Published online Jun 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4166

Peer-review started: March 8, 2021

First decision: March 27, 2021

Revised: April 5, 2021

Accepted: April 20, 2021

Article in press: April 20, 2021

Published online: June 16, 2021

Processing time: 78 Days and 20.2 Hours

Needle-knife fistulotomy (NKF) is used as a rescue technique for difficult cannulation. However, the data are limited regarding the use of NKF for primary biliary cannulation, especially when performed by beginners.

To assess the effectiveness and safety of primary NKF for biliary cannulation, and the role of the endoscopist’s expertise level (beginner vs expert).

We retrospectively evaluated the records of 542 patients with naïve prominent bulging papilla and no history of pancreatitis, who underwent bile duct cannulation at a tertiary referral center. The patients were categorized according to the endoscopist’s expertise level and the technique used for bile duct cannula

The baseline characteristics did not differ between the experienced and less-experienced endoscopists. The incidence rate of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) was significantly affected by the endoscopist’s expertise level in patients who received conventional cannulation with sphincterotomy (8.9% vs 3.4% for beginner vs expert, P = 0.039), but not in those who received NKF. In the multivariable analysis, a lower expertise level of the biliary endoscopist (P = 0.037) and longer total procedure time (P = 0.026) were significant risk factor of PEP in patients who received conventional cannulation with sphincterotomy but only total procedure time (P = 0.004) was significant risk factor of PEP in those who received NKF.

Primary NKF was effective and safe in patients with prominent and bulging ampulla, even when performed by less-experienced endoscopist. We need to confirm which level of endoscopist’s experience is needed for primary NKF through prospective randomized study.

Core Tip: Needle-knife fistulotomy (NKF) is used as a rescue technique for difficult cannulation. However, the data are limited regarding the use of NKF for primary biliary cannulation, especially when performed by beginners. Our retrospective study aims to assess the effectiveness and safety of primary NKF for biliary cannulation, and the role of the endoscopist’s expertise. The incidence rate of post-endoscopic retrog

- Citation: Han SY, Baek DH, Kim DU, Park CJ, Park YJ, Lee MW, Song GA. Primary needle-knife fistulotomy for preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: Importance of the endoscopist’s expertise level. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(17): 4166-4177

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i17/4166.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4166

Needle-knife fistulotomy (NKF) is used as a rescue technique when cannulation is difficult[1]. Many studies have reported the effectiveness and safety of early precut NKF for preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP). In particular, precut NKF was reported to be associated with a higher rate of successful cannulation and lower incidence of PEP than conventional cannulation techniques[2-6]. Recently, randomized controlled trial study on NKF has been published, proved the safety and efficacy of primary NKF in high-risk cohort of PEP[7]. Despite these encouraging reports, NKF has not been adopted as a primary cannulation technique because most endoscopists believe that a high level of experience is required in order to achieve a sufficiently high rate of successful cannulation and an acceptable rate of adverse events with a use of primary NKF in patients with naïve papilla. Several previous studies on the effectiveness and safety of early NKF reported that NKF procedures performed by less experienced or experienced endoscopists provided comparable rates of adverse events[8,9]. However, there are no published data regarding the level of expertise that is needed for achieving the effectiveness and safety of NKF for primary biliary cannulation.

It is of utmost importance to minimize the risk of PEP, which is difficult to control and potentially lethal even in cases handled by expert biliary endoscopists. Other life-threatening adverse events related to NKF, such as perforation and bleeding, have become relatively manageable due to the continuous developments in instrumentation (especially covered metallic stent, endoclips and absorbable hemostatic powder) and radiologic interventions (e.g., angiographic embolization). However, there are only few study about that the safety of primary NKF for achieving bile duct access in patients with naïve papilla[10]. Furthermore, it is necessary to compare how many manageable adverse events occur between beginners and experts when performed NKF vs conventional cannulation for primary biliary cannulation in patients with naïve papilla.

We aimed to assess the effectiveness and safety of primary NKF according to expertise level of endoscopists in patients with naïve papilla undergoing bile duct cannulation.

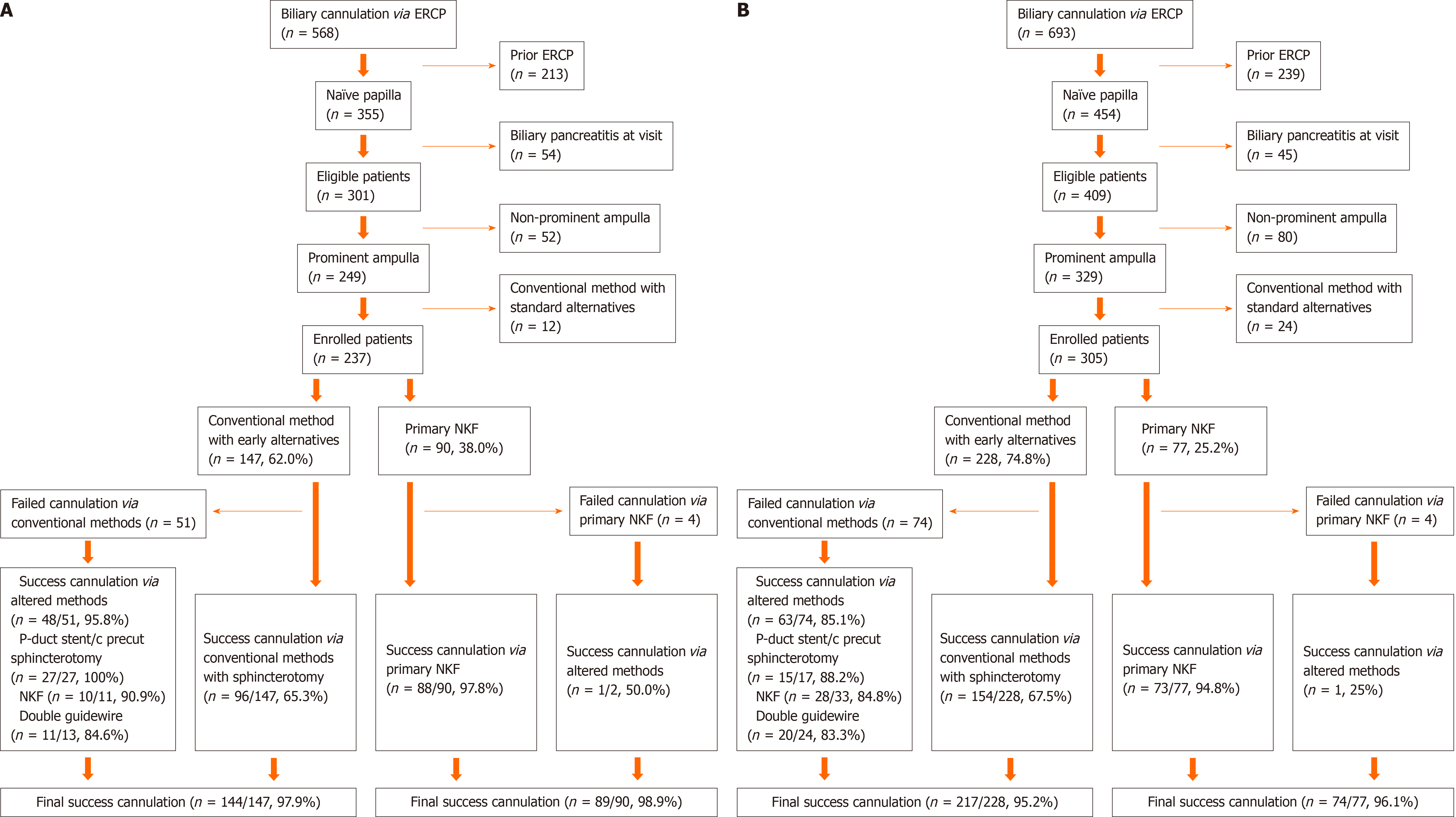

Among the patients who received ERCP at our hospital, we identified 568 patients who were managed by an expert (over 3000 ERCP procedures) as well as 693 patients managed by a beginner (over 500 ERCP observations with an assistance and then over 300 ERCP procedures with supervision of an expert) between April 2014 and March 2016. The beginner was trained by the expert for a year prior to dispatch. We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of candidates and excluded patients who underwent previous ERCP or presented with biliary pancreatitis at admission. Patients who did not change to altered method even in difficult cannulation were also excluded. And we also excluded patients with non-prominent ampulla, because, they were not suitable for NKF. Finally, 542 patients with naïve papilla (expert, 237; beginner, 305) were enrolled in this study to analyze the effectiveness and safety of primary biliary cannulation, as well as to clarify the role of the endoscopist’s expertise level (Figure 1). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2013) and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of our Hospital (H-1805-023-067).

The patients were stratified according to the endoscopist’s expertise level (beginner vs expert) and according to the primary cannulation technique employed (conventional cannulation vs NKF). Among the 237 patients managed by the expert, 147 underwent conventional cannulation using a guidewire-assisted technique, while 90 underwent NKF. Among the 305 patients managed by the beginner, 228 received conventional cannulation and 77 received NKF.

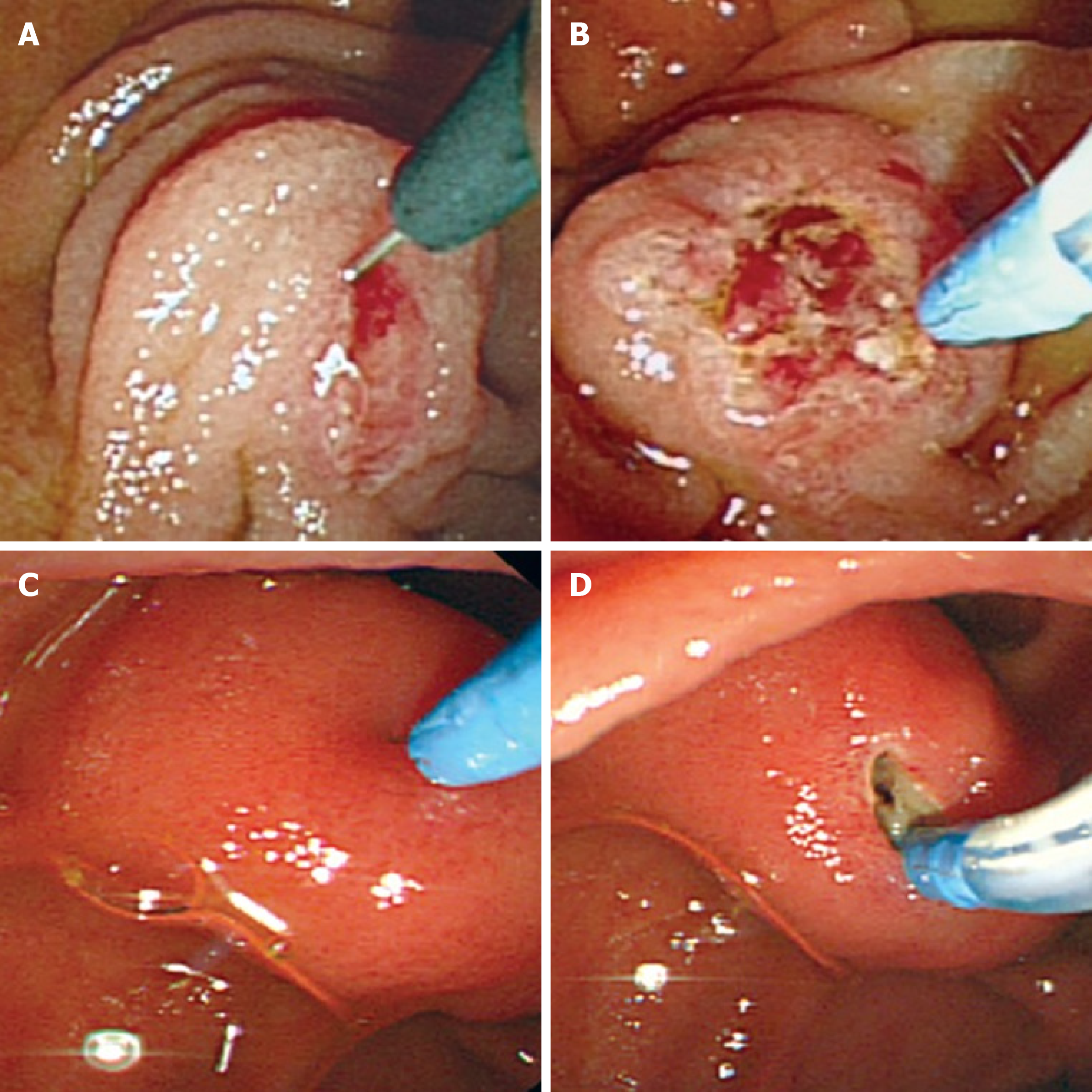

Conventional cannulation was conducted by using a guidewire-assisted technique with various guidewires (Jagwire from Boston scientific, MA, United States; Terumo from Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan; and Visiglide from Olympus Co.). The catheter impacts in the papilla before attempting to advance the guidewire for cannulation. If the ampullary orifice was probed > 5 times or > 5 min had passed without achieving biliary access; more than one unintended pancreatic duct cannulation or opacification, we switched to another technique such as pancreatic guidewire-assisted biliary cannulation, pancreatic duct stent placement followed by precut sphincterotomy, or NKF. However, as the study was retrospective in design, the time taken to change to the rescue method was not exactly equal in all cases but was constant. Prophylactic pancreatic stenting was attempted when there was pancreatic duct contrast injection or over twice of pancreatic duct cannulations. Sphincterotomy was performed in all patients. Patients who were performed ERCP without sphincterotomy were not enrolled. In precut sphincterotomy, the needle-knife (Boston scientific, MA, United States) was initially placed at the orifice of the ampulla and the incision was made in an upward direction between the 11 and 12 o'clock positions. In precut NKF, the orifice of the ampulla of Vater remained without contact. The needle-knife as used to initially make a mucosal incision at the maximal bulging point of the papillary roof of the ampulla and then cut the oral side of papillary muscle at the 11-12 o’clock position[12] (Figure 2). In order to reduce the risk of perforation, the needle was kept short with minimal incision of whitish papillary muscles until the red mucosa of bile duct or bile was visualized. After biliary cannulations, additional sphincterotomy was not required for biliary stenting after biopsy or small stone removal, but additional sphincterotomy or endoscopic balloon dilatation was required to remove large stones.

We evaluated the initial and final cannulation success rates, cannulation time, total procedure time, and ERCP-related adverse events in each group (expert vs beginner; conventional cannulation with sphincterotomy vs NKF). The effectiveness and safety of NKF for primary biliary cannulation were established based on the outcomes noted in patients managed by the expert.

Procedural success was defined as selective cannulation in a single ERCP session. Cannulation time was calculated from the first probing of the ampullary orifice until selective bile duct cannulation. Total procedure time was calculated from the first probing of the ampullary orifice until the end of the procedure. Our institution has some rules that during the ERCP procedure, we must capture the photo (confirmation of ampulla, after succeeding of cannulation, end of procedure). These pictures can be used to estimate cannulation time and total procedure time.

We monitored for PEP by measuring serum amylase and lipase levels before and at 24 h after the procedure. Abdominal radiography was performed to check for perforation 4 h after the procedure in patients with abdominal pain after procedure. ERCP-related adverse events were defined as bleeding, PEP, and perforation, the severity of which was classified according to the Cotton criteria[11]. Hyperamylasemia was defined as high amylase levels without abdominal pain or signs of pancreatitis.

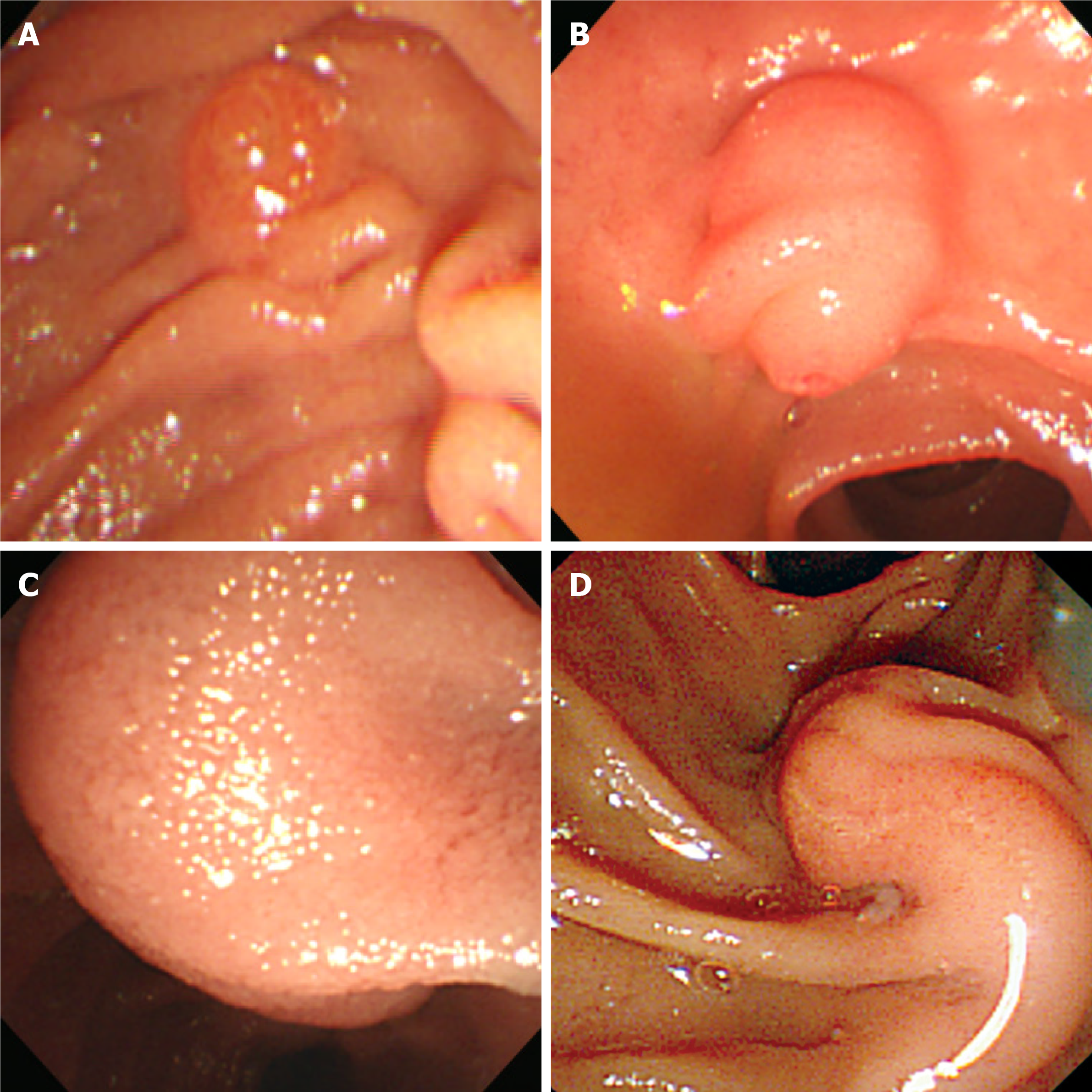

Non-prominent ampulla was defined as a small papilla without marked oral protrusion. And bulging of the ampulla was defined as a marked swelling from the bulge in the papillary roof to the oral ridge of the duodenal wall[12]. The information that was including procedure method, outcome parameter were retrospectively reviewed by a third biliary endoscopist.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistical software, version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States). Baseline characteristics, procedural characteristics, and outcomes were compared between the groups that were defined based on the endoscopist’s expertise level (expert vs beginner) and cannulation technique (conventional cannulation vs NKF). Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify the predictors of PEP. In multivariable analysis, logistic regres

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 542 patients included in the study are summarized in Table 1 (ampulla configurations[12] were shown in Figure 3). The two groups defined based on the endoscopist’s expertise level did not differ signific

| Total, n = 542, (%) | Experienced, n = 237, (%) | Less-experienced, n = 305, (%) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 67.8 ± 13.4 | 66.6 ± 14.2 | 68.7 ± 12.6 | 0.070 |

| Male (%) | 307 (56.6) | 129 (54.4) | 178 (58.4) | 0.361 |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 163 (30.1) | 81 (34.2) | 82 (26.9) | 0.067 |

| Ampulla configurations | 0.224 | |||

| Non-prominent | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Prominent | 455 (83.9) | 205 (86.5) | 250 (82.0) | |

| Bulging | 65 (12.0) | 25 (10.5) | 0 (13.1) | |

| Distorted | 15 (2.8) | 3 (1.3) | 12 (3.9) | |

| Hook-nose shape | 7 (1.3) | 4 (1.7) | 3 (1.0) | |

| Malignancy | 200 (36.9) | 91 (38.4) | 109 (35.7) | 0.525 |

| Benign diseases | 342 (63.1) | 146 (61.6) | 196 (64.3) |

| Conventional technique with sphincterotomy, n = 375, (%) | Primary NKF less-experienced, n = 167, (%) | |||||

| Experienced, n = 147, (%) | Less-experienced, n = 228, (%) | P value | Experienced, n = 90, (%) | Less-experienced, n = 77, (%) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 68.8 ± 12.9 | 68.7 ± 12.1 | 0.964 | 63.1 ± 15.6 | 68.7 ± 14.3 | |

| Male | 75 (51.0) | 130 (57.0) | 0.256 | 54 (60.0) | 48 (62.3) | 0.759 |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 52 (35.4) | 68 (29.8) | 0.262 | 29 (32.2) | 14 (18.2) | 0.039a |

| Ampulla configurations | 0.625 | 0.265 | ||||

| Non-prominent | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Prominent | 136 (92.5) | 205 (89.9) | 69 (76.7) | 54 (70.1) | ||

| Bulging | 8 (5.4) | 19 (8.3) | 17 (18.9) | 16 (20.8) | ||

| Distorted | 2 (1.4) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (6.50) | ||

| Hook-nose shape | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.6) | ||

| Malignancy | 58 (39.5) | 80 (35.1) | 0.393 | 33 (36.7) | 29 (37.7) | 0.895 |

| Benign diseases | 89 (60.5) | 148 (64.9) | 57 (63.3) | 48 (62.3) | ||

The results of the comparison between the groups defined according to the endoscopist’s expertise level are summarized in Table 3. Among the patients who underwent NKF, the expertise level was not associated with any significant differences in outcomes, including PEP incidence rate, procedural success rate, except cannulation time (4.2 min vs 5.5 min, P=0.010). However, among patients who underwent conventional cannulation with sphincterotomy, the PEP rate was significantly lower in patients managed by the expert than in those managed by the beginner (3.4% vs 8.9%, P = 0.039). Generally, the incidence rate of adverse events (PEP, hyperamylasemia, bleeding and perforation) was lower among patients managed by the expert.

| Conventional technique with sphincterotomy | NKF | |||||

| Experienced (n = 147) (%) | Less-experienced (n = 228) (%) | P value | Experienced (n = 90) (%) | Less-experienced (n = 77) (%) | P value | |

| Success rate | 361/375 (96.3) | 161/167 (96.4) | 0.936 | |||

| 144/147 (98.0) | 217/228 (95.2) | 0.166 | 88/90 (97.8) | 73/77 (94.8) | 0.306 | |

| Cannulation time (min) | 4.8 ± 3.5 | 4.8 ± 3.2 | 0.951 | |||

| 5.1 ± 3.5 | 4.6 ± 3.6 | 0.200 | 4.2 ± 3.1 | 5.5 ± 3.1 | 0.010a | |

| Total procedure time (min) | 17.2 ± 9.2 | 15.2 ± 8.2 | 0.019a | |||

| 17.6 ± 9.6 | 16.9 ± 8.9 | 0.490 | 14.9 ± 8.4 | 15.6 ± 8.0 | 0.598 | |

| Post-ERCP pancreatitis | 25 (6.7) | 4 (2.4) | 0.040a | |||

| 5 (3.4) | 20 (8.9) | 0.039a | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.9) | 0.243 | |

| Hyperamylasemia | 52 (14.0) | 13 (7.8) | 0.041a | |||

| 15 (10.2) | 37 (16.4) | 0.090 | 5 (5.6) | 9 (11.7) | 0.156 | |

| Bleeding | 10 (2.7) | 6 (3.6) | 0.568 | |||

| 2 (1.4) | 8 (3.6) | 0.202 | 2 (2.2) | 4 (5.2) | 0.306 | |

| Perforation | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.505 | |||

| 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.423 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | |

Among the 542 patients with naïve papilla who underwent ERCP and presented with no pancreatitis at admission, a total of 29 developed PEP. In the univariate analysis, the endoscopist’s expertise level and total procedure time were significantly associated with PEP incidence in patients who underwent conventional cannulation, whereas the cannulation time and total procedure time were significantly associated with PEP incidence in patients who underwent NKF. In the multivariate analysis, the endoscopist’s expertise level (P = 0.037) and total procedure time (P = 0.026) were the independent predictor significantly associated with PEP incidence in patients who underwent conventional cannulation, whereas a longer total procedure time (P = 0.004) was associated with PEP occurrence in patients who underwent NKF (Table 4).

| Conventional technique with sphincterotomy | NKF | |||||||||||

| Total | With PEP | Without PEP | P value | Odd ratio (95%CI) | Total | With PEP | Without PEP | P value | Odd ratio (95%CI) | |||

| n = 375, (%) | n = 25, (%) | n = 350, (%) | Uni- | Multi- | n = 167, (%) | n = 4, (%) | n = 163, (%) | Uni- | Multi- | |||

| Age (yr) | 68.7 ± 12.4 | 65.6 ± 12.5 | 69.0 ± 12.4 | 0.194 | 0.126 | 0.98(0.94-1.01) | 65.7 ± 15.3 | 69.8 ± 11.9 | 65.6 ± 15.3 | 0.593 | - | |

| Male (%) | 205 (54.7) | 12 (48.0) | 193 (55.1) | 0.490 | 102 (61.1) | 2 (50.0) | 100 (61.3) | 0.648 | - | |||

| Periampullary diverticulum | 120 (32.0) | 8 (32.0) | 112 (32.0) | 0.999 | 43 (25.7) | 1 (25.0) | 42 (25.8) | 0.973 | - | |||

| Malignancy | 138 (36.8) | 9 (36.0) | 129 (36.9) | 0.932 | 62 (37.1) | 3 (75.0) | 59 (36.2) | 0.114 | 0.165 | 4.74(0.41-54.8) | ||

| Benign diseases | 237 (63.2) | 16 (64.0) | 221 (63.1) | - | 105 (62.9) | 1 (25.0) | 104 (63.8) | - | - | |||

| Less-experienced endoscopist | 228 (60.8) | 20 (80.0) | 208 (59.4) | 0.044a | 0.037a | 2.94(1.07-8.10) | 77 (46.1) | 3 (75.0) | 74 (45.4) | 0.243 | 0.110 | 6.40 (0.45-90.6) |

| Pancreatic duct stent | 72 (19.2) | 4 (16.0) | 68 (19.4) | 0.675 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | |||

| Cannulation time (min) | 4.8 ± 3.5 | 5.3 ± 3.5 | 4.7 ± 3.5 | 0.431 | 4.8 ± 3.2 | 8.8 ± 1.7 | 4.7 ± 3.1 | 0.010a | 0.945 | 0.99 (0.75-1.31) | ||

| Total procedure time (min) | 17.2 ± 9.2 | 21.0 ± 8.8 | 16.9 ± 9.2 | 0.031a | 0.026a | 1.04 (1.01-1.08) | 15.2 ± 8.2 | 30.0 ± 9.3 | 14.8 ± 7.9 | 0.000a | 0.004a | 1.14 (1.04-1.25) |

Early NKF has been confirmed as a highly successful rescue procedure in cases with difficult bile duct access, being associated with low PEP incidence[9,13-15]. Furthermore, it has been observed that the incidence rates of severe bleeding and perforation are similar between NKF and conventional cannulation with sphincterotomy. However, primary NKF continues to be considered a high-risk procedure in patients with naïve papilla.

In our study, the incidence rate of PEP was significantly higher in patients managed by the beginner than in those managed by the expert endoscopist, although there was no significant difference in the final rate of successful cannulation (Supplementary Table 1). However, the endoscopist’s expertise level did not influence the PEP rate in patients who received NKF. Few studies have been published regarding the impact of the endoscopist’s experience level on NKF outcomes. Lee et al[9] reported that an endoscopist with experience of > 100 ERCPs, including > 10 precut procedures, can perform NKF efficiently and safely. In our study, the beginner had observed and assisted > 500 ERCP procedures, and then performed > 300 ERCP procedures with the supervision of an expert. Based on the European guidelines regarding papillary cannulation[16], NKF should be performed only by endoscopists who achieve successful biliary cannulation in > 80% of cases. A single-operator learning curve analysis for biliary cannulation suggested that procedural success rates of > 80% can be obtained after > 350 supervised ERCP procedures[17]. Taken together, these previous findings and our present results suggest that it is acceptable to perform NKF after > 500 ERCP observations with an assistance and then > 300 ERCP procedures with the supervision of an expert.

In our study, the incidence rates of PEP (8.3% vs 2.4%, P = 0.010) and hyperamylasemia (15.6% vs 8.4%, P = 0.023) was significantly lower in patients who received NKF than in those who received conventional cannulation, even though the rates of other serious adverse events did not differ. A recent study reported that in comparison to delayed NKF, early NKF was associated with a significantly lower PEP inciden

We had no standard criteria for the selection of the cannulation technique. However, the morphology of the infundibulum was an important factor in the decision to try primary NKF. Specifically, if the infundibulum is large and covers the papilla, it is difficult to approach the ampullary orifice, and thus, NKF is expected to provide better results because it facilitates access to the bile duct at a site distinct from the ampullary orifice. The expert frequently performed primary NKF procedures in patients who had large infundibula. If the patients had a small ampulla without an infundibulum, primary NKF was not performed. If the infundibulum extended beyond the field of view, a catheter was used to remove the air from the duodenum and probe the duodenal wall in order to evaluate the extent of the infundibulum. If a retracted ampulla or small ampulla was identified, conventional methods were used instead of NKF. In such ampulla, NKF is not considered suitable due to complications such as perforation. Primary NKF was preferred in patients with PEP risk factors such as non-dilated bile duct (< 9 mm)[18], low serum levels of total bilirubin, and young age, which is why the age was lower in patients who received NKF than in those who received conventional cannulation.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study, and the effect of selection bias could not be excluded. Second, the number of NKF procedures performed by the beginner was not uniformly distributed along the study period. Moreover, the PEP incidence was higher in the first half of the study period, when the beginner performed mostly conventional cannulation with sphincterotomy. Third, there was no definitive criteria for primary NKF. On the other hand, the present study enrolled a relatively large cohort of patients who received primary NKF. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the outcomes of primary NKF according to the endoscopist’s expertise level.

Our findings suggest that PEP risk is not associated with the endoscopist’s expertise level in cases of primary NKF. Therefore, we recommend primary NKF as an effective and safe method for achieving ductal access in patients with prominent and bulging infundibulum, and may be especially useful for beginners because, compared to conventional cannulation with sphincterotomy, NKF is less likely to induce PEP due to insufficient expertise of the endoscopist. Further prospective studies are warranted to validate our present results.

Needle-knife fistulotomy (NKF) is used as a rescue technique for difficult cannulation.

However, the data are limited regarding the use of NKF for primary biliary cannula

To assess the effectiveness and safety of primary NKF for biliary cannulation, and the role of the endoscopist’s expertise.

To evaluate the records of 542 patients with naïve prominent bulging papilla and no history of pancreatitis, who underwent bile duct cannulation at a tertiary referral center.

The incidence rate of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis was significantly affected by the endoscopist’s expertise level in patients who received conventional cannulation with sphincterotomy, but not in those who received NKF.

Primary NKF may be effective and safe in achieving ductal access in patients with naïve papilla, regardless of experience.

Primary NKF as an effective and safe method for achieving ductal access in patients with prominent and bulging infundibulum, and may be especially useful for beginners.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Matsubara S S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Mariani A, Di Leo M, Giardullo N, Giussani A, Marini M, Buffoli F, Cipolletta L, Radaelli F, Ravelli P, Lombardi G, D'Onofrio V, Macchiarelli R, Iiritano E, Le Grazie M, Pantaleo G, Testoni PA. Early precut sphincterotomy for difficult biliary access to reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2016;48:530-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen J, Wan JH, Wu DY, Shu WQ, Xia L, Lu NH. Assessing Quality of Precut Sphincterotomy in Patients With Difficult Biliary Access: An Updated Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52:573-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tang Z, Yang Y, Yang Z, Meng W, Li X. Early precut sphincterotomy does not increase the risk of adverse events for patients with difficult biliary access: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sundaralingam P, Masson P, Bourke MJ. Early Precut Sphincterotomy Does Not Increase Risk During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Patients With Difficult Biliary Access: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 1722-1729. e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Navaneethan U, Konjeti R, Venkatesh PG, Sanaka MR, Parsi MA. Early precut sphincterotomy and the risk of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography related complications: An updated meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:200-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Ceroni L, Laterza L, Fabbri C, Bazzoli F. Can early precut implementation reduce endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related complication risk? Endoscopy. 2010;42:381-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Jang SI, Kim DU, Cho JH, Jeong S, Park JS, Lee DH, Kwon CI, Koh DH, Park SW, Lee TH, Lee HS. Primary Needle-Knife Fistulotomy Versus Conventional Cannulation Method in a High-Risk Cohort of Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:616-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jin YJ, Jeong S, Lee DH. Utility of needle-knife fistulotomy as an initial method of biliary cannulation to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in a highly selected at-risk group: a single-arm prospective feasibility study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:808-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee TH, Bang BW, Park SH, Jeong S, Lee DH, Kim SJ. Precut fistulotomy for difficult biliary cannulation: is it a risky preference in relation to the experience of an endoscopist? Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1896-1903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Khatibian M, Sotoudehmanesh R, Ali-Asgari A, Movahedi Z, Kolahdoozan S. Needle-knife fistulotomy vs standard method for cannulation of common bile duct: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Iran Med. 2008;11:16-20. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2038] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Lee TH, Park SH, Yang JK, Han SJ, Park S, Choi HJ, Lee YN, Cha SW, Moon JH, Cho YD. Is the Isolated-Tip Needle-Knife Precut as Effective as Conventional Precut Fistulotomy in Difficult Biliary Cannulation? Gut Liver. 2018;12:597-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gong B, Hao L, Bie L, Sun B, Wang M. Does precut technique improve selective bile duct cannulation or increase post-ERCP pancreatitis rate? Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2670-2680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kaffes AJ, Sriram PV, Rao GV, Santosh D, Reddy DN. Early institution of pre-cutting for difficult biliary cannulation: a prospective study comparing conventional vs. a modified technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:669-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Testoni PA, Mariani A, Aabakken L, Arvanitakis M, Bories E, Costamagna G, Devière J, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Dumonceau JM, Giovannini M, Gyokeres T, Hafner M, Halttunen J, Hassan C, Lopes L, Papanikolaou IS, Tham TC, Tringali A, van Hooft J, Williams EJ. Papillary cannulation and sphincterotomy techniques at ERCP: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2016;48:657-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Verma D, Gostout CJ, Petersen BT, Levy MJ, Baron TH, Adler DG. Establishing a true assessment of endoscopic competence in ERCP during training and beyond: a single-operator learning curve for deep biliary cannulation in patients with native papillary anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:394-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Elmunzer BJ, Mariani A, Meister T, Deviere J, Marek T, Baron TH, Hassan C, Testoni PA, Kapral C; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - updated June 2014. Endoscopy. 2014;46:799-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |