Published online May 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3726

Peer-review started: January 6, 2021

First decision: January 24, 2021

Revised: February 2, 2021

Accepted: March 20, 2021

Article in press: March 20, 2021

Published online: May 26, 2021

Processing time: 125 Days and 6.9 Hours

Amebic colitis is an infection caused by Entamoeba histolytica and most commonly observed in regions with poor sanitation. It is also seen as a sexually transmitted disease in developed countries. While amebic colitis usually has a chronic course with repeated exacerbations and remissions, it may also manifest as a fulminant form that rapidly progresses and leads to severe, life-threatening complications, such as intestinal perforation, peritonitis, and sepsis, that have a high mortality rate.

A 68-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with chest pain and acute dyspnea. He was diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome, acute heart failure, and bacterial pneumonia. His respiratory condition worsened despite receiving intensive care and intravenous antibiotics. On the fifth day of hospitalization, he was diagnosed with acute respiratory distress syndrome and was started on steroid therapy. He subsequently developed bloody stools and was diagnosed with cytomegalovirus (CMV) enterocolitis based on biopsy results and a peripheral blood CMV pp65 antigenemia test result. Although we started antiviral therapy with ganciclovir, which was successful in reducing his antigen titers, he continued to have bloody diarrhea. Three weeks after initiation of ganciclovir therapy and six weeks after his admission, the patient died from intestinal perforation. We only posthumously diagnosed him with amebic colitis and CMV enterocolitis based on autopsy findings of transmural necrosis of the entire colon with massive ameba infiltration.

We urge clinicians to consider Entamoeba histolytica infection if severe colitis progresses after steroid therapy. Preemptive treatment is recommended then.

Core Tip: The fulminant form of amebic colitis leads to severe, life-threatening complications such as intestinal perforation, peritonitis, and sepsis. We missed the diagnosis in a patient on steroid therapy who had a positive cytomegalovirus antigen test result. A high index of suspicion for possible Entamoeba histolytica infection is required. This is particularly relevant in patients with severe colitis that progresses after steroid therapy. We recommend preemptive treatment, even without a definite diagnosis, because of the high mortality rate.

- Citation: Shijubou N, Sumi T, Kamada K, Sawai T, Yamada Y, Ikeda T, Nakata H, Mori Y, Chiba H. Fulminant amebic colitis in a patient with concomitant cytomegalovirus infection after systemic steroid therapy: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(15): 3726-3732

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i15/3726.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3726

Amebic colitis is an infection caused by the parasitic protozoan Entamoeba histolytica that is more commonly observed in regions with poor sanitation. There are 40000–74000 annual deaths worldwide due to invasive amebiasis[1]. Amebic colitis also occurs as a sexually transmitted disease in developed countries, with 7763 cases reported from the first week of 2007 to week 43 of 2016 in Japan[2].

Amebic colitis generally follows a chronic course of repeated exacerbations and remissions. In some cases, the fulminant form may progress rapidly and lead to severe, life-threatening complications such as intestinal perforation, peritonitis, and sepsis[3].

We report on a patient with fulminant amebic colitis that was only diagnosed on autopsy. The patient had been mistakenly treated for cytomegalovirus (CMV) enteritis, which developed during steroid pulse therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Clinicians need to be aware of this rare but critical colitis manifestation that is frequently fatal.

A 68-year-old Japanese man (height: 160 cm, weight: 75 kg) was admitted to our hospital with chest pain and acute dyspnea. He worked as a truck driver and had never traveled abroad.

The chest pain and dyspnea had started a few days previously and had worsened over time. The patient had not received treatment prior to admission.

The patient’s medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension that were treated with oral metformin hydrochloride (750 mg daily) and valsartan (80 mg daily), respectively. His diabetes was poorly controlled, with a hemoglobin A1c of 7.7%.

He denied a history of similar diseases in close relatives.

On auscultation, his heart sounds were normal with no murmur. Coarse crackles were heard in both lungs. No other abnormalities were detected.

Laboratory data at the time of admission are shown in Table 1. In summary, his white blood cell count and C-reactive protein levels were high. Myocardial enzymes lactate dehydrogenase and aspartate aminotransferase were elevated, and troponin-T was positive. An anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody test result was negative.

| Hematology | Biochemistry | Serology | |||

| WBC | 16000 cells/μL | Total protein | 7.4 g/dL | CRP | 18.38 mg/dL |

| Neutrophils | 79.0% | Albumin | 3.2 g/dL | Troponin-T | 1.76 ng/mL |

| Lymphocytes | 13.7% | Total bilirubin | 1.1 mg/dL | NT-proBNP | 4526 pg/mL |

| Eosinophils | 0.1% | AST | 137 U/L | Anti-HIV1/2 Ab | Negative |

| RBC | 504 × 104 cells/μL | ALT | 131 U/L | ||

| Hemoglobin | 15.0 g/dL | LDH | 720 U/L | ||

| Hematocrit | 43.8% | ALP | 392 U/L | ||

| Platelets | 36.2 × 104/μL | CK | 348 U/L | ||

| CK-MB | 3.2 ng/mL | ||||

| BUN | 20.5 mg/dL | ||||

| Creatinine | 1.10 mg/dL | ||||

| Na | 132 mEq/L | ||||

| K | 4.3 mEq/L | ||||

| Cl | 97 mEq/L | ||||

| HbA1c (NGSP) | 7.7% | ||||

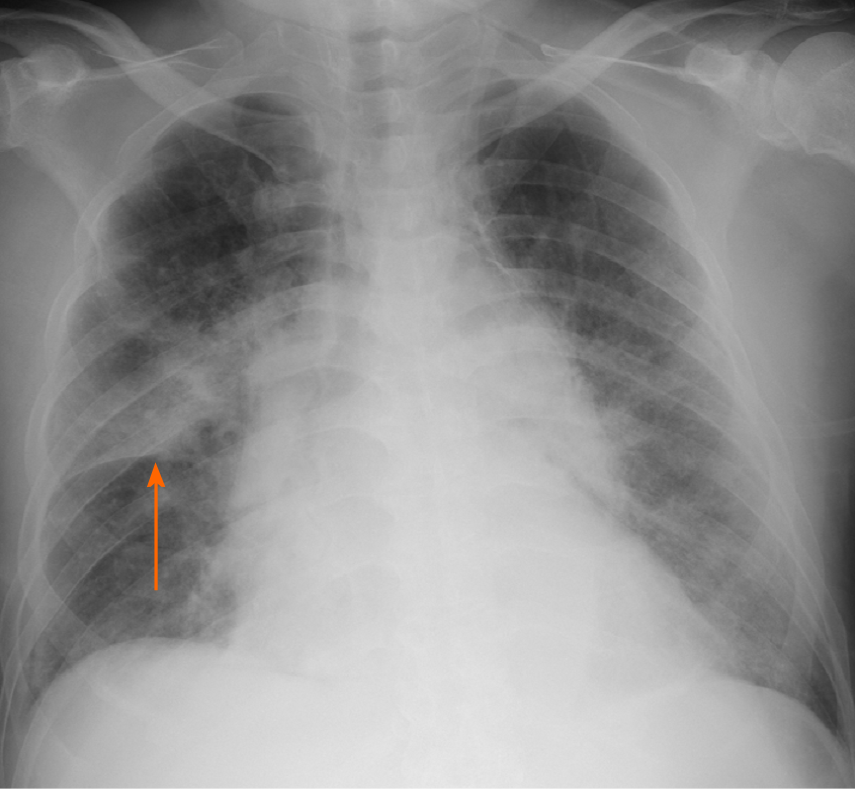

His chest radiography on admission showed consolidation in the right upper lobe and bilateral congestion (Figure 1).

Cardiac infarction and bacterial pneumonia.

The patient immediately underwent percutaneous coronary intervention and was subsequently admitted to the intensive care unit. On admission to the intensive care unit, his oxygen saturation was 92% with a reservoir mask providing 10 L oxygen/min) and his respiratory rate was 30 breaths/min.

He was intubated and started on invasive mechanical ventilation because of progressive respiratory failure. Although he was treated with intravenous antibiotics (levofloxacin 500 mg daily and ampicillin/sulbactam 9 g daily), vasodilators, and diuretics, he developed progressive respiratory failure, even with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 80% and a positive end expiratory pressure of 15 cmH2O under ventilatory control.

On the fifth day of hospitalization, the patient was diagnosed with ARDS. We initiated extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and administered intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g daily for three days. Consecutively, prednisolone 60 mg daily was started to treat the infiltration observed on chest radiography. His respiratory condition subsequently improved by day eight. On the same day, we found blood in the patient’s stool. We attributed this to the dual antiplatelet therapy started after percutaneous coronary intervention and decided to monitor the patient closely.

His condition stabilized, and we were able to discontinue the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on day 10 and extubate him on day 12. His prednisolone dose was tapered to 40 mg daily by day 17, after which his respiratory condition suddenly worsened. The patient had to be re-intubated on day 18, at which time we again started intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g daily for three days. His respiratory condition improved, and prednisolone was reduced to 100 mg daily on day 21 and subsequently tapered as follows: 100 mg daily for one week, 80 mg daily for one week, and 60 mg daily for two weeks.

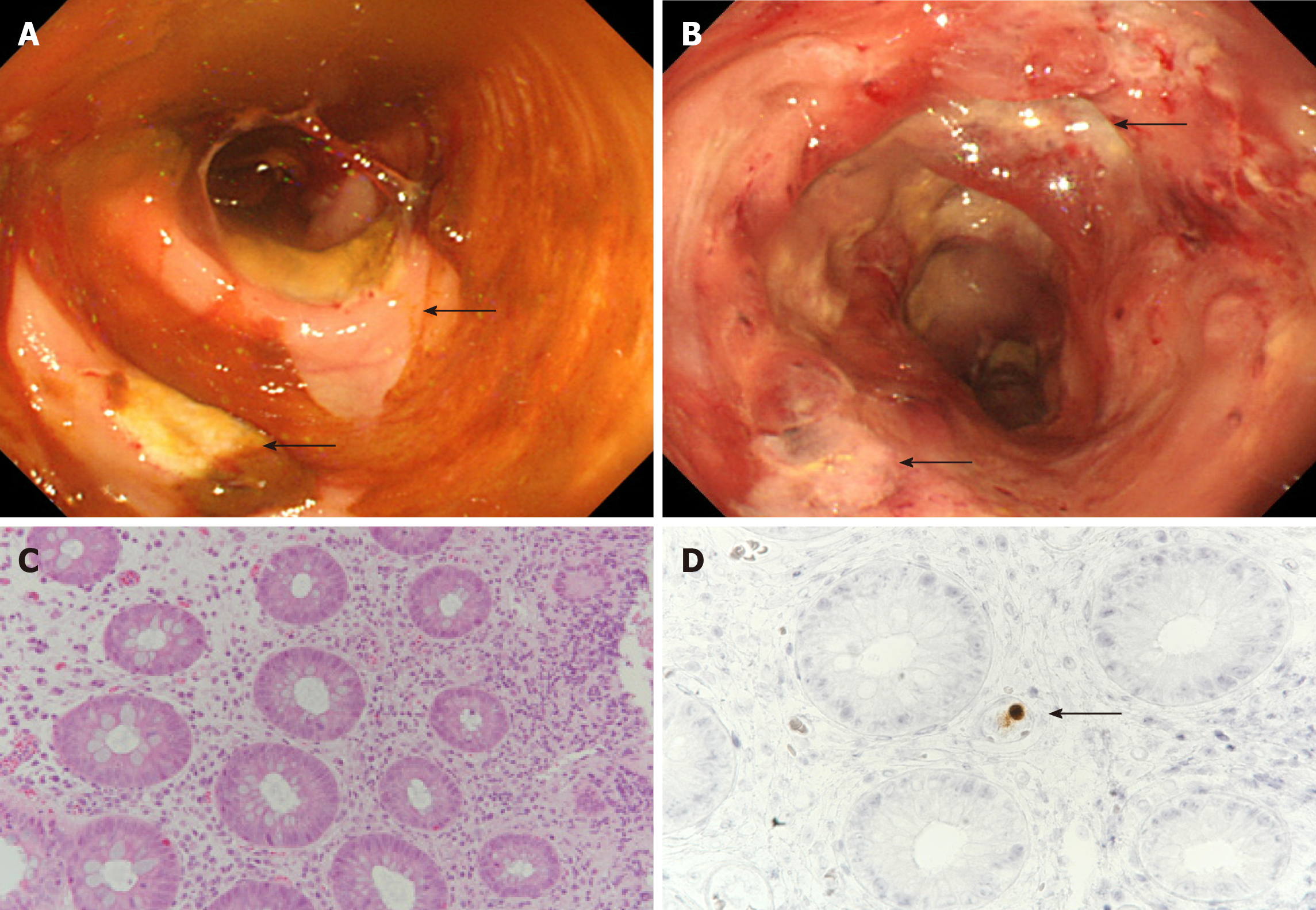

His bloody diarrhea, which had started on day 8, progressively worsened and we decided to perform a colonoscopy on day 22. The examination revealed multiple large ulcers in the sigmoid colon and rectum (Figure 2A and B). We biopsied one of the ulcers in the sigmoid colon, and the histopathological examination showed infiltration of neutrophils and lymphocytes as well as CMV-positive cells in the mucosa (Figure 2C and D). Based on these biopsy results and a CMV pp65 antigenemia (C7-HRP) test of the peripheral blood, which was positive in 20/50000 cells, we diagnosed the patient with CMV enterocolitis. We started treatment with ganciclovir (700 mg/d) on day 25.

Despite improved peripheral blood C7-HRP test results, the patient continued to have bloody diarrhea. On day 45, he complained of increasing abdominal pain. An abdominal computed tomography revealed free air, leading to the diagnosis of gastrointestinal perforation. Because of his poor general condition, surgical treatment was not considered. Unfortunately, the patient died the next day.

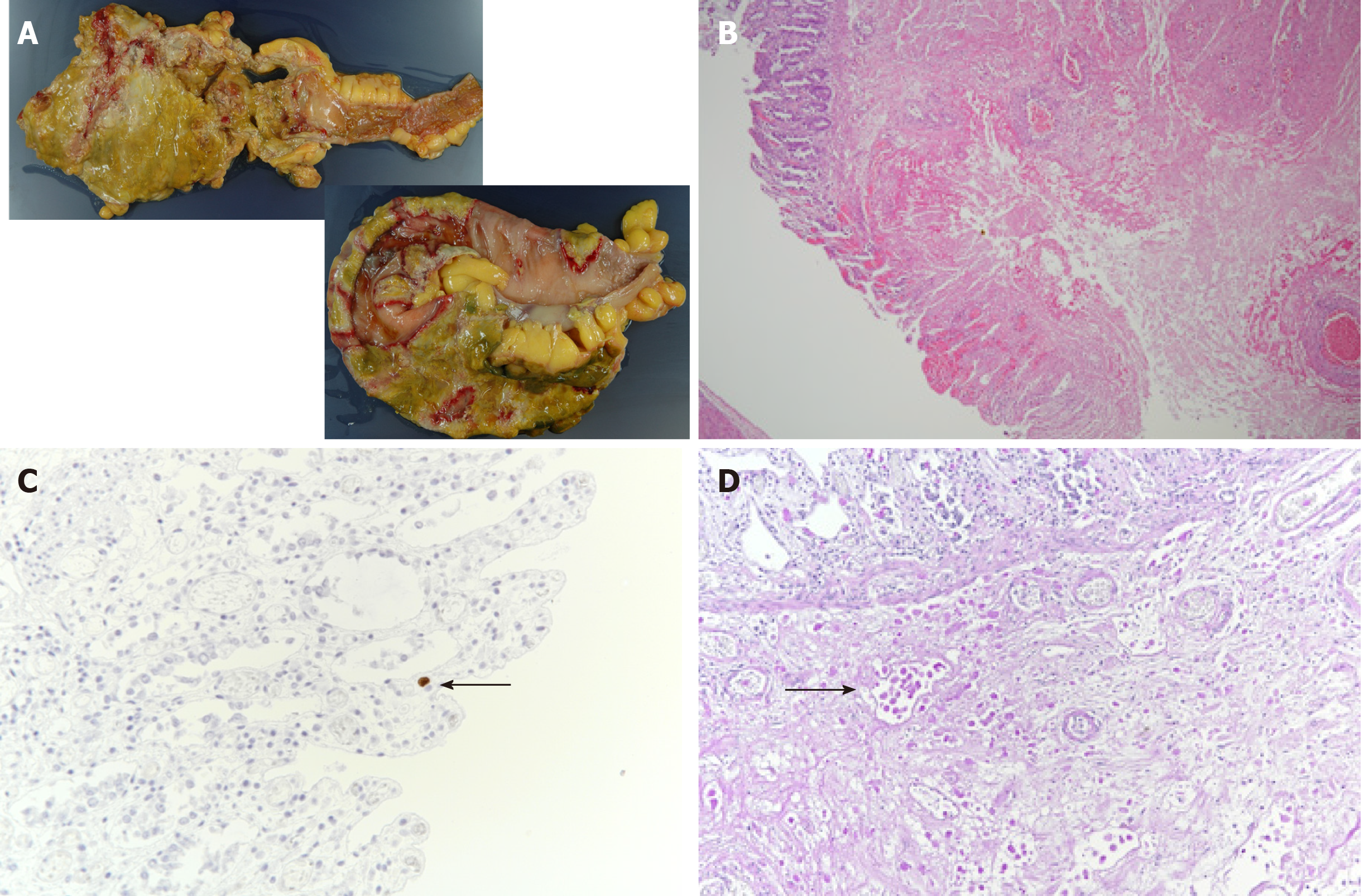

We performed an autopsy on the same day, where the pathologist noted full-thickness necrotic intestinal wall tissue throughout the entire colon (Figure 3A). We also detected severe infiltration of the necrotic tissue with ameba and a few CMV-positive cells in the colon (Figure 3B and C). We performed periodic acid–Schiff staining and detected Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites in the submucosa of the colon wall (Figure 3D).

We describe a patient with fulminant amebic colitis that progressed under steroid therapy. Initially, we had diagnosed the patient with CMV enterocolitis based on histopathological examination of a biopsy from one of several colon ulcers. However, despite starting ganciclovir and observing subsequent improvement of the peripheral blood antigenemia, the patient’s colitis symptoms worsened. Eventually, we could only make a posthumous diagnosis of fulminant amebic colitis and CMV enterocolitis based on the autopsy findings.

We did not consider amebic colitis in our differential diagnosis when the bloody diarrhea developed and, therefore, did not screen the stool sample for Entamoeba histolytica. Amebic colitis is an infection caused by Entamoeba histolytica and is a common cause of diarrhea worldwide, being more prevalent in developing countries. In developed countries, amebic colitis is generally seen in migrants from endemic areas[4]. The majority of Entamoeba histolytica infections are asymptomatic, with 4%-10% of previously asymptomatic patients developing symptoms each year and 10% of infections causing amebic colitis[5-7].

Fulminant amebic colitis is associated with a high mortality rate in patients with immunosuppressive comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus and chronic alcoholism[8]. Fulminant amoebic colitis has been reported in association with systemic steroid administration. Approximately 40% of patients with amebic colitis are initially misdiagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease and treated with steroids. There are reports of patients with asymptomatic amebic colitis who developed fulminant colitis after steroid administration[9]. As our patient was already immunosuppressed because of his diabetes mellitus, it is possible that he had subclinical amebic colitis, which only became apparent and progressed to the fulminant form after further immunosuppression by the steroid pulse therapy. Amebic colitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when signs of colitis are exacerbated by steroid treatment.

Complications of amebic colitis and CMV enterocolitis are more frequently reported in HIV-infected patients than in non-HIV-infected patients[10]. We had performed a biopsy of one of the colon ulcers and initially diagnosed the patient with CMV enterocolitis. Although we initiated treatment with ganciclovir and could see an improvement in the C7-HRP test results, the patient’s colitis symptoms did not improve. The specificity of positive CMV antigenemia for diagnosing CMV colitis is high, and the progressive reduction of antigen titers is associated with therapeutic effects[11,12]. In our case, we should have considered amebic colitis because of the discrepancy between the successful lowering of the CMV antigen titers and the unabated colitis symptoms.

Amebic colitis perforation is typically associated with high a mortality rate of 50% despite aggressive surgical treatment. Early treatment with anti-amebic agents as well as earlier and more targeted surgery is needed to improve survival of these patients[13]. Consequently, we advocate for early, preemptive anti-amebic treatment in the case of severe colitis that is resistant to other therapies, even before the underlying cause has been identified. Next-generation sequencing is an unbiased and rapid diagnostic tool that can be helpful for accurate diagnosis and treatment. A study reported surgical cases of acute appendicitis in HIV-infected patients; the E. histolytica polymerase chain reaction test result was positive in 15.8% (9/57) of the appendiceal specimens. Of the resected specimens, only two tested positive for amoebic colitis; however, a higher diagnostic rate can be expected using a next-generation sequencer[14].

We urge clinicians to consider Entamoeba histolytica infection if severe colitis progresses after steroid therapy. We recommend preemptive treatment of patients with colitis, even without a definite diagnosis, because of its poor prognosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cho YS, Meyer A, Zhang ZX S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Stanley SL Jr. Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 915] [Cited by in RCA: 813] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | National Institute of Infectious Diseases. Amebiasis in Japan, week 1 of 2007-week 43 of 2016. IASR. 2016;37:239-240. |

| 3. | Adams EB, MacLeod IN. Invasive amebiasis. I. Amebic dysentery and its complications. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56:315-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Summary of notifiable diseases, United States, 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;42:i-xvii; 1. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA Jr. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1565-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 563] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Gathiram V, Jackson TF. A longitudinal study of asymptomatic carriers of pathogenic zymodemes of Entamoeba histolytica. S Afr Med J. 1987;72:669-672. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Haque R, Ali IM, Sack RB, Farr BM, Ramakrishnan G, Petri WA Jr. Amebiasis and mucosal IgA antibody against the Entamoeba histolytica adherence lectin in Bangladeshi children. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1787-1793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takahashi T, Gamboa-Dominguez A, Gomez-Mendez TJ, Remes JM, Rembis V, Martinez-Gonzalez D, Gutierrez-Saldivar J, Morales JC, Granados J, Sierra-Madero J. Fulminant amebic colitis: analysis of 55 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1362-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shirley DA, Moonah S. Fulminant Amebic Colitis after Corticosteroid Therapy: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tsai HC, Lee SS, Wann SR, Chen YS, Chen ER, Yen CM, Liu YC. Colon perforation with peritonitis in an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patient due to cytomegalovirus and amoebic colitis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:839-842. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Chun J, Lee C, Kwon JE, Hwang SW, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC, Im JP. Usefulness of the cytomegalovirus antigenemia assay in patients with ulcerative colitis. Intest Res. 2015;13:50-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lino K, Trizzotti N, Carvalho FR, Cosendey RI, Souza CF, Klumb EM, Silva AA, Almeida JR. Pp65 antigenemia and cytomegalovirus diagnosis in patients with lupus nephritis: report of a series. J Bras Nefrol. 2018;40:44-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ozdogan M, Baykal A, Aran O. Amebic perforation of the colon: rare and frequently fatal complication. World J Surg. 2004;28:926-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kobayashi T, Watanabe K, Yano H, Murata Y, Igari T, Nakada-Tsukui K, Yagita K, Nozaki T, Kaku M, Tsukada K, Gatanaga H, Kikuchi Y, Oka S. Underestimated Amoebic Appendicitis among HIV-1-Infected Individuals in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:313-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |