Published online May 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3779

Peer-review started: January 10, 2021

First decision: February 12, 2021

Revised: February 16, 2021

Accepted: March 4, 2021

Article in press: March 4, 2021

Published online: May 26, 2021

Processing time: 121 Days and 8.1 Hours

Scleritis is a rare disease and the incidence of bilateral posterior scleritis is even rarer. Unfortunately, misdiagnosis of the latter is common due to its insidious onset, atypical symptoms, and varied manifestations. We report here a case of bilateral posterior scleritis that presented with acute eye pain and intraocular hypertension, and was initially misdiagnosed as acute primary angle closure. Expanding the literature on such cases will not only increase physicians’ awareness but also help to improve accurate diagnosis.

A 53-year-old man was referred to our hospital to address a 4-d history of bilateral acute eye pain, headache, and loss of vision, after initial presentation to a local hospital 3 d prior. Our initial examination revealed bilateral cornea edema accompanied by a shallow anterior chamber and visual acuity reduction, with left-eye amblyopia (> 30 years). There was bilateral hypertension (by intraocular pressure: 28 mmHg in right, 34 mmHg in left) and normal fundi. Accordingly, acute primary angle closure was diagnosed. Miotics and ocular hypotensive drugs were prescribed, but the symptoms continued to worsen over the 3-d treatment course. Further imaging examinations (i.e., anterior segment photography and ultrasonography) indicated a diagnosis of bilateral posterior scleritis. Methylprednisolone, topical atropine, and steroid eye drops were prescribed along with intraocular pressure-lowering agents. Subsequent optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed gradual improvements in subretinal fluid under the sensory retina, thickened sclera, and ciliary body detachment.

Bilateral posterior scleritis can lead to secondary acute angle closure. Diagnosis requires ophthalmic accessory examinations (i.e., ultrasound biomicroscopy, B-scan, and OCT).

Core Tip: Bilateral scleritis is the rarest form of scleritis. The clinical presentation is quite variable, which can make diagnosis even more difficult. Among all cases of scleritis, the overall frequency of intraocular hypertension is low, at only 12.6%. Moreover, among that subpopulation of scleritis cases, bilateral involvement with shallow anterior chamber is often misdiagnosed as uveitis (especially, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome) and acute primary angle-closure glaucoma. Differential diagnosis is essential for accurate and effective treatment. We report here a case of bilateral posterior scleritis with acute eye pain and intraocular hypertension, initially misdiagnosed as acute primary angel closure.

- Citation: Wen C, Duan H. Bilateral posterior scleritis presenting as acute primary angle closure: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(15): 3779-3786

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i15/3779.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3779

Scleritis is a relatively unusual condition arising from cellular derangement, with the characteristic features of immune-cell infiltration, collagen degradation, and vascular remodeling of the sclera tissue observable by advanced imaging examinations. The typical physical manifestations that prompt sufferers to seek medical care are relatively nonspecific, including eye pain, decreased visual acuity, and dull headache. The combined presentations of the anatomical situation and symptom profile underlie the classification of this condition as anterior or posterior scleritis[1]. In regard to the incidence, only about 1/3 of posterior scleritis cases are bilateral, highlighting the extreme rarity of this subtype of scleritis.

The clinical presentation of bilateral posterior scleritis is very diverse, further complicating diagnosis[2]. The versatile clinical signs of posterior scleritis include retinal striae, fluid accumulation under the retina (which leads to retinal detachment), retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) folds, optic disk edema, and choroidal thickening[3]. Among all cases of scleritis, the overall frequency of intraocular hypertension is low (12.6%[1]). Moreover, among these secondary intraocular hypertension patients, cases of bilateral involvement with shallow anterior chamber are often misdiagnosed as uveitis [especially, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome] and acute primary angle-closure glaucoma. Differential diagnosis is essential because the treatment of these conditions is completely different.

A 53-year-old man was referred to our hospital to address complaints of bilateral acute eye pain, headache, and loss of vision that had lasted for 4 d.

Three days prior to presentation at our hospital, the patient visited a local hospital with the same complaints and was diagnosed with bilateral acute primary angle closure, bilateral refractive error, and amblyopia in his left eye. He was prescribed pilocarpine eye drops (4 times/daily), carteolol hydrochloride (2 times/daily), brinzolamide (3 times/daily), and oral acetazolamide tablets (2 times/daily). The doctors also recommended consideration of laser peripheral iridectomy. However, after 3 d of the drug regimen, the patient’s symptoms only continued to worsen.

At admission, the patient reported no history of systemic immunologic disease, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus. He denied a recent history of influenza infection and of any signs of neurological disorders. Excluding poor eyesight in the left eye, he denied any diagnoses of ocular disorders or refractive error.

The patient denied any diagnoses of personal and family history.

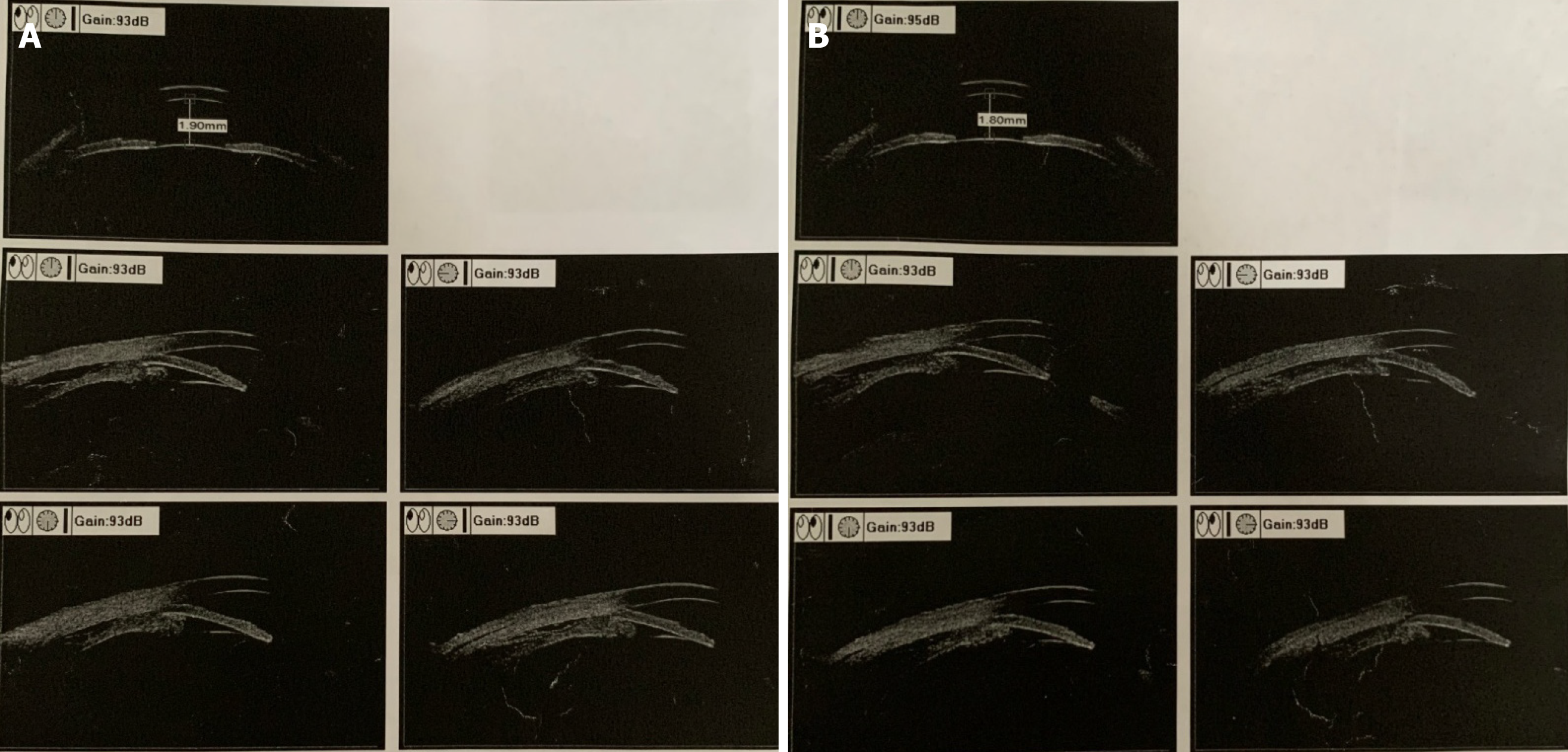

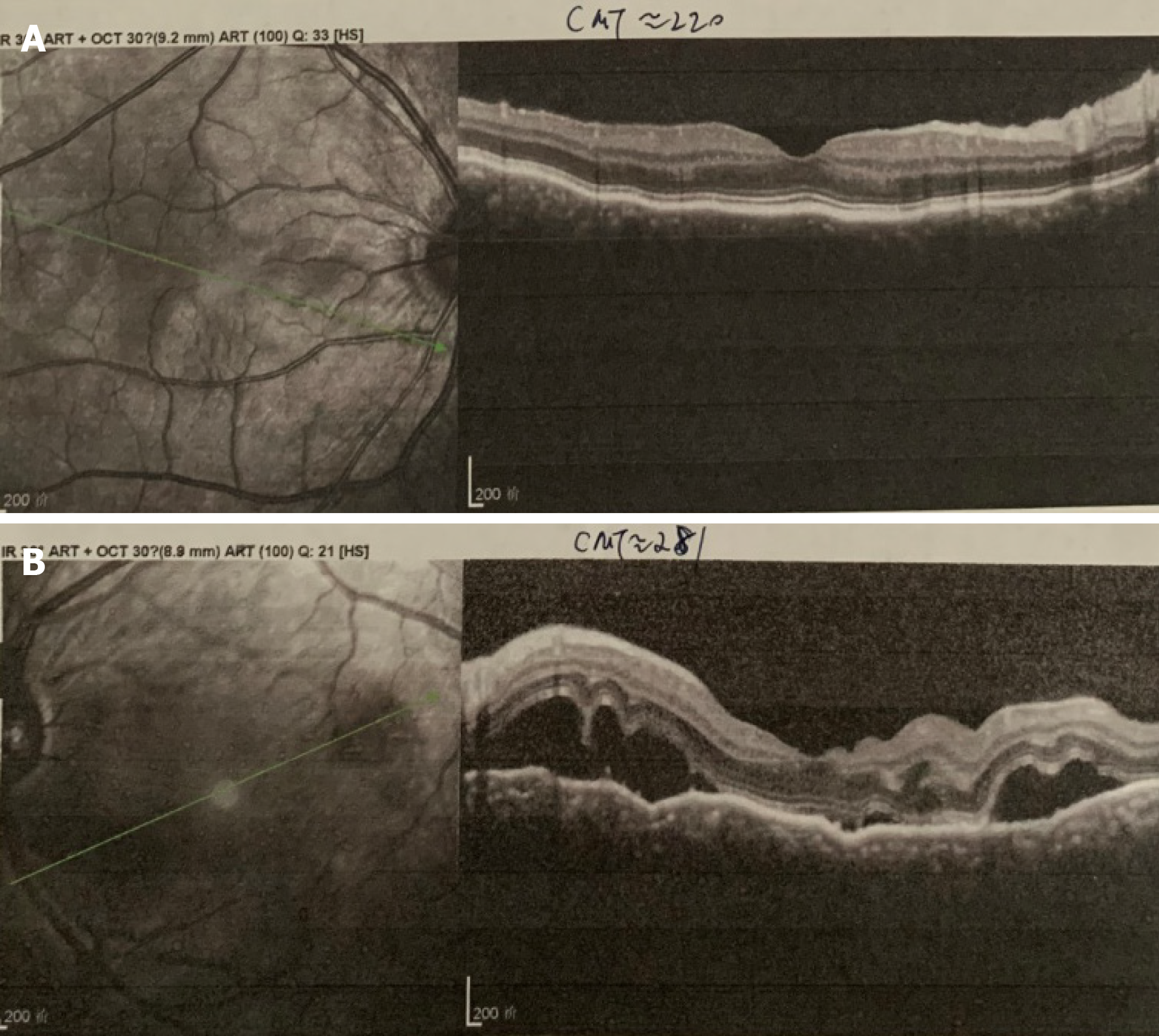

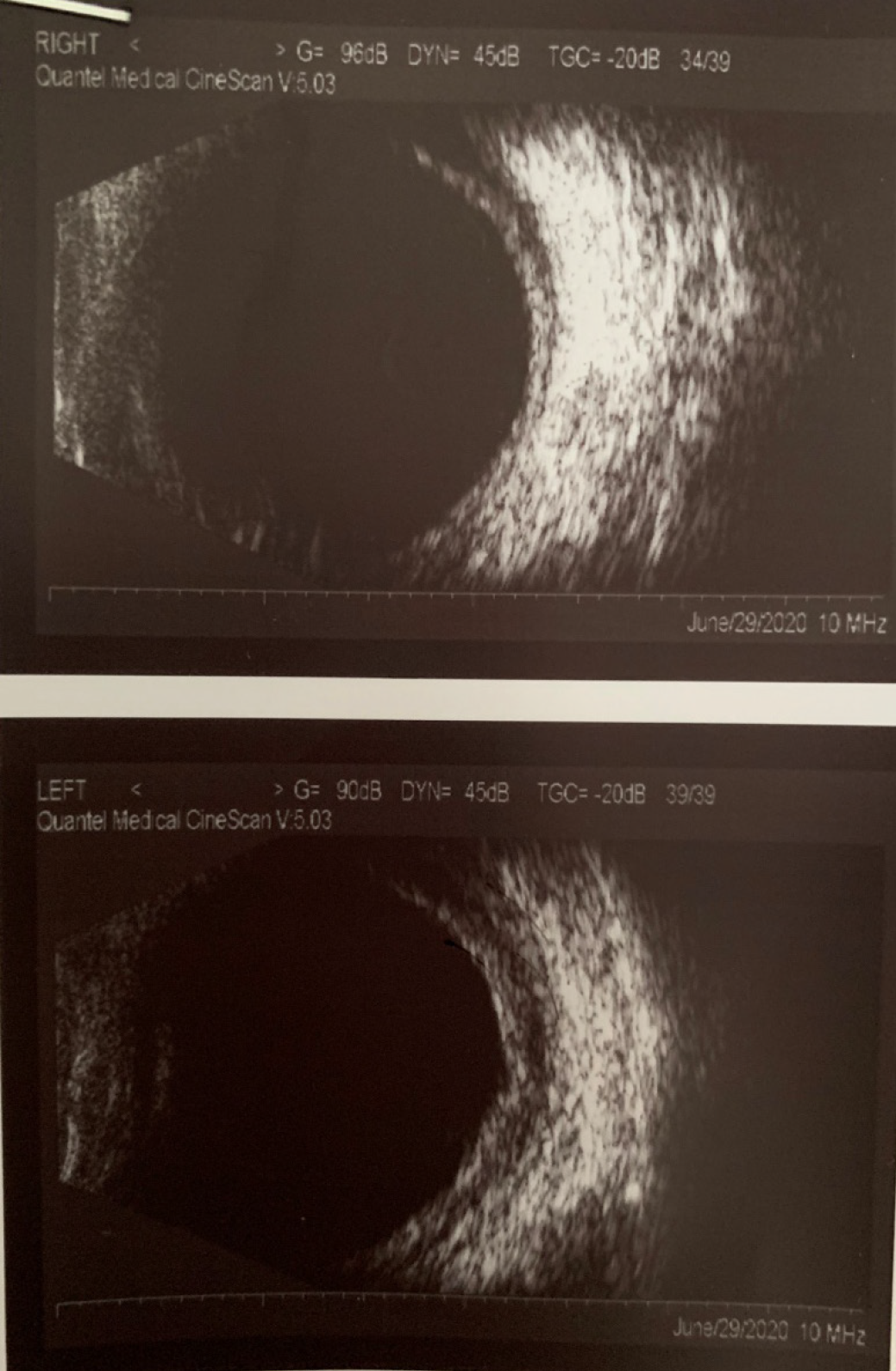

Physical examination showed cornea edema accompanied by a shallow anterior chamber in both eyes. Best corrected visual acuity was a reduction to 0.6 (corrected by -1.5 Ds) in the right eye and 0.2 (not correctable) in the left eye. Both pupils were round but with slight dilation, situated in front of a transparent lens. Both eyes showed hypertension, with intraocular pressure (IOP) of 32 mmHg for the right eye and 38mmHg for the left eye. Ultrasound biomicroscopic (UBM) examination showed that the anterior chamber depth of the right eye was 1.9 mm and of the left was 1.8mm; in addition, cyclodialysis, pronated ciliary process, and totally closed anterior chamber angle were observed. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) examination showed RPE folds in the right eye and optic disc edema and multiple serous retinal detachments in the left eye. Ultrasound examination showed bilateral thickening of the posterior wall (2.6 mm in the right eye and 2.7 mm in the left eye) and fluid under Tenon’s capsule.

Laboratory examinations included tests for complete blood count and sedimentation rate, levels of C-reactive protein, serum rheumatoid factor, and angiotensin converting enzyme, titer of anti-streptolysin O, and presence of serum anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and antinuclear antibody (commonly referred to as ANA). All results were within normal ranges.

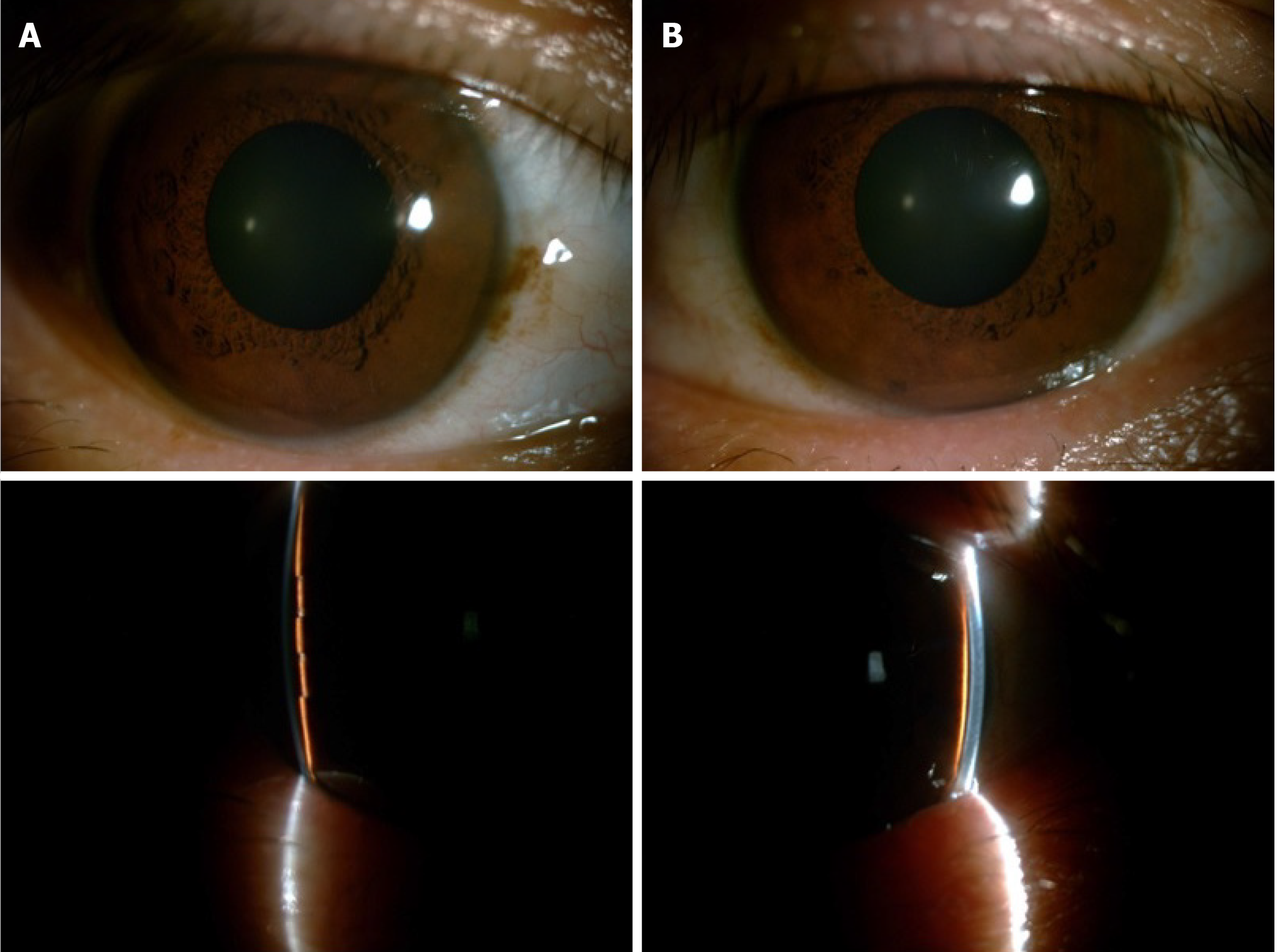

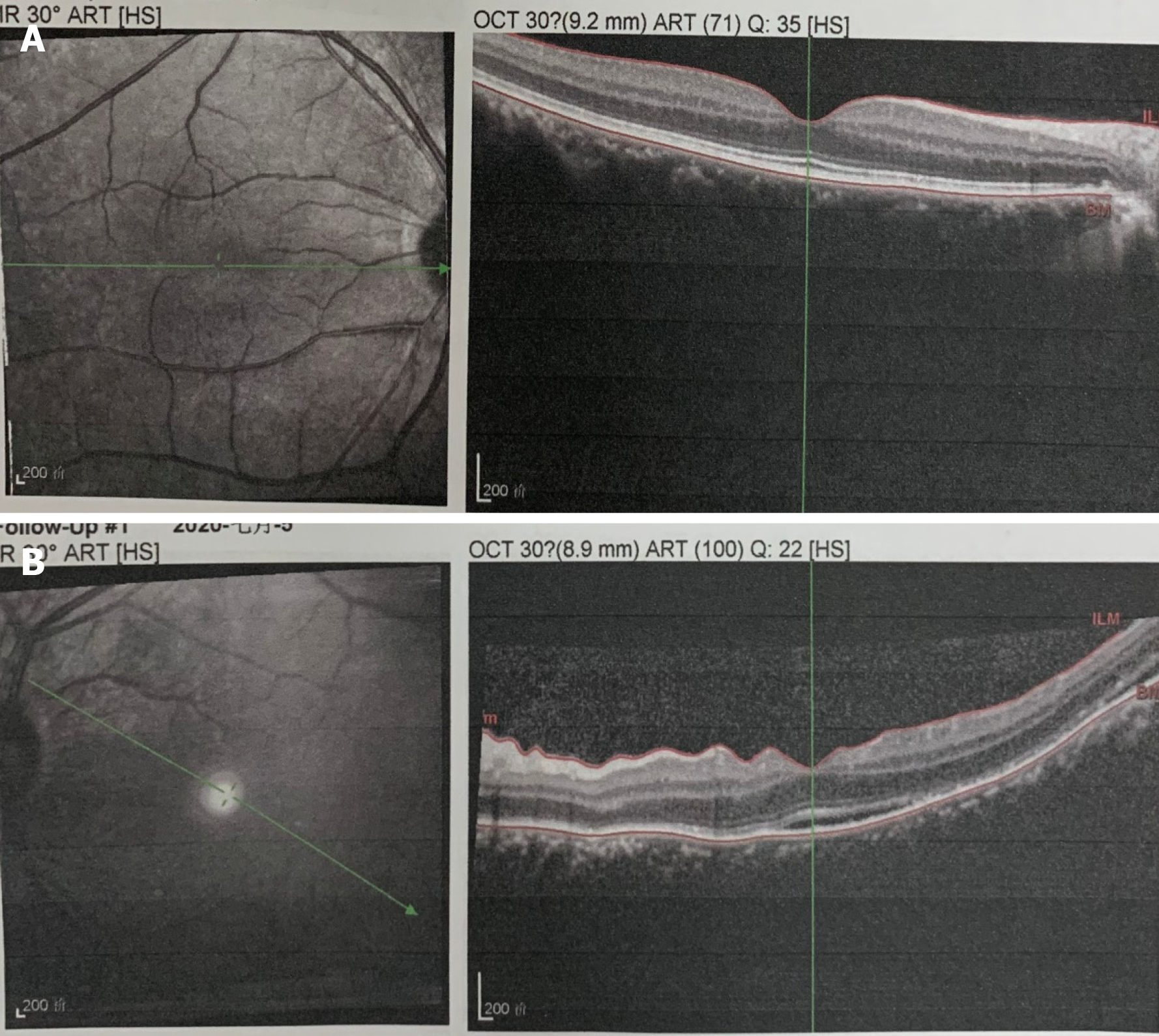

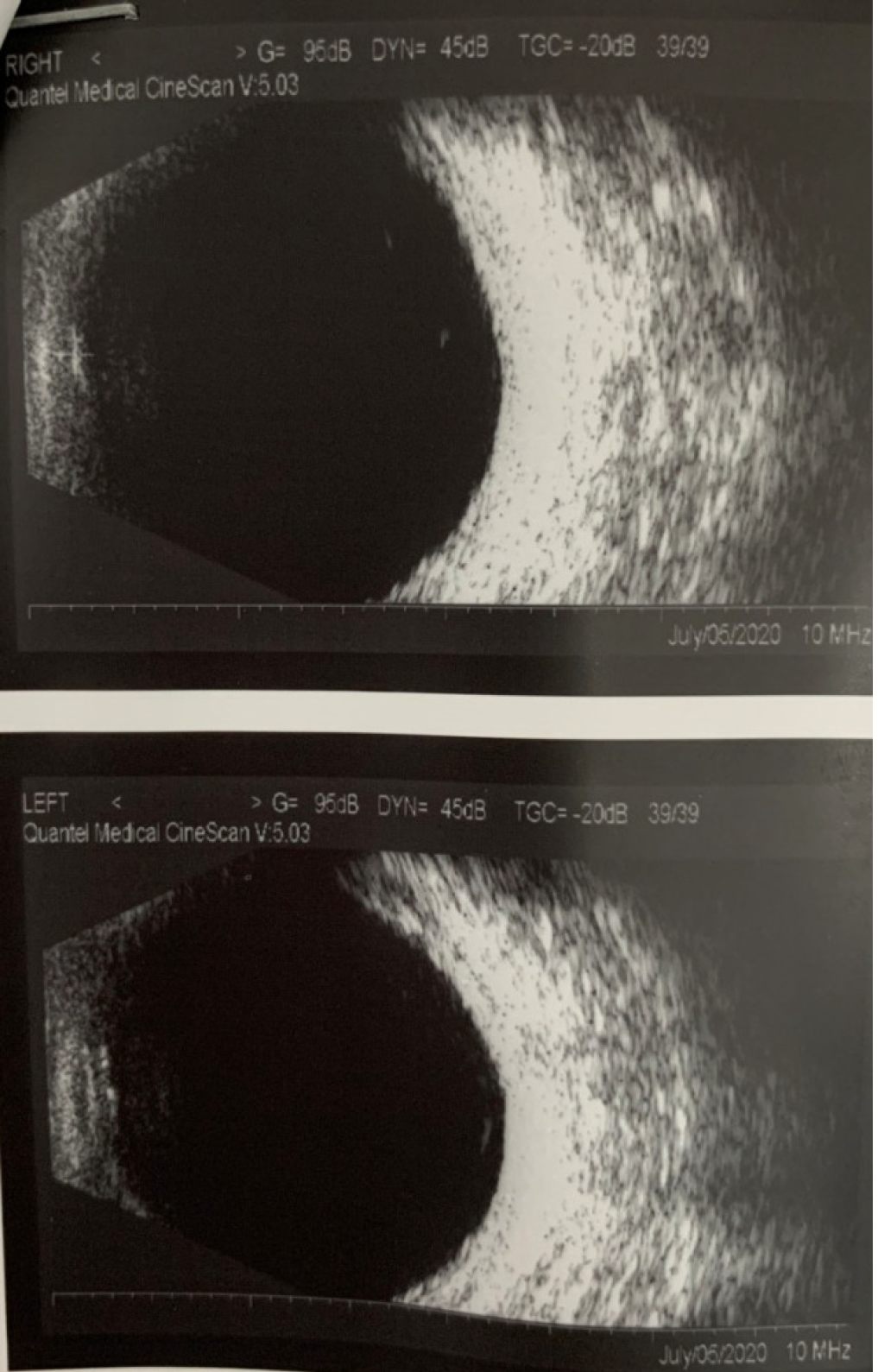

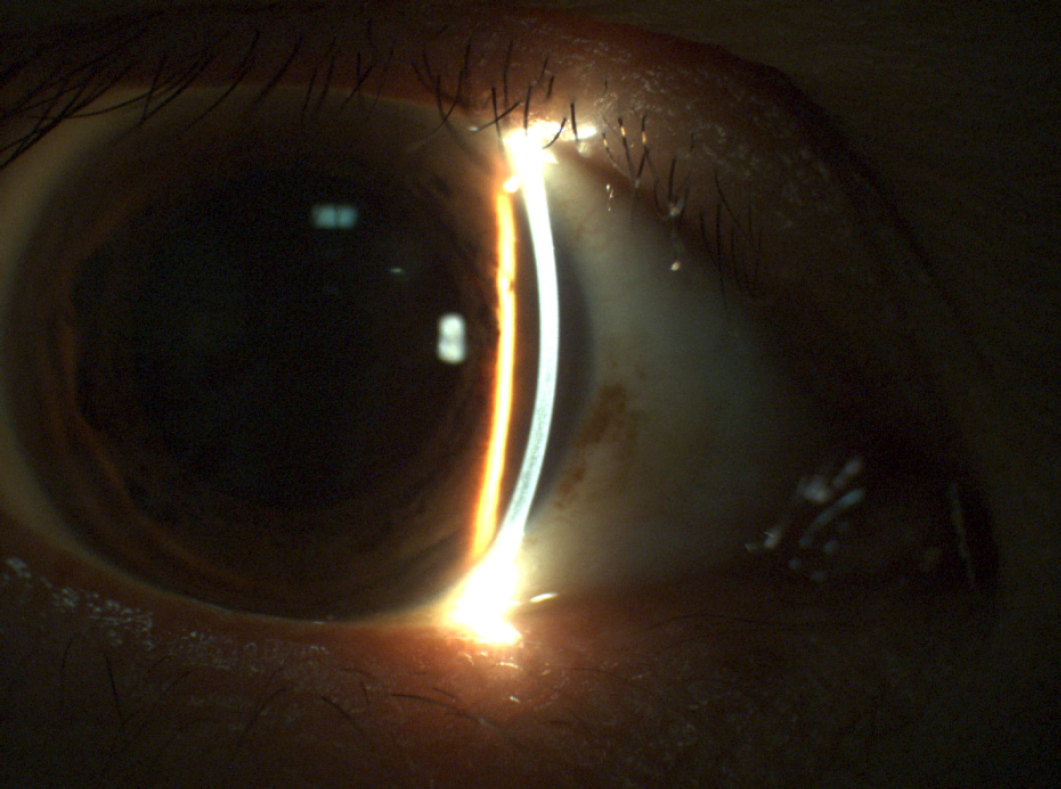

Anterior segment photography revealed a quite shallow anterior chamber accompanied by mild cornea edema in both eyes. The pupils were 5 mm and symmetrical to each other. Lenses were transparent without dislocation (Figure 1A and B). Measurement of the anterior chamber depths by UBM also revealed cyclodialysis, pronated ciliary process, and total closure of the anterior chamber angle in both eyes (Figure 2A and B). OCT showed RPE folds in the right eye and optic disc edema and multiple serous retinal detachments in the left eye (Figure 3A and B). Ultrasound showed thickening of the posterior walls and presence of fluid under Tenon’s capsule in both eyes (Figure 4).

Bilateral posterior scleritis

The patient was prescribed oral methylprednisolone (50 mg/d) on a tapered reduction schedule, as well as calcium tablets, potassium chloride tablets, and omeprazole (20 mg/d) to counter the side effects of steroid treatment. Atropine sulfate eye ointment (1 time/daily) and 0.1% fluorometholone eye drops (4 times/daily) along with carteolol hydrochloride (2 times/daily), brinzolamide (3 times/daily), and oral methazolamide (100 mg/d) were prescribed to decrease the ocular hypertension.

After 1 wk of this treatment regimen, the patient’s symptoms started to improve, prompting a reduction in the oral methylprednisolone drug on day 11 of treatment (to 30 mg/d); at the same time, the topical eye drops and ointment treatments were withdrawn. B-scan ultrasound examination at 1.5 mo gave normal findings, at which point the methylprednisolone was stopped.

OCT examination carried out after the 1st week of treatment showed that the RPE folds and serous detachment had resolved (Figure 5A and B). At that time, B-scan ultrasound also showed resolution of the cyclodialysis and thinning of the posterior walls (Figure 6A and B). Slit-lamp examination showed deepening of the anterior chamber and both pupils to become dilated upon application of atropine sulfate eye ointment (Figure 7). Computerized optometric display showed the refractive degrees to be +1.5 Ds and +6.5 Ds, after adjustment relaxation, in the right eye and left eye, respectively.

As of the writing of this manuscript, the patient attends monthly follow-up visits and his visual acuity has remained stable at normal.

Posterior scleritis is a relatively uncommon and frequently under-recognized type of scleral disease. According to the literature, the incidence of bilateral posterior scleritis varies by country and region, ranging from as low as 15.78% to as high as 71.40%[4]. The clinical features of bilateral posterior scleritis are similar to those of unilateral cases, although there is a prevalence towards younger age, female sex, and elevated ANA titers[2]. The primary presenting symptoms are red eye, periocular pain, and headache, and the clinical ocular findings at presentation are wide ranging, including congestion, anterior scleritis, serous retinal detachment, papilledema, and/or higher IOP[5].

When ocular hypertension is present in both eyes with an extra-shallow anterior chamber, which is a more common feature in Asians, it is easy to diagnose acute primary angle closure. The latter condition tends to be more usual in elderly people with short axial length[6]. Our patient's ocular axis was 22.6 mm in the right eye and 20.4 mm in the left eye (conforming to his established hyperopia), which is inconsistent with the clinical manifestations of primary angle-closure glaucoma. Our patient's anterior characteristics were more subtle than those for acute-onset primary angle closure and he showed inconspicuous congestion and corneal edema as well as mild dilated but round pupil. Choroid detachment is common after IOP-induced drops in angle-closure glaucoma but the retina seldom detaches under this situation. Our patient had normal fundi at the beginning of our management, which likely supported the initial misdiagnosis at the first hospital that he visited. When he was referred to our hospital, however, his papillary edema and retinal serous detachment had become obvious, which, when considered along with his collective clinical features, inspired us to conduct further examinations to determine the true reason for his symptoms.

VKH syndrome must be part of the differential diagnosis strategy and ruled out in order to make an accurate diagnosis of bilateral posterior scleritis. When the presence of bilateral shallow anterior chambers is accompanied by higher IOP, especially, fundi manifestations can include serous retinal detachment, optic disk swelling, and abnormal findings on fluorescein fundus angiography[7]. Ultrasonography is an essential tool for the diagnosis of posterior scleritis. The “T” sign (present in 41.2% of reported cases[8]) indicates fluid accumulation at the sub-Tenon’s space accompanied by enhancive scleral thickness. Recently, investigations of collective OCT findings revealed that the frequency of subretinal mass was exceedingly more common in acute VKH disease patients (80%) than in patients with posterior scleritis (15%); however, the incidence of RPE folds was higher in posterior scleritis patients (62%) than in acute VKH disease patients (55%)[8]. Our patient showed no signs of iritis in either eye and no signs of predominately neurological and auditory manifestations either. Till now, his fundi have remained stable, without the sunset-glow sign.

The increasing IOP in scleritis patients is affected by many factors. Heinz et al[9]have proposed that secondary glaucoma may be rooted in either obstruction of the trabecular meshwork by inflammatory cells directly, attachment of the peripheral cornea to the iris, or a delayed response due to steroid. Other scholars believe that thickening and inflammation of the sclera increase the difficulty of aqueous humor outflow, and lead to fluid retention in the choroid. In addition to these factors, thicker sclera may oppress vortex veins and hinder the backflow of choroidal veins, which will facilitate choroidal congestion and ciliary body detachment[10]. Our patient's UBM results revealed an annular ciliochoroidal detachment and obvious anterior rotation of the ciliary body, which prompted the lens–iris diaphragm to move forward and the transient angle-closure.

Bilateral posterior scleritis should be among the differential diagnoses of acute primary angle closure, and requires further ophthalmic accessory examinations, such as UBM, B-scan ultrasonography, and OCT.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Ophthalmology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Stratton R S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Yang P, Ye Z, Tang J, Du L, Zhou Q, Qi J, Liang L, Wu L, Wang C, Xu M, Tian Y, Kijlstra A. Clinical Features and Complications of Scleritis in Chinese Patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26:387-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | González-López JJ, Lavric A, Dutta Majumder P, Bansal N, Biswas J, Pavesio C, Agrawal R. Bilateral Posterior Scleritis: Analysis of 18 Cases from a Large Cohort of Posterior Scleritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ando Y, Keino H, Nakayama M, Watanabe T, Okada AA. Clinical Features, Treatment, and Visual Outcomes of Japanese Patients with Posterior Scleritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28:209-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Molina-Prat N, Doctor P, Tauber J, Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS. Clinical features and presentation of posterior scleritis: a report of 31 cases. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22:203-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Erdogan M, Sayin N, YıldızEkinci D, Bayramoglu S. Bilateral Posterior Scleritis Associated with Giant Cell Arteritis: A Case Report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26:1244-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li S, Tang G, Fan SJ, Zhai G, Lv J, Zhang H, Lu W, Jiang J, Lv A, Wang N, Cao K, Zhao J, Vu V, Mu D, Pan X, Feng H, Hsia YC, Han Y. Blindness short after treatment of acute primary angle closure in China. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yuan F, Zhang Y, Yan X. Bilateral acute angle closure glaucoma as an initial presentation of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome: A clinical case report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020: 1120672120951442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu XY, Peng XY, Wang S, You QS, Li YB, Xiao YY, Jonas JB. Features of optical coherence tomography for the diagnosis of vogt-koyanagi-harada disease. Retina. 2016;36:2116-2123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Heinz C, Bograd N, Koch J, Heiligenhaus A. Ocular hypertension and glaucoma incidence in patients with scleritis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:139-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ikeda N, Ikeda T, Nomura C, Mimura O. Ciliochoroidal effusion syndrome associated with posterior scleritis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2007;51:49-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |