Published online Jun 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4357

Peer-review started: January 21, 2021

First decision: February 11, 2021

Revised: March 6, 2021

Accepted: March 25, 2021

Article in press: March 25, 2021

Published online: June 16, 2021

Processing time: 124 Days and 23.7 Hours

Clostridium perfringens (C. perfringens) is an opportunistic pathogen. It can cause infections after birth, after an abortion, and in patients with diabetes, malignancy, liver cirrhosis, or an immunosuppressive state. Here, we report a patient with C. perfringens infection secondary to acute pancreatitis, with no underlying diabetes, malignancy, or liver cirrhosis.

A 62-year-old Han Chinese woman presented to the Tianjin Hospital of ITCWM Nankai Hospital on January 8, 2020 because of epigastric abdominal pain. Laboratory examination showed that urine amylase was 10403 U/L (reference: 47-458), and blood amylase was 1006 U/L (reference: < 100). Abdominal computed tomography showed pancreatic edema and peripancreatic exudation. She was diagnosed with mild acute pancreatitis and treated accordingly. She was readmitted the next day for similar symptoms. Two hours later, she went to the lavatory and urinated, and the urine color was like soy sauce. Oxygen saturation decreased to 77%, and she developed consciousness disturbance. She was admitted to the intensive care unit. After 8 h in the hospital, she had a high fever of 40 ℃, blood was drawn for culture, and 3 g of cefoperazone/sulbactam was administered. After 12 h, she had a cardiac arrest and died shortly. Blood culture confirmed a C. perfringens infection.

C. perfringens infection may be secondary to acute pancreatitis. Rapid recognition and aggressive early management are critical for the survival of patients with C. perfringens infection.

Core Tip: Clostridium perfringens (C. perfringens) is an opportunistic pathogen. This patient had a C. perfringens infection with no underlying diabetes, malignancy, or liver cirrhosis. C. perfringens infection may be secondary to acute pancreatitis and cause quick death of the patient. Rapid recognition and aggressive early management are critical for the survival of patients with C. perfringens infection.

- Citation: Li M, Li N. Clostridium perfringens bloodstream infection secondary to acute pancreatitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(17): 4357-4364

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i17/4357.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4357

Clostridial toxic shock syndrome is a life-threatening, toxin-mediated systemic illness caused by infection with either Clostridium sordellii (C. sordellii) or Clostridium perfringens (C. perfringens)[1-3]. Most cases occur post-partum or following sponta

Here, we report a patient with C. perfringens infection secondary to acute pancreatitis, with no underlying diabetes, malignancy, or liver cirrhosis.

A 62-year-old Han Chinese woman presented to the emergency room of Tianjin Hospital of ITCWM Nankai Hospital on January 8, 2020 because of epigastric abdominal pain.

The patient’s symptoms started 2 d ago without nausea, vomiting, jaundice, fever, or chill.

The patient had a history of hyperthyroidism (she had radiotherapy and the subsequent hypothyroidism was treated with long-term levothyroxine) and hyperlipemia, but no medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or malignancy. The patient had acute pancreatitis 3 mo ago and was cured by anti-pancreatitis treatment.

The patient was born in Tianjin and lived there since birth. She had no history of smoking and alcohol consumption. Her family had no history of genetic disease.

Physical examination revealed normal temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation (OS), no jaundice, dry mucous membranes, lungs clear to auscultation, abdomen soft but tender in the upper abdomen, and no rash.

Urine amylase was 10403 U/L (reference: 47-458) and blood amylase was 1006 U/L (reference: < 100). Urobilinogen and urobilirubin were negative. Total cholesterol was 6.84 mmol/L (reference: < 5.2). Low density lipoprotein was 4.54 mmol/L (reference: < 3.12).

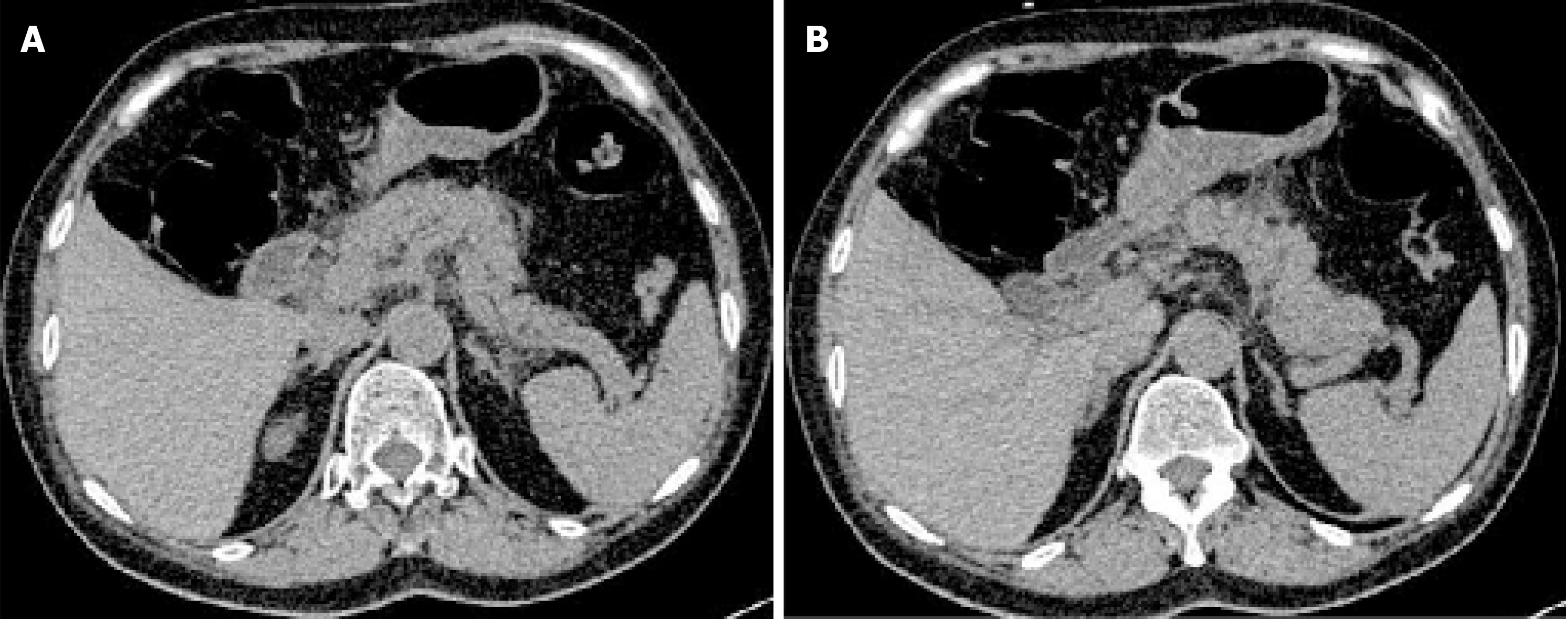

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed pancreatic edema and peripancreatic exudation but no cholecystitis or cholangiectasis (Figure 1). Abdominal ultrasound showed no cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis, cholecystitis, or cholangiectasis.

The possible diagnoses might be acute pancreatitis, acute cholecystitis, acute gastritis, acute appendicitis, and gastrointestinal perforation. Examinations were performed to rule out diagnoses. CT and abdominal ultrasound had excluded the others, and acute pancreatitis was finally confirmed, the severity of which was graded as mild[4]. The cause of acute pancreatitis might be hyperlipidemic or idiopathic.

The patient refused hospitalization and was given etimicin 300 mg/d IV for empiric antibiotic therapy, lansoprazole 30 mg/d IV for acid suppression, octreotide 0.3 g SC injection for inhibiting pancreas secretion, alprostadil 10 mg IV into Murphy's dropper for improving microcirculation of the pancreas, dezocine 5 mg IM and ketochrometritol 30 mg/d IV for analgesia, glucose sodium chloride 5%, and potassium chloride 10 mL/d IV for keeping water electrolyte balance. She left the hospital after the symptoms were relieved a little.

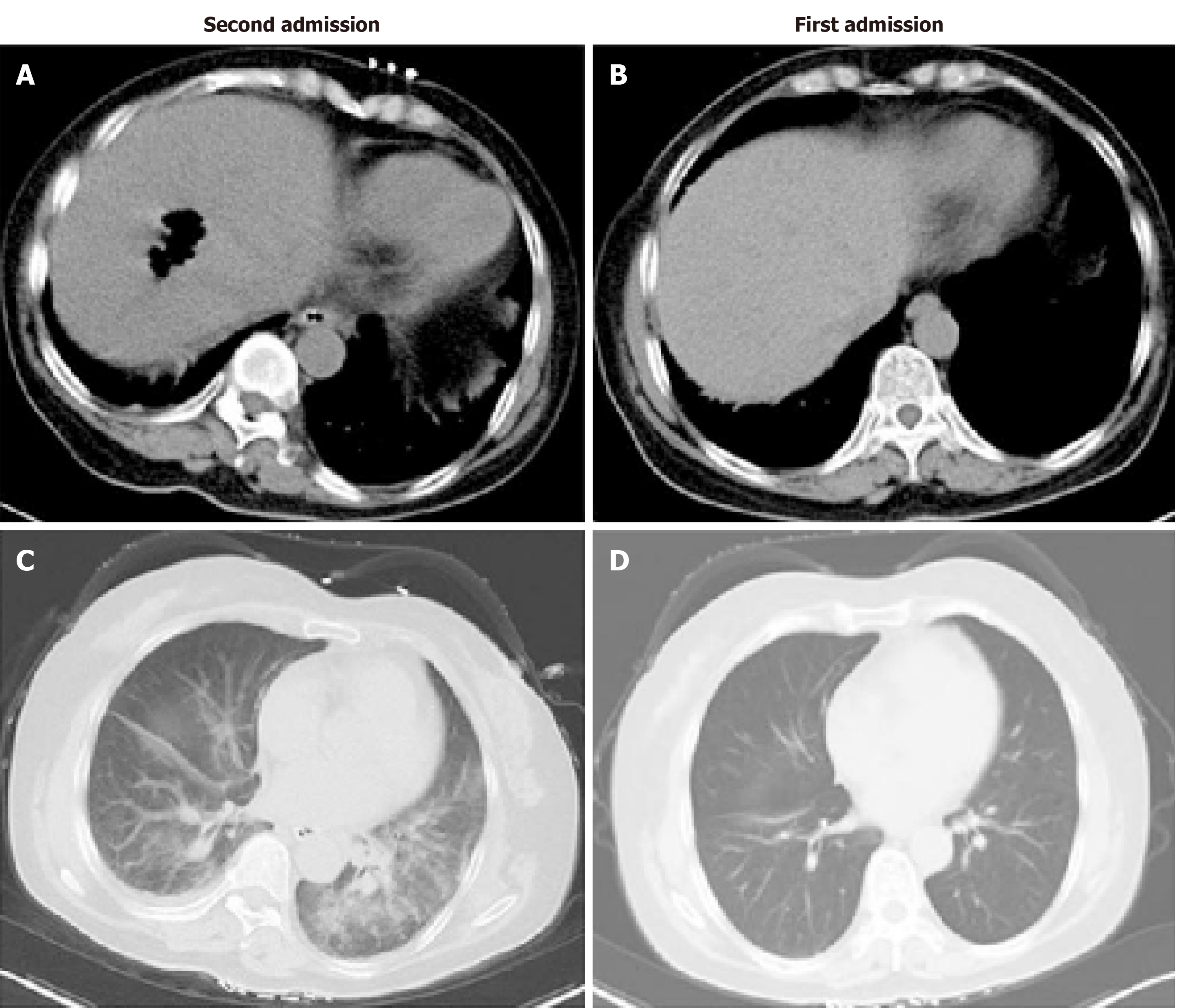

The patient presented to the emergency room again the next day (January 9) because of similar symptoms and was admitted to the hepatopancreatobiliary surgery ward immediately. She walked into the ward by herself with normal temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and OS. Two hours later, she went to the lavatory and urinated, and the urine color was like soy sauce. After going back to bed, OS decreased to 77%, and she developed consciousness disturbance. Mask oxygen inhalation was given. Routine blood tests, serum electrolytes, blood coagulation function, biochemical markers of myocardial injury, renal function, liver function, and arterial blood gas analysis were assessed (Tables 1-3). Consciousness recovered a little, and OS recovered to around 90% before trachea cannula. Blood pressure was 130/90 mmHg, and heart rate was 130 bpm. The clinical laboratory of our hospital reported that the patient’s blood was abnormal and could not be analyzed properly. Arterial blood gas analysis showed tHb 6.6 g/dL and PO2 54.705 mmHg. The patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit. She had a chest and abdominal CT scan, which revealed liver abscess and bilateral pneumonia (Figure 2). Because of progressive respiratory distress and hypoxia, the patient was treated by mechanical ventilation along with trachea cannula, central venous catheterization, urethral catheterization, electrocardiogram monitoring, fluid resuscitation, epinephrine to maintain blood pressure, and sodium bicarbonate solution to improve acidosis. After 8 h in the hospital, she had a high fever of 40 °C, blood was drawn for culture, and 3 g IV of cefoperazone/sulbactam was administered.

| Second admission | First admission | Normal range | |

| White blood cells (109/L) | 29.50 | 15.83 | 4-10 |

| Red blood cells (1012/L) | 1.88 | 4.28 | 3.5-5.5 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 64 | 132 | 110-160 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 13.5 | 38.4 | 37-49 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 71.8 | 89.7 | 80-100 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (pg) | 34 | 30.9 | 27-32 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (g/L) | 474 | 344 | 320-360 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 95 | 181 | 100-300 |

| Second admission | Normal range | |

| Total protein (g/L) | 118.6 | 60-80 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 56.1 | 35-55 |

| Prealbumin (mg/L) | 96 | 200-400 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) | 128.3 | 5.1-20.4 |

| Direct bilirubin (µmol/L) | 86.3 | 1.7-6.8 |

| Total bile acid (µmol/L) | 30.9 | 1-7 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 430 | 34-114 |

| γ-glutaryl transferase (U/L) | 481 | 11-50 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L) | 310 | 5-40 |

| Second admission | Normal range | |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 135.6 | 135-145 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.95 | 3.6-5.5 |

| Chlorinum (mmol/L) | 102.1 | 96-106 |

About 12 h after walking into the ward by herself, she had a cardiac arrest and died shortly thereafter. About 2 d after her death, blood culture confirmed a C. perfringens infection. Table 4 summarizes the clinical events.

| Time | Event | |

| January 8 | 16:30 | First admission to the emergency room |

| 17:00-18:00 | Urine amylase at 10403 U/L (normal: 47-458), first CT, first blood routine test, blood amylase at 1006 U/L (normal: < 100) | |

| The end | Refused hospitalization, anti-pancreatitis treatment in the emergency room | |

| January 9 | 11:00 | Second admission to the emergency room |

| 12:00 | Hospitalization, walked into the general ward | |

| 13:45 | Consciousness disturbance, oxygen saturation 77% | |

| 14:30 | Consciousness recovered a little, oxygen saturation 90% | |

| 16:00 | Second CT on the way to the ICU | |

| 17:12 | Second blood routine test, liver function | |

| 21:42 | High fever of 40 °C, blood culture | |

| 22:18 | Cefoperazone/sulbactam was administered | |

| January 10 | 00:30 | Cardiac arrest |

| 01:30 | Death | |

| January 13 | 10:40 | The result of the blood culture confirmed Clostridium perfringens infection |

C. perfringens is an anaerobic Gram-positive rod bacterium. It can be found in the soil and the human gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts. C. perfringens is an opportunistic pathogen. It can cause infection when the body displays underlying conditions, including poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, underlying malignancy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy[5]. Chen et al[6] reported that among the patients with C. perfringens infection, diabetes mellitus and liver cirrhosis were the most common underlying diseases in Tainan (China). Fujita et al[7] reported that eight of 18 patients with C. perfringens had diseases of the hepatobiliary tract system. Pancreatic infection by this agent can occur by three means: Migration by direct contact with a vulnerable colon, by retrograde duodenal infection, or through the biliary tree. Nevertheless, C. perfringens secondary to acute pancreatitis is very rare. A case of C. perfringens was reported to be secondary to acute necrotizing pancreatitis[8], which is a very severe condition, while the patient reported here had mild acute pancreatitis.

In the case reported here, the patient had no immunosuppressive conditions such as chemotherapy, current radiation treatments, and treatment with steroids and no medical history of diabetes mellitus, malignancy, or liver cirrhosis. Nevertheless, acute pancreatitis may have a “trigger effect”. During the early stage of acute pancreatitis, massive amounts of cytokines induced by local pancreatic inflammation enter the bloodstream, leading to damage to the intestinal barrier function and an increase of mucous permeability. The intestinal bacteria gain access to the lymphatic or portal system, and finally, reach every part of the body. The translocated bacteria are mainly composed of opportunistic pathogens from the gut, including Escherichia coli, Shigella flexneri, enteric Bacilli, Acinetobacter, Bacillus coagulans, and enterococcus, among others[9]. Li et al[10] detected bacterial DNA from peripheral blood in 68.8% of patients with acute pancreatitis. As it is found in the guts, C. perfringens can also translocate to the circulatory system. Since there are no other sources of C. perfringens in blood, translocation of intestinal bacteria according to acute pancreatitis may the only way.

There are five serotypes of C. perfringens (A, B, C, D, and E), and they can produce four toxins (α, β, ε, and ι). The α-toxin, mostly in C. perfringens type A, is regarded as a key pathogenic factor in the destruction of soft tissue and the development of gangrene and gas-forming abscesses. It can disrupt the membrane of the erythrocytes due to phospholipase C activity, which leads to hemolysis. In addition, bilirubin, potassium, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels can be elevated[11]. Acute massive intravascular hemolysis only occurs in 7%-15% of C. perfringens bacteremia cases, but it is typically the most severe complication, with a mortality rate of 70%-100%[12]. In the patient reported here, the clinical course was very aggressive. The patient had a severe OS decrease and consciousness disturbance after 2 h of admission and was dead about 10 h later. According to the subsequent blood test and CT scan, the patient had acute massive intravascular hemolysis because of C. perfringens bacteremia, which also caused the gas-forming liver abscess and bilateral pneumonia.

Infection with C. perfringens often progresses rapidly to death, and rapid recognition is critical for patient survival[1-3,13]. The key to patient rescue is how fast the appropriate treatments are started. The diagnosis and management of the patient reported here were clearly inadequate. The liver abscess was found only 9 h before the patient’s death, and no drainage was performed. The specimen from the abscess can be immediately used for Gram staining. C. perfringens is a Gram-positive bacillus and has a distinctive form and we suspect a C. perfringens infection. Actually, even until death, the actual condition was not recognized, and no proper action was taken. We gave antibiotics only when the patient had a high fever but not as soon as the gas-forming liver abscess and bilateral pneumonia were found, and we did not know whether the appropriate antibiotic was given. Finally, a peripheral blood smear was not prepared, missing the opportunity to observe the typically abnormal blood cell. Blood smear is not useful for diagnosis of C. perfringens because of the small amount of inclusive bacteria, but anaerobic culturing of blood might be useful even though several days are needed. We believe that a lack of proper knowledge about C. perfringens infection was the main reason for the diagnostic and management failure.

For a patient with sepsis and intravascular hemolysis, the possibility of C. perfringens infection must remain[14]. For the early diagnosis of C. perfringens infection, Gram staining of the blood or drainage sample is important. The early signs of hemolysis are elevated LDH, total or indirect bilirubin, and potassium. Spherocytes or ghost cells may be found in the blood smears. A red serum or hemoglobinuria may be observed after substantial hemolysis[15].

When C. perfringens septicemia is suspected, aggressive management is warranted as early as possible[1-3]. The management includes timely debridement or drainage of the abscess, initiation of appropriate antibiotics without delay, and circulatory support with a multidisciplinary team approach[15]. When surgical debridement is difficult, hyperbaric oxygen therapy is worth and may reduce mortality; the suggested regimen is 2-3 atm oxygen for 60-120 min per session with 2-3 sessions per day for up to 6 d[16]. The appropriate antibiotic is intravenously administrated high-dose penicillin (10-24 million U daily). Shah et al[17] classified antibiotics into “appropriate” and “insufficient”. The most commonly used “appropriate” antibiotics for C. perfringens are penicillin G, clindamycin, metronidazole, and piperacillin/tazobactam. Patients treated with “insufficient” antibiotics had a significantly higher 2-d mortality rate (75%) compared with patients treated with “appropriate” antibiotics (12.5%). In vivo studies showed that the combination of penicillin and clindamycin has better efficacy than penicillin alone in the suppression of toxin synthesis[16].

The translocated bacteria in patients with acute pancreatitis can include C. perfringens, which has a very poor prognosis, regardless of the patient’s condition. Once a C. perfringens infection is suspected, aggressive management should be started as soon as possible.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D, D, D, D

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Alconchel F, de Nucci G, Kitamura K, Lisotti A, Strainiene S, Tanabe H, Tanabe K, Velikova T, Yamaguchi A S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Zane S, Guarner J. Gynecologic clostridial toxic shock in women of reproductive age. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13:561-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stevens DL, Aldape MJ, Bryant AE. Life-threatening clostridial infections. Anaerobe. 2012;18:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Aldape MJ, Bryant AE, Stevens DL. Clostridium sordellii infection: epidemiology, clinical findings, and current perspectives on diagnosis and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1436-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4345] [Article Influence: 362.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 5. | Rajendran G, Bothma P, Brodbeck A. Intravascular haemolysis and septicaemia due to Clostridium perfringens liver abscess. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38:942-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen YM, Lee HC, Chang CM, Chuang YC, Ko WC. Clostridium bacteremia: emphasis on the poor prognosis in cirrhotic patients. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2001;34:113-118. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Fujita H, Nishimura S, Kurosawa S, Akiya I, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Ohnishi K. Clinical and epidemiological features of Clostridium perfringens bacteremia: a review of 18 cases over 8 year-period in a tertiary care center in metropolitan Tokyo area in Japan. Intern Med. 2010;49:2433-2437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Castro R, Mendes J, Amaral L, Quintanilha R, Rama T, Melo A. Clostridium perfringens's necrotizing acute pancreatitis: a case of success. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;2017:rjx116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cen ME, Wang F, Su Y, Zhang WJ, Sun B, Wang G. Gastrointestinal microecology: a crucial and potential target in acute pancreatitis. Apoptosis. 2018;23:377-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li Q, Wang C, Tang C, He Q, Li N, Li J. Bacteremia in patients with acute pancreatitis as revealed by 16S ribosomal RNA gene-based techniques*. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1938-1950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shindo Y, Dobashi Y, Sakai T, Monma C, Miyatani H, Yoshida Y. Epidemiological and pathobiological profiles of Clostridium perfringens infections: review of consecutive series of 33 cases over a 13-year period. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:569-577. [PubMed] |

| 12. | García Carretero R, Romero Brugera M, Vazquez-Gomez O, Rebollo-Aparicio N. Massive haemolysis, gas-forming liver abscess and sepsis due to Clostridium perfringens bacteraemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Simon TG, Bradley J, Jones A, Carino G. Massive intravascular hemolysis from Clostridium perfringens septicemia: a review. J Intensive Care Med. 2014;29:327-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cochrane J, Bland L, Noble M. Intravascular Hemolysis and Septicemia due to Clostridium perfringens Emphysematous Cholecystitis and Hepatic Abscesses. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:523402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kurasawa M, Nishikido T, Koike J, Tominaga S, Tamemoto H. Gas-forming liver abscess associated with rapid hemolysis in a diabetic patient. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:224-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 16. | Law ST, Lee MK. A middle-aged lady with a pyogenic liver abscess caused by Clostridium perfringens. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:252-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shah M, Bishburg E, Baran DA, Chan T. Epidemiology and outcomes of clostridial bacteremia at a tertiary-care institution. ScientificWorldJournal. 2009;9:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |