Published online May 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3644

Peer-review started: January 17, 2021

First decision: February 11, 2021

Revised: March 16, 2021

Accepted: April 6, 2021

Article in press: April 6, 2021

Published online: May 26, 2021

Processing time: 113 Days and 21.8 Hours

Since the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the exclusion of a patient from COVID-19 should be performed before surgery. However, patients with type A acute aortic dissection (AAD) during pregnancy can seriously endanger the health of either the mother or fetus that requires emergency surgical treatment without the test for COVID-19.

A 38-year-old woman without Marfan syndrome was admitted to the hospital because of chest pain in the 34th week of gestation. She has diagnosed as having a Stanford type-A AAD involving an aortic arch and descending aorta via aortic computed tomographic angiography. The patient was transferred to the isolated negative pressure operating room in one hour and underwent cesarean delivery and ascending aorta replacement. All medical staff adopted third-level medical protection measures throughout the patient transfer and surgical procedure. After surgery, the patient was transferred to the isolated negative pressure intensive care unit ward. The nucleic acid test and anti-COVID-19 immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM were performed and were negative. The patient and infant were discharged without complication nine days later and recovered uneventfully.

The results indicated that the procedure that we used is feasible in patients with a combined cesarean delivery and surgery for Stanford type-A AAD during the COVID-19 outbreak, which was mainly attributed to rapid multidisciplinary consultation, collaboration, and quick decision-making.

Core Tip: The findings indicated that the procedure described is viable in patients with combined cesarean delivery and Stanford type-A acute aortic dissection surgery during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. In this case, a reasonable operation plan, practical procedures, and close cooperation among all departments were the keys to successful management.

- Citation: Liu LW, Luo L, Li L, Li Y, Jin M, Zhu JM. Combined cesarean delivery and repair of acute aortic dissection at 34 weeks of pregnancy during COVID-19 outbreak: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(15): 3644-3648

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i15/3644.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3644

More than 25% of patients with Stanford type A acute aortic dissection (AAD) are initially misdiagnosed, and the mortality rate approaches 50% in patients who do not receive appropriate treatment within 48 h[1]. Although AAD rarely presents in women younger than 40 years of age, the risk increases when they become pregnant[2]. Reports have also indicated that timely, well-defined surgical management during pregnancy does not differ significantly from standard procedures and has a favorable outcome for both the mother and infant[3]. Since the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the exclusion of a patient from COVID-19 should be performed before surgery. However, patients with type A AAD during pregnancy can seriously endanger the health of either the mother or fetus that requires emergency surgical treatment without the test for COVID-19. We describe here a case of type A AAD during advanced pregnancy during the COVID-19 outbreak.

A 38-year-old woman (gravida 3, para 2) at 34 wk of gestation had an acute onset of chest and upper abdominal pain with transient syncope and intermittent bloody stools and was referred to a local community hospital. The pain continued for 24 h, and since the patient’s condition could not be relieved, she was transferred to the Emergency Department of Anzhen Hospital.

The patient had no history of present illness.

The patient had no history of hypertension, coronary disease, diabetes mellitus, or previous trauma surgery.

The patient had no family history of AAD.

On the day of admission (May 13, 2020), the patient had a blood pressure of 140/70 mmHg, heart rate of 90 bpm, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, oxygen saturation of 98% indoors, and temperature of 36.5 °C. Clinical examination was normal. On arrival, the patient had no history of contact with COVID-19 cases. Since the surgical repair would be operated immediately, the exclusion of a patient from COVID-19 was not performed, including nucleic acid tests and computed tomography (CT) scan of the lungs. Moreover, the fetal heart rate was standard and was monitored continuously through heart rate monitoring or fetal ultrasound.

No abnormality was found.

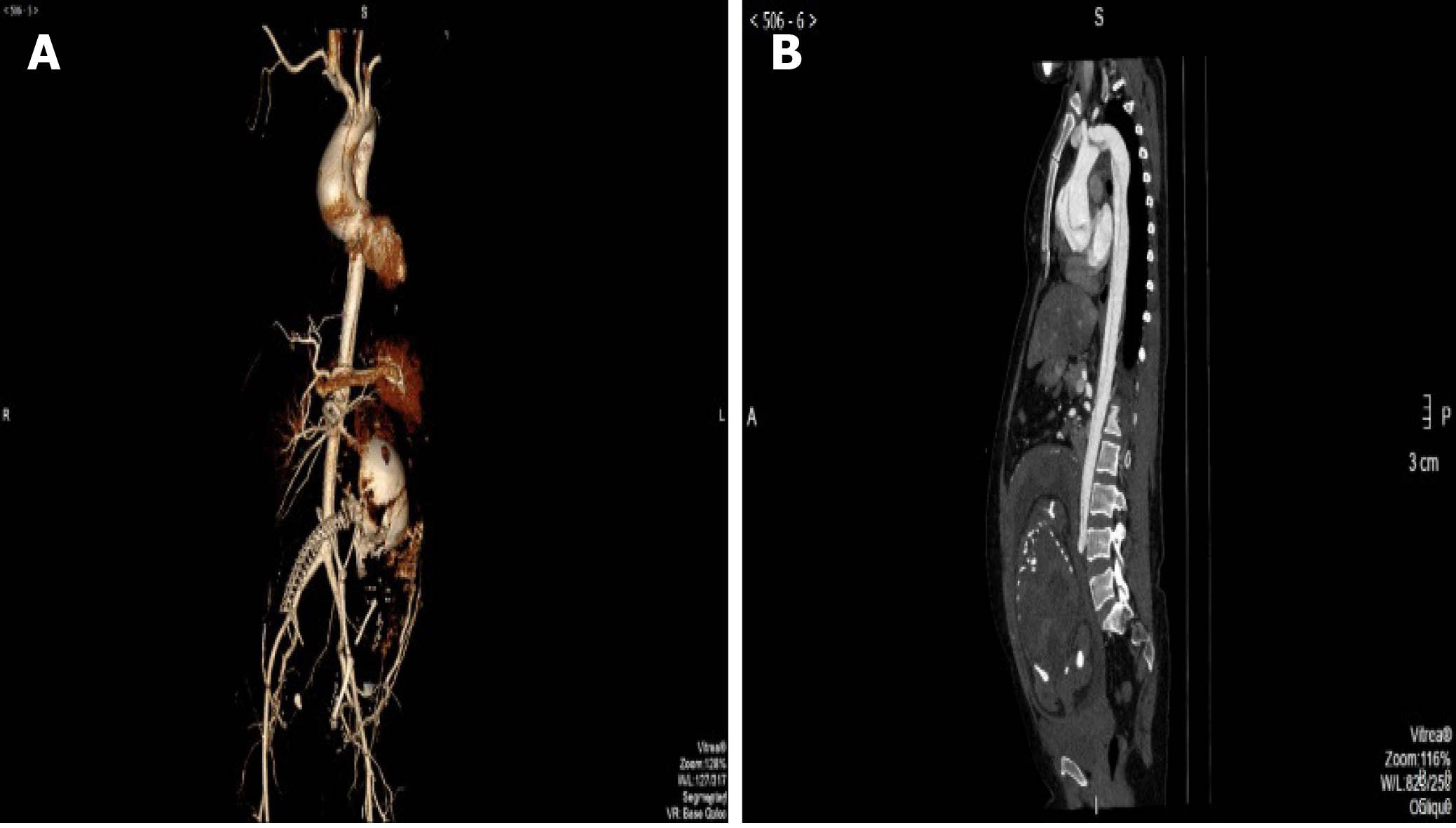

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed an AAD, and then a type-A AAD was diagnosed through CT (Figure 1). The intimal tear originated at the proximal thoracic aorta level, and the dissection extended into the aortic arch and the iliac artery except for the coronary arteries. The aorta valve was a bicuspid aortic valve, and there was minimal aortic insufficiency. The aortic root and ascending aorta presented with dilatation of up to 46 mm, but the descending aorta had regular dimensions. Furthermore, the right renal artery was located in the true lumen.

The patient was confirmed to have type A AAD in the 34th gestational week, and the fetus was stable without intrauterine distress. A simultaneous operation was decided to perform, with a combined cesarean delivery of the infant and surgical management of the patient’s aortic dissection. All medical staff adopted third-level medical protection measures throughout the patient transfer and surgical procedure (Figure 2), including medical-degree mask (N95), disposable surgical cap, properly wearing disposable protective clothing, disposable shoe covers, and disposable latex gloves, and medical-degree goggles[4,5]. The multidisciplinary team consisted of cardiothoracic surgeons, anesthesiologists, obstetricians, neonatologists, cardiac perfusionists, and experienced nurses[6].

When the patient arrived in the operating room, sodium nitroprusside was used to maintain her blood pressure below 150/90 mmHg. A rapid-sequence induction of general anesthesia was conducted while the patient was in the left uterine displacement position, and then endotracheal intubation was performed successfully. At the same time of intubation, cesarean delivery was performed by the obstetrician. One and half hours after arriving at the emergency department, a cesarean section was operated, and a live-born 2670-g female infant was delivered 5 min later. The 1-, 5-, and 10-min Apgar scores were 10, 10, and 10, respectively. Uterine compression sutures with intrauterine balloon tamponade were performed. The estimated total blood loss was 150 mL. During this period, blood pressure was controlled at 110-150/60-90 mmHg. After adequate hemostasis by obstetricians, the patient was heparinized fully and operated on for aortic dissection. After cardiopulmonary bypass was initiated, the aortotomy revealed the intimal breakage being located in the ascending aorta. Then, an ascending aorta replacement was performed (Figure 3). The procedure was uneventful with cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross-clamp of 133 min and 59 min. No blood products were transfused during the operation. After surgery, the patient was transferred to the isolated negative pressure intensive care unit ward. The nucleic acid test and anti-COVID-19 immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM were performed and were negative.

The patient was discharged without complications nine days later.

In our case, the decision to perform the cesarean section before aortic surgery would provide the mother with the best chance of survival and a less negative influence on the fetus. In the operating room, we tried to strike a delicate balance between minimizing the risk of aortic rupture and maintaining the fetus's needs using a general anesthetic and vasoactive drugs, such as nicardipine and phenylephrine. Despite all this, the fetus had to be delivered as quickly as possible. After delivery of the fetus, uterine contractions and oxytocin injection would result in a sudden increase in the circulating blood volume and elevation of the acute blood pressure leading to aortic rupture. Because the main reason for postpartum hemorrhage is uterine atony, intrauterine balloon tamponade was performed to prevent severe bleeding. Acceptable blood loss occurred during the cesarean delivery, which proved the correctness of our decision.

Despite the strong infectivity of COVID-19, many patients are confused about a timely diagnosis[7]. According to the patient who would not be excluded from COVID-19, our third-level medical protection measures were feasible and effective to avoid cross-infection in the hospital.

The findings indicated that the procedure described is viable in patients with combined cesarean delivery and Stanford type-A AAD surgery during the COVID-19 outbreak. In this case, a reasonable operation plan, practical procedures, and close cooperation among all departments were the keys to successful management.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sintusek P S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Evangelista A, Isselbacher EM, Bossone E, Gleason TG, Eusanio MD, Sechtem U, Ehrlich MP, Trimarchi S, Braverman AC, Myrmel T, Harris KM, Hutchinson S, O'Gara P, Suzuki T, Nienaber CA, Eagle KA; IRAD Investigators. Insights From the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection: A 20-Year Experience of Collaborative Clinical Research. Circulation. 2018;137:1846-1860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 860] [Article Influence: 143.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kamel H, Roman MJ, Pitcher A, Devereux RB. Pregnancy and the Risk of Aortic Dissection or Rupture: A Cohort-Crossover Analysis. Circulation. 2016;134:527-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ch'ng SL, Cochrane AD, Goldstein J, Smith JA. Stanford type a aortic dissection in pregnancy: a diagnostic and management challenge. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang CH, Ma WG, Zhong YL, Ge YP, Li CN, Qiao ZY, Liu YM, Zhu JM, Sun LZ. Management of acute type A aortic dissection during COVID-19 outbreak: Experience from Anzhen. J Card Surg. 2020 epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | He H, Zhao S, Han L, Wang Q, Xia H, Huang X, Yao S, Huang J, Chen X. Anesthetic Management of Patients Undergoing Aortic Dissection Repair With Suspected Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome COVID-19 Infection. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:1402-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Patel PA, Fernando RJ, MacKay EJ, Yoon J, Gutsche JT, Patel S, Shah R, Dashiell J, Weiss SJ, Goeddel L, Evans AS, Feinman JW, Augoustides JG. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection in Pregnancy-Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges in a Multidisciplinary Setting. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32:1991-1997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fukuhara S, Rosati CM, El-Dalati S. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:e405-e407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |