Published online May 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3586

Peer-review started: February 4, 2021

First decision: March 7, 2021

Revised: March 17, 2021

Accepted: March 23, 2021

Article in press: March 23, 2021

Published online: May 26, 2021

Processing time: 96 Days and 8.7 Hours

Research data from patient reports indicate that the least bearable part of colonoscopy is the administration of laxatives for bowel preparation.

To observe the intestinal cleansing efficacy and safety of sodium picosulfate/magnesium citrate and to discuss the patients’ experiences due to the procedure.

Subjects hospitalized in the International Medical Center Ward of Peking University International Hospital, Beijing, China, from April 29 to October 29, 2020, for whom the colonoscopy was planned, were enrolled. Bowel preparation was performed using sodium picosulfate/magnesium citrate. The effect of bowel cleansing was evaluated according to the Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale, defecation conditions and adverse reactions were recorded, and the comfort level and subjective satisfaction concerning medication were evaluated by the visual analogue scale/score (VAS).

The bowel preparation procedure was planned for all patients enrolled, which included 42 males and 22 females. The results showed an average liquid rehydration volume of 3000 mL, an average onset of action for the first dose at 89.04 min, an average number of bowel movements of 4.3 following the first dose, an average onset of action for the second dose at 38.90 min and an average number of bowel movements of 5.0 after the second dose. The total average Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale score was 3.6, with 93.55% of bowel preparations in the “qualified” and 67.74% in the “excellent” grade. The average VAS score of effect on sleep was 0, and the average VAS score of perianal pain was also 0. The average VAS score for ease of taking and taste perception of the bowel cleanser was 10. Side effects included mild to moderate nausea (15.63%), mild vomiting (4.69%), mild to moderate abdominal pain (7.81%), mild to moderate abdominal distension (20.31%), mild palpitation (7.81%) and mild dizziness (4.69%).

Sodium picosulfate/magnesium citrate is effective and safe for bowel preparation before colonoscopy with high subjective patient acceptance, thus improving overall patient compliance.

Core Tip: At present, intestinal cleansers commonly used in clinical practice are not yet able to fully meet their ideal requirements including efficacy, safety, affordability, better patient tolerance and acceptance. In our research, the “qualified’ bowel preparation rate achieved with sodium picosulfate/magnesium citrate was 93.55%, whereas the “excellent’ rate was 67.74%. Age and a personal history of constipation are independent risk factors that affect the optimal bowel preparation rate. Furthermore, we performed a statistical analysis on defecation. The results showed a low incidence of adverse reactions and good palatability, thereby improving the overall bowel preparation experience and subsequent patient compliance.

- Citation: Liu FX, Wang L, Yan WJ, Zou LC, Cao YA, Lin XC. Cleansing efficacy and safety of bowel preparation protocol using sodium picosulfate/magnesium citrate considering subjective experiences: An observational study. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(15): 3586-3596

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i15/3586.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3586

With advances in endoscopy, colonoscopy has become indispensable in the screening, diagnosis and treatment of colon lesions[1,2]. The quality of bowel preparation is closely linked to the detection rates of colon lesions during colonoscopy. Meta-analysis has shown that low-quality bowel preparation significantly reduces the detection rate of adenomas, especially the detection rate of polyps ≤ 9 mm[3,4].

An ideal bowel preparation for colonoscopy should be safe, effective, well-tolerated and affordable. At present, a wide range of bowel cleansers are used including polyethylene glycol (PEG) electrolyte solution, magnesium sulfate, sodium phosphate and mannitol. However, none of these bowel cleansers can fully meet the requirements in clinical practice[5]. A prior study indicated that the administration of laxatives is the least bearable part of a colonoscopy[6]. Approximately 5%-15% of patients fail to complete the bowel preparation process due to the bad taste of the laxatives, the large volume intake and adverse events, such as abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting[7,8].

Sodium picosulfate/magnesium citrate (SPMC) is a dual-action laxative, which contains sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide and citric acid. Sodium picosulfate is an irritant laxative, whereas magnesium citrate formed from magnesium oxide and citric acid when dissolved in water is an osmotic laxative. As shown by the results of phase III clinical studies in Taiwan, China and the United States, SPMC was better in tolerability and acceptability than the 2 L PEG/bisacodyl combination among the patients receiving bowel preparation, and the efficacy and safety of SPMC was noninferior to that of PEG[9,10]. Even though SPMC was officially approved and used in China in 2019, few studies have been conducted on Chinese patients. Therefore, we were prompted to investigate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of SPMC in bowel preparation among Chinese patients. During this study, the defecation frequency, satisfaction, incidence and severity of adverse events and any risk factors affecting the quality of bowel preparation were assessed.

A total of 64 subjects (aged 18-75 years) who were hospitalized in the International Medical Center Ward of Peking University International Hospital, Beijing, China from April 29 to October 29, 2020 and for whom the colonoscopy was planned were recruited for the analysis. Patients with contraindications to colonoscopy, severe organ dysfunction, peptic ulcers, active inflammatory bowel disease, gastrointestinal obstruction or perforation, pregnant or breastfeeding were excluded. This trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University International Hospital, Beijing, China.

SPMC was administered as granules [produced by Ferring Pharmaceuticals (China) Co. Ltd. under the Picolax trade name; batch number: R15996A; ingredients: 10 mg sodium picosulfate, 3.5 g magnesium oxide, and 12 g citric acid per bag]. Patients had a low-residue diet for at least 1 d before the examination and fasted from 6:00 pm the day before the treatment. Prior to administration, one bag of SPMC was poured into 150 mL of cold water and stirred for 3 min to dissolve it. After 30 min, patients began to take the clear solution. The total amount of liquid intake required for consumption was adjusted to about 1.5 to 2 L at 500 mL/h according to bowel movement. At 4:00 am on the day of the examination, patients ingested another bag of SPMC and 1.5 L of clear liquid at 750 mL/h with the same procedure.

The Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale (OBPS) was used to evaluate the effect of bowel preparation. The rectum/sigmoid colon, transverse colon/descending colon and ascending colon/cecum were scored separately. Given the five grades from cleanest to most soiled (0-4 points) combined with the total colon fluid volume score (a small, medium and large amount giving 0, 1 and 2 points, respectively), the total score could range between 0-14 points. A score of ≤ 7 was considered “qualified”, while a score of ≤ 4 was considered “excellent” colon preparation[11]. Considering the high success rate and relatively low number of failures regarding the cleansing effect of laxative administration, the “excellent” bowel preparation rate was used as the endpoint of the efficacy of the protocol (Tables 1 and 2).

| Score | Description |

| 0 | Excellent: Clearly visible mucosal detail with almost no stool residue; any fluid present is clear with hardly any stool residue |

| 1 | Good: Some turbid fluid or stool residue, but mucosal detail still visible without the need for washing/suctioning |

| 2 | Fair: Some turbid fluid of stool residue obscuring mucosal detail; however, mucosal detail becomes visible with suctioning; washing not needed |

| 3 | Poor: Stool present obscuring mucosal detail and contour; a reasonable view is obtained by suctioning and washing |

| 4 | Inadequate: Solid stool obscuring mucosal detail, which cannot be cleared by washing and suctioning |

| Score | Description |

| 0 | Small volume of fluid |

| 1 | Moderate volume of fluid |

| 2 | Large volume of fluid |

Defecation frequency: The following data were recorded separately: The time of the first and second oral administration of SPMC; the time when drinking liquid was required after taking the medicine; the time when drinking liquid had to be stopped; the time of the first bowel movement; the time of the last bowel movement; the number of bowel movements; and the total volume of liquid taken.

Bowel preparation experience: The visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to evaluate the subjective patient satisfaction and comfort level, with a score ranging from 0 (very poor) to 10 (very good). Subjective satisfaction included the ease of taking medication and taste perception, whereas comfort level comprised perianal pain and the effect of treatment on sleep. If the patient was not receiving bowel preparation for the first time, medication used in the past and the corresponding taste perception were also recorded.

Adverse reactions: Undesirable side effects such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, bloating, palpitation, dizziness and other symptoms were recorded. Their degree was assessed during the bowel preparation.

Statistical methods: The continuous variables of normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD, and the independent samples t-test was used to compare the means between groups. Continuous variables of non-normal distribution were represented as median (minimum, maximum), and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for comparisons between groups. Categorical variables were expressed as rates or percentages, and the chi-square test was used for comparisons between groups. First, a single-factor logistic regression analysis was performed to determine significant risk factors, and a stepwise multivariate unconditional logistic regression analysis was performed on factors with P ≤ 0.10 to determine the independent risk factors that caused a lower than excellent bowel preparation rating (OBPS > 4). In this paper, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were completed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

A total of 64 patients (42 males and 22 females) with a mean age of 50 years were assessed. Of these, 32 cases had a body mass index > 25 kg/m2, and 32 cases had a body mass index ≤ 25 kg/m2 (Table 3). Forty-seven cases underwent colonoscopy for regular asymptomatic screening, a single patient had intermittent lower-left abdominal pain, 12 cases had a history of colonic polyps, 3 patients had chronic constipation, and 1 patient had chronic abdominal discomfort. Nine patients had a history of previous abdominal surgery of which three had undergone cholecystectomy, and one had undergone a cesarean section. A total of 42 patients underwent bowel preparation for the first time, and the previous bowel cleansers for the remaining patients were cleansers other than SPMC. Two subjects did not proceed with the colonoscopy after bowel preparation due to personal reasons.

| Characteristics | Study population, n = 64 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 42 (65.63) |

| Female | 22 (34.38) |

| BMI, mean, kg/m2 | 25.1 |

| BMI > 25 | 32 (50.00) |

| BMI ≤ 25 | 32 (50.00) |

| Constipation | 6 (9.38) |

| History of abdominal surgery | 9 (14.06) |

| Indication | |

| Screening | 47 (73.44) |

| History of colon polyp | 12 (18.75) |

| Chronic constipation | 3 (4.69) |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0.00) |

| Other | 2 (3.13) |

| History of past colonoscopy | 42 (65.63) |

The effect of bowel preparation was evaluated by OBPS. The average score for the ascending colon and cecum was 1.4, the average score for the transverse colon and descending colon was 0.9, the average score for the rectum and sigmoid colon was 0.8, and the average score for total colon fluid volume was 0.5. The average total score was 3.6. A high proportion (93.55%) of the bowel preparations were considered qualified (total score ≤ 7), and 67.74% of the bowel preparations were regarded as excellent (total score ≤ 4). Univariate analysis demonstrated that age and past occurrence of constipation may be related to the cleaning effect (P < 0.05) (Tables 4-6).

| Variables | Score |

| OBPS (mean) | |

| Ascending | 1.4 |

| Mid | 0.9 |

| Rectosigmoid | 0.8 |

| Total colon fluid | 0.5 |

| Overall (mean ± SD) | 3.6 ± 0.312 |

| Quality of bowel preparation, n (%) | |

| Success rate (OBPS ≤ 7) | 58 (93.55) |

| Excellence rate (OBPS ≤ 4) | 42 (67.74) |

| Polyp detection rate (%) | 36.9 |

| Supplementary water intake (mL) | 3000 (2250, 3800) |

| Sleep quality-VAS | 0 (0, 6) |

| Anal pain-VAS | 0 (0, 6) |

| Ease of drinking-VAS | 10 (4, 10) |

| Taste-VAS | 10 (5, 10) |

| Variables | Overall | OBPS ≤ 4, n = 42 | OBPS > 4, n = 20 | Statistics | P value |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 50.20 ± 10.36 | 47.90 ± 8.90 | 55.50 ± 11.90 | 2.81 | 0.0066 |

| Male | 41 (65.63) | 30 (71.40) | 11 (55.00) | 1.63 | 0.255 |

| BMI | 25.1 ± 4.0 | 25.4 ± 4.1 | 24.6 ± 3.9 | -0.68 | 0.4963 |

| ≤ 25 | 31 (50.00) | 19 (45.20) | 12 (60.00) | ||

| > 25 | 31 (50.00) | 23 (54.80) | 8 (40.00) | ||

| Constipation | 6 (9.38) | 1 (2.40) | 5 (25.00) | 7.9301 | 0.0112 |

| History of abdominal surgery | 9 (14.06) | 4 (9.50) | 5 (25.00) | 2.6151 | 0.133 |

| Taking drugs | 10 (15.63) | 5 (11.90) | 5 (25.00) | 1.7175 | 0.269 |

| Indications | 2.348 | 0.141 | |||

| Screening | 45 (72.58) | 33 (78.60) | 12 (60.00) | ||

| Other | 17 (27.42) | 9 (21.40) | 8 (40.00) | ||

| No history of past colonoscopy | 40 (65.63) | 29 (69.00) | 11 (55.00) | 1.1679 | 0.395 |

| Minutes from 1st dose of Picolax | |||||

| First stool | 73.0 (8, 243) | 86.7 (8, 243) | 98.2 (15, 230) | 0.7234 | 0.4694 |

| Last stool | 169.3 ± 96.8 | 175.0 ± 104.8 | 158.1 ± 79.4 | -0.64 | 0.5246 |

| Minutes from 2nd dose of Picolax | |||||

| First stool | 38.9 ± 28.1 | 37.8 ± 28.5 | 42.8 ± 28.5 | 0.65 | 0.5212 |

| Last stool | 139.5 ± 63.1 | 140.9 ± 56.0 | 137.9 | -0.18 | 0.8602 |

| Water intake (mL) | 3000.0 (2250, 3800) | 2989.3 (2250, 3000) | 2877.5 (2250, 3800) | 3.6245 | 0.0569 |

| Total frequency of defecation | 9.0 (5, 21) | 8.5 (5, 17) | 9.0 (5, 21) | 0.2819 | 0.779 |

| Sleep disturbances (VAS > 1) | 2.824 | 0.7271 | |||

| Yes | 20 | 15 (35.7) | 5 (25.0) | ||

| No | 42 | 27 (64.3) | 15 (75.0) | ||

| Ease of drinking | 0.01 | 1 | |||

| Easy (VAS ≥ 9) | 46 | 31 (73.8) | 15 (75.0) | ||

| Hard (VAS < 9) | 16 | 11 (26.2) | 5 (25.0) | ||

| Taste | 0.2214 | 1 | |||

| Satisfied (VAS ≥ 9) | 54 | 36 (85.7) | 18 (90.0) | ||

| Dissatisfied (VAS < 9) | 8 | 6 (14.3) | 2 (10.0) |

| Variable | Regression coefficient | SEM | Statistics | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Age | 0.0742 | 0.0299 | 6.1732 | 0.013 | 1.077 | 1.0160-1.1420 |

| Male (n, %) | 0.7156 | 0.5645 | 1.6071 | 0.2049 | 2.046 | 0.2677-6.1850 |

| Constipation | 2.6149 | 1.1362 | 5.2962 | 0.0214 | 13.665 | 1.4740-126.6990 |

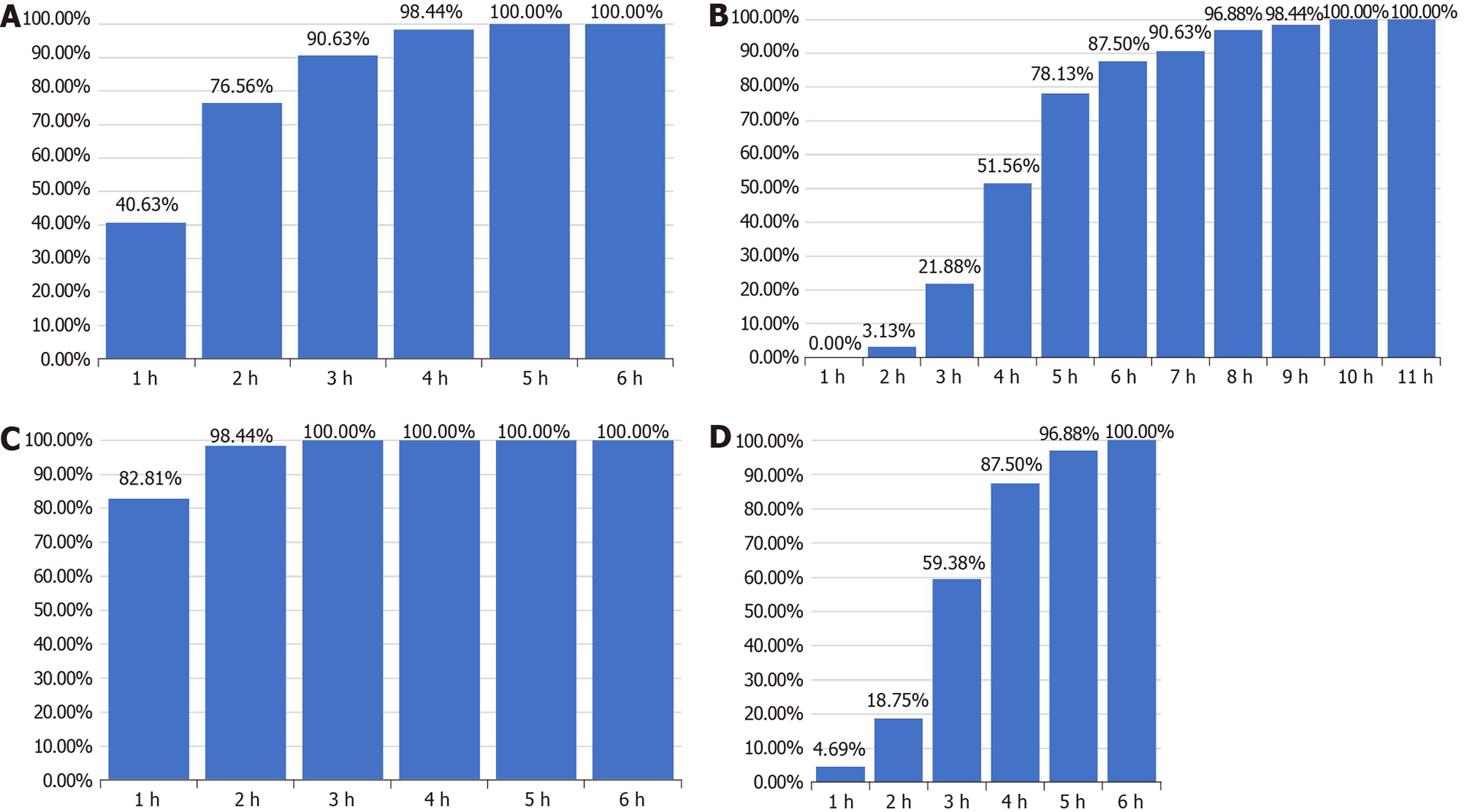

All 64 patients successfully completed the bowel preparation with an additional consumed volume of 3000 mL liquid. The average onset of action after the first dose was 89.04 min. The purgative took effect within 2 h in 76.56% (49/64) of patients, and 78.13% (50/64) of patients finished their last defecation within 5 h after first dose consumption. The average number of bowel movements following the first dose was 4.3. The second dose of purgative showed a more rapid onset of action with a shorter onset time on average (38.9 min) and higher proportion of patients receiving onset effects within 2 h (98.44%). The average bowel movements after the second dose was 5.0 (Table 5 and Figure 1).

The VAS score was used to evaluate the subjective satisfaction and comfort level of patients. Here, subjective satisfaction included ease of taking and taste perception. The median VAS score for ease of taking was 10, and the median VAS score for taste perception was 10. The average VAS score for the taste perception of previous bowel cleansers was 5.5 for 17 patients who had previously undergone bowel preparation. This was statistically significant compared to the taste perception score for the SPMC treatment (10) (P < 0.01). The assessment of comfort level included perianal pain and effect on sleep. The median VAS score for effect on sleep was 0, and the median VAS score for perianal pain was 0 (Table 4).

Data on undesirable side effects showed mild nausea in 8 cases (12.5%), moderate nausea in 2 cases (3.13%), mild vomiting in 3 cases (4.69%), mild abdominal pain in 4 cases (6.25%), moderate abdominal pain in one case (1.56%), mild abdominal distension in 11 cases (17.19%), moderate abdominal distension in 2 cases (3.13%), mild palpitation in 5 patients (7.81%) and mild dizziness in 3 patients (4.69%).

Due to the advancements in endoscopy technology[12-15], colonoscopy has become indispensable in the early screening, diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. The Expert Consensus on Early Diagnosis and Screening Strategies for Colorectal Tumors in China recommends people between 40 and 74 years of age to screen for early colorectal cancer[16]. Colonoscopy is regarded as the gold standard for the early diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Adequate bowel preparation ensures the accuracy of the examination[3]. A total of 93004 patients from the National Endoscopy Database were analyzed in a retrospective study in the United States, and only 71501 (76.9%) participants were found to have had satisfactory bowel preparation. In addition, it was shown that inadequate bowel preparation has a strong impact on the diagnosis of polyps ≤ 9 mm and other lesions[4]. According to the updated bowel preparation guidelines in China and Europe[5,17], endoscopists should evaluate bowel preparation efficiency during colonoscopy, and medical institutions should regularly monitor the eligibility of bowel preparation for subsequent procedures[16,17].

PEG electrolyte, a commonly used bowel cleanser in China, is an osmotic laxative that cleanses the intestine while necessitating the intake of large amounts of liquid orally[18,19]. Domestic studies have found that both the solution and powder of PEG electrolyte have good bowel cleansing effects, with “qualified” bowel preparation rates of 84.0% and 81.5%, respectively[20]. The rate of “qualified” bowel preparation achieved by a split-dose of 3 L of orally administered PEG electrolyte can reach 89.9%, while the “excellent” rate is 78.0%[21]. Research suggests that the rate of a “qualified” bowel preparation program involving 2 L of PEG electrolyte is 72.5%-90.6%[22-24]. Studies have shown that SPMC has equivalent or better intestinal cleansing effects than 2 L of PEG electrolyte[10]. Gao et al[25] conducted a self-controlled case series with patients who were administered enteric coated aspirin tablets for capsule endoscopy for an extended period and found that SPMC had the same bowel preparation effect as PEG electrolyte and was more readily accepted by patients[25].

In the present study, the “qualified” bowel preparation rate achieved by SPMC was 93.55%, whereas the “excellent” rate was 67.74%, which was similar to the results of other studies[26-30]. The generally accepted standard of criteria for eligibility for bowel preparation is the OBPS with scores ≤ 7[5]. Considering the small number (4 cases, 6.5%) of unqualified bowel preparations in this cohort, we used “excellent” bowel preparation (OBPS ≤ 4) as the grouping condition and performed simple and multiple logistic regression analysis. The results suggest that age and history of constipation are independent risk factors that affect the “excellent” bowel preparation rate. Prior research has suggested that patient education, a low-residue diet 3 d before endoscopy and other techniques may increase the “excellent” bowel preparation rate of SPMC in elderly patients and patients with previous constipation[5].

Due to the undesirable taste of bowel cleansers and the large liquid volume intake for wash-out, a median completion rate of bowel preparation for sodium phosphate of 97.0% (67%-100%) and a median completion rate for PEG electrolyte of 89.5% (53%-98%) were reported[31]. Even questionnaires have indicated that the main reason for patients not undergoing colonoscopy is a refusal to undergo the bowel preparation procedure[32-34]. Therefore, an increasing number of studies have focused on the intestinal cleanser administration experience. In the present study, all patients taking SPMC completed the bowel preparation procedure successfully and also rated a median VAS score of 10 for ease of taking and 10 for taste. Among the 22 patients who had previously undergone bowel preparation, the median VAS score for the taste of previous bowel cleansers (all non-SPMC) was 5.5, which was significantly lower than that of SPMC (10), (P < 0.01). Moreover, the average VAS score for disturbance to sleep in the SPMC group was 0, while the average VAS score for perianal pain was 0. These scores are comparable to those suggested by previous research results. It has been extensively reported that overall bowel preparation experience of SPMC is better than that of traditional laxatives because the taste is better[35]. According to the present study, a median volume of 3000 mL of clear fluid for rehydration can still provide ideal patient satisfaction and bowel preparation effects.

We further performed a statistical analysis on defecation frequency after SPMC administration to optimize the clinical guidance program. Our results show that the mean period of time from the first dose of SPMC to first bowel movement was 89.4 minutes. After the first dose of SPMC, 49 patients (76.57%) patients had the first bowel movement within 2 h, and 50 patients (78.13%) had the last bowel movement within 5 h. The average number of bowel movements after the first dose was 4.3. The mean period from the second dose of SPMC to the first bowel movement was 38.9 min. After the second dose of SPMC, 63 patients (98.44%) had the first bowel movements within 2 h, and 62 patients (96.89%) finished their last bowel movements within 5 h. Another study in children showed that the time from the first dose of SPMC to the first bowel movement was within 11 h, and the time to the last bowel movement was within 13 h. Also, the time period from the second SPMC dose to the first bowel movement was 2 h, and the last bowel movement was within 7 h[30]. Bowel preparation guidelines issued by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in 2019 recommended that the last bowel cleanser should be taken within 5 h before colonoscopy, and bowel preparation should be completed 2 h prior to the procedure. In summary, we suggest that the first dose of SPMC should be taken orally on the day before the examination and at least 5 h before going to bed to reduce its impact on sleep. Additionally, the second dose should be taken within 5 h before colonoscopy to obtain a better colon cleansing effect.

The common adverse reactions of bowel cleansers include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, bloating and headaches. As reported by previous research, patients taking SPMC for bowel preparation showed lower rates of adverse events than those of patients taking PEG (general malaise: 30% vs 49%; nausea: 20% vs 49%; vomit: 3% vs 20%). A number of studies also suggest no difference in the adverse reaction rates of SPMC compared with PEG[25]. A retrospective observational study of 147832 patients by Harewood et al[33] showed that both the SPMC group (n = 99237) and the PEG group (n = 48595) had a low incidence of adverse events, such as acute renal insufficiency and hypotension within 30 d after bowel preparation[33]. In this study, 15.63% of patients had mild to moderate nausea, 4.69% experienced mild vomiting, 7.81% suffered from mild to moderate abdominal pain and 20.31% were affected by mild to moderate abdominal distension. Taken together, these results suggest that SPMC has a lower incidence rate of adverse reactions and is safe for bowel preparation.

The limitation of the current study is that all participants were recruited from a single center with a relatively small sample size, which may affect the applicability of the results to a wider population. Therefore, we propose large-scale, prospective, randomized, controlled studies in the future to further confirm and explore the optimization of bowel preparation with SPMC.

In summary, we conclude that bowel preparation using SPMC achieves a highly qualified rating, a high rate of excellence, a low incidence of adverse reactions and good palatability, thereby improving the overall bowel preparation experience and subsequent patient compliance.

Bowel cleansing is important for successful colonoscopy, but the ideal clearing agent and volume are yet to be determined in China. A small-volume bowel cleansing agent is important for patient compliance. However, the general bowel preparation regimen in China is based on a large volume of polyethylene glycol.

In China, there is scarce evidence and few studies that observe the bowel cleansing effect of small-volume agents such as sodium picosulfate/magnesium citrate (SPMC). Therefore, to evaluate and optimize the use of SPMC is of important significance for improving patient tolerability during colonoscopy.

We observed bowel cleansing effectiveness and safety as well as patient-centered clinical characteristics, such as the pattern of defecation, acceptance and tolerability during bowel preparation.

We included patients who were hospitalized and underwent colonoscopy from April 29 to October 29, 2020. Subjects received SPMC as a bowel cleansing agent. The bowel cleansing effect was evaluated according to the Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale (OBPS). Defecation conditions and adverse reactions were recorded. The comfort level and subjective satisfaction towards medication were evaluated by the visual analogue scale/score (VAS).

A total of 64 subjects receiving SPMC were included in the study. The rate of successful bowel preparation (OBPS ≤ 7) was 93.55% in this cohort, with 67.74% showing “excellent” bowel preparation (OBPS ≤ 4). Although the median additional liquid volume was 3000 mL, the median visual analogue score for ease of taking and taste perception of the bowel cleanser was excellent, indicating a well-tolerated profile of SPMC. Univariate analysis and logistic regression analysis for subjects with OBPS > 4 indicated that age and previous constipation were risk factors for a suboptimal bowel cleansing effect.

The present study indicates that sodium picosulfate with magnesium citrate provides optimal bowel cleansing effects as well as a more positive patient experience regardless of whether they had had a previous colonoscopy experience or not. Enhanced bowel preparation should be considered in elderly patients and constipated patients to improve the bowel cleansing effect.

The present study is the first large-sample, observational study on patient-centered clinical characteristics after SPMC administration in China, providing evidence for clinical treatment and clinical guidance for subsequent randomized controlled studies.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gruber S S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Shi T, Feng X, Jie Z. Progress and Current Status of Influenza Researches in China. J Transl Int Med. 2019;7:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Djiambou-Nganjeu H. Relationship Between Portal HTN and Cirrhosis as a Cause for Diabetes. J Transl Int Med. 2019;7:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Clark BT, Rustagi T, Laine L. What level of bowel prep quality requires early repeat colonoscopy: systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of preparation quality on adenoma detection rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1714-23; quiz 1724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Digestive Endoscopy Special Committee of Endoscopic Physicians Branch of Chinese Medical Association; Cancer Endoscopy Committee of China Anti-Cancer Association. [Chinese guideline for bowel preparation for colonoscopy (2019, Shanghai)]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2019;58:485-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McLachlan SA, Clements A, Austoker J. Patients' experiences and reported barriers to colonoscopy in the screening context--a systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:137-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kang X, Zhao L, Zhu Z, Leung F, Wang L, Wang X, Luo H, Zhang L, Dong T, Li P, Chen Z, Ren G, Jia H, Guo X, Pan Y, Fan D. Same-Day Single Dose of 2 Liter Polyethylene Glycol is Not Inferior to The Standard Bowel Preparation Regimen in Low-Risk Patients: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:601-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bitoun A, Ponchon T, Barthet M, Coffin B, Dugué C, Halphen M; Norcol Group. Results of a prospective randomised multicentre controlled trial comparing a new 2-L ascorbic acid plus polyethylene glycol and electrolyte solution vs. sodium phosphate solution in patients undergoing elective colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1631-1642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hung SY, Chen HC, Chen WT. A Randomized Trial Comparing the Bowel Cleansing Efficacy of Sodium Picosulfate/Magnesium Citrate and Polyethylene Glycol/Bisacodyl (The Bowklean Study). Sci Rep. 2020;10:5604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rex DK, Katz PO, Bertiger G, Vanner S, Hookey LC, Alderfer V, Joseph RE. Split-dose administration of a dual-action, low-volume bowel cleanser for colonoscopy: the SEE CLEAR I study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:132-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kaminski MF, Thomas-Gibson S, Bugajski M, Bretthauer M, Rees CJ, Dekker E, Hoff G, Jover R, Suchanek S, Ferlitsch M, Anderson J, Roesch T, Hultcranz R, Racz I, Kuipers EJ, Garborg K, East JE, Rupinski M, Seip B, Bennett C, Senore C, Minozzi S, Bisschops R, Domagk D, Valori R, Spada C, Hassan C, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Rutter MD. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) quality improvement initiative. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:309-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Guo J, Li H, Chen Y, Chen P, Li X, Sun S. Robotic ultrasound and ultrasonic robot. Endosc Ultrasound. 2019;8:1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Artifon ELA, Visconti TAC, Brunaldi VO. Choledochoduodenostomy: Outcomes and limitations. Endosc Ultrasound. 2019;8:S72-S78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cazacu IM, Udristoiu A, Gruionu LG, Iacob A, Gruionu G, Saftoiu A. Artificial intelligence in pancreatic cancer: Toward precision diagnosis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2019;8:357-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ohno E, Hirooka Y, Kawashima H, Ishikawa T. Feasibility of EUS-guided shear-wave measurement: A preliminary clinical study. Endosc Ultrasound. 2019;8:215-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chinese Anti-Cancer Association Colorectal Cancer Professional Committee China Colorectal Tumor Early Diagnosis and Screening Strategies Expert Group. Expert Consensus on Chinese Colorectal Tumor Early Diagnosis and Screening Strategies. Zhonghua Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2018;21:1081-1086. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Hassan C, East J, Radaelli F, Spada C, Benamouzig R, Bisschops R, Bretthauer M, Dekker E, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ferlitsch M, Fuccio L, Awadie H, Gralnek I, Jover R, Kaminski MF, Pellisé M, Triantafyllou K, Vanella G, Mangas-Sanjuan C, Frazzoni L, Van Hooft JE, Dumonceau JM. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:775-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 18. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF, Early DS, Muthusamy VR, Khashab MA, Chathadi KV, Fanelli RD, Chandrasekhara V, Lightdale JR, Fonkalsrud L, Shergill AK, Hwang JH, Decker GA, Jue TL, Sharaf R, Fisher DA, Evans JA, Foley K, Shaukat A, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Wang A, Acosta RD. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:781-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, Robertson DJ, Boland CR, Giardello FM, Lieberman DA, Levin TR, Rex DK; US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:903-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhan J, Tang JZ, Wang WS, Xia XM, Tang M. Comparison of different dosage forms of polyethylene glycol electrolytes in the bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Zhonghua Quanke Yixue. 2020;18:1823-1826. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Zhang S, Li M, Zhao Y, Lv T, Shu Q, Zhi F, Cui Y, Chen M. 3-L split-dose is superior to 2-L polyethylene glycol in bowel cleansing in Chinese population: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ell C, Fischbach W, Bronisch HJ, Dertinger S, Layer P, Rünzi M, Schneider T, Kachel G, Grüger J, Köllinger M, Nagell W, Goerg KJ, Wanitschke R, Gruss HJ. Randomized trial of low-volume PEG solution vs standard PEG + electrolytes for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:883-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kelly NM, Rodgers C, Patterson N, Jacob SG, Mainie I. A prospective audit of the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of low-volume polyethylene glycol (2 L) vs standard volume polyethylene glycol (4 L) vs magnesium citrate plus stimulant laxative as bowel preparation for colonoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:595-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Corporaal S, Kleibeuker JH, Koornstra JJ. Low-volume PEG plus ascorbic acid vs high-volume PEG as bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1380-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gao Y, Gao F, Zhang L. Comparison of the effects of two bowel preparation methods in capsule endoscopy in patients taking aspirin enteric-coated tablets. Zhongguo Yiyao. 2020;15:915-918. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Flemming JA, Vanner SJ, Hookey LC. Split-dose picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and citric acid solution markedly enhances colon cleansing before colonoscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:537-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hamilton D, Mulcahy D, Walsh D, Farrelly C, Tormey WP, Watson G. Sodium picosulphate compared with polyethylene glycol solution for large bowel lavage: a prospective randomised trial. Br J Clin Pract. 1996;50:73-75. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Saunders BP, Masaki T, Fukumoto M, Halligan S, Williams CB. The quest for a more acceptable bowel preparation: comparison of a polyethylene glycol/electrolyte solution and a mannitol/Picolax mixture for colonoscopy. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71:476-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Regev A, Fraser G, Delpre G, Leiser A, Neeman A, Maoz E, Anikin V, Niv Y. Comparison of two bowel preparations for colonoscopy: sodium picosulphate with magnesium citrate vs sulphate-free polyethylene glycol lavage solution. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1478-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Turner D, Benchimol EI, Dunn H, Griffiths AM, Frost K, Scaini V, Avolio J, Ling SC. Pico-Salax vs polyethylene glycol for bowel cleanout before colonoscopy in children: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1038-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: oral bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:373-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Denberg TD, Melhado TV, Coombes JM, Beaty BL, Berman K, Byers TE, Marcus AC, Steiner JF, Ahnen DJ. Predictors of nonadherence to screening colonoscopy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:989-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Melton LJ 3rd. A prospective, controlled assessment of factors influencing acceptance of screening colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3186-3194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Seeff LC, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, Thompson T, Shapiro JA, Vernon SW, Coates RJ. Patterns and predictors of colorectal cancer test use in the adult U.S. population. Cancer. 2004;100:2093-2103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Jin Z, Lu Y, Zhou Y, Gong B. Systematic review and meta-analysis: sodium picosulfate/magnesium citrate vs. polyethylene glycol for colonoscopy preparation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72:523-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |