Published online May 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3597

Peer-review started: January 11, 2021

First decision: February 23, 2021

Revised: February 26, 2021

Accepted: March 29, 2021

Article in press: March 29, 2021

Published online: May 26, 2021

Processing time: 119 Days and 18.5 Hours

Dyspepsia is one of the commonest clinical disorder. However, controversy remains over the role of endoscopy in patients with dyspepsia. No studies have evaluated the diagnostic value of endoscopy in patients with no warning symptoms according to the Rome IV criteria.

To study the diagnostic value of endoscopy in dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms.

This cross-sectional study included dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria at The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University from April 2018 to February 2019. The clinical data were collected using questionnaires, including dyspeptic information, warning symptoms, other diseases, family history and basic demographic data. Based on dyspeptic symptoms, patients can be divided into epigastric pain syndrome, postprandial distress syndrome or overlapping subtypes.

A total of 1016 cases were enrolled, 304 (29.9%) had clinically significant findings that were detectable by endoscopy. The endoscopy findings included esophageal lesions in 180 (17.7%) cases, peptic ulcers in 115 (11.3%) cases and malignancy in 9 (0.89%) patients. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that males [odds ratio (OR) = 1.758, P < 0.001], body mass index > 25 (OR = 1.660; P = 0.005), epigastric pain (OR = 1.423; P = 0.019) and Helicobacter pylori infection (OR = 1.949; P < 0.001) were independently associated with risk factors for the presence of clinically significant findings on endoscopy.

Chinese patients with dyspepsia with no warning symptoms should undergo endoscopy, particularly males, patients with body mass index > 25, epigastric pain or Helicobacter pylori infection.

Core Tip: We found that the incidence rate of malignancy (0.89%) among dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms was high. Moreover, the prevalence of significant endoscopic findings did not increase with age, but the incidence rate of malignancy (1.40%) was relatively higher in patients ≥ 50 years of age. Furthermore, the data suggested that male gender, body mass index > 25, epigastric pain and Helicobacter pylori infection were independently associated with significant endoscopic findings. Therefore, endoscopy should be the initial management strategy for dyspeptic Chinese patients even in the absence of warning features.

- Citation: Mao LQ, Wang SS, Zhou YL, Chen L, Yu LM, Li M, Lv B. Clinically significant endoscopic findings in patients of dyspepsia with no warning symptoms: A cross-sectional study. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(15): 3597-3606

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i15/3597.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3597

Dyspepsia is a common upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptom. The proportion of people that suffer from dyspepsia is between 7% to 45% of the whole population in different countries[1,2]. Based on the endoscopic findings, dyspepsia can be subdivided into organic dyspepsia and functional dyspepsia (FD). According to the Rome IV Committee definition, patients with FD should have at least one of the following symptoms: Postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain or epigastric burning. In addition, these symptoms must not be explained by any structural diseases and should persist for > 3 mo from the onset of symptom for ≥ 6 mo before diagnosis. Patients with FD can be divided into subtypes as epigastric pain syndrome (EPS), postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) or EPS-PDS overlap[3].

The causes of these various indigestion syndrome complexes are poorly understood. Currently, endoscopy remains an important step in the diagnosis and management of dyspepsia. It acts as an effective method to differentiate patients with clinically significant findings (CSFs), such as erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and gastroesophageal malignancy, from those with FD. If these lesions are identified in the early stages, the success rate of treatment and the quality of life will improve. However, endoscopy is an invasive procedure that is relatively expensive. Therefore, the selective use of endoscopy in high-risk patients would be the most cost-effective approach.

Although several proposed guidelines exist for the management of dyspepsia, the appropriate initial management strategy remains controversial. Some Western guidelines suggest that an empiric trial of acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors for 4-8 wk combined with noninvasive Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) testing and treatment before the endoscopic evaluation of patients without a clinically significant history, such as a family history of upper GI malignancy, unintended weight loss, signs of bleeding or iron deficiency anemia, progressive dysphagia, odynophagia, persistent vomiting, palpable mass, lymphadenopathy or jaundice. For these low-risk patients, endoscopy is recommended if symptoms persist following the initial noninvasive approach[4,5].

However, these guidelines are based on the study of dyspepsia in Western populations. Because of the high prevalence rates of H. pylori infection and upper GI malignancy in China[6-8], it is not known whether the same guidelines could be followed. In addition, the treating physicians fear missing clinically significant endoscopic findings in patients with no warning symptoms if endoscopy is not conducted, and it is unclear whether a substantial proportion of cases with symptoms would be missed.

This study aims to clarify the prevalence of significant endoscopic findings, particularly the proportion of cancer in Chinese patients with dyspepsia, and to further explore the clinical diagnostic value of endoscopy in dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms.

This cross-sectional study included patients that underwent endoscopy for dyspepsia at the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University from April 2018 to February 2019. The patients had at least one of the following symptoms: (1) Postprandial fullness; (2) Early satiation; (3) Epigastric pain; or (4) Epigastric burning. These symptoms should persisted for > 3 mo with the onset of symptom ≥ 6 mo previously. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Predominant symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, such as reflux and heartburn; (2) Presence of one or more warning features, which included a family history of upper GI malignancy, unintended weight loss, signs of bleeding or iron deficiency anemia, progressive dysphagia, persistent vomiting, palpable mass or lymphadenopathy or jaundice; (3) Previous history of GI surgery, malignancy, liver failure, gallbladder stones and cholecystitis; or (4) Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers before the study.

Before undergoing endoscopy, all the study participants were systematically evaluated using a questionnaire similar to that of the Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire (LDQ)[9]. We translated the Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire into Mandarin and added two indicators: Epigastric burning and postprandial fullness. This version also included demographics (sex and age), general health [weight and height to calculate body mass index (BMI)], other diseases and family history.

Based on the Rome IV Committee definition, we further divided the patients into three subgroups: EPS, PDS and EPS-PDS.

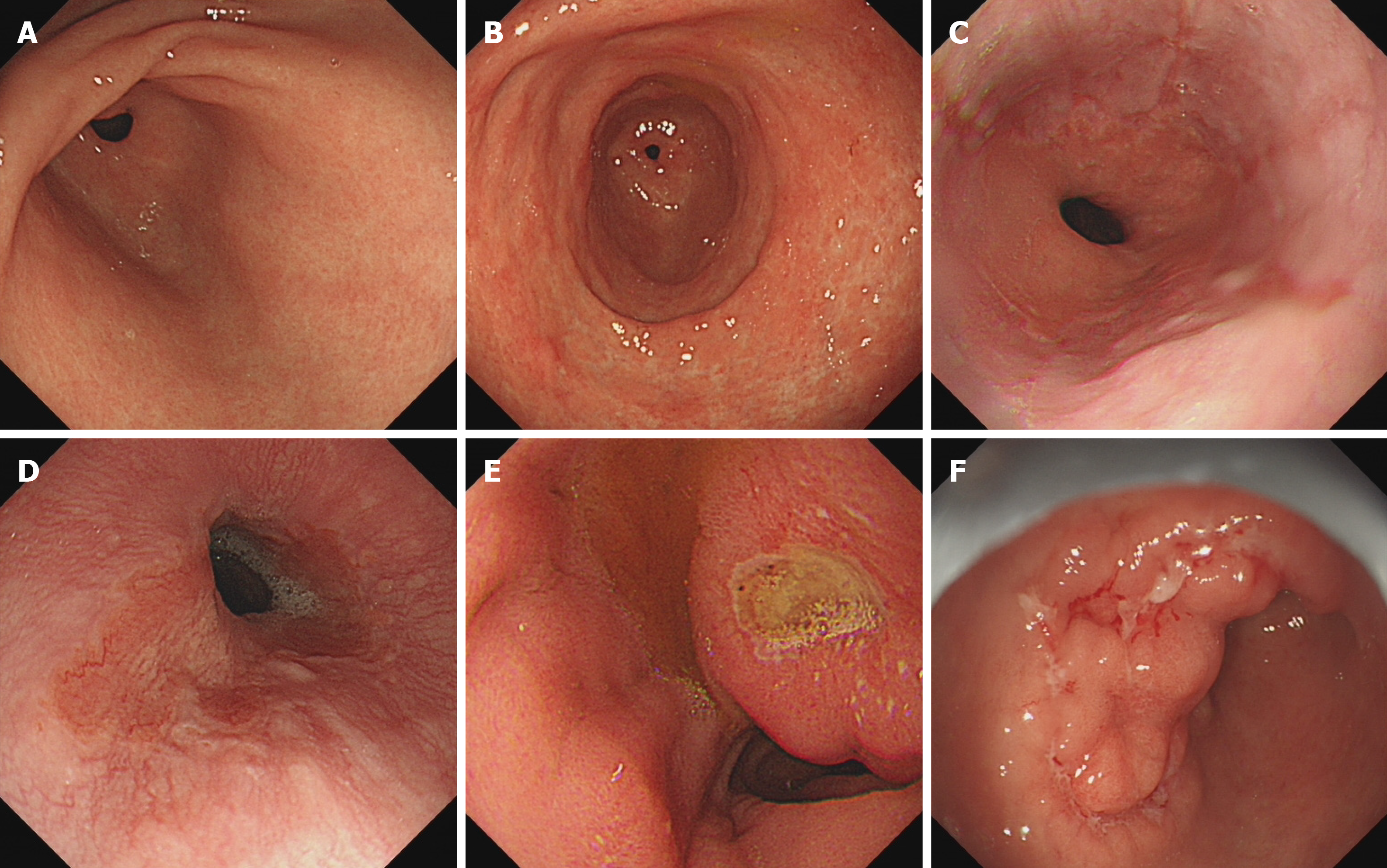

Endoscopy was carried out as an outpatient procedure with a standard endoscope (Olympus) by an experienced endoscopist. As shown in Figure 1, the endoscopic findings were classified as CSFs or general findings. The CSFs included reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, peptic ulcer, malignancy, etc. In addition, reflux esophagitis was graded according to the Los Angeles classification system[10]. The general findings included chronic atrophic gastritis or chronic superficial gastritis.

We took three biopsies from the antrum (the lesser curve), the corpus (the lesser curve) and the incisura angularis. An additional biopsy was performed from the area if a suspicious lesion was found. Hematoxylin and eosin staining to determine histological changes and Warthin-Starry staining to examine H. pylori infection were performed simultaneously during mucosal biopsy. The diagnoses of upper GI cancer were confirmed histopathologically.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 and were statistically reviewed by a biomedical statistician. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patient demographics. Continuous variables were presented as the mean and standard deviation and the categorical data as number and percentage. The continuous variables were compared using the one-way ANOVA, and the categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-squared test. The histogram was implemented using the R package (v3.1).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between different risk factors with the presence of CSFs. The results were expressed as odds ratios along with 95% confidence interval (CI). P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

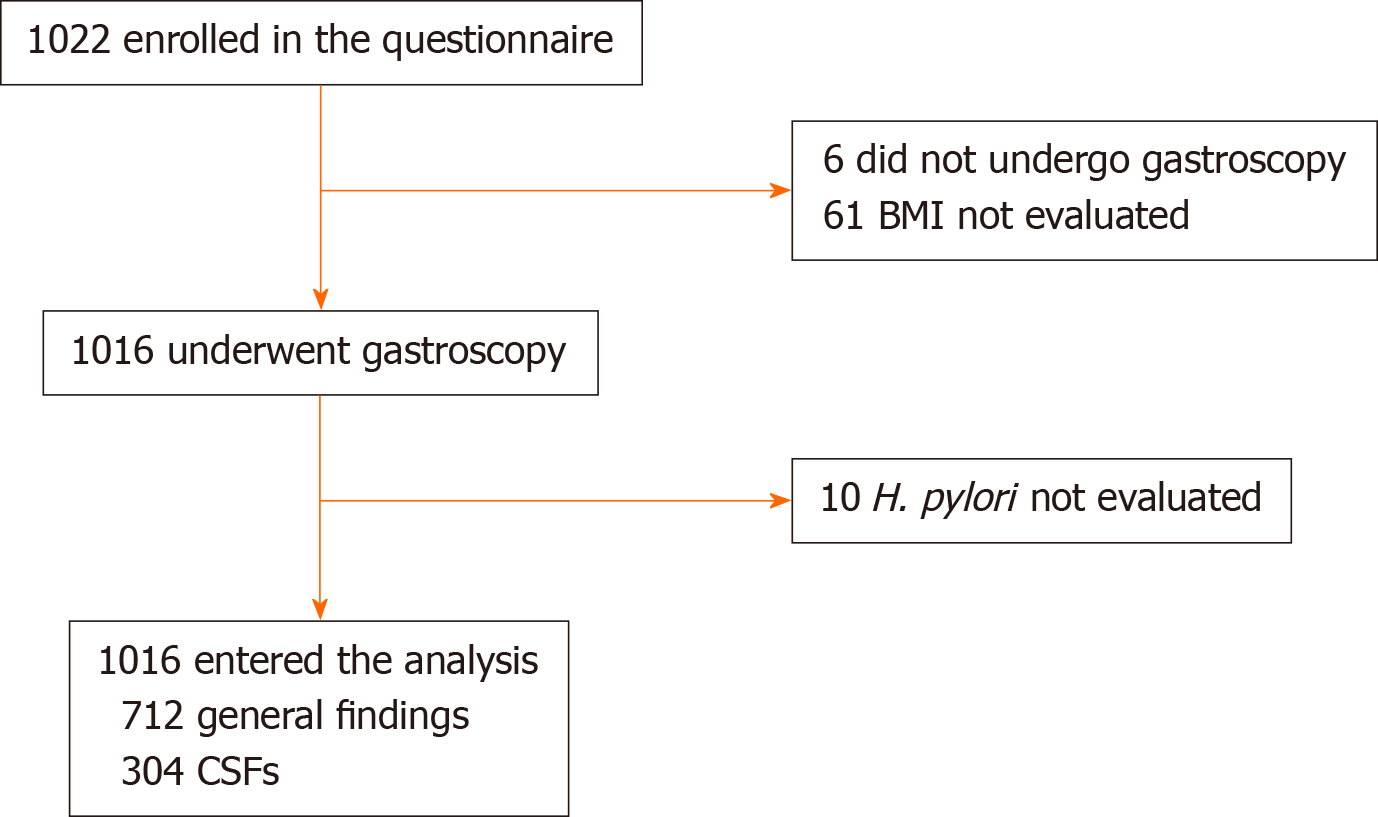

A total of 1016 cases were included, of which there were 376 (37.0%) males and 640 (63.0%) females (Figure 2). The mean age was 49.60 ± 15.36 years, and the mean BMI was 22.44 ± 3.66 kg/m2. The predominant symptoms were epigastric pain that was reported in 579 (57.0%) cases, epigastric burning in 353 (34.7%) cases, bloating in 672 (66.1%) cases, belching in 445 (43.8%) cases, early satiety in 221 (21.8%) cases and nausea in 230 (22.6%) cases (Table 1).

| Total, n = 1016 | General lesions, n = 712 | Esophageal lesions, n = 180 | Peptic ulcer, n = 115 | Malignancy, n = 9 | F value | χ2 value | P value | |

| Age | 49.60 ± 15.36 | 49.51 ± 15.20 | 52.22 ± 15.19 | 45.07 ± 15.44 | 62.33 ± 13.63 | 7.289 | < 0.001 | |

| Male | 376 (37.0) | 236 (33.1) | 82 (45.6) | 54 (47.0) | 4 (44.4) | 15.075 | 0.002 | |

| BMI | 22.44 ± 3.66 | 22.08 ± 3.18 | 23.47 ± 4.40 | 23.03 ± 4.43 | 23.88 ± 7.08 | 8.093 | 0.003 | |

| Epigastric pain | 579 (57.0) | 391 (54.9) | 102 (56.7) | 79 (68.7) | 7 (77.8) | 9.609 | 0.022 | |

| Epigastric burning | 353 (34.7) | 243 (34.1) | 61 (33.9) | 46 (40.0) | 3 (33.3) | 1.557 | 0.669 | |

| Bloating | 672 (66.1) | 471 (66.2) | 120 (66.7) | 73 (63.5) | 8 (88.9) | 2.883 | 0.410 | |

| Belching | 445 (43.8) | 316 (44.4) | 78 (43.3) | 47 (40.9) | 4 (44.4) | 0.519 | 0.915 | |

| Early satiety | 221 (21.8) | 158 (22.2) | 36 (20.0) | 26 (22.6) | 1 (11.1) | 1.157 | 0.763 | |

| Nausea | 230 (22.6) | 165 (23.2) | 38 (21.1) | 24 (20.9) | 3 (33.3) | 1.105 | 0.776 | |

| H. pylori positive | 253 (25.1) | 152 (21.5) | 33 (18.6) | 66 (57.9) | 2 (22.2) | 64.204 | < 0.001 |

The number of patients that had EPS, PDS, EPS-PDS were 267 (26.3%), 398 (39.2%) and 351 (34.5%), respectively (Table 2).

| Variables | EPS, n = 267 | PDS, n = 398 | EPS-PDS, n = 351 | F value | χ2 value | P value |

| Gender, male/female | 98/169 | 156/242 | 122/229 | 1.590 | 0.452 | |

| Age | 48.01 ± 16.21 | 50.94 ± 15.09 | 49.30 ± 14.90 | 3.025 | 0.049 | |

| BMI | 22.08 ± 3.27 | 22.62 ± 3.86 | 22.52 ± 3.69 | 1.746 | 0.175 | |

| CSFs | 97 (36.3) | 96 (24.1) | 111 (31.6) | 12.101 | 0.002 | |

| Esophageal lesions | 54 (20.2) | 63 (15.8) | 63 (17.9) | 2.138 | 0.343 | |

| Peptic ulcer | 40 (15.0) | 31 (7.8) | 44 (12.5) | 9.026 | 0.011 | |

| Malignancy | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1.1) | 1.184 | 0.553 | |

| H. pylori positive | 65 (24.5) | 101 (25.7) | 87 (25.0) | 0.122 | 0.941 |

The general findings were present in 712 (70.1%) cases. There were 479 (47.1%) cases of chronic superficial gastritis and 233 (22.9%) cases of chronic atrophic gastritis. The clinically significant endoscopic findings were observed in 304 (29.9%) patients that included esophageal lesions in 180 (17.7%) patients, peptic ulcer in 115 (11.3%) patients and malignancy in 9 (0.9%) patients. Between the 180 patients with esophageal lesions, 165 (16.2%) cases had reflux esophagitis [Los Angeles class A in 148 (14.6%) patients and Los Angeles classes B and C in 17 (1.7%) cases] and 5 (0.5%) patients had Barrett’s esophagus. In the peptic ulcer group, 49 (4.8%) cases had gastric ulcer, 44 (4.3%) cases had duodenal ulcer, and 22 (2.2%) cases had compound ulcers. The malignancy group included 8 (0.8%) cases of early gastroesophageal malignancy and 1 (0.10%) case of advanced gastric cancer (Table 3).

| Endoscopic diagnosis | n (%) |

| General lesions | 712 (70.1) |

| Chronic superficial gastritis | 479 (47.1) |

| Chronic atrophic gastritis | 233 (22.9) |

| Clinically significant findings | 304 (29.9) |

| Esophageal lesions | 180 (17.7) |

| Reflux esophagitis | 165 (16.2) |

| Los Angeles class A | 148 (14.6) |

| Los Angeles classes B and C | 17 (1.7) |

| Barrett’s esophagus | 5 (0.5) |

| Other esophageal lesions | 10 (1.0) |

| Peptic ulcer | 115 (11.3) |

| Gastric ulcer | 49 (4.8) |

| Duodenal ulcer | 44 (4.3) |

| Compound ulcer | 22 (2.2) |

| Malignancy | 9 (0.9) |

| Gastric cancer | 8 (0.8) |

| Esophageal cancer | 1 (0.1) |

The univariate analyses of clinical characteristics for patients with different endoscopic findings are given in Table 1. Further multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that males, BMI > 25, epigastric pain and H. pylori infection were independent risk factors for the presence of CSFs (odds ratio = 1.758, 1.660, 1.423, 1.949; 95% confidence interval: 1.312-2.356, 1.168-2.360, 1.060-1.909, 1.423-2.670, respectively; all P < 0.05, Table 4).

According to the pathology reports of all patients, the H. pylori positive rate was 25.1%. The peptic ulcer group had a significantly higher positive rate (57.9%) than other groups (P < 0.001; Table 1). In the PDS group, positive endoscopic findings were obtained in 96 (24.1%) patients, which was significantly lower than other groups (P = 0.002; Table 2).

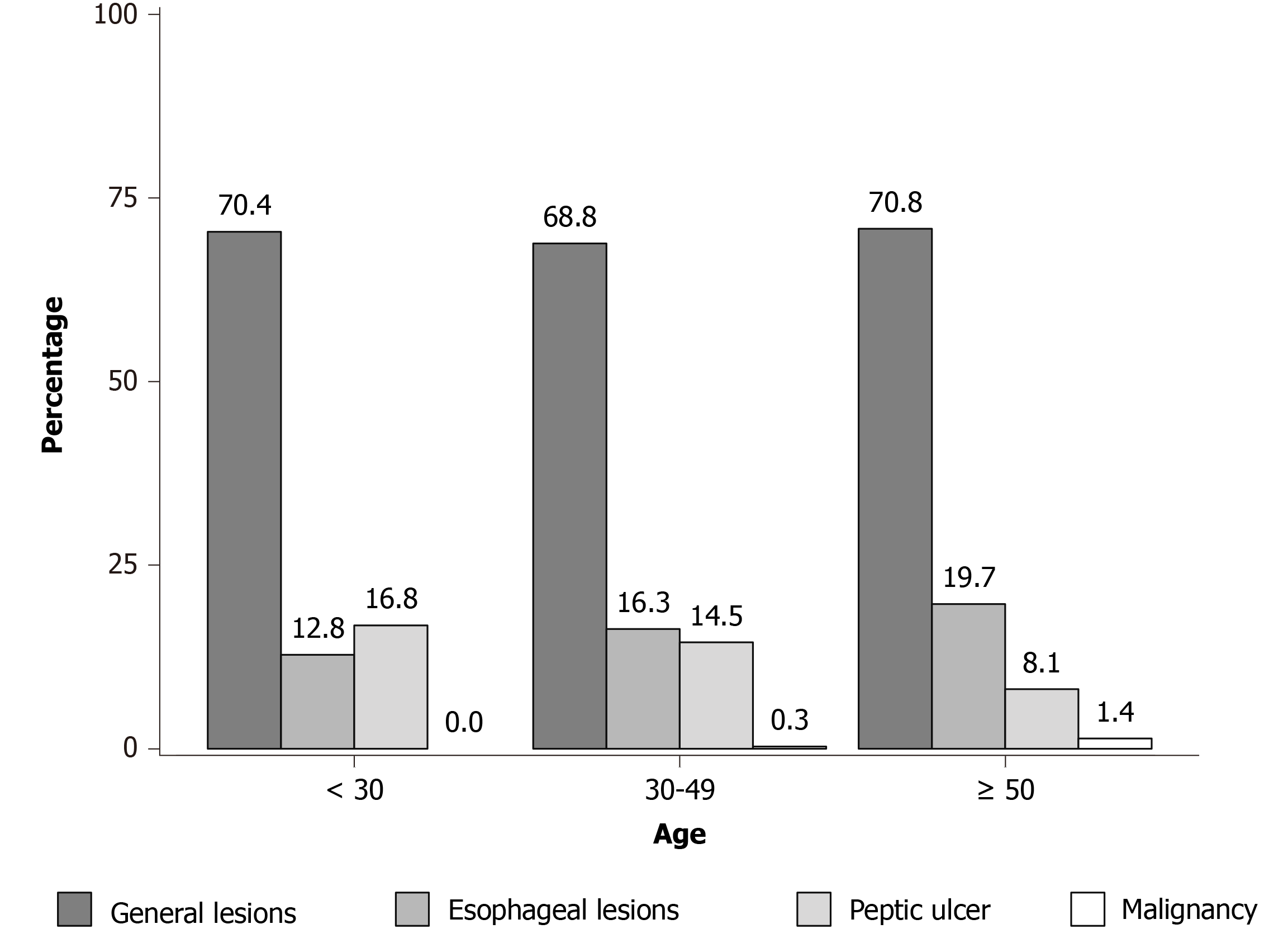

Between all the patients, 12.3% were < 30-years-old, 33.2% were 30-49-years-old, and 54.5% were ≥ 50-years-old. The proportions of general endoscopic findings, esophageal lesions, peptic ulcer and malignancy in the three age groups were significantly different (P = 0.004; Table 5). Although the constituent ratios of the esophageal diseases and early cancer increased with age between the three age subgroups, they did not reach statistical significance (Table 5, Figure 3).

| Age | Total (%) | General lesions (%) | Esophageal lesions (%) | Peptic ulcer (%) | Malignancy (%) | χ2 value | P value |

| < 30 | 125 (12.3) | 88 (70.4) | 16 (12.8) | 21 (16.8) | 0 (0.0) | 18.094 | 0.004 |

| 30-49 | 337 (33.2) | 232 (68.8) | 55 (16.3) | 49 (14.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| ≥ 50 | 554 (54.5) | 392 (70.8) | 109 (19.7) | 45 (8.1)a | 8 (1.4) |

Dyspepsia is one of the most frequently encountered clinical symptoms, which is present in approximately 2%-5% of the outpatients of primary care physicians[11,12]. However, uncertainty remains regarding the most appropriate initial management strategy for these patients, particularly for those patients with no warning symptoms.

To investigate whether endoscopy should be included in the initial treatment strategy for dyspeptic patients in China, the detection rates of significant endoscopic findings were analyzed in dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms, with a special focus on the prevalence of malignancy. Then, the association between upper GI symptoms and CSFs were investigated to determine the high-risk group of dyspeptic patients where the diagnostic result from endoscopy would be high.

In this study, the most common complaints were abdominal pain, bloating and belching. However, when dyspeptic patients did not have any warning symptoms the prevalence of CSFs in this study was approximately 29.9%, which is comparable with the result of similar previous studies[13]. In addition, a meta-analysis demonstrated that warning symptoms had a low positive predictive value for malignancy[14]. Therefore, due to the limited predictive ability of CSFs, warning symptoms should not be considered as an important element when clinical decisions are made for endoscopy.

In our study, the commonest CSFs included esophageal lesions (17.7%) and PUD (11.3%). Surprisingly, although most patients with esophageal disease did not complain of reflux or heartburn, the prevalence of reflux esophagitis was as high as 16.2%. However, most of these patients had Los Angeles class A esophagitis. For patients with PUD, the prevalence rate of H. pylori was 57.9% compared with 25.1% in all patients. In the noninvasive approach suggested in the guidelines of Western countries, if physicians can successfully manage PUD and erosive esophagitis and the prevalence of malignancy is low, then endoscopy may not be considered as the initial management strategy. However, in this study the prevalence of malignancy was 0.9%, which meant that approximately 1 in 100 dyspeptic patients had cancer and if endoscopy was not performed, then diagnosis would be delayed. In addition, most of the patients with+ dyspepsia that were diagnosed with cancer by endoscopy were in the early stages of disease, which made endoscopy more important to detect these early lesions.

Epigastric pain was present in a significant number of patients that had peptic ulcer (68.7%) or malignancy (77.8%). Additionally, bloating was frequently present in these patients. In the subgroups of dyspeptic patients with EPS and PDS, there was no significant difference between the endoscopic findings of these two syndromes, except for the patients with EPS had a higher prevalence of peptic ulcers. A study revealed that the accuracy of symptoms to predict the diagnosis of FD was only 17%[15]. Thomson et al[16] also observed that the predominant symptom was not predictive for endoscopic findings. Moreover, one study conducted in China showed that even warning symptoms had poor predictive value for organic dyspepsia and organic upper GI diseases[17]. In conclusion, the symptoms are of limited value in the assessment of dyspepsia.

Another objective of our study was to explore the risk factors associated with CSFs. Using multivariate analysis, male gender and H. pylori infection were significant predictors of CSFs, similar to that reported in previous studies[18,19]. In addition, studies have indicated that higher BMI (> 25) was associated with reflux esophagitis[20,21] and PUD, although the exact mechanism of the strong correlation was unclear[22]. This study showed that high BMI was crucial when predicting CSFs. The only symptom that was significantly associated with CSFs was epigastric pain (odds ratio = 1.423). This might be largely due to high acid secretion seen in patients with epigastric pain that increased the incidence of gastroesophageal injury[23].

Finally, a few studies have shown that age might play an important role in the diagnosis of CSFs[24,25]. A previous study concluded that the presence of any warning feature and age ≥ 55 were associated with a higher risk of CSFs[26]. However, in this study, the prevalence of CSFs did not increase with age, but the incidence of malignancy was relatively higher in patients ≥ 50 years of age. In this study, patients diagnosed with malignancy were all > 50 years old, except for a 42-year-old female patient. In other words, the proportion of dyspeptic patients < 50 years that had malignancy was only 0.1%. Therefore, for dyspeptic patients > 50-years-old, endoscopy should be performed to exclude malignancy even in the absence of warning symptoms. Additionally, the incidence of peptic ulcers gradually decreased with age. This could be due to the socioeconomic and work pressure that leads to stress, which is a known risk factor for peptic ulcers[27]. Interestingly, contrary to our results, a recent study showed a higher prevalence of gastric ulcers in people over 60 years of age[28]. However, their study covered all patients with dyspepsia who met the Rome IV criteria.

Many studies have shown that warning symptoms can hardly predict positive endoscopic findings. They concluded that gastroscopy should not be based solely on warning symptoms. Our study supports this from a different perspective. Overall, Chinese patients with dyspepsia should undergo gastroscopy regardless of the presence or absence of warning symptoms.

This study has a few limitations. First, this was a single center study, and not all patients were diagnosed with dyspepsia for the first time. In addition, the inclusion process and gastroscopic screening were mainly done by a few physicians, and therefore selection bias might occur. Secondly, our sample size was still not large enough to observe some trends that did not reach statistical significance. Therefore, future large, controlled studies with more indicators are needed to assess the long-term benefits of gastroscopy, such as setting up another cohort with warning symptoms to compare the value of gastroscopy in patients with these two types of dyspepsia.

Our study showed a high detection rate of CSFs in dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms under the Rome IV criteria. Gastroscopy has significant implications in dyspeptic patients, especially for those with independent risk factors. Therefore, gastroscopy should not be performed based on warning symptoms exclusively. Taken together, our study provided a basis for the development and progression of the initial treatment strategy for these patients.

Dyspepsia is a common clinical disorder. No studies have evaluated the diagnostic value of endoscopy in patients with no warning symptoms according to the Rome IV criteria.

Many studies have used warning symptoms to predict important endoscopic findings in patients with dyspepsia. However, there remains an uncertainty regarding the best initial management strategy for those patients with no warning features.

To evaluate the diagnostic value of endoscopy in dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms.

We performed a cross-sectional study of dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms from April 2018 to February 2019.

The incidence of malignancy (0.9%) among dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms was high. Moreover, male gender, body mass index > 25, epigastric pain and Helicobacter pylori infection were independently associated with significant endoscopic findings.

According to the Rome IV standard, endoscopy is of high diagnostic value for dyspeptic patients with no warning symptoms in China. Dyspeptic patients should undergo gastroscopy regardless of the presence or absence of warning symptoms.

Gastroscopy should be the initial management strategy for dyspeptic Chinese patients even in the absence of warning features. In the future, more controlled studies from multicenter samples will be needed to confirm this.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gram-Hanssen A, Noh AYM S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Knill-Jones RP. Geographical differences in the prevalence of dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991;182:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Epidemiology of functional dyspepsia: a global perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2661-2666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV-Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1257-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 731] [Cited by in RCA: 1036] [Article Influence: 115.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, Enns RA, Howden CW, Vakil N. ACG and CAG Clinical Guideline: Management of Dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:988-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 47.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Talley NJ. Dyspepsia: management guidelines for the millennium. Gut. 2002;50 Suppl 4:iv72-8; discussion iv79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zhao P, Zeng H, Zou X. Report of cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2010. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Eusebi LH, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2014;19 Suppl 1:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Jiang HL. Prevalence of and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese military personnel. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2013;21:4084. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moayyedi P, Duffett S, Braunholtz D, Mason S, Richards ID, Dowell AC, Axon AT. The Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire: a valid tool for measuring the presence and severity of dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1257-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, Tytgat GN, Wallin L. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1518] [Cited by in RCA: 1653] [Article Influence: 63.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Okumura T, Tanno S, Ohhira M. Prevalence of functional dyspepsia in an outpatient clinic with primary care physicians in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van Bommel MJ, Numans ME, de Wit NJ, Stalman WA. Consultations and referrals for dyspepsia in general practice--a one year database survey. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:514-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Clinically significant endoscopic findings in a multi-ethnic population with uninvestigated dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:3205-3212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vakil N, Moayyedi P, Fennerty MB, Talley NJ. Limited value of alarm features in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal malignancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:390-401; quiz 659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hammer J, Eslick GD, Howell SC, Altiparmak E, Talley NJ. Diagnostic yield of alarm features in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2004;53:666-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thomson AB, Barkun AN, Armstrong D, Chiba N, White RJ, Daniels S, Escobedo S, Chakraborty B, Sinclair P, Van Zanten SJ. The prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia: the Canadian Adult Dyspepsia Empiric Treatment - Prompt Endoscopy (CADET-PE) study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1481-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wei ZC, Yang Q, Yang J, Tantai XX, Xing X, Xiao CL, Pan YL, Wang JH, Liu N. Predictive value of alarm symptoms in patients with Rome IV dyspepsia: A cross-sectional study. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:4523-4536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hu PJ, Li YY, Zhou MH, Chen MH, Du GG, Huang BJ, Mitchell HM, Hazell SL. Helicobacter pylori associated with a high prevalence of duodenal ulcer disease and a low prevalence of gastric cancer in a developing nation. Gut. 1995;36:198-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wai CT, Yeoh KG, Ho KY, Kang JY, Lim SG. Diagnostic yield of upper endoscopy in Asian patients presenting with dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:548-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | El-Serag HB, Ergun GA, Pandolfino J, Fitzgerald S, Tran T, Kramer JR. Obesity increases oesophageal acid exposure. Gut. 2007;56:749-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, Kelly CP, Camargo CA Jr. Body-mass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2340-2348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 504] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang FW, Tu MS, Mar GY, Chuang HY, Yu HC, Cheng LC, Hsu PI. Prevalence and risk factors of asymptomatic peptic ulcer disease in Taiwan. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1199-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | McColl KE, Fullarton GM. Duodenal ulcer pain--the role of acid and inflammation. Gut. 1993;34:1300-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Eisen GM, Dominitz JA, Faigel DO, Goldstein JA, Kalloo AN, Petersen BT, Raddawi HM, Ryan ME, Vargo JJ 3rd, Young HS, Fanelli RD, Hyman NH, Wheeler-Harbaugh J; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The role of endoscopy in dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:815-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jung HK. Systematic Review With Meta-analysis: Prompt Endoscopy As the Initial Management Strategy for Uninvestigated Dyspepsia in Asi (Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:239-252). J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21:443-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Abdeljawad K, Wehbeh A, Qayed E. Low Prevalence of Clinically Significant Endoscopic Findings in Outpatients with Dyspepsia. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:3543681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Deding U, Ejlskov L, Grabas MP, Nielsen BJ, Torp-Pedersen C, Bøggild H. Perceived stress as a risk factor for peptic ulcers: a register-based cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Badi A, Naushad VA, Purayil NK, Chandra P, Abuzaid HO, Paramba F, Lutf A, Abuhmaira MM, Elzouki AY. Endoscopic Findings in Patients With Uninvestigated Dyspepsia: A Retrospective Study From Qatar. Cureus. 2020;12:e11166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |