Published online Jun 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4381

Peer-review started: January 28, 2021

First decision: March 25, 2021

Revised: April 1, 2021

Accepted: April 23, 2021

Article in press: April 23, 2021

Published online: June 16, 2021

Processing time: 117 Days and 20.8 Hours

Since the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China in December 2019, the overall fatality rate of severe and critical patients with COVID-19 is high and the effective therapy is limited.

In this case report, we describe a case of the successful combination of the prone position (PP) and high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) therapy in a spontaneously breathing, severe COVID-19 patient who presented with fever, fatigue and hypoxemia and was diagnosed by positive throat swab COVID-19 RNA testing. The therapy significantly improved the patient's clinical symptoms, oxygenation status, and radiological characteristics of lung injury during hospitalization, and the patient showed good tolerance and avoided intubation. Additionally, we did not find that medical staff wearing optimal airborne personal protective equipment (PPE) were infected by the new coronavirus in our institution.

We conclude that the combination of PP and HFNO could benefit spontaneously breathing, severe COVID-19 patients. The therapy does not increase risk of healthcare workers wearing optimal airborne PPE to become infected with virus particles.

Core Tip: The outcome of severe patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is poor and the effective therapy is limited. We report a case of the successful combina

- Citation: Xu DW, Li GL, Zhang JH, He F. Prone position combined with high-flow nasal oxygen could benefit spontaneously breathing, severe COVID-19 patients: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(17): 4381-4387

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i17/4381.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4381

Since the first report of cases from Wuhan, a city in Hubei Province in China, at the end of 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread quickly around the world[1]. Currently, more than one hundred and twenty million confirmed cases have been reported to date worldwide[2]. Most cases of COVID-19 infection are mild and no deaths have been reported among noncritical cases[3]. However, almost one-fifth of COVID-19 patients have been classified as severe (14%) or critical (5%), progressing rapidly to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock and/or multiple organ dysfunction or failure[3]. Moreover, the intubation rate and mortality were high among critical cases[3,4]. Here, we report a successful example of a spontaneously breathing, severe COVID-19 patient who was successfully treated with “prone position (PP) combined with high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO)” co-interventions.

The patient presented with fever and fatigue that had lasted for 5 d.

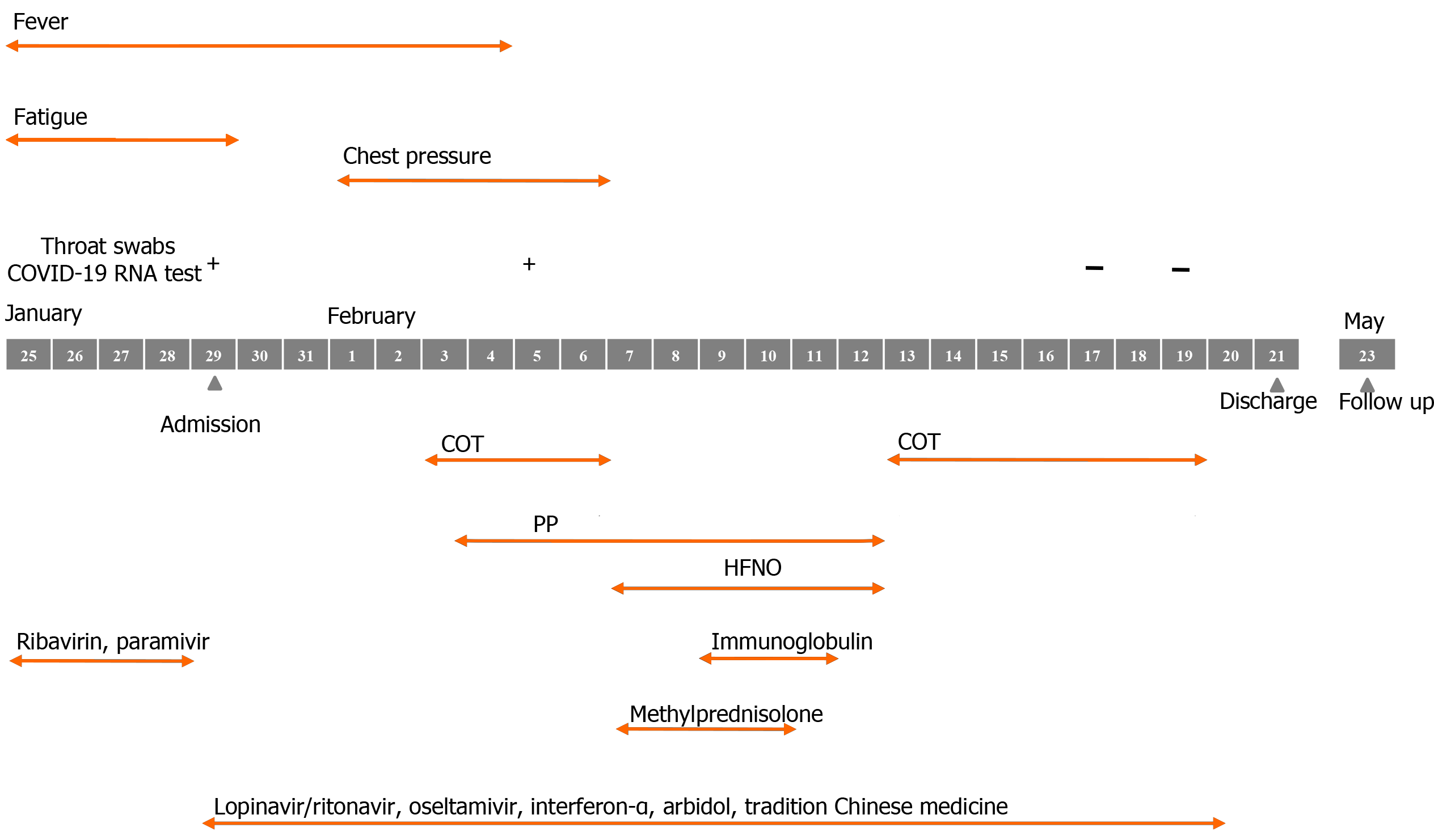

A 33-year-old healthy male presented to a local hospital reporting 5 d of fatigue and fever (from January 25 to 29, 2020). His condition did not improve after treatment (ribavirin, paramivir and tradition Chinese medicine). Then, when his throat swab COVID-19 RNA test came back positive on January 29, 2020, he was diagnosed COVID-19 and was transferred to our hospital.

The patient had no remarkable past medical history.

The patient had no markable personal and family history.

The vital signs on presentation to our hospital were temperature of 37.1 ºC, heart rate of 77 beats/min, blood pressure of 147/74 mmHg, respiratory rate of 15 beats/min, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 98% on room air. The examination of respiratory system was normal.

Laboratory data on presentation in our institution revealed a white blood cell count of 3.18 × 109/L, neutrophil ratio of 75.2%, lymphocyte ratio of 16.2%, aspartate aminotransferase of 27 U/L, alanine aminotransferase of 19 U/L, blood urea nitrogen of 4.7 mmol/L, creatine kinase of 71.1 mmol/L, C-reaction protein of 8.0 mg/L, and an arterial blood gas (ABG) of pH: 7.41, PaO2: 87.0 mmHg, and PaCO2: 38.0 mmHg on room air.

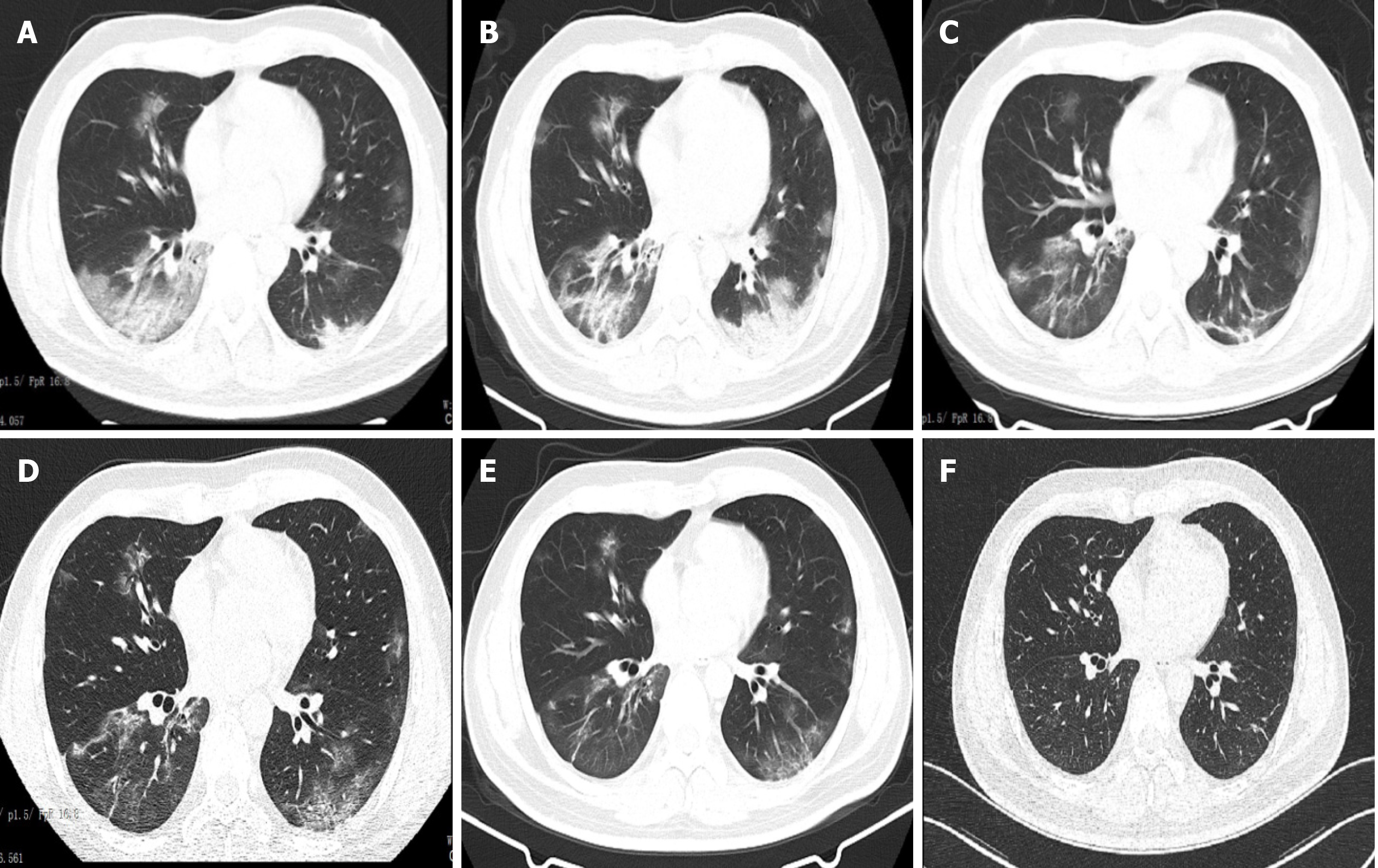

The results of the patient’s chest computed tomography (CT) scan during hospitalization are shown in the treatment section (Figure 1).

COVID-19.

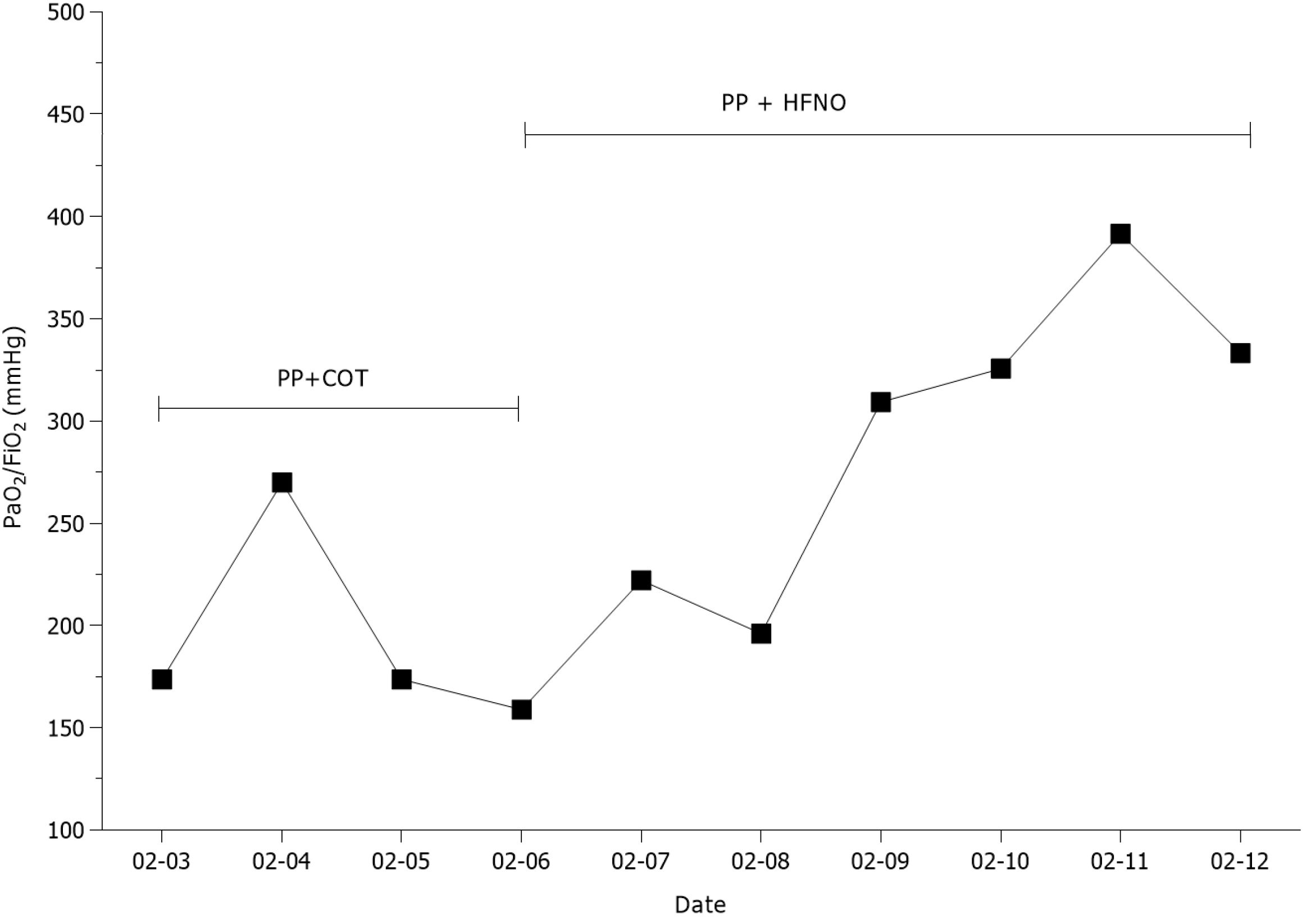

The patient received lopinavir/ritonavir, oseltamivir, interferon-α and traditional Chinese medicine after admission, according to the “Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Infection” by the National Health Commission (trial version 4). However, the patient’s condition worsened, manifesting a persistent fever (maximum temperature: 38.9 ºC), chest tightness and shortness of breath occurring at rest on hospital day (HD) 6 (February 3, 2020). The patient’s SpO2 decreased to 91% and conventional oxygen therapy (COT) was performed. An ABG analysis showed pH: 7.44, PaO2 57.3 mmHg, and PaCO2 37.7 mmHg, at a FiO2 of 0.33 (Figure 2). The chest CT revealed bilateral focal ground-glass opacity associated with consolidation in the right lower lobes (Figure 1A). At this point, PP was initiated (HFNO and a non-invasive ventilator was not available at that time) and was carried out by our staff wearing optimal airborne personal protective equipment (PPE) according to the previous study[5]. The patient was placed in the PP for 6 h per day with estazolam 1 mg administered orally daily, which he tolerated well. However, the patient’s condition did not improve after PP therapy. The ABG analysis showed pH of 7.44, PaO2 of 52.4 mmHg, and PaCO2 of 39.1 mmHg, at a FiO2 of 0.33 (Figure 2), while CT of the chest revealed consolidation in the right and left lower lobes on HD 9 (February 6, 2020) (Figure 1B). Then, the co-intervention with PP and HFNO (at a flow of 40 L/min and a FiO2 of 35%) was performed and the patient concurrently received corticosteroid and immunoglobulin therapy. The patient showed gradual improvement in clinical symptoms, oxygenation and the radiological changes of the lungs during the co-intervention (Figures 1C and 2). On HD 15 (February 12, 2020), the patient’s condition had markedly improved. ABS analysis in the supine position showed pH of 7.44, PaO2 of 70.0 mmHg, PaCO2 of 41.0 mmHg, and COT at a FiO2 of 0.21 (Figure 2). A CT scan of the chest revealed that the ground-glass opacities and consolidations were dissipating (Figure 1D). The co-intervention was completed on HD 16 (February 13, 2020). On HD 21 (February 18, 2020), the patient’s vital signs were normal. The ABG analysis showed pH of 7.45, PaO2 of 78.9 mmHg, and PaCO2 of 42.2 mmHg, on room air, while a CT scan of the chest revealed further resolution of the lesions (Figure 1E). Two throat swab COVID-19 RNA tests were negative (February 17 and 19, 2020).

The patient was discharged in good condition on HD 24 (February 21, 2020). He was found to be completely recovered at a 3-mo follow-up appointment (Figure 3) and chest CT was normal on May 23, 2020 (Figure 1F).

It is well known that COVID-19 typically affects the respiratory system of human beings and some patients will develop profound acute hypoxemic respiratory failure requiring hospitalization and oxygenation support[6]. Most patients with hypoxemia received COT or HFNO alone as initial support; however, the success rates of these treatments were low[7]. This is because the small airway cavities of these patients are blocked by a large number of mucus plugs, which leads to atelectasis and ventilation-perfusion mismatch[8]. Under these circumstances, COT or HFNO alone cannot improve the worsening oxygenation status in patients with COVID-19, which leads to higher intubation and mortality rates. In our case, the patient received COT alone after admission; however, his oxygenation deteriorated (PaO2/FiO2 of 198) and was accompanied by radiological changes of the lungs, i.e. bilateral focal ground-glass opacity and consolidation. Then, PP respiratory support was performed by our team.

PP respiratory support refers to the delivery of respiratory support with the patient lying in the PP. It reduces the ventral-dorsal transpulmonary pressure difference and dorsal lung compression, and improves lung perfusion, with resultant improvement in gas exchange[9]. Previous studies have demonstrated that early PP combined with HFNO could improve oxygenation and avoid the need for intubation in moderate ARDS patients with non-COVID-19 conditions; moreover, the PP was well tolerated in these cases[10,11]. Recently, in a retrospective study, 10 non-intubated, spontaneously breathing patients with severe COVID-19 received early awake PP combined with HFNO. The results revealed that the oxygenation of all patients was improved and none progressed to critical condition or needed endotracheal intubation[12]. It is interesting to note that although PP combined with HFNO improved the oxygenation and lung injury in radiological features of the patient in our case, the effect of PP combined with COT is not good in the early period. Despres et al[13] showed similar findings reporting on PP combined with HFNO or COT in severe COVID-19 patients. The results revealed that compared with PP combined with COT therapy, PP combined with HFNO significantly improved oxygenation and decreased the incidence of intubation. This result may be explained by the fact that, first, humidified and heated air is thought to facilitate airway secretion clearance and avoid airway desiccation and epithelial injury[14,15]. Second, high airflow rates could washout nasopharyngeal dead space and improve breathing patterns (e.g., increased minute ventilation, decreased respiratory rate), and improve oxygenation[13]. Third, HFNO create a positive end expiratory pressure effect, contributing to decreasing the work of breathing and enhance oxygenation[16]. Of note, the potential harm of the new coronavirus particle aerosol generated by HFNO could place medical staff at high risk of infection[17]. Fortunately, we did not find that medical staff wearing optimal airborne PPE were infected by the new coronavirus in our institution.

There are some limitations in our report. Our findings were derived from a single patient, and there needs to be further assessments in more patients. Also, we reported the benefits of the therapy in a spontaneously breathing patient with severe COVID-19 infection but did not evaluate the comfort of the patient. Previous study has shown that the tolerance and compliance of a patient might influence the therapy[18].

In summary, our case demonstrates that combination of PP and HFNO could benefit spontaneously breathing, severe COVID-19 patients in improving clinical symptoms, oxygenation status and radiological features of lung injury. Moreover, the therapy does not increase the risk that healthcare workers wearing optimal airborne PPE could become infected with virus particles.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Khan MKA S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Xing X, Xiang N, Wu Y, Li C, Chen Q, Li D, Liu T, Zhao J, Liu M, Tu W, Chen C, Jin L, Yang R, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang R, Liu H, Luo Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Li H, Tao Z, Yang Y, Deng Z, Liu B, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Shi G, Lam TTY, Wu JT, Gao GF, Cowling BJ, Yang B, Leung GM, Feng Z. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11224] [Cited by in RCA: 9312] [Article Influence: 1862.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). [cited 1 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. |

| 3. | Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239-1242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11409] [Cited by in RCA: 11503] [Article Influence: 2300.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bhargava A, Fukushima EA, Levine M, Zhao W, Tanveer F, Szpunar SM, Saravolatz L. Predictors for Severe COVID-19 Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1962-1968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Valter C, Christensen AM, Tollund C, Schønemann NK. Response to the prone position in spontaneously breathing patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:416-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19202] [Cited by in RCA: 18866] [Article Influence: 3773.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 7. | Tang X, Du RH, Wang R, Cao TZ, Guan LL, Yang CQ, Zhu Q, Hu M, Li XY, Li Y, Liang LR, Tong ZH, Sun B, Peng P, Shi HZ. Comparison of Hospitalized Patients With ARDS Caused by COVID-19 and H1N1. Chest. 2020;158:195-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu Q, Wang RS, Qu GQ, Wang YY, Liu P, Zhu YZ, Fei G, Ren L, Zhou YW, Liu L. Gross examination report of a COVID-19 death autopsy. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;36:21-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Scholten EL, Beitler JR, Prisk GK, Malhotra A. Treatment of ARDS With Prone Positioning. Chest. 2017;151:215-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ding L, Wang L, Ma W, He H. Efficacy and safety of early prone positioning combined with HFNC or NIV in moderate to severe ARDS: a multi-center prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 54.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Scaravilli V, Grasselli G, Castagna L, Zanella A, Isgrò S, Lucchini A, Patroniti N, Bellani G, Pesenti A. Prone positioning improves oxygenation in spontaneously breathing nonintubated patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure: A retrospective study. J Crit Care. 2015;30:1390-1394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu Q, Wang T, Qin X, Jie Y, Zha L, Lu W. Early awake prone position combined with high-flow nasal oxygen therapy in severe COVID-19: a case series. Crit Care. 2020;24:250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Despres C, Brunin Y, Berthier F, Pili-Floury S, Besch G. Prone positioning combined with high-flow nasal or conventional oxygen therapy in severe Covid-19 patients. Crit Care. 2020;24:256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee CC, Mankodi D, Shaharyar S, Ravindranathan S, Danckers M, Herscovici P, Moor M, Ferrer G. High flow nasal cannula versus conventional oxygen therapy and non-invasive ventilation in adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: A systematic review. Respir Med. 2016;121:100-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Williams R, Rankin N, Smith T, Galler D, Seakins P. Relationship between the humidity and temperature of inspired gas and the function of the airway mucosa. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1920-1929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Parke RL, McGuinness SP. Pressures delivered by nasal high flow oxygen during all phases of the respiratory cycle. Respir Care. 2013;58:1621-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lyons C, Callaghan M. The use of high-flow nasal oxygen in COVID-19. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:843-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Prasad M, Visrodia K. Should I prone non-ventilated awake patients with COVID-19? Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;Online ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |