Published online Jun 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4253

Peer-review started: December 15, 2020

First decision: December 28, 2020

Revised: January 8, 2021

Accepted: February 26, 2021

Article in press: February 26, 2021

Published online: June 16, 2021

Processing time: 156 Days and 5.4 Hours

There have been few reports on level 3 difficult removal of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in neonates. Here, we reported a case of an extremely preterm infant who underwent level 3 difficult removal of a PICC.

Female baby A, weighing 1070 g at 27+1 wk of gestational age, was diagnosed with extremely preterm infant and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. She underwent PICC insertion twice. The first PICC insertion went well; the second PICC was inserted in the right lower extremity, however, phlebitis occurred on the second day after the placement. On the third day of catheterization, phlebitis was aggravated, while the right leg circumference increased by 2.5 cm. On the fourth day of catheterization, more red swelling was found in the popliteal part, covering an area of about 1.5 cm × 4 cm, which was diagnosed as phlebitis level 3; thus, we decided to remove the PICC. During tube removal, the catheter rebounded and could not be pulled out (several conventional methods were performed). Finally, we successfully removed the PICC using a new approach termed “AFGP”. On the 36th day of admission, the baby fully recovered and was discharged.

The “AFGP” bundle approach was effective for an extremely preterm infant, who underwent level 3 difficult removal of a PICC.

Core Tip: We report a rare case of an extremely preterm infant who underwent level 3 difficult removal of a peripherally inserted central catheter. We faced unprecedented difficulties and challenges during tube removal and several conventional methods were performed. Finally, we successfully removed the peripherally inserted central catheter using a new approach “AFGP,” where “A” indicates assessment, “F” refers to finding reasons, “G” refers to general nursing, and “P” indicates phentolamine for moist heat application.

- Citation: Chen Q, Hu YL, Su SY, Huang X, Li YX. “AFGP” bundles for an extremely preterm infant who underwent difficult removal of a peripherally inserted central catheter: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(17): 4253-4261

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i17/4253.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4253

A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is a device inserted into a peripheral vein and threaded into the central venous circulation, with the catheter tip in the superior vena cava or inferior vena cava[1-3]. As an important life channel for extremely preterm infants, PICC plays a vital role in long-term hyperalimentation and medication administration. The use of PICC can prevent repeated venipuncture in infants and ensure the supply of parenteral nutrition, as well as the timely administration of medication during the rescue. Some complications include occlusion, central line-associated blood-stream infection, phlebitis, and nonselective removal[4,5]. Difficulty removing these lines is a rare complication, with rates varying between 0.34% and 8.40%[6-8]. Long et al[6] reported that the incidence of PICC extraction difficulty is 0.34% in cancer patients in China. Another study conducted in the United States reported that 8.40% of adults experience difficult removal[8]. Regarding children, Wall’s study showed that the incidence of difficult PICC removal was 0.96% in Ohio, United States[7]; yet, there have been no reports on the incidence of difficult PICC removal in neonates. Difficult PICC removal is divided into four levels: First level at which no pulling sensation is observed, followed by the second levels, at which a feeling of pulling is observed. There is elastic retraction at the third level, followed by complete unplugging as the fourth level. Multiple factors that can contribute to difficult PICC removal include venous vasospasm, knotting, entanglement, adhesion to venous endothelium, thrombus, and fibrin formation around the catheter[9]. These complications can cause PICC fracture and fragment embolization. They can also be catastrophic due to the risk of potential cardiac or pulmonary emboli[10].

Generally, the following methods are used for difficult PICC removal in adults and children: Vasodilatation with a topical glyceryl trinitrate patch proximal to the insertion site[11]; warm and moist compresses, which are very useful in patients[9]; relaxation techniques, which may reduce autonomic vasospasm[11]; and surgical removal, which may be necessary as a last resort after all other methods have failed[11]. Nonetheless, the present case was special since the subject was an extremely preterm infant. Considering the adverse effects of glyceryl trinitrate on infants, it could not be used in the present case. At the same time, surgical removal would be a substantially traumatic experience for such an extremely preterm infant. Also, we tried to use relaxation techniques to reduce vasospasm, such as saline solution for warm, moist compresses. Unfortunately, these methods did not work in our case.

Herein, we present a case study of an extremely preterm infant who underwent level 3 difficult removal of a PICC in the neonatal intensive care unit of Chengdu, Sichuan province, China. Removal of the PICC at the end of the treatment course was difficult but successfully achieved following the application of our “AFGP” bundle approach, which might be used for difficult PICC removal in extremely preterm infants.

The case events occurred 27 min after premature birth.

Female baby A, weighing 1070 g at 27+1 wk of gestational age, was referred to our hospital because of premature birth. She suffered fasting and gastrointestinal decompression. Necrotizing enterocolitis was considered. PICC was applied thereafter to support nutrition on the 19th day after admission.

After obtaining signed informed consent from the patients’ parents, nurses qualified for PICC insertion performed the insertion using the 1.9Fr PICC catheter (1.9 Fr, single lumen; Vascu-Picc, medCOMP, Inc., Harleysville, PA, United States). The great saphenous vein of the right lower extremity was used for PICC insertion. The catheter was 25 cm in length, and the insertion length was 21 cm. The midpoint of the line from the right heel to the right knee was measured as the right calf circumference, which was 9.5 cm. The chest radiograph showed that the tip position was in the 8th thoracic vertebra (Figure 1).

The catheter was placed for 22 h. After that time, local skin redness occurred at the puncture site (Figure 2), which was determined to be phlebitis level 1 by the visual infusion phlebitis score[12]. To resolve this issue, right lower extremity immobilization was performed, resulting in no obvious improvement.

On the second day after the catheter placement, the area of redness of the skin at the puncture site increased to about 0.2 cm × 5 cm in size and was accompanied by tenderness and the right leg circumference (same measure position as before) that increased to 9.8 cm (Figure 3). Then the polysulfate mucopolysaccharide (Hiliato) was applied to the skin's red zones, which was wrapped in plastic wrap every 4 h for 1 d. However, the redness was not relieved.

On the third day of catheterization, the puncture point presented cordage along the vascular direction with an area of about 0.4 cm × 5 cm that was diagnosed as phlebitis level 2, and the right leg circumference increased to 11 cm (Figure 4). Under these circumstances, the hydrocolloid dressing and the infusion were suspended.

On the fourth day of catheterization, the right leg circumference increased by 2 cm compared with the tube placement, and the popliteal part showed more red swelling covering an area of about 1.5 cm × 4 cm (Figure 5), which was diagnosed as phlebitis level 3. According to guidelines, the PICC should only be replaced on clinical indications, i.e. clinical infection +/– purulence at the insertion site[13]; however, considering the severe complications of PICC and the treatment plan of the baby, we decided to remove it. Yet, the infant started cried during the tube removal, and the catheter rebounded and could not be pulled out. Consequently, the removal was immediately stopped.

At the 40th h after admission, the baby underwent the first PICC insertion through the left upper limb's basilic vein. According to the doctor’s plan, the PICC catheter was pulled out after 17 d.

A female diamniotic-dichorionic twin was delivered by cesarean section at 27+1 wk gestational age to a gravida 1 para 1 mother. Pregnancy was complicated by severe preeclampsia, incomplete HELLP syndrome, mild anemia, dichorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy, etc. The infant’s Apgar scores at 1, 5 and 10 min were 8, 10, and 10, respectively.

A manifestation of prematurity, poor responsiveness, nasal flaring, grunting, and general skin cyanosis.

On the 15th day of admission, the stool examination showed the following: Erythrocyte 5-10/HP, pyocyte-positive, occult blood-positives stool. Abdominal plain film examination showed extensive gas accumulation in the abdominal intestine, no dilatation, and gas accumulation in the intestinal wall.

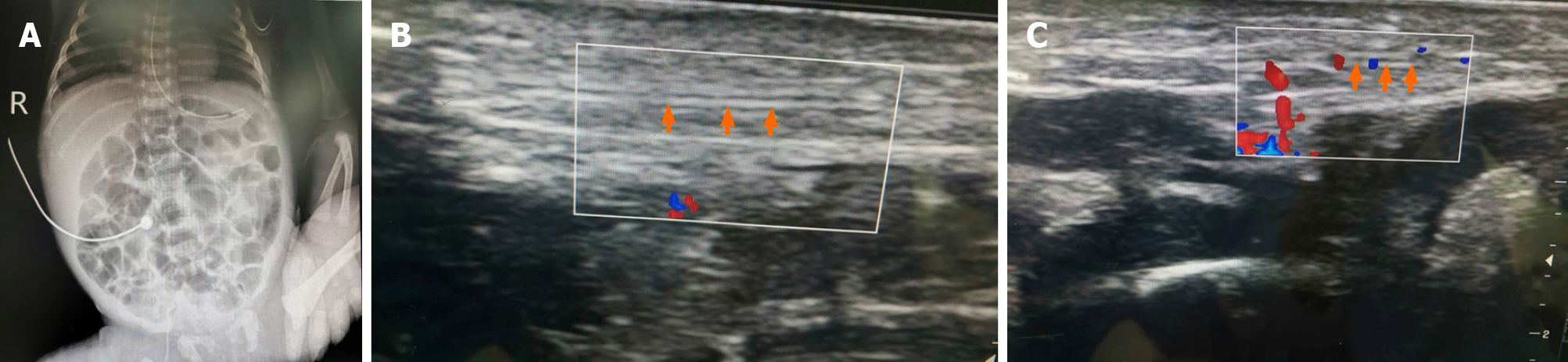

On the day of PICC insertion, the chest radiograph showed that the tip position was in the 8th thoracic vertebra (Figure 1). On the day of PICC removal, the chest radiograph showed that the PICC tip was located on the lower edge of the 10th thoracic vertebra (Figure 6A). Color Doppler mode ultrasound showed that the PICC catheter was intact, the tip was in the inferior vena cava, no venous blood flowed in the blood vessels below the thigh, and the surrounding tissue was disordered (Figure 6B). After trying our “AFGP” bundle for removal of the PICC, the ultrasound revealed that the blood vessels below the thighs were dilated, and there was a little venous blood flow (Figure 6C).

Extremely preterm infant; extremely low birth weight infant; neonatal respiratory distress syndrome.

The patient was treated with “AFGP” bundle.

First, an assessment of the difficult PICC removal was made, and considering that there was an elastic retraction, the level of difficult PICC removal was defined as level 3.

Second, Color Doppler mode ultrasound and X-ray chest were used for identifying the reasons for difficult PICC removal. In this case, we adopted the multidisciplinary teamwork, and invited the ultrasound, radiation, and medical specialists, as well as therapeutic teams, to collaborate. According to the chest radiograph, the PICC tip was located on the lower edge of the 10th thoracic vertebra (Figure 6A). Color Doppler mode ultrasound showed that the PICC catheter was intact, the tip was in the inferior vena cava, no venous blood flowed in the blood vessels below the thigh, and the surrounding tissue was disordered (Figure 6B). So, the malposition of the PICC tip was excluded. Combined with the manifestations of local pain, redness, edema, venous cord-like changes, as well as induration in the upper part of the puncture site and the ultrasound results of this infant, it was decided that the difficult extubation was caused by phlebitis level 3. In children with phlebitis, pain can occur when the catheter is pulled out, which may make them cry. Meanwhile, pain excites the sympathetic nerve, causes vasospasm and vasoconstriction, which in turn leads to difficult extubation.

Third, we tried many general methods to resolve this difficult problem. The baby was allowed to rest for 30 min after the first extubation[14], after which the second extubation was tried, during which there was still resistance. After adjusting the position of the baby by properly stretching the right lower limb, the third extubation was tried[15]. However, the difficulty of extubation was not reduced. After that, during the extubation interval, a saline solution was used for warm, moist compresses for 20 min; nonetheless, PICC still could not be pulled out.

Finally, we choose phentolamine for warm, moist application every 4 h. At 20 h after using phentolamine, the infant's leg circumference was reduced. The ultrasound, which was taken again at the bedside, revealed that the blood vessels below the thighs were dilated, and there was a little venous blood flow (Figure 6C). At this point, after another discussion, the multidisciplinary teamwork decided to try again to extubate, the PICC catheter was finally pulled out. The process of extubation went smoothly, the catheter was intact, and the fibrin sheath was not found. After extubation, the polysulfonic acid mucopolysaccharide ointment was continued to be applied for external use.

At 20 h after using phentolamine for warm and moist compress, we successfully removed the PICC, after which the infant's leg circumference was reduced. After removing the PICC for 42 h, the baby recovered from phlebitis (Figure 7).

On the 36th day of admission, the baby fully recovered and was discharged. Her conditions were re-checked 1 m and 16 d after discharge; no abnormal findings were found on the physical examination.

The vast majority of PICCs can be removed by simple withdrawal. Nonetheless, difficult PICC removal rarely occurs, and when it does, it is usually due to one of these multiple factors: Venous vasospasm, knotting, entanglement, adhesion to venous endothelium, thrombus, and fibrin formation around the catheter[9].

Liang et al[16] reported that the difficulty of PICC extubation was based on four reasons including vasospasm and contraction, drug stimulation, fibrin sheath and thrombosis, and catheter malposition. Venous vasospasm is the most common reason for the difficult extubation of PICC.

Color Doppler mode ultrasound can be used to help identify reasons for difficult PICC removal since it can detect changes in venous hemodynamics, identify vascular stenosis, stenosis of the lumen, and the presence or absence of occlusion[17]. Color Doppler mode ultrasound can also determine the location and size of thrombosis, as well as monitor the thrombosis after extubation and thrombus treatment. In addition, Zhan et al[18] also reported that once the children experience difficult extubation, an ultrasound should be performed for screening so as to clarify whether there was an adherent PICC[18].

In the present case, difficult PICC removal was caused by venous vasospasm caused by phlebitis level 3. Phlebitis is one of the common complications of indwelling PICC[19], which is associated with improper selection of blood vessels and catheters, low puncture position, poor vascular condition, excessive limb movement, damage to the intima at the site of puncture, rapid infusion highly irritating high-concentration drugs, low patient immunity, and similar[20]. The above factors could cause vascular endothelial proliferation, venous valve inflammation, swelling, and stenosis caused by venous lumen, resulting in a sense of resistance during extubation. In this case, the risk factors of phlebitis were as follows: Low puncture site; hyperactive lower limbs; a history of using total parenteral nutrition; and small veins due to being extremely preterm.

At present, there are some methods for resolving difficult PICC removal. However, since these methods are generally aimed toward adults or children, they were not fit for our case, and by trying them, we would risk potentially inflicting severe adverse effects. The surgical approach, for example, was too invasive for such an extreme preterm. Consequently, we needed to identify a non-invasive method to remove the difficult PICC suitable for a newborn, especially an extremely preterm.

When resistance occurs during the process of extubation, it should be immediately stopped, and the reasons for difficult PICC removal should be assessed[16]. Previous studies suggest that patients should rest for 20 to 30 min or longer before extubation[14], which we tried but did not achieve satisfactory results.

Adjusting the position is also considered as a non-invasive intervention for removal. Zhang et al[15] reported that if the position is improper, both the tube and arm position could be adjusted, after which the tube should be retested. This approach also did not provide satisfactory results in the present case.

Warm and moist compress is a common method used to resolve the difficult PICC removal induced by intense vasospasm. In the pediatric population, Le’s study showed that intense vasospasm occurs when the tunica media layer is stimulated during catheter removal and manifests as a palpable cord[9]. This resistance to PICC removal can be treated with heat application to the upper extremity. If this provides no results, catheter removal is delayed by 12-24 h to allow the vasospasm to subside[9]. Warm and moist compress is a hyperthermia method with strong penetrating power and a good effect on deep tissue diathermy. It could dilate blood vessels and promote blood circulation. At the same time, hot compress could reduce the excitability of pain nerves and relieve the stimulation and compression of nerve endings, thereby reducing the stimulation of the blood vessels by the catheter[21]. Ding et al[22] reported that patients could also be given a hot drink, while 50 mL of warm saline could be injected into the catheter to relieve vasospasm. In the present case, a warm saline solution was used for warm, moist compresses over the vein for 20 min, which failed to provide results.

Vasodilatation with a topical glycery trinitrate patch proximal to the insertion site has also been used for difficult PICC removal[11]. While Nitroglycerin can dilate vascular, the Nitroglycerin Ointment is contraindicated in children younger than 18-years-old. Therefore, we chose another vasodilator known as phentolamine, which can reduce peripheral vascular resistance and can be used in children. Finally, we successfully removed the PICC after using phentolamine for warm, moist compresses over the vein every 4 h until 20 h.

In addition, another study reported on a novel endovascular technique for the removal of a tightly adherent PICC[9]. The technique involves passing a mandril through the lumen of the PICC and placing a 6 French sheath. However, this approach is too expensive; thus, we did not try it in the present case.

The surgical approach is used for removal as a final method. In their study, Miall et al[11] reported that among 8 patients with pancreatic cystic fibrosis who had difficulty in extubation of PICC catheters, 2 underwent successful surgical removal. Nonetheless, in the present case, considering the child's condition, it was questionable whether the child could tolerate surgery.

Our results highlight interventions that could be used in neonates suffering from difficult PICC removal. We summarized our approach as “AFGP” bundle: A (Assessment): Initially, an assessment of the difficult PICC removal was made; F (Finding reasons): Color Doppler mode ultrasound and X-ray chest were used to identify reasons causing the difficult PICC removal; G (General nursing): General nursing approaches were used to solve the issue such as putting the baby to rest, adjusting the position of the baby, using the saline solution for warm and moist compress; P (Phentolamine): phentolamine can be used for warm, moist compress for newborns.

Ongoing vigilance for PICC complications is essential, as we do not yet know what happens when PICC is removed. The intervening on complications related to PICC is also of utmost importance. Although this case report has some limitations, such as selection bias and similar, it provides useful advice on how to handle neonates with severe difficult PICC removal.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kotzampassi K S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Wu XJ, Xu B, Zheng YN, Zhao LF, Sun WY, He LX, Luo YL, Cui L, Yang HY, Zhao RY, Hu LJ, Meng AF, Cao J, Yao L. Nursing practice standards for intravenous therapy People's Republic of China Health Industry Standard, 2013 [cited February 20, 2020]. Available from: https://www.docin.com/p-825980661.html. |

| 2. | Schults JA, Kleidon T, Petsky HL, Stone R, Schoutrop J, Ullman AJ. Peripherally inserted central catheter design and material for reducing catheter failure and complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:CD013366. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | National association of neonatal nurses. Peripherally inserted central catheters: guideline for practice [cited February 20, 2020]. Available from: http://hummingbirdmed.com/wp-content/uploads/NANN15_PICC_Guidelines_FINAL.pdf. |

| 4. | Chopra V, O'Horo JC, Rogers MA, Maki DG, Safdar N. The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:908-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream infection, venous thrombosis, and peripherally inserted central catheters: reappraising the evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125:733-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Long BX. Analysis and nursing of related factors of PICC extubation difficulty in patients with cancer. Jilin Yixue Zazhi. 2010;53:110-111. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Wall JL, Kierstead VL. Peripherally inserted central catheters: resistance to removal: a rare complication. J Intraven Nurs. 1995;18:251-254. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Krein SL, Saint S, Trautner BW, Kuhn L, Colozzi J, Ratz D, Lescinskas E, Chopra V. Patient-reported complications related to peripherally inserted central catheters: a multicentre prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:574-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Le J, Grigorian A, Chen S, Kuo IJ, Fujitani RM, Kabutey NK. Novel endovascular technique for removal of adherent PICC. J Vasc Access. 2016;17:e153-e155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chemaly RF, de Parres JB, Rehm SJ, Adal KA, Lisgaris MV, Katz-Scott DS, Curtas S, Gordon SM, Steiger E, Olin J, Longworth DL. Venous thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a retrospective analysis of the Cleveland Clinic experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1179-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Miall LS, Das A, Brownlee KG, Conway SP. Peripherally inserted central catheters in children with cystic fibrosis. Eight cases of difficult removal. J Infus Nurs. 2001;24:297-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alexander M. Infusion therapy standards of practice. J Infus Nurs. 2016;39:S79-S80. |

| 13. | Queensland Government. Guideline: Peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICC) [cited February 20, 2020], 2015. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0032/444497/icare-picc-guideline.pdf. |

| 14. | Schwengel DA, McGready J, Berenholtz SM, Kozlowski LJ, Nichols DG, Yaster M. Peripherally inserted central catheters: a randomized, controlled, prospective trial in pediatric surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1038-1043, table of contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang MY, Wu HJ, Hu QY. Nursing care of patients with peripheral venous catheter with difficulty in extubation. Huli Yu Kangfu Zazhi. 2009;8:779-780. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Liang M, He JA. Related factors of PICC extubation difficulties and current status of coping strategies. Qilu Huli Zazhi. 2014;19:58-61. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Zhao LS, Wang SM, Zhao L, Hao CL. Effect of Ultrasonography on PICC Extubation Process. Zhonghua Chaosheng Yixue Zazhi. 2016;32:1140-1142. |

| 18. | Zhan S, Xue XY. Nursing report on the difficulty of PICC extubation in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Shiyong Linchuang Hulixue Dianzi Zazhi. 2018;3:167-171. |

| 19. | Litz CN, Tropf JG, Danielson PD, Chandler NM. The idle central venous catheter in the NICU: When should it be removed? J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:1414-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang L, Lu YL, Si LJ, Chang Y. Cause analysis and prevention of PICC complications. Hushi Peixun Zazhi. 2007;22:75-77. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Lu YF, Lin JX, Wang XZ. Nursing care of patients with mechanical phlebitis after PICC operation. Hushi Jinxiu Zazhi. 2008;23: 48-49. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Ding XP, Xia CL, Li HM, Liu J, Li WJ. Using peripherally inserted central catheter among hemopathic patients undergoing chemotherapy. Zhonghua Huli Zazhi. 2006;41:415-416. |