 (61.5%) | 0.308 |

| > 39.0 °C | 17/197 (8.6%) | 14/184 (7.6%) | 3/13 (23.0%) | |

| Non-fever | 68/197 (34.5%) | 65/184 (35.3%) | 3/13 (23.0%) | 0.551 |

| Fever | 129/197 (65.5%) | 119/184 (64.7%) | 10/13 (76.9%) | |

| Cough | 147/197 (74.6%) | 137/184 (74.5%) | 10/13 (76.9%) | 1.000 |

| Expectoration | 76/197 (38.6%) | 71/184 (38.6%) | 7/13 (53.8%) | 0.277 |

| Dyspnea | 39/197 (19.8%) | 29/184 (15.8%) | 10/13 (58.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Diarrhea | 27/197 (13.7%) | 26/184 (14.1%) | 1/13 (7.7%) | 0.814 |

| Nausea/vomit | 17/197 (8.6%) | 16/184 (8.7%) | 1/13 (7.7%) | 1.000 |

| Fatigue | 70/197 (35.5%) | 64/184 (34.8%) | 6/13 (46.2%) | 0.597 |

| Sore throat | 18/197 (9.1%) | 18/184 (9.8%) | 0/13 (0.0%) | 0.493 |

| Headache | 19/197 (9.6%) | 18/184 (9.8%) | 1/13 (7.7%) | 1.000 |

| Muscular soreness | 15/197 (7.6%) | 14/184 (7.6%) | 1/13 (7.7%) | 1.0001 |

| Total complications | 21/197 (10.7%) | 14/184 (7.6%) | 7/13 (53.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Dry/moist rales | 11/162 (6.8%) | 8/153 (5.2%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | 0.016 |

| CT imagings | ||||

| Single lung involvement | 23/169 (13.6%) | 23/150 (%) | 0/13 (%) | 0.268 |

| Bilateral lung involvement | 140/169 (82.8%) | 127/150 | 13/13 (100.0%) | |

| Ground glass opacities | 143/165 (86.7%) | 137/145 (94.5%) | 6/9 (66.7%) | 0.0181 |

| Consolidative/mixed opacities | 11/165 (6.7%) | 8/145 (5.5%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | |

| Number of lobe involvement | ||||

| Single left lobe | 58/158 (36.7%) | 55/111 (49.5%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 0.770 |

| Double left lobe | 61/158 (38.6%) | 56/111 (50.5%) | 5/8 (62.5%) | |

| Single or double right lobe | 65/157 (41.4%) | 62/113 (54.9%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 0.558 |

| Triple right lobe | 56/157 (35.7%) | 51/113 (45.1%) | 5/8 (62.5%) | |

| Laboratory findings | P value | |||

| White cell count (× 109/L) | 4.75 (3.44-5.91) | 4.75 (3.44-5.89) | 4.51 (3.06-7.05) | 0.990 |

| < 4 | 71/197 (36.0%) | 66/184 (35.9%) | 5/13 (38.5%) | 0.293 |

| 4-10 | 122/197 (61.9%) | 115/184 (62.5%) | 7/13 (53.8%) | |

| > 10 | 4/197 (2.0%) | 3/184 (1.6%) | 1/13 (7.7%) | |

| Neutrophil (× 109/L) | 2.89 (2.16-3.72) | 2.88 (2.15-3.65) | 3.31 (2.16-5.46) | 0.260 |

| < 2 | 40/197 (20.3%) | 37/184 (20.1%) | 3/13 (23.1%) | 0.325 |

| 2-7 | 152/197 (77.2%) | 143/184 (77.7%) | 9/13 (69.2%) | |

| > 7 | 5/197 (2.5%) | 4/184 (2.2%) | 1/13 (7.7%) | |

| Lymphocyte (× 109/L) | 1.20 (0.81-1.66) | 1.21 (0.88-1.69) | 0.70 (0.60-0.94) | < 0.001 |

| < 0.8 | 47/197 (23.9%) | 38/184 (20.7%) | 9/13 (69.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 130.00 (119.00-141.00) | 130.00 (119.25-140.75) | 127.50 (103.25-148.00) | 0.511 |

| < 110 g/L | 18/197 (9.1%) | 16/184 (8.7%) | 2/13 (15.4%) | 0.756 |

| Blood platelet | 173.00 (139.00-230.00) | 178.50 (139.00-229.50) | 148.00 (91.25-225.25) | 0.174 |

| < 100, × 109/L | 12/197 (6.1%) | 10/184 (5.4%) | 2/13 (15.4%) | 0.1821 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 11.5 (10.90-12.35) | 11.55 (10.90-12.30) | 11.40 (10.60-12.75) | 0.964 |

| > 16 s | 21.1 (%) | 1/184 (0.5%) | 1/13 (7.7%) | 0.128 |

| APTT (s) | 32.20 (29.80-34.75) | 32.40 (30.20-34.57) | 29.70 (26.90-35.90) | 0.212 |

| < 22 | 3/1971.5 (%) | 2/184 (1.0%) | 1/13 (%) | 0.186 |

| CK (U/L) | 64.10 (41.97-93.87) | 63.85 (41.17-91.85) | 83.20 (47.00-187.30) | 0.195 |

| > 170 U/L | 19/192 (9.9%) | 15/182 (8.2%) | 4/10 (40.0%) | 0.010 |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 9.10 (5.90-12.05) | 8.60 (5.60-11.90) | 14.10 (10.43-30.50) | 0.005 |

| > 23 | 12/193 (6.2%) | 19/183 (10.4%) | 4/10 (40.0%) | 0.021 |

| D-dmier (mg/L) | 0.26 (0.13-0.58) | 0.26 (0.12-0.56) | 1.17 (0.26-8.57) | 0.001 |

| > 0.5 | 52/165 (31.5%) | 44/153 (28.8%) | 8/12 (66.7%) | 0.016 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 38.28 (35.35-41.08) | 38.52 (35.78-41.59) | 29.90 (27.86-34.88) | < 0.001 |

| < 35 | 38/197 (19.3%) | 26/155 (16.8%) | 9/13 (69.2%) | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 20.13 (14.12-30.29) | 19.72 (13.91-28.75) | 37.41 (23.93-78.65) | < 0.001 |

| > 40 | 32/197 (16.2%) | 26/184 (14.1%) | 6/13 (46.2%) | 0.008 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.38 (19.14-31.28) | 23.12 (18.98-30.49) | 33.24 (21.47-68.61) | 0.029 |

| > 40 | 24/197 (12.2%) | 18/184 (9.8%) | 6/13 (46.2%) | 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 10.80 (7.89-15.12) | 10.67 (7.82-14.86) | 13.26 (8.81-23.31) | 0.114 |

| > 17.1 | 40/197 (20.3%) | 36/184 (19.6%) | 4/13 (30.8%) | 0.539 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 64.10 (41.98-93.88) | 51.25 (40.39-64.65) | 46.17 (36.79-111.57) | 0.684 |

| > 133 | 6/197 (3.0%) | 4/184 (2.2%) | 2/13 (15.4%) | 0.052 |

| LDH (U/L) | 161.15 (135.80-208.88) | 157.80 (133.85-205.97) | 313.60 (183.55-352.50) | < 0.001 |

| > 250 U/L | 25/197 (12.7%) | 17/184 (9.2%) | 8/13 (61.5%) | < 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 12.79 (3.55-28.50) | 12.47 (3.49-25.52) | 45.70 (13.30-72.08) | 0.003 |

| > 10 | 10/105 (53.3%) | 96/184 (52.2%) | 9/13 (69.2%) | 0.064 |

| Procalcitonin (μg/L) | 0.08 (0.06-0.20) | 0.70 (0.05-0.18) | 0.80 (0.60-71.83) | 0.117 |

| > 0.5 | 4/187 (2.1%) | 1/175 (0.6%) | 2/12 (16.7%) | 0.0111 |

| Blood glucose (mmol/L) | 161/197 (81.7%) | 5.32 (4.73-6.66) | 6.03 (5.01-12.97) | 0.169 |

| > 7 | 31/161 (19.3%) | 28/154 (18.2%) | 3/7 (42.9%) | 0.259 |

| Treatments | ||||

| Oxygen therapy | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 4/164 (2.0%) | 0/155 (0.0%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | < 0.0011 |

| Nasal cannula | 151/164 (92.1%) | 146/155 (94.2%) | 5/9 (55.6%) | |

| Did not oxygen therapy | 9/164 (5.5%) | 9/155 (5.8%) | 0/9 (0.0%) | |

| Antiviral therapy | 161/162 (99.4%) | 153/154 (99.4%) | 8/8 (100.0%) | 1.0001 |

| Antibiotic therapy | 67/153 (43.8%) | 62/147 (42.2%) | 5/6 (83.3%) | 0.116 |

| Corticosteroid | 40/161 (24.8%) | 30/151 (19.9%) | 10/10 (100.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Convalescent plasma | 4/197 (2.0%) | 0/184 (0.0%) | 4/13 (30.8%) | < 0.0011 |

| Gamma globulin | 39/157 (24.8%) | 32/150 (21.3%) | 7/7 (100.0%) | < 0.001 |

Of the included patients, 99.4% received antiviral therapy, and the most commonly used antiviral drugs were interferon, arbidol, and LPV/r. A single antiviral drug was administered in 24.5%, two antiviral drugs in 44.3%, three antiviral drugs in 23.4% and four antiviral drugs in 3.8% of patients. And 43.8% of patients received antibiotic therapy (86.6% were treated with moxifloxacin, 10.4% with levofloxacin, 0.6% with piperacillin-tazobactam, and 0.6% with ceftriaxone), 24.8% received gamma globulin therapy, 24.8% received corticosteroid therapy, 3.6% received convalescent plasma therapy, and 2.0% received mechanical ventilation (0.5% patients received invasive mechanical ventilation) therapy.

On March 15, 2020, the incidence of ARDS was 6.6%, the ICU admission rate was 8.6%, the rate of severe disease was 11.2%, the rate of critical disease was 3.6%, and the mortality rate was 1.5% (3 patients). All remaining patients were discharged from hospital.

Compared to the non-ARDS group, patients in the ARDS group were significantly older (median 58 years vs 42 years), had more coexisting diseases (53.8% vs 22.8%), more dyspnea (58.8% vs 15.8%), dry/moist rales (33.3% vs 5.2%) and consolidative/mixed opacities on CT (33.3% vs 5.5%); higher inflammation-related indicators such as CRP (median 45.70 mg/L vs 12.47 mg/L) and PCT (16.7% vs 0.6%) (P < 0.05); higher tissue injury indicators such as CK (40.0% vs 8.2%), CK-MB (median 14.1 U/L vs 8.6 U/L), ALT (median 37.41 U/L vs 19.72 U/L), AST (median 33.24 U/L vs 23.12 U/L), LDH (median 313.60 U/L vs 157.80 U/L); higher coagulation function levels including D-dimer (median 1.17 mg/L vs 0.26 mg/L), and a lower median level of lymphocytes (median 0.70 × 109/L vs 1.20 × 109/L) and albumin (median 29.90 g/L vs 38.52 g/L) (P < 0.05). The risk factors associated with ARDS are presented in Table 1.

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that older age [odds ratio (OR) = 1.04], coexisting diseases (OR = 3.94), dyspnea (OR = 17.82), dry/moist rales (OR = 9.06), consolidative/mixed opacities (OR = 2.93), lymphocytes (OR = 0.68 for high lymphocytes compared to low lymphocytes), CK (OR = 2.02), D-dimer (OR = 1.41), albumin (OR = 0.69 for high albumin compared to low albumin), ALT (OR = 1.03), AST (OR = 1.02), LDH (OR = 1.02), CRP (OR = 1.04) and PCT (OR = 17.01) were all risk factors for ARDS (P < 0.05) (measurement data were entered as continuous variables). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed only three significant independent risk factors: dyspnea (adjusted OR = 27.10), dry/moist rales (adjusted OR = 9.46) and higher LDH (adjusted OR = 1.02) (P < 0.05). The logistic regression analysis results are presented in Table 2.

| Logistic univariate regression | ||

| Variables | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Ages | 1.05 (1.00-1.09) | 0.017 |

| Dyspnea | 17.82 (4.62-68.71) | < 0.001 |

| Dry/moist rales | 9.06 (1.91-43.04) | 0.006 |

| Consolidative/mixed opacities | 2.93 (1.34-6.38) | 0.007 |

| Lymphocyte | 0.68 (0.01-0.43) | 0.004 |

| Creatine kinase | 8.00 (2.02-31.72) | 0.003 |

| Creatine kinase-MB | / | 0.255 |

| D-dmier | 1.41 (1.12-1.78) | 0.004 |

| Albumin | 0.69 (0.59-0.82) | < 0.001 |

| Alanine amino-transferase | 1.03 (1.01-1.04) | 0.001 |

| Aspartate amino-transferase | 1.02 (1.00-1.03) | 0.048 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | < 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | 0.001 |

| Coexisting disease | 3.94 (1.26-12.38) | 0.019 |

| Procalcitonin | 17.10 (2.18-134.31) | 0.007 |

| Logistic multivariate regression | ||

| Variables | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Dyspnea | 26.89 (1.77-407.72) | 0.018 |

| Dry/moist rales | 9.42 (1.02-87.08) | 0.048 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 1.02 (1.00-1.03) | 0.014 |

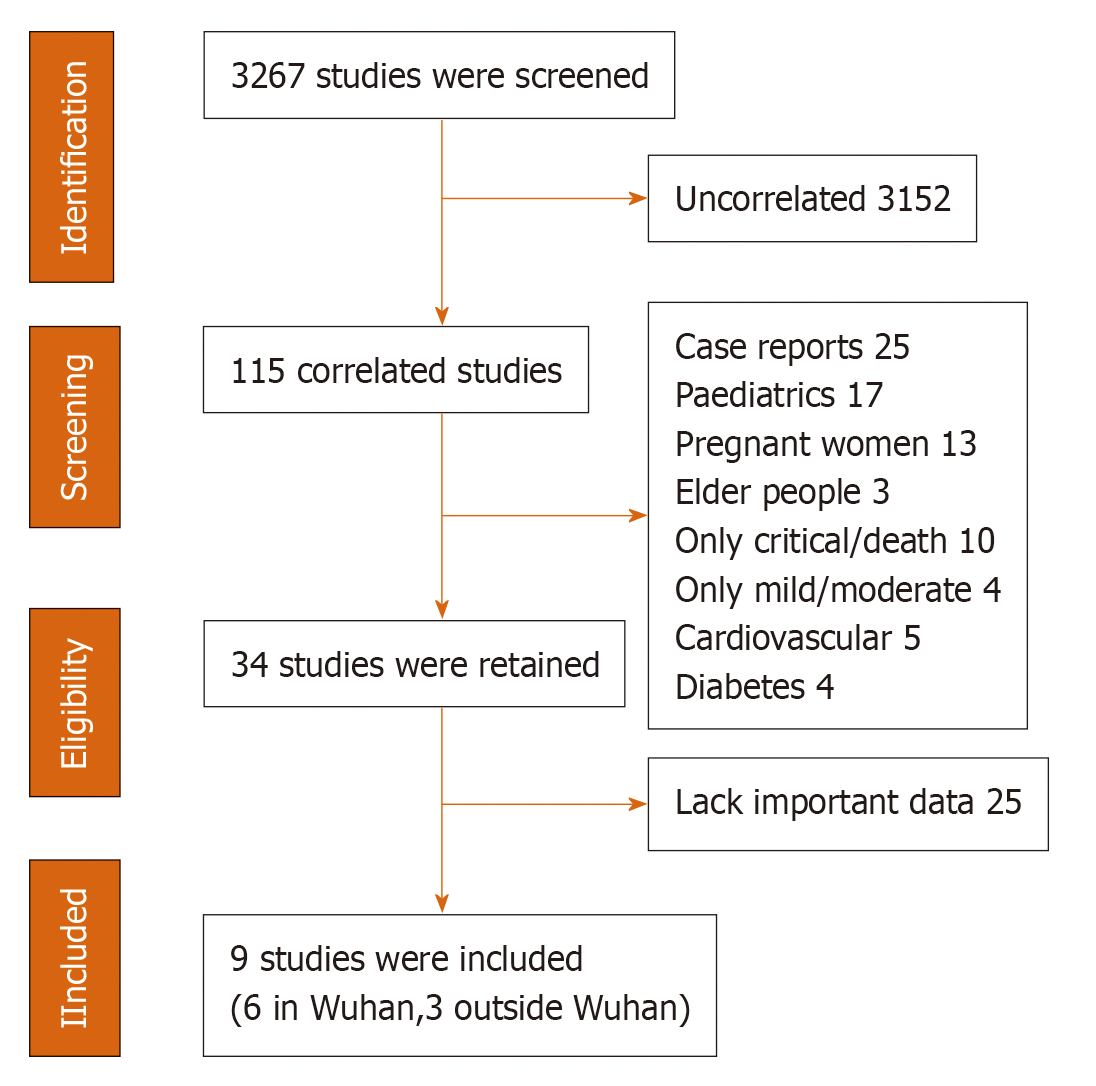

We screened 3267 reports, and 9 conformed to our inclusion criteria (6 reports in Wuhan and 3 reports outside Wuhan in China); all of them were retrospective studies. The flow chart is shown in Figure 1 and individual studies are shown in Tables 3 and 4. After assessing the studies’ bias using the Cochrane Handbook, we found that six studies of Wuhan had confounding bias, and the final follow-up date was earlier than studies outside Wuhan. At the beginning of the epidemic, the disease prevention and control and medical resources were not sufficient, which may lead to higher rates of severe disease and mortality[10]. The selection bias in Wuhan and outside Wuhan’ studies were similar; the proportions of patients still in the hospital were 23.5% and 21.3%, respectively. The information bias were also similar; two studies (Chen et al[11] and Cao et al[12]) in Wuhan and one study (Yang et al[13]) outside Wuhan did not report ARDS definition. None of the studies had obvious report bias.

| Ref. (n) | Final follow-up date | ARDS rate (%) | ICU rate (%) | Death rate (%) | Still in hospital (%) | Median age (yr) | Dyspnea (%) | WBC (4-10 × | Lymphocyte (0.8-4 × 109/L) median, elevated rate | ALT (0-40 U/L) median, elevated rate |

| Chen et al[11], (99) | 25 January | 17 | 32 | 11 | 56 | 56 | 31 | 7.5, 24% | 0.9, 35% (< 1.1) | 39, 28% (> 50) |

| Huang et al[19], (41) | 22 January | 29 | 32 | 15 | 17 | 49 | 55 | 6.2, 30% | 0.8, 63% (< 1.0) | 32 / |

| Zhou et al[14], (191) | 31 January | 31 | 26 | 28.3 | 0 | 56 | / | 6.2, 21% | 1.0, 40% | 30, 31% |

| Wang et al[17], (138) | 3 February | 19.6 | 26.1 | 4.3 | 61.6 | 56 | 31.2 | 4.5, / | 0.8, 70.3% | 24 / |

| Wu et al[4], (201) | 13 February | 41.8 | 26.4 | 21.9 | 6.5 | 51 | 39.8 | 5.9, 23.4% (> 9.5) | 0.9, 64.0% (< 1.1) | 31, 21.7% (> 50) |

| Cao et al[12], (102) | 15 February | 19.6 | 17.6 | 16.7 | 0 | 54 | / | /,/ | 0.9, 3.7% (< 1.1) | 23, 24.8% |

| Total median/mean | 26.3 | 26.7 | 16.2 | 23.5 | 53.7 | 39.5 | 6.2 (5.2-6.8) | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) | 31.0 (27.0-35.5) | |

| Outside Wuhan | ||||||||||

| Guan et al[20], (1099)1 | 31 January | 3.4 | 5 | 1.4 | 93.6 | 47 | 18.7 | 4.7, 5.9% | 1.0, 83.2% (< 1.5) | /, 21.3% |

| Chen et al[16], (249) | 25 February | 3.2 | 8.8 | 0.8 | 12.8 | 51 | 7.6 | 4.7, 28.9% | 1.1, 47.4% | 23.0 / |

| Yang et al[13], (149) | 15 February | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51.0 | 45 | 1.34 | 4.6, 1.34% | 1.2, 35.6% (< 1.1) | 20, 12.1% |

| This study (197) | 15 March | 6.6 | 8.6 | 1.5 | 0 | 45 | 19.8 | 4.8, 2.0% | 1.2, 23.9% | 20, 16.2% |

| Total median/mean | 3.3 | 5.6 | 0.9 | 21.3 | 47 | 11.9 | 4.7 (4.6-4.8) | 1.2 (1.0-1.2) | 20 (20-/) | |

| Ref. (n) | AST (0-40 U/L) median, elevated rate | D-dimer (0-0.5 mg/L) median, elevated rate | LDH (0-250 U/L) median, elevated rate | CRP (0-10 mg/L) median, elevated rate | CT bilateralpneumonia (%) | Antiviral rate (%) | Antibiotic rate (%) | Corticost-eroid rate (%) | Mechanical ventilation rate (%) |

| Chen et al[11], (99) | 34, 35% | 0.9, 36% (> 1.5) | 336, 76% | 51.3, 86% (> 5) | 75 | 76 (oseltamivir)1 | 71 | 19 | 20 |

| Huang et al[19], (41) | 34, 37% | 0.5, / | 286, 73% (> 245) | / | 98 | 93 (oseltamivir) | 100 | 22 | 29 |

| Zhou et al[14], (191) | / | 0.8, 68% | 300, 67% (> 245) | / | 59 | 21 (LPV/r) | 95 | 30 | 31 |

| Wang et al[17], (138) | 31, / | 0.20, / | 261, 39.9% (> 243) | /, / | / | 89.9 (oseltamivir) | Many5 | 44.9 | 26 |

| Wu et al[4], (201) | 33, 29.8% | 23.3% (> 1.5) | 308, 98% (> 150) | 42.4, 85.6% (> 5) | 95 | 84.6 (oseltamivir)2 | 98 | 30.8 | 33 |

| Cao et al[12], (102) | /, / | 0.19, 20.8% | /, / | 24.8, 51% | 70.6 | 98.0 (oseltamivi)3 | 99 | 50 | 19.6 |

| Total median/mean | 33.5 (31.5-34.0) | 0.65 (0.27-0.87) | 300 (273-322) | 42 (25-/) | 83 | 77.1 | 92.6 | 32.8 | 26.4 |

| Outside Wuhan | |||||||||

| Guan et al[20], (1099)6 | /, 22.2% | /, 46.4% | /, 41.0% | /, 60.7% | 51.8 | 35.8 (oseltamivir) | 58 | 18.6 | 6.10 |

| Chen et al[16], (249) | 25.0, / | / | 229, / | 12.0, 50% | 81.5 | Unknown (LPV/r, arbidol) | / | 12.9 | / |

| Yang et al[13], (149) | 23, 18.2% | 0.2, 14.1% | 210, 30.2% | 7.3, 55.0% | / | 93.9 (interferon) | 23 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| This study (197) | 23, 12.2% | 0.3, 26.4% | 161, 12.7% | 12.8, 53.3% | 8.28 | 99.4 (arbidol, LPV/r)4 | 44 | 24.8 | 2.0 |

| Total median/mean | 23 (23-/) | 0.25 (0.20-/) | 210 (161-/) | 12 (7.3-/) | 72.3 | 76.4 | 41.5 | 14.9 | 3.0 |

As demonstrated in Tables 3 and 4, the total mean incidence of ARDS (26.3% vs 3.3%), ICU admission rate (26.7% vs 5.6%), and mortality rate (16.2% vs 0.9%) were higher in Wuhan, and the final follow-up date in Wuhan were earlier than those observed outside Wuhan. The laboratory findings showed that the total median white cell count (6.2 × 109/L vs 4.7 × 109/L), ALT (31 U/L vs 20 U/L), AST (33.5 U/L vs 23.0 U/L), D-dimer (0.65 mg/L vs 0.25 mg/L), LDH (300 U/L vs 210 U/L), CRP (42 mg/L vs 12 mg/L), and mean bilateral lung involvement rate (83% vs 72%) were higher in Wuhan than outside Wuhan in China. The rates of antibiotic use (92.6% vs 41.5%), corticosteroid use (32.8% vs 14.9%), and mechanical ventilation (26.8% vs 3.0%) were also higher in Wuhan than outside Wuhan in China. All the above factors indicated that the severity of disease in Wuhan exceeded that outside Wuhan in China. The most common antiviral drug used in Wuhan was oseltamivir, while interferon, arbidol, and LPV/r were more commonly used outside Wuhan in China, which indicated that more effective drugs were used outside Wuhan in the later period of the epidemic.

This study reported the clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with ARDS in COVID-19 patients. Older age and coexisting diseases increased the risk of developing ARDS, which were also factors associated with the poor prognosis of COVID-19. Previous reports have shown that they were also associated with more deaths[12,14,15] and ICU admission[16,17], and were associated with ARDS in the study by Wu et al[4]. The reason for this may be that older patients can experience a decline in lymphocyte function and excessive expression of type 2 cytokines, which leads to defects in control of the virus and prolonged proinflammatory responses[18]. A lower level of lymphocytes or albumin was associated with more severe/deceased COVID-19 patients[14,17,19] and a higher incidence of ARDS[4], which were important independent risk factors in our study. Dyspnea was the most obvious manifestation of ARDS, the proportion of COVID-19 patients with dyspnea was 18.7%-55%[19,20], and some studies have shown that dyspnea was associated with ICU admission[9,19], and ARDS[4]. In this study, dyspnea was an independent risk factor for ARDS, and increased the risk by 26.89-fold. The incidence of dry/moist rales in COVID-19 was low (6.8%), but in the ARDS group this percentage markedly increased to 33.3%, and it was also an independent risk factor, which increased the risk by 9.42-fold. More dry/moist rales and consolidative/mixed opacities in the lung indicated severe lung inflammation, and consolidative/mixed opacities were associated with ARDS. Some studies have shown that they increased the incidence of severe/critical COVID-19[21] and the mortality rate[14], and were late indicators of COVID-19[22].

Elevations in D-dimer, LDH, and CRP are very common in COVID-19, which were important factors for poor prognosis, and all of them were related to a strong inflammatory response and disease severity. A high D-dimer level indicates that the inflammatory factors have activated the coagulation system, which might cause the formation of small thromboses and ischemia in lung blood capillaries, which could block the exchange of gas and blood in the lung, trigger the occurrence of dyspnea and ARDS, and even cause disseminated intravascular coagulation. LDH is a tissue injury indicator, CRP is an inflammatory factor, and both of these factors were associated with death[4,11,14] and ICU admission[13,16,17] in the study by Wu et al[4] and with the risk of ARDS. LDH was also an important independent risk factor for ARDS in this study. Although elevated PCT is not common in COVID-19, its elevation is associated with a more serious inflammatory response.

To determine the different characteristics in the incidence of ARDS in Wuhan and outside Wuhan in China, we reviewed the literature and compared the studies. The results showed that the studies in Wuhan commonly reported a higher incidence of ARDS, a higher mortality rate and higher biomarkers of COVID-19 severity than those outside Wuhan in China, accompanied by higher D-dimer, LDH, and CRP, which indicated more serious disease. To the best of our knowledge, there are two possible reasons that a higher incidence ARDS occurred in Wuhan. (1) Due to a lack of medical workers and material resources in the early period of the epidemic, many patients did not receive timely treatment; and (2) Due to a lack of experience related to effective therapeutic drugs in the early period, there were differences in the use of antiviral drugs in Wuhan and outside Wuhan in China. One study[10] showed that from the January 22, 2020 to March 2, 2020, the mortality rates in Wuhan declined continuously, while the mortality rates outside Wuhan in China were constant over time. This resulted from an increased number (as of March 1) of health workers who were dispatched from other provinces, increased number of acute care beds (as of February 24), and construction of temporary hospitals for admission of COVID-19 patients. However, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases was high in the early period, and the number of cases declined rapidly in the later period. Therefore, it appears that the incidence of ARDS and the mortality rate in Wuhan seem to have been overestimated. As shown in Tables 3 and 4, the main drug used in the early period of the epidemic in Wuhan was oseltamivir, which is a common antiviral drug used in influenza, although other antiviral drugs were also used, such as arbidol or LPV/r, but these accounted for only a small proportion. Therefore, the administration of different antiviral drugs may result in a different prognosis. In short, the literature review showed that the incidence of ARDS in Wuhan was higher than outside Wuhan, accompanied by higher rates of mortality and severer disease. The final follow-up date of Wuhan was earlier than outside Wuhan, which was consistent with the reasons of shortage of medical resource in earlier stage of the epidemic. These findings may be helpful for medical workers and policy makers to accurately judge the state of COVID-19 and adopt earlier intervention and treatment measures.

This study had several limitations. (1) More cases and multicenter studies of ARDS in COVID-19 are required, which may reduce selection bias; (2) In a representative literature analysis of the characteristics of ARDS in Wuhan and outside Wuhan, we only screened the PubMed database; thus, more relevant databases should be included; and (3) Some patients in the reviewed studies were still in hospital at the final follow-up date, and the literature review was only performed till April 10, 2020, so the findings may not completely reflect the total ARDS or mortality rate.

We identified some risk factors for ARDS in COVID-19 dyspnea, dry/moist rales and higher LDH are the independent risk factors for ARDS in COVID-19. The ARDS incidence, mortality rate, and biomarkers of COVID-19 severity were higher in Wuhan than that outside Wuhan of China. These findings may provide references for the researchers and policy makers of COVID-19.

There were few reports on the risk factors of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and the differences in ADRS incidence between Wuhan and outside Wuhan in China.

To identify the risk factors of ARDS in COVID-19, and determine whether the incidence of ADRS in Wuhan was overestimated compared to real world research.

The first objective of this study was to identify the risk factors for ARDS in COVID-19 patients, and the second objective was to compare the different characteristics of ARDS between Wuhan and non-Wuhan studies in China.

We retrospectively collected the patients’ clinical data, and the factors associated with ARDS were compared using the χ² test, Fisher’s exact test, Mann-Whitney U test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to compute and adjust odds ratio value. The ARDS incidence, mortality rate, and biomarkers of COVID-19 severity were collected and compared between studies in and outside Wuhan after literature review.

Older age, coexisting diseases, lower lymphocytes/albumin, higher D-dimer and C-reactive protein levels all affected the incidence of ADRS, and dyspnea, dry/moist rales and higher lactate dehydrogenase level were three independent risk factors. The ARDS incidence, mortality rate, and biomarkers of COVID-19 severity were higher in Wuhan than outside Wuhan in China.

There were some risk factors associated with ARDS in COVID-19. The higher ARDS rate in Wuhan may result from the shortage of medical resources in the early stage of the epidemic. These findings may provide references for the researchers and policy makers of COVID-19.

Biomarkers of disease severity are important risk factors for ARDS in COVID-19. The incidence of the disease should be assessed comprehensively. Accurate estimation of the incidence of ARDS will be helpful to both health workers and policy makers to develop appropriate strategies for COVID-19.

We thank Ya Zheng of Lan Zhou University for reviewing statistical methods.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ferreira LPS S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, Bi Y, Ma X, Zhan F, Wang L, Hu T, Zhou H, Hu Z, Zhou W, Zhao L, Chen J, Meng Y, Wang J, Lin Y, Yuan J, Xie Z, Ma J, Liu WJ, Wang D, Xu W, Holmes EC, Gao GF, Wu G, Chen W, Shi W, Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8473] [Cited by in RCA: 7579] [Article Influence: 1515.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | World Health Organization. 2020 OCT. 15 [Cited 15 OCT. 2020]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int. |

| 3. | Goh KJ, Choong MC, Cheong EH, Kalimuddin S, Duu Wen S, Phua GC, Chan KS, Haja Mohideen S. Rapid Progression to Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Review of Current Understanding of Critical Illness from COVID-19 Infection. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2020;49:108-118. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, Zhang L, Zhou X, Du C, Zhang Y, Song J, Wang S, Chao Y, Yang Z, Xu J, Zhou X, Chen D, Xiong W, Xu L, Zhou F, Jiang J, Bai C, Zheng J, Song Y. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:934-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4960] [Cited by in RCA: 5507] [Article Influence: 1101.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Diagnosis and treatment protocol for novel coronavirus pneumonia (7rd interim edited). China NHCOTPSRO. 2020 [Cited 15 Apr. 2020]. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202003/46c9294a7dfe4cef80dc7f5912eb1989.shtml. |

| 6. | World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) technical guidance: laboratory testing for 2019-nCoV in humans. 2020 Jan. 24 [Cited 15 Apr. 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/molecular-assays-to-diagnose-covid-19-summary-table-of-available–protocols. |

| 7. | World Health Organization. 2020 Jan.12 [Cited 15 Apr. 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-332299. |

| 8. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52948] [Cited by in RCA: 46933] [Article Influence: 2933.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Julian Higgins, James Thomas, Jacqueline Chandler, Miranda Cumpston, Tianjing Li, Matthew Page, Vivian Welch. Cochrane, 2019 July [Cited 28 OCT. 2020]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v6. |

| 10. | Zhang Z, Yao W, Wang Y, Long C, Fu X. Wuhan and Hubei COVID-19 mortality analysis reveals the critical role of timely supply of medical resources. J Infect. 2020;81:147-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14869] [Cited by in RCA: 12955] [Article Influence: 2591.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Cao J, Tu WJ, Cheng W, Yu L, Liu YK, Hu X, Liu Q. Clinical Features and Short-term Outcomes of 102 Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:748-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang W, Cao Q, Qin L, Wang X, Cheng Z, Pan A, Dai J, Sun Q, Zhao F, Qu J, Yan F. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19):A multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. J Infect. 2020;80:388-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 639] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 120.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17476] [Cited by in RCA: 18169] [Article Influence: 3633.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:846-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2604] [Cited by in RCA: 3192] [Article Influence: 638.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen J, Qi T, Liu L, Ling Y, Qian Z, Li T, Li F, Xu Q, Zhang Y, Xu S, Song Z, Zeng Y, Shen Y, Shi Y, Zhu T, Lu H. Clinical progression of patients with COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. J Infect. 2020;80:e1-e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 521] [Article Influence: 104.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14113] [Cited by in RCA: 14745] [Article Influence: 2949.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Smits SL, de Lang A, van den Brand JM, Leijten LM, van IJcken WF, Eijkemans MJ, van Amerongen G, Kuiken T, Andeweg AC, Osterhaus AD, Haagmans BL. Exacerbated innate host response to SARS-CoV in aged non-human primates. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35178] [Cited by in RCA: 30045] [Article Influence: 6009.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 20. | Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19202] [Cited by in RCA: 18835] [Article Influence: 3767.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 21. | Li K, Wu J, Wu F, Guo D, Chen L, Fang Z, Li C. The Clinical and Chest CT Features Associated With Severe and Critical COVID-19 Pneumonia. Invest Radiol. 2020;55:327-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 870] [Cited by in RCA: 794] [Article Influence: 158.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, Fan Y, Zheng C. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2493] [Cited by in RCA: 2308] [Article Influence: 461.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |