Published online May 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3637

Peer-review started: October 7, 2020

First decision: November 14, 2020

Revised: December 28, 2020

Accepted: March 19, 2021

Article in press: March 19, 2021

Published online: May 26, 2021

Processing time: 209 Days and 20.1 Hours

A high degree of vigilance is warranted for a spinal infection, particularly in a patient who has undergone an invasive procedure such as a spinal injection. The average delay in diagnosing a spinal infection is 2-4 mo. In our patient, the diagnosis of a spinal infection was delayed by 1.5 mo.

A 60-year-old male patient with a 1-year history of right-sided lumbar radicular pain failed conservative treatment. Six weeks to prior to surgery he received a spinal injection, which was followed by increasing lumbar radicular pain, weight loss and chills. This went unnoticed and surgery took place with right-sided L4-L5 combined microdiscectomy and foraminotomy via a posterior approach. The day after surgery, the patient developed left-sided lumbar radicular pain. Blood cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). Magnetic resonance imaging showed inflammatory aberrations, revealing septic arthritis of the left-sided L4/L5 facet joint as the probable cause. Revision surgery took place and S. aureus was isolated from bacteriological samples. The patient received postoperative antibiotic treatment, which completely eradicated the infection.

The development of postoperative lower back pain and/or lumbar radicular pain can be a sign of a spinal infection. A thorough clinical and laboratory work-up is essential in the preoperative evaluation of patients with spinal pain.

Core Tip: This is the case report of a 60-year-old male patient with right-sided L4-L5 Lumbar disc herniation who underwent right-sided transforaminal injection with no improvement and a decision was made to carry out surgery. On day 1 postoperatively he developed excruciating left-sided lumbar radicular pain. Investigations and retrospective analyses demonstrated left-sided septic L4-L5 facet joint arthritis caused by Staphylococcus aureus, most probably as a result of the spinal injections 6 wk prior to surgery. The infection was successfully treated with revision surgery and antibiotic therapy.

- Citation: Kerckhove MFV, Fiere V, Vieira TD, Bahroun S, Szadkowski M, d'Astorg H. Postoperative pain due to an occult spinal infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(15): 3637-3643

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i15/3637.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3637

Lumbar disc herniation (LDH) is a common cause of lower back pain and lumbar radicular pain. Conservative treatment consisting of analgesic drugs, anti-inflammatory drugs and adapted movement is generally favourable in the general population, with complete recovery in 70%-80% of cases[1]. Spinal injections are commonly used as an additional treatment. One of the potential risks of spinal injection is infection. A review by Windsor et al[2] reported the occurrence of infections after 1%-2% and severe infections after 0.01%-0.1% of all spinal injections. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is the most common organism isolated and is thought to be introduced through the skin by needle puncture[3].

We report the case of a patient with right-sided L4-L5 LDH. During conservative treatment he underwent right-sided transforaminal injection. This did not lead to an improvement in his symptoms and a decision was made to carry out surgery. In the immediate postoperative period, he progressed favourably with temporary relief of pain, but on day 1 postoperatively he developed excruciating left-sided lumbar radicular pain. Investigations and retrospective analyses demonstrated left-sided septic L4-L5 facet joint arthritis caused by S. aureus, most probably as a result of the spinal injections 6 wk prior to surgery. The infection was successfully treated with revision surgery and antibiotic therapy.

The patient was informed that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication and gave his consent. The study received institutional review board approval (COS-RGDS-2020-04-002-DASTORG-H).

A 60-year-old male patient was admitted to hospital for treatment of right-sided lumbar radicular pain.

Clinically, there was irradiating right leg pain in the L4 dermatome. The patient had a 1-year history of this symptom.

He did not have a past history of low back pain or LDH.

The patient had no clinically relevant comorbidities, except for being overweight (body mass index of 27). The patient had no prior relevant medical history. He was a non-smoker, had no allergies and was not diabetic. The patient didn’t have any family history related to low back pain or LDH.

Physical examination demonstrated a motor deficit of his right quadriceps, with 4/5 strength.

Preoperative laboratory tests showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 11 000/µl, normal creatinine and normal haemostatic parameters. C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were not measured preoperatively as this is not done routinely in our department for non-instrumented spinal surgery.

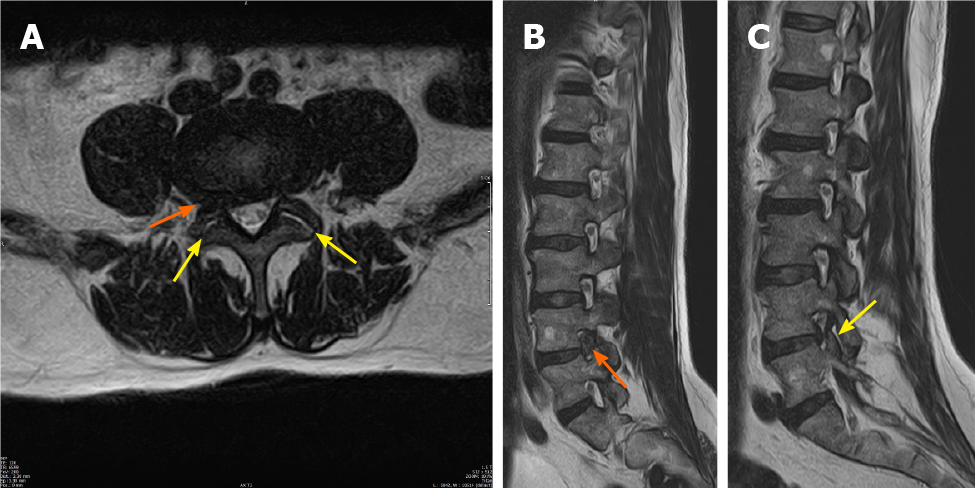

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed 2 d before the last infiltration, 1.5 mo prior to surgery, showed right-sided L4-L5 foraminal LDH, with compression of the right L4 nerve root. Intra-articular fluid collection was seen in the facet joints of L4-L5, without the presence of other inflammatory findings in the L4-L5 area (Figure 1).

He underwent extensive but unsuccessful conservative treatment with oral analgesics (paracetamol 1 g (1-1-1-1) and ibuprofen 600 mg (1-1-1)), rest and two right-sided L4-L5 transforaminal injections over a period of 1 year, with no clinical improvement. Over the last 3 mo, his level of pain had increased significantly, with a combination of irradiating right-sided leg pain and lower back pain.

Six weeks prior to surgery, our patient received a second right-sided transforaminal injection with cortisone. In the period following this injection, his pain level increased further, with a combination of irradiating right-sided leg pain and lower back pain. His treating physician subsequently increased his oral pain medication to level 3 analgesia with oxycodon 10 mg (1-1-1), but this failed to provide pain relief. In addition, cortisone-therapy with intramuscular solumedrol was instituted without success. This led to the consultation for surgery.

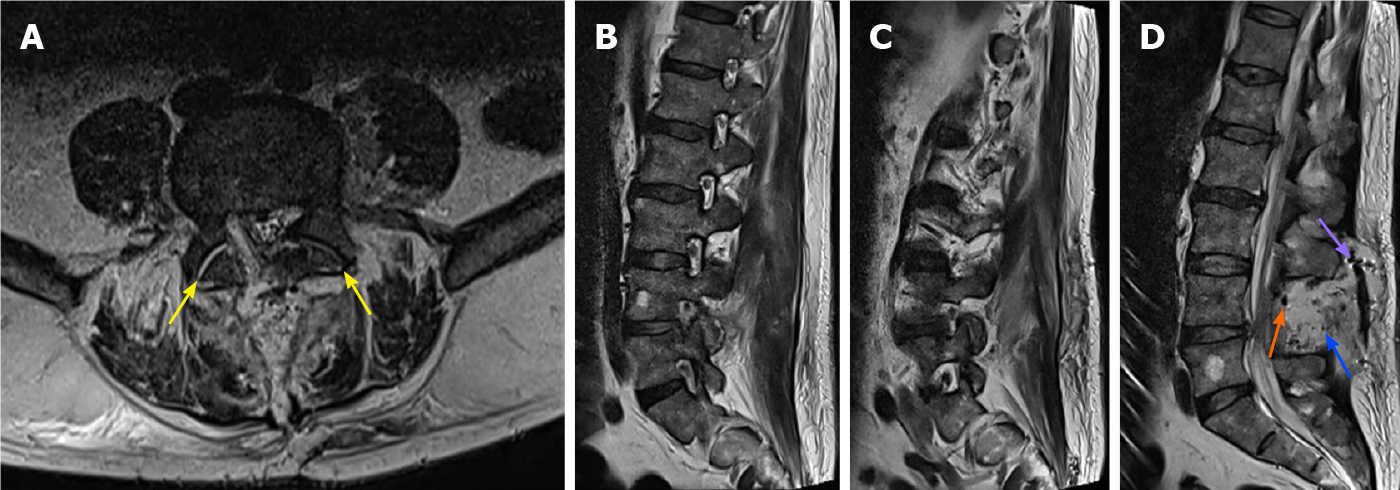

Bilateral microdecompression and right-sided L4-L5 combined microdiscectomy and foraminotomy by the posterior approach were carried out successfully. Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis consisted of 2 g intravenous (IV) cefazolin. There were no clear intra-operative findings suggestive of infection. In the immediate postoperative period, the patient had complete relief from right-sided irradiating leg pain and was very satisfied. On the first day after the operation, he developed an excruciating irradiating pain in his left leg, which was contralateral to the side of the original herniation. The pain persisted and an MRI scan was carried out on day 4 postoperatively. This was almost normal, with bilateral decompression of L4-L5 and a small fluid collection in the left-sided facet joint of L4-L5 (Figure 2). No recurrent LDH, haematoma, or middle- to high-grade compressive pathology that could explain the new pattern of irradiating pain in the left leg was noted.

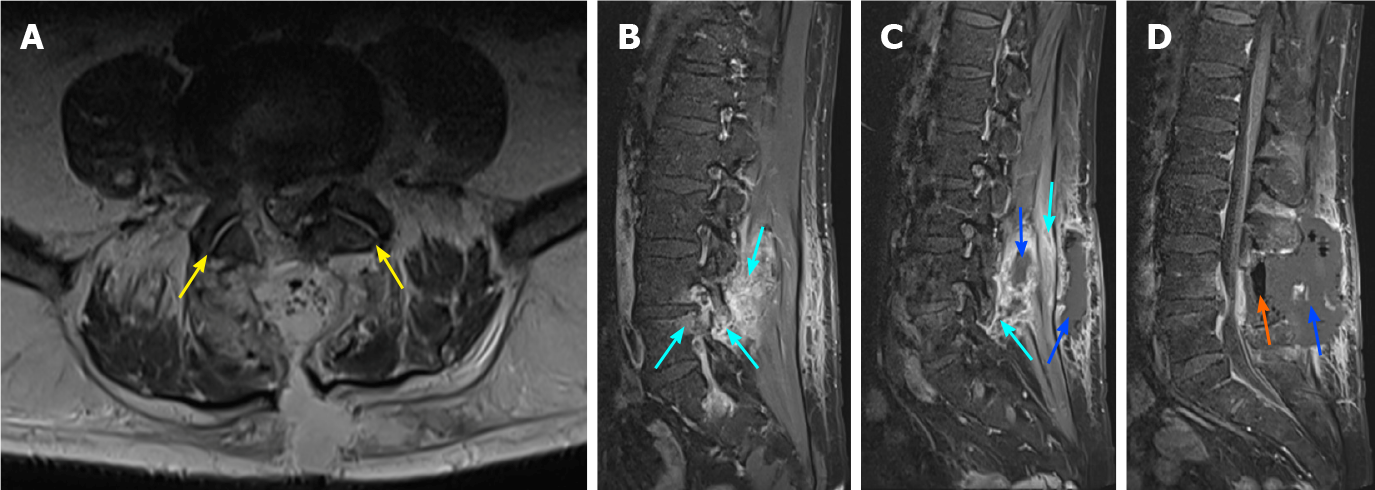

The patient remained in hospital for further observation. On day 5 post-surgery he developed a fever of 39 °C and chills. The clinical appearance of his wound was normal. As a standard measure in our hospital, with fever > 38.5 °C, blood cultures were taken and these grew S. aureus. With the high-level of suspicion of an infection, a second MRI scan was carried out on day 6 postoperatively, showing an increase in fluid collection in the posterior spine and the presence of air collections and inflammatory changes around the left-sided facet joint of L4-L5 (Figure 3).

Septic arthritis of the left-sided L4/L5 facet joint, with S. aureus.

Revision surgery was performed 6 d after the first operation, with evacuation of the fluid collection. Bacteriological samples were taken, drainage, debridement and lavage were performed. Antibiotic therapy was instituted, initially empirically with IV vancomycin 1 g (1-0-1) and IV cloxacillin 3 g (1-1-1-1) for 5 d. In view of the antibiogram (Table 1), his antibiotic therapy was switched to IV cefazolin (2 g; 1-1-1) for 23 d, at home, through a central catheter inserted peripherally. After this time, his antibiotic therapy was switched to oral ofloxacin (400 mg; 1-0-0) and rifampicin (600 mg; 1-0-0) for 2 wk.

| Antibiotic | |

| Penicillin G | Resistant |

| Oxacillin | Sensitive |

| Gentamicin | Sensitive |

| Kanamycin | Sensitive |

| Tobramycin | Sensitive |

| Ofloxacin | Sensitive |

| Erythromycin | Sensitive |

| Lincomycin | Sensitive |

| Pristinamycin | Sensitive |

| Linezolid | Sensitive |

| Teicoplanin | Sensitive |

| Vancomycin | Sensitive |

| Tetracycline | Sensitive |

| Fosfomycin | Sensitive |

| Nitrofurantoin | Sensitive |

| Fusidic acid | Sensitive |

| Rifampicin | Sensitive |

| Trimetoprim sulfametoxazol | Sensitive |

His inflammatory parameters returned to normal over a period of 3 wk. Three months after surgery, he was not taking any pain medication and had no leg pain, although there was a persisting motor deficit of the right quadriceps, with 4/5 strength, and he was easily fatigued. Through a rehabilitation program his physical condition improved significantly, so that at his 9-mo follow-up appointment he was already playing sport again, with a lot of walking and swimming.

A detailed medical history was taken after his revision surgery and he stated that, during the 6 wk prior to surgery, he had lost 12 kg in weight, which he had attributed to the pain, and chills, which he had attributed to the use of opioids and which he had not reported to the medical staff. These cardinal symptoms of an infection, weight loss and chills, started 4 d after the last right-sided transforaminal L4-L5 injection.

In our patient, the diagnosis of a spinal infection was delayed by 6 wk. It should be noted that the average delay in diagnosing a spinal infection is 2-4 mo[4]. This shows that a high level of vigilance for a spinal infection is warranted, especially in patients who are more susceptible to developing an infection, such as those who are immunocompromised, diabetic, dialysis-dependent, have permanent vascular access, or are IV drug abusers[5]. A high degree of vigilance is also necessary in patients undergoing invasive procedures such as spinal injections[2]. In this case, we presume that the first surgery resulted in a stress response, as proposed by Bardram et al[6], which might have decreased the immune response to the infection and, as such, might have led to an increase in the extent of the infection.

Monitoring for a possible spinal infection can be achieved by focusing on history taking, clinical examination and laboratory results. Typical signs of an infection are fever, night sweats, chills, night pain, pain resistant to analgesics and weight loss. In this case, these symptoms were not mentioned by the patient and were not discovered by the clinicians prior to surgery. Routine questioning about these symptoms could improve the sensitivity of detection of an underlying infection.

A literature review by Yoon et al[7] showed that approximately 50% of cases of septic arthritis of the facet joint have leukocytosis and all previous case reports (n = 61) except for one, had an elevated ESR and/or CRP. In our patient, ESR and CRP were not measured in the preoperative work-up as this is not done routinely in our hospital for non-instrumented spinal surgery. Our patient’s WBC count was at the upper limit of normal at 11000/μL. Routine measurement of ESR and CRP levels could improve the sensitivity of detection of an underlying infection. Moreover, patients with fever and back pain following an invasive procedure should have blood cultures performed routinely, as these are positive in around 60% of cases of bacterial spondylodiscitis[8]. In our hospital, sequential blood cultures are performed as a standard procedure in patients with fever > 38.5 °C, and in the present case, they were positive for S. aureus. In the first few day’s post-surgery, body temperature rises frequently as a result of the inflammatory reaction to surgical trauma, but in most of these cases blood cultures remain negative. In our patient, a positive blood culture was a milestone since his MRI scan showed no conclusive results.

There is no gold-standard treatment for septic arthritis of the facet joint and treatment is based on a retrospective evaluation of case series[9]. The majority of cases are treated conservatively with IV and oral antibiotics. The literature provides no clear guidance regarding the duration and route of administration of antibiotic therapy[10]. Generally, antibiotics are given for a period of 6-8 wk[11-14]. Sometimes this treatment has to be accompanied by bed rest and an orthosis for pain management[15]. Surgery is not usually indicated and is reserved for patients with an infection that is refractory to antibiotics, or with the presence of neurological deficits[12,16]. In the present case, due to the pattern of excruciating left-sided lumbar radicular pain, surgery was performed and led to a quick and significant improvement in his pain levels. He was then treated with IV and oral antibiotics for a period of approximately 6 wk. We do not have a clear explanation as to why the signs and symptoms of infection developed on the contralateral side to the surgery. We presume that this could be due to direct spread from the infiltration to the contralateral side, or due to an infiltration of the wrong-side.

The limitations of a case report design are well recognized, especially regarding external validity. However, given the rarity of this condition, the level of evidence for the optimal diagnosis of spine septic arthritis is not well-established, therefore we consider this case report important.

The development of post-operative lower back pain and/or lumbar radicular pain can be a signal of a spinal infection. A thorough clinical and laboratory work-up (CRP, ESR, leukocyte count) is essential for the preoperative evaluation of spinal patients, to identify any underlying infection.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: France

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Higa K S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Boos N, Aebi M. Spinal Disorders: Fundamentals of Diagnosis and Treatment. 1st ed. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2008. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Windsor RE, Storm S, Sugar R. Prevention and management of complications resulting from common spinal injections. Pain Physician. 2003;6:473-483. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Goodman BS, Posecion LW, Mallempati S, Bayazitoglu M. Complications and pitfalls of lumbar interlaminar and transforaminal epidural injections. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1:212-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gasbarrini AL, Bertoldi E, Mazzetti M, Fini L, Terzi S, Gonella F, Mirabile L, Barbanti Bròdano G, Furno A, Gasbarrini A, Boriani S. Clinical features, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to haematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2005;9:53-66. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Babic M, Simpfendorfer CS. Infections of the Spine. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31:279-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Jensen P, Crawford ME, Kehlet H. Recovery after laparoscopic colonic surgery with epidural analgesia, and early oral nutrition and mobilisation. Lancet. 1995;345:763-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoon J, Efendy J, Redmond MJ. Septic arthritis of the lumbar facet joint. Case and literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;71:299-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mylona E, Samarkos M, Kakalou E, Fanourgiakis P, Skoutelis A. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: a systematic review of clinical characteristics. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39:10-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | André V, Pot-Vaucel M, Cozic C, Visée E, Morrier M, Varin S, Cormier G. Septic arthritis of the facet joint. Med Mal Infect. 2015;45:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Duarte RM, Vaccaro AR. Spinal infection: state of the art and management algorithm. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:2787-2799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Halpin DS, Gibson RD. Septic arthritis of a lumbar facet joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:457-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Muffoletto AJ, Ketonen LM, Mader JT, Crow WN, Hadjipavlou AG. Hematogenous pyogenic facet joint infection. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:1570-1576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Klekot D, Zimny A, Czapiga B, Sąsiadek M. Isolated septic facet joint arthritis as a rare cause of acute and chronic low back pain - a case report and literature review. Pol J Radiol. 2012;77:72-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ergan M, Macro M, Benhamou CL, Vandermarcq P, Colin T, L'Hirondel JL, Marcelli C. Septic arthritis of lumbar facet joints. A review of six cases. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1997;64:386-395. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Narváez J, Nolla JM, Narváez JA, Martinez-Carnicero L, De Lama E, Gómez-Vaquero C, Murillo O, Valverde J, Ariza J. Spontaneous pyogenic facet joint infection. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:272-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rajeev A, Choudhry N, Shaikh M, Newby M. Lumbar facet joint septic arthritis presenting atypically as acute abdomen - A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;25:243-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |