Published online Jun 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4348

Peer-review started: January 20, 2021

First decision: February 11, 2021

Revised: February 23, 2021

Accepted: April 12, 2021

Article in press: April 12, 2021

Published online: June 16, 2021

Processing time: 126 Days and 8.2 Hours

Infective endocarditis is more common in hemodialysis patients than in the general population and is sometimes difficult to diagnose. Isolated coronary sinus (CS) vegetation is extremely rare and has a good prognosis, but complicated CS vegetation may have a poorer clinical course. We report a case of CS vegetation accidentally found via echocardiography in a hemodialysis patient with undifferentiated shock. The CS vegetation may have been caused by endocardial denudation due to tricuspid regurgitant jet and subsequent bacteremia.

A 91-year-old man with dyspnea and hypotension was transferred from a nursing hospital. He was on regular hemodialysis and had a history of severe grade of tricuspid regurgitation. There was no leukocytosis or fever upon admission. Repetitive and sequential blood cultures revealed absence of microorganism growth. Chest computed tomography showed lung consolidation and a large pleural effusion. A mobile band-like mass on the CS, suggestive of vegetation, was observed on echocardiography. We diagnosed him with infective endocarditis involving the CS, pneumonia, and septic shock based on echocardiographic, radiographic, and clinical findings. Infusion of broad-spectrum antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, inotropic support, and ventilator care were performed. However, the patient died from uncontrolled infection and septic shock.

CS vegetation can be fatal in hemodialysis patients with impaired immune systems, especially when it delays the diagnosis.

Core Tip: Coronary sinus vegetation is rarely observed. It might also be confused with a coronary sinus thrombosis and inappropriately managed. We present a case of coronary sinus vegetation with typical echocardiographic findings and review clinical challenges, including differential diagnoses and therapeutic options, associated with treating hemodialysis patients suspected to have coronary sinus endocarditis.

- Citation: Hwang HJ, Kang SW. Coronary sinus endocarditis in a hemodialysis patient: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(17): 4348-4356

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i17/4348.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4348

Infective endocarditis in hemodialysis patients is more common and has higher morbidity and mortality than that in the general population[1,2]. Although infective endocarditis in hemodialysis patients occurs due to vascular access-related infection during dialysis, it mainly involves left-sided heart structures, while right-sided structures are rarely affected[2]. Right-sided infective endocarditis (RIE) accounts for 5%-10% of all cases of infective endocarditis and frequently affects intravenous drug users or patients with central venous catheters or intracardiac devices[3]. RIE usually involves the tricuspid or pulmonary valves and often leads to secondary right heart failure[3]. This report shows an elderly hemodialysis patient with coronary sinus (CS) endocarditis who presented with septic shock. CS endocarditis has rarely been reported and usually has a good prognosis[4], but it was fatal in our case. We review the clinical challenges that caused a poor clinical outcome in our case, including differential diagnosis and therapeutic options in hemodialysis patients with endocarditis.

A 91-year-old male patient admitted to a nursing hospital was transferred to our hospital with dyspnea, cough, and a confused mental state.

Prior to patient transfer, a single dose of moxifloxacin was administered at the nursing hospital without blood culture tests. Oxygen was administered via a nasal cannula during the transfer.

The patient has undergone regular hemodialysis for one year. He had a medical history of atrial fibrillation, severe grade of tricuspid and mitral regurgitation, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He also had a stroke 5 years previously.

At the time of admission in our institution, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and body temperature of the patient were 85/40 mmHg, 110 /min, 20 /min, and 36.5 °C, respectively.

Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 8780 /μL (neutrophils: 78%), C-reactive protein level of 1.6 mg/dL (normal range < 0.5 mg/dL), procalcitonin level of 0.571 μg/L (normal range < 0.046 μg/L), creatinine level of 5.6 mg/dL (glomerular filtration rate by the modification of diet in renal disease study equation = 10 mL/min/1.73 m2), and brain natriuretic peptide level of 124 ng/L (normal range < 100 ng/L). Arterial blood gas analysis during oxygen supply revealed severe acidosis with a pH of 7.173, partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 66 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen of 100 mmHg, and bicarbonate of 24 mEq/L.

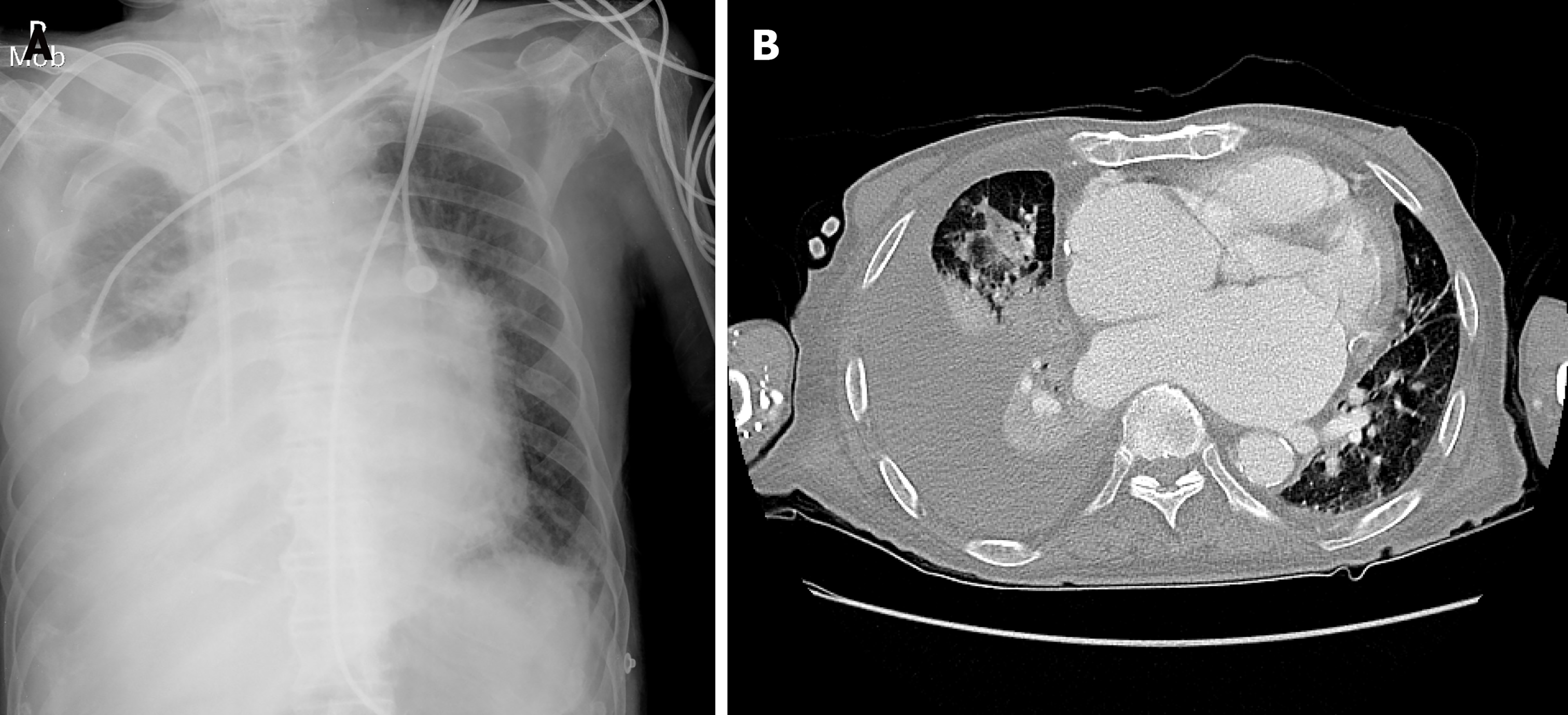

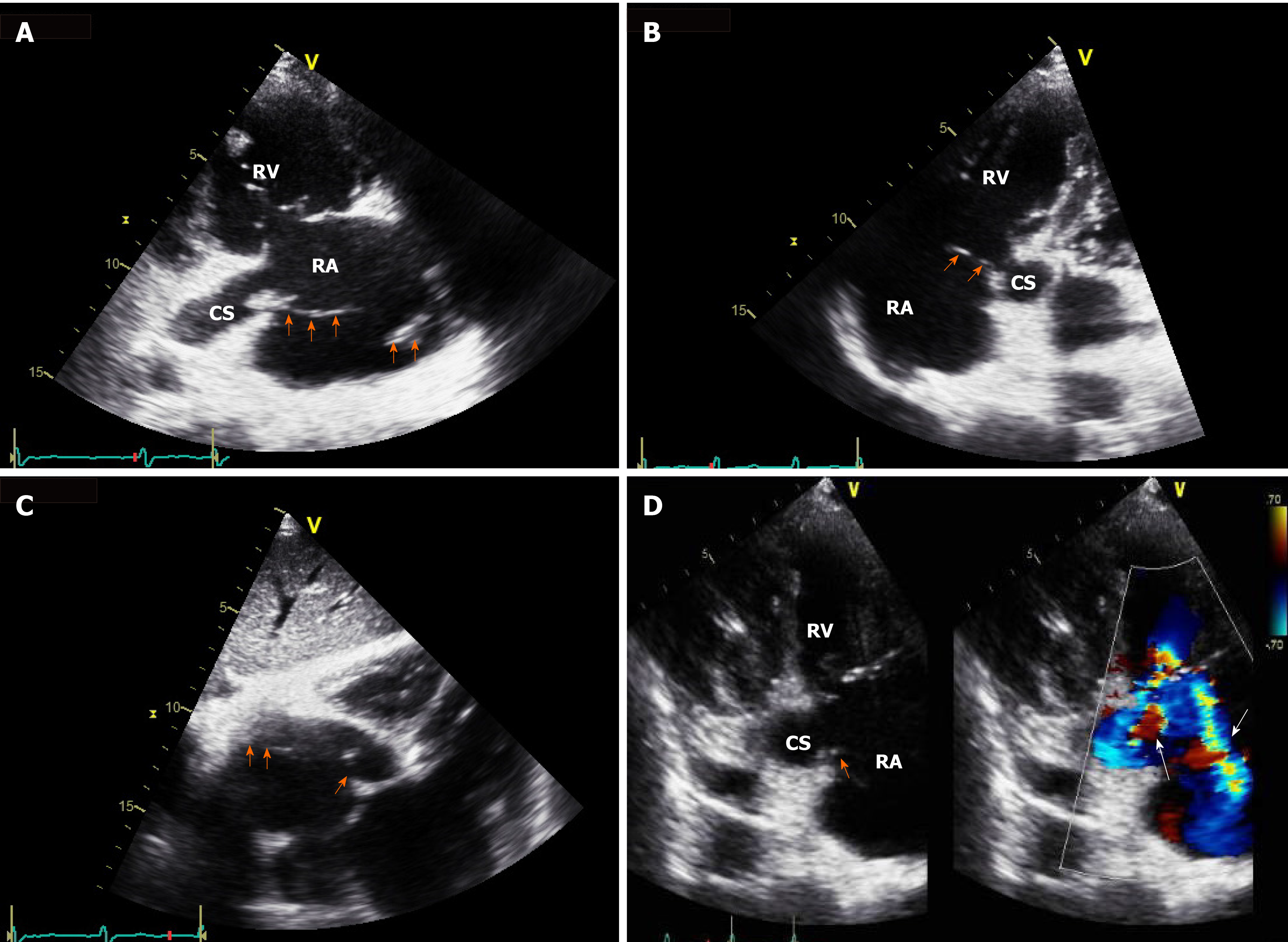

Chest radiography revealed a large right pleural effusion and pulmonary edema (Figure 1A). Chest computed tomography showed consolidation in the right upper and middle lobes and total atelectasis of the right lower lobe (Figure 1B). The pleural effusion was a transudate, according to the following Light’s criteria[5]: Pleural fluid protein-to-serum protein ratio of 0.4; pleural fluid lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) -to-serum LDH of 0.6; and pleural fluid LDH to the upper normal limit for serum of 0.6. There was no growth of microorganisms on pleural fluid culture. Transthoracic echocardiography showed a moderate grade of eccentric tricuspid regurgitant jet flow directed towards the CS and a mobile band-like echogenic mass (longitudinal dimension of approximately 8 cm) attached to the ostium of the CS and posterolateral wall of the right atrium, suggesting the presence of vegetation (Figure 2 and Supplementary Videos 1-3, which demonstrate a vegetation on echocardiography). He also had a moderate grade of pulmonary hypertension (estimated systolic pulmonary arterial pressure = 61 mmHg) and right atrial enlargement (30 cm2). Other cardiac structures, including the valves, were unaffected, and the left ventricular ejection fraction was normal. There was no radiographic evidence of pulmonary thromboembolism or deep vein thrombosis. Sequential blood culture results were negative.

The patient was diagnosed with septic shock due to CS endocarditis and pneumonia. Respiratory acidosis with metabolic decompensation was accompanied by severe infection, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypoventilation, and a large pleural effusion.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, including teicoplanin and meropenem, were admini

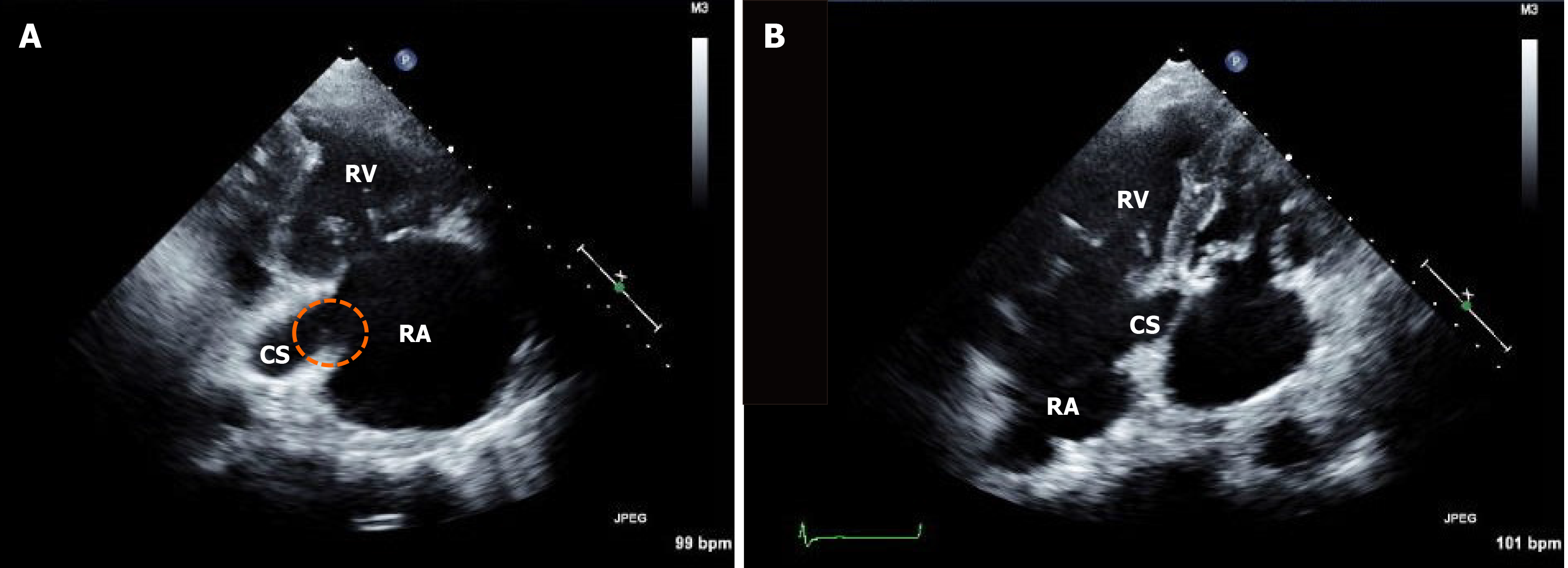

Hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis were improved to some extent after insertion of the chest tube and application of the mechanical ventilator (pH = 7.347, partial pressure of carbon dioxide = 41 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen = 97 mmHg, and bicarbonate = 22 mEq/L on arterial blood gas analysis). Follow-up echocardiography after one week showed remnants of vegetation (Figure 3), suggesting migration of the cardiac vegetation into the lung. There was no abrupt hypoxic event that could lead to deterioration. However, leukocytosis and metabolic and respiratory acidosis worsened over time [white blood cell count, 33830 /μL (neutrophils, 90%); pH = 7.160, partial pressure of carbon dioxide = 52 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen = 73 mmHg, bicarbonate 18 mEq/L, lactic acid = 3.6 mmol/L on arterial blood gas analysis]. Septic shock persisted despite medical support and he eventually died.

The CS is a structure that receives approximately 60% of the total cardiac venous supply and drains into the right atrium[6]. It is mainly injured during right cardiac procedures, including insertion of central venous catheter, cannulation of the CS during heart surgery, electrophysiologic study, and placement of intracardiac devices[6]. Unlike traumatic injury, spontaneous endothelial injury of the CS has been reported in some conditions causing accelerating or turbulent jet flow in the CS, such as coronary arteriovenous fistula between the left circumferential artery and CS and eccentric tricuspid regurgitation towards the CS[4,7-9]. In our case, the substantial tricuspid regurgitant jet flow directed towards the CS and posterolateral right atrial surface might have caused endothelial denudation; subsequently, bacteremia during hemodialysis or sepsis due to pneumonia probably led to the formation of vegetation at that location.

Vegetation of the CS resembles thrombosis in appearance. However, both need to be distinguished because they require different treatments. CS vegetation, including infective endocarditis or septic thrombophlebitis, has been reported in 13 cases, including our case (Table 1)[4,7-17]. According to these cases, patients with CS vegetation mainly had symptoms and signs of infection, such as fever and leukocy

| Ref. | Age/sex | Symptoms | Characteristics of vegetation in the CS | Associated pathology | Pathogen | Therapy | Events |

| Cases of infective endocarditis | |||||||

| Takashima et al[7], 2016 | 64/M | Fever, fatigue | A sessile mass with mobile multi-lobules on the CS lumen | CAVF, vegetation on the MV and AV with moderate regurgitation, acute HF | Negative results in BC, Corynebacterium species in TC | Surgery | Multi-organ failure, DIC, died |

| Kasravi et al[8], 2004 | 31/M | Fever, pleuritic chest pain | A mobile and multi-lobulated mass protruding from the CS to the RA | CAVF | MSSA in BC | Surgery | SE (lung) and DIC, recovered |

| Song et al[4], 2018 | 71/M | Fever, chest pain, hemoptysis | A banded mobile mass in the CS | ASD, PLSVC, severe eccentric TR jet to the CS, RV dysfunction with RAE, moderate PHT | MSSA in BC | Surgery | SE (lung), recovered |

| Kumar et al[10], 2016 | 27/F | Septic shock | A pedunculated mobile mass 1 cm proximal from the CS orifice to the Eustachian valve | IVDU | MSSA in BC | Antibiotics | SE (lung, viscera), recovered |

| Machado et al[11], 2010 | 44/M | Fever, dyspnea | A mobile mass originating in the CS orifice, extending to the RA | Purulent pericardial effusion | MSSA in BC | Surgery | Recovered |

| Gill et al[12], 2005 | 37/M | Fever, weight loss | A mobile mass in the CS and CAVF | CAVF | Streptococcus mitis in BC | Antibiotics | Recovered |

| Theodoropoulos et al[9], 2016 | 28/F | Fever, hemoptysis | Two mobile masses towards the CS orifice and in the CS lumen | IVDU, eccentric moderate TR jet to the CS | Group C Streptococcus in BC | Antibiotics | Recovered |

| Kwan et al[13], 2014 | 23/F | Fever | A mobile round mass protruding from the CS orifice | HD | Acinetobacter baumanii in BC | Antibiotics | Recovered |

| Our case | 91/M | Septic shock | A mobile band-like mass protruding from the CS orifice | HD, eccentric moderate TR jet to the CS | Negative results in BC | Antibiotics | Died |

| Cases of septic thrombophlebitis | |||||||

| Ross et al[14], 1985 | 31/M | Fever, dyspnea | Occlusion of the CS orifice by fungal thrombi (in necropsy) | Lymphoma, occlusion of the LCA by fungal thrombi (in necropsy) | Negative results in fungal culture, Aspergillus fumigatus in the lung, LCA and CS | Antibiotics | Died |

| Dryer et al[15], 1976 | 20/M | Fever, disturbed mental state | Occlusion of the CS orifice by septic thrombophlebitis (in necropsy) | IVDU, vegetation on the MV, multi-organ embolic infarction (in necropsy) | MSSA in BC | Antibiotics | SE (muti-organs), died |

| Jones et al[16], 2004 | 50/M | Fever | A mass protruding from the CS orifice to the RA, and extending to the posterior interventricular vein | Previous pericardiectomy due to purulent pericarditis, recurrent furunculosis | MSSA in BC | Surgery | SE (lung), recovered |

| Fournet et al[17], 2014 | 38/F | Fever, chest pain, | A mobile mass originating from the CS ostium with heterogeneous solid material | Purulent pericardial effusion | MSSA in BC | Antibiotics | SE (lung), recovered |

Although vegetation or thrombosis of the CS is confirmed based on histopathological findings, echocardiography is the best imaging technique for screening. However, minor structures of the right heart, such as the CS and Chiari network, are sometimes overlooked during echocardiography. This might be one of the reasons why cases were rarely reported. In our case, infective endocarditis was not suspected before echocardiography because typical microorganisms did not grow in blood cultures, and only non-specific hypotension and mild elevation of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels were observed without typical infection signs. In fact, echocardiography was performed to screen for cardiogenic shock, and CS vegetation was incidentally observed. We immediately started broad-spectrum antibiotics for infective endocarditis and found no vegetation on the follow-up echocardiography. If the echogenic mass had continued to increase, it might have caused other clinical problems due to mechanical obstruction or destruction of structures adjacent to the CS. Although immediate treatment with antibiotics did not alter the prognosis of this patient, early detection of CS vegetation is essential for appropriate management.

The mortality rate of RIE including CS endocarditis[4] is considered to be lower than that of left-sided infective endocarditis (LIE)[3]. However, a high proportion (60%-80%) of intravenous drug users, who generally display a benign clinical course, might account for the good prognosis of RIE in previous studies[29,30]. Indeed, recent studies that enrolled patients with no history of intravenous drug use or with cardiac devices showed similar in-hospital mortality rates between RIE and LIE[31,32]. Furthermore, hemodialysis patients with inherently impaired immune systems are highly susceptible to bacteremia and septic shock. In our case, the patient died because his immune systems were impaired due to old age, chronic renal impairment, fragility, and severe infection. Moreover, the diagnosis of infective endocarditis was delayed due to atypical symptoms. His negative blood culture results might also be associated with poor outcome because it made antibiotic selection difficult.

The diagnosis and treatment of infective endocarditis in hemodialysis patients is challenging. Clinical manifestations, including fever and leukocytosis, may be atypical because of impaired cellular host defense; thus, diagnosis or management of infective endocarditis may be delayed[2]. Indwelling intravascular catheters may be a primary source of pathogens; however, removal of the catheter is not always possible or necessary[2]. Infective endocarditis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is a common clinical entity. However, empirical use of vancomycin before the isolation of microorganisms should be determined carefully because vancomycin has a slower bactericidal effect on methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus compared to beta-lactam antibiotics[2,33].

Infective endocarditis is more common and has a poorer prognosis in hemodialysis patients than it does in the general population. Thus, echocardiography should be thoroughly investigated in hemodialysis patients suspected of having sepsis or shock. In addition, CS vegetation is easy to be misdiagnosed when the clinician is not cautious or inexperienced. The treatment of infective endocarditis in hemodialysis patients is more challenging when blood cultures are negative. More careful consideration and a team-based approach involving cardiologists, nephrologists, and infectious disease specialists, is needed for the treatment of infectious diseases in hemodialysis patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shuang WB, Zhu F S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Maraj S, Jacobs LE, Kung SC, Raja R, Krishnasamy P, Maraj R, Braitman LE, Kotler MN. Epidemiology and outcome of infective endocarditis in hemodialysis patients. Am J Med Sci. 2002;324:254-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nucifora G, Badano LP, Viale P, Gianfagna P, Allocca G, Montanaro D, Livi U, Fioretti PM. Infective endocarditis in chronic haemodialysis patients: an increasing clinical challenge. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2307-2312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, El Khoury G, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Snygg-Martin U, Thuny F, Tornos Mas P, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3075-3128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2661] [Cited by in RCA: 3356] [Article Influence: 335.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Song G, Zhang J, Zhang X, Yang H, Huang W, Du M, Zhou K, Ren W. Right-sided infective endocarditis with coronary sinus vegetation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2018;18:111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, Ball WC Jr. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1087] [Cited by in RCA: 1048] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Takashima A, Yagi S, Yamaguchi K, Takagi E, Kanbara T, Ogawa H, Ise T, Kusunose K, Tobiume T, Yamada H, Soeki T, Wakatsuki T, Kitagawa T, Sata M. Vegetation in the coronary sinus that concealed the presence of a coronary arteriovenous fistula in a patient with infectious endocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2016;207:266-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kasravi B, Reid CL, Allen BJ. Coronary artery fistula presenting as bacterial endocarditis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:1315-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Theodoropoulos KC, Papachristidis A, Walker N, Dworakowski R, Monaghan MJ. Coronary sinus endocarditis due to tricuspid regurgitation jet lesion. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;18:382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kumar KR, Haider S, Sood A, Mahmoud KA, Mostafa A, Afonso LC, Kottam AR. Right-sided endocarditis: eustachian valve and coronary sinus involvement. Echocardiography. 2017;34:143-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Machado MN, Nakazone MA, Takakura IT, Silva CM, Maia LN. Spontaneous Bacterial Pericarditis and Coronary Sinus Endocarditis Caused by Oxacillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010:984562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gill DS, Yong QW, Wong TW, Tan LK, Ng KS. Vegetation and bilateral congenital coronary artery fistulas. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:492-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kwan C, Chen O, Radionova S, Sadiq A, Moskovits M. Echocardiography: a case of coronary sinus endocarditis. Echocardiography. 2014;31:E287-E288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ross EM, Macher AM, Roberts WC. Aspergillus fumigatus thrombi causing total occlusion of both coronary arterial ostia, all four major epicardial coronary arteries and coronary sinus and associated with purulent pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56:499-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dryer R, Goldman D, Nelson R. Letter: Septic thrombophlebitis of the coronary sinus in aucte bacterial endocarditis. Lancet. 1976;2:369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jones D, Amsterdam E, Young JN. Septic thrombophlebitis of the coronary sinus with complete recovery after surgical intervention. Cardiol Rev. 2004;12:325-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fournet M, Behaghel A, Pavy C, Flecher E, Thebault C. Spontaneous bacterial coronary sinus septic thrombophlebitis treated successfully medically. Echocardiography. 2014;31:E92-E93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Floria M, Negru D, Antohe I. Coronary sinus thrombus without spontaneous contrast. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;42:421-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Neri E, Tripodi A, Tucci E, Capannini G, Sassi C. Dramatic improvement of LV function after coronary sinus thromboembolectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:961-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hart MA, Simegn MA. Pylephlebitis presenting as spontaneous coronary sinus thrombosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moey MYY, Ebin E, Marcu CB. Venous varices of the heart: a case report of spontaneous coronary sinus thrombosis with persistent left superior vena cava. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2018;2:yty092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ramsaran EK, Sadigh M, Miller D. Sudden cardiac death due to primary coronary sinus thrombosis. South Med J. 1996;89:531-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kachalia A, Sideras P, Javaid M, Muralidharan S, Stevens-Cohen P. Extreme clinical presentations of venous stasis: coronary sinus thrombosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61:841-843. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Parmar RC, Kulkarni S, Nayar S, Shivaraman A. Coronary sinus thrombosis. J Postgrad Med. 2002;48:312-313. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Martin J, Nair V, Edgecombe A. Fatal coronary sinus thrombosis due to hypercoagulability in Crohn's disease. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2017;26:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Frogel JK, Weiss SJ, Kohl BA. Transesophageal echocardiography diagnosis of coronary sinus thrombosis. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:441-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kitazawa S, Kitazawa R, Kondo T, Mori K, Matsui T, Watanabe H, Watanabe M. Fatal cardiac tamponade due to coronary sinus thrombosis in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Al-Turki MA, Patton D, Crean AM, Horlick E, Dhillon R, Johri AM. Spontaneous Thrombosis of a Left Circumflex Artery Fistula Draining Into the Coronary Sinus. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2015;6:640-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Thalme A, Westling K, Julander I. In-hospital and long-term mortality in infective endocarditis in injecting drug users compared to non-drug users: a retrospective study of 192 episodes. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:197-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Moss R, Munt B. Injection drug use and right sided endocarditis. Heart. 2003;89:577-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee MR, Chang SA, Choi SH, Lee GY, Kim EK, Peck KR, Park SW. Clinical features of right-sided infective endocarditis occurring in non-drug users. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:776-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ortiz C, López J, García H, Sevilla T, Revilla A, Vilacosta I, Sarriá C, Olmos C, Ferrera C, García PE, Sáez C, Gómez I, San Román JA. Clinical classification and prognosis of isolated right-sided infective endocarditis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hoen B. Infective endocarditis: a frequent disease in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:1360-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |