Published online May 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3576

Peer-review started: January 4, 2021

First decision: January 23, 2021

Revised: January 28, 2021

Accepted: April 8, 2021

Article in press: April 8, 2021

Published online: May 26, 2021

Processing time: 127 Days and 2.5 Hours

The surge of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients has markedly influenced the treatment policies of tertiary hospitals because of the need to protect medical staff and contain viral transmission, but the impact COVID-19 had on emergency gastrointestinal endoscopies has not been determined.

To compare endoscopic activities and analyze the clinical outcomes of emergency endoscopies performed before and during the COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu, the worst-hit region in South Korea.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted on patients aged ≥ 18 years that underwent endoscopy from February 18 to March 28, 2020, at a tertiary hospital in Daegu. Demographics, laboratory findings, types and causes of emergency endoscopies, and endoscopic reports were reviewed and compared with those obtained for the same period in 2018 and 2019.

From February 18 to March 28, a total of 366 emergent endoscopic procedures were performed: Upper endoscopy (170, 50.6%), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (113, 33.6%), and colonoscopy with sigmoidoscopy (53, 15.8%). The numbers of procedures performed in 2018 and 2019 dropped by 48.8% and 54.8%, respectively, compared with those in 2020. During the COVID-19 outbreak, the main indications for endoscopy were melena (36.7%), hematemesis (30.6%), and hematochezia (10.2%). Of the endoscopic abnormalities detected, gastrointestinal bleeding was the most common: 39 cases in 2018, 51 in 2019, and 35 in 2020.

The impact of COVID-19 is substantial and caused dramatic reductions in endoscopic procedures and changes in patient behaviors. Long-term follow-up studies are required to determine the effects of COVID-19 induced changes in the endoscopy field.

Core Tip: This is the first East Asian report to be issued on the impacts of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on emergent endoscopic activities and outcomes. This study demonstrated significant reductions in endoscopic procedures and changes in patient behaviors during the specific period (February 18 to March 28, 2020), from the start of the outbreak to the plateau of its exponential curve, in Daegu (South Korea), the worst-hit city, during the COVID-19 outbreak. We compared the changes in the numbers of endoscopic modalities and analyzed the causes and clinical outcomes of emergency endoscopies performed before (2018, 2019) and during the COVID-19 outbreak.

- Citation: Kim KH, Kim SB, Kim TN. Changes in endoscopic patterns before and during COVID-19 outbreak: Experience at a single tertiary center in Korean. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(15): 3576-3585

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i15/3576.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3576

A deadly coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan city (China) in 2019 was identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the associated disease was entitled as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)[1,2]. After the outbreak in China at the end of 2019, COVID-19 exponentially affected countries around the world and reached pandemic. COVID-19 also caused a paradigm shift in the medical practices of clinics and tertiary hospitals. However, the impact of COVID-19 in the gastrointestinal field is not fully understood. To meet the challenges posed by the pandemic, the American Society of Gastroenterology Endoscopy, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the Asian Pacific Society for Digestive Endoscopy, and the Japanese Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society presented guidelines on safe endoscopy[3-6]. From the perspective of gastroenterologists, the prevention of viral dissemination associated with endoscopy is a primary concern. Although it is recognized that COVID-19 is transmitted primarily via the respiratory tract, endoscopists face the risk of transmission via fecal and oral routes[2,7-9].

After the first report of reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection on February 18, 2020, an explosive increase in the number of COVID-19 cases occurred in Daegu, South Korea, at the end of February. Cumulative cases totaled 6587 by March 28, and new daily cases peaked at 740 on February 29[10,11]. Endoscopy involves direct contact with body fluid, oropharyngeal mucosa and fecal fluid. In addition, endoscopic procedures can be covert vectors of transmission due to the risk of aerosol formation by coughing[12-14]. Moreover, it has also been reported that SARS-CoV-2 can survive in the gastrointestinal tract for more than 2 wk[2]. Because of the importance of protecting medical staff and patients in endoscopy centers and emergency rooms[3,4], most elective endoscopies were canceled or postponed at our hospital due to the implementation of a strict infection control policy[3], which resulted in a substantial decrease in the number of endoscopic procedures[15].

This study was undertaken to compare and analyze changes in the numbers of endoscopic modalities and the causes and clinical outcomes of emergency endoscopies performed before and during the COVID-19 outbreak.

This retrospective cohort study was performed on all patients aged ≥ 18 years that underwent endoscopy from February 18 to March 28, 2020, that is, from the start of the outbreak to the plateau of its exponential curve, at a tertiary teaching hospital in Daegu City, the epicenter of the initial COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. Demographic data, laboratory data, chief complaints, types of endoscopies, causes of emergent endoscopies, and endoscopic reports for the above-mentioned period and the same periods in 2018 and 2019 were collected and reviewed. Endoscopic ultrasound was excluded from this study because it is commonly indicated for non-urgent evaluations. A summary of the endoscopic procedures performed from February 18 to March 29 in this three-year study is provided. Written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yeungnam University Medical Center.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, all emergency room (ER) visitors had to follow a strict COVID-19 quarantine process before entering the ER to minimize the nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2. All visitors were directly sent to a walk-in screening clinic and questioned about respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, fever, and sore throat) and any history of exposure to COVID-19 patients. In addition, all were tested for COVID-19 by RT-PCR using throat and nose swabs and had to wait for around 6 h for results. In RT-PCR positive cases, endoscopy was deferred until a negative result was obtained, unless an urgent endoscopic procedure was needed. Unfortunately, at that time, no practical guideline had been issued regarding means of protecting patients or health care providers (HCPs) from COVID-19 infection either in ERs or endoscopic rooms in Korea. During endoscopy, all HCPs were fully protected with personal protective equipment, which included N95 masks, disposable gowns, gloves, and facial shields in accord with level C protection. In particular, extreme vigilance was exercised during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)[16,17].

Clinically, documentation of COVID infection is challenging due to its long incubation time. To prevent endoscopy-related SARS-CoV-2 transmission, multi-step processing of flexible endoscopes requires high-level bactericidal, mycobactericidal, fungicidal, and virucidal disinfection, based on the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline[16,18].

Numbers and causes of elective or emergency endoscopy, endoscopic findings, and interventions were analyzed for each study year, and results were compared. Continuous variables are presented as means ± SD. Fisher’s exact test and one-way analysis of variance were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Differences with a P value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistic Package for Social Science version 21 (SPSS, Incorporated, Chicago, IL, United States).

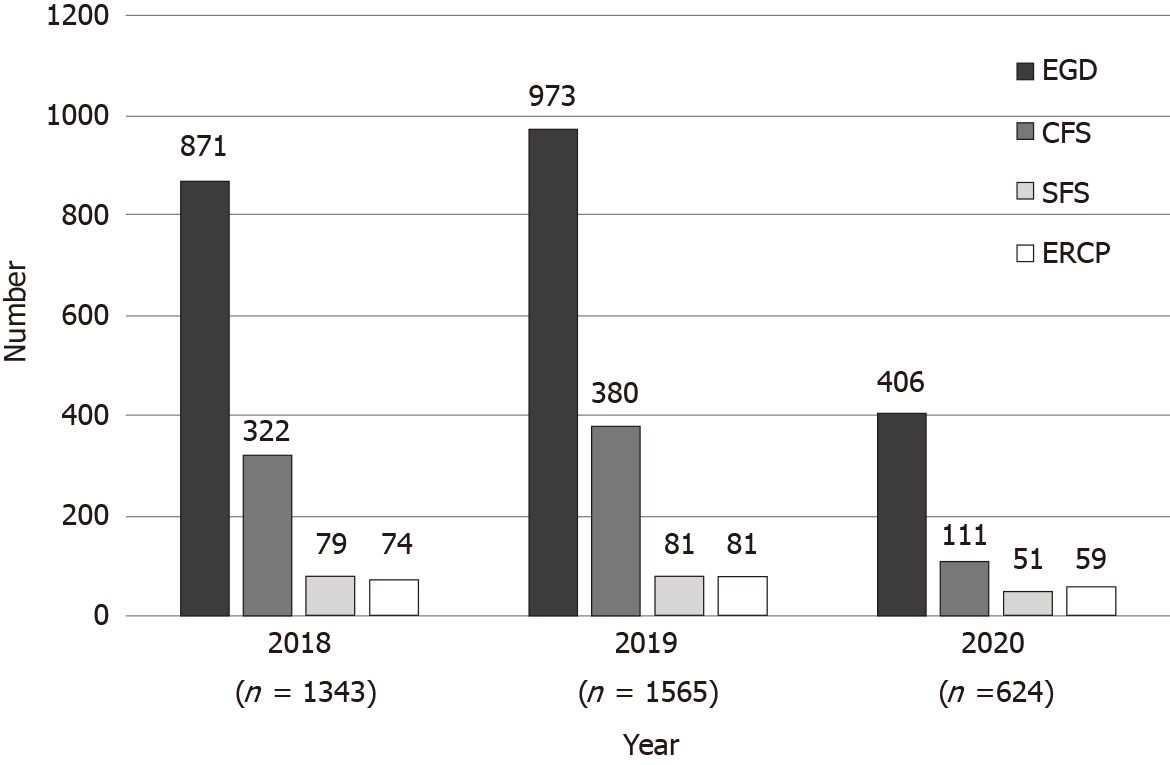

The number of endoscopies performed from February 18 to March 28 in 2018 and 2019 were 1343 and 1565, respectively (Figure 1), and the number of endoscopies performed in 2020 were 53.5% and 60.1% lower than in 2018 and 2019, respectively (P < 0.01). In 2020, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was most commonly performed (n = 406, 65.1%), followed by colonoscopy (n = 110, 17.6%), ERCP (n = 59, 9.5%), and sigmoidoscopy (n = 49, 7.9%) (Figure 1).

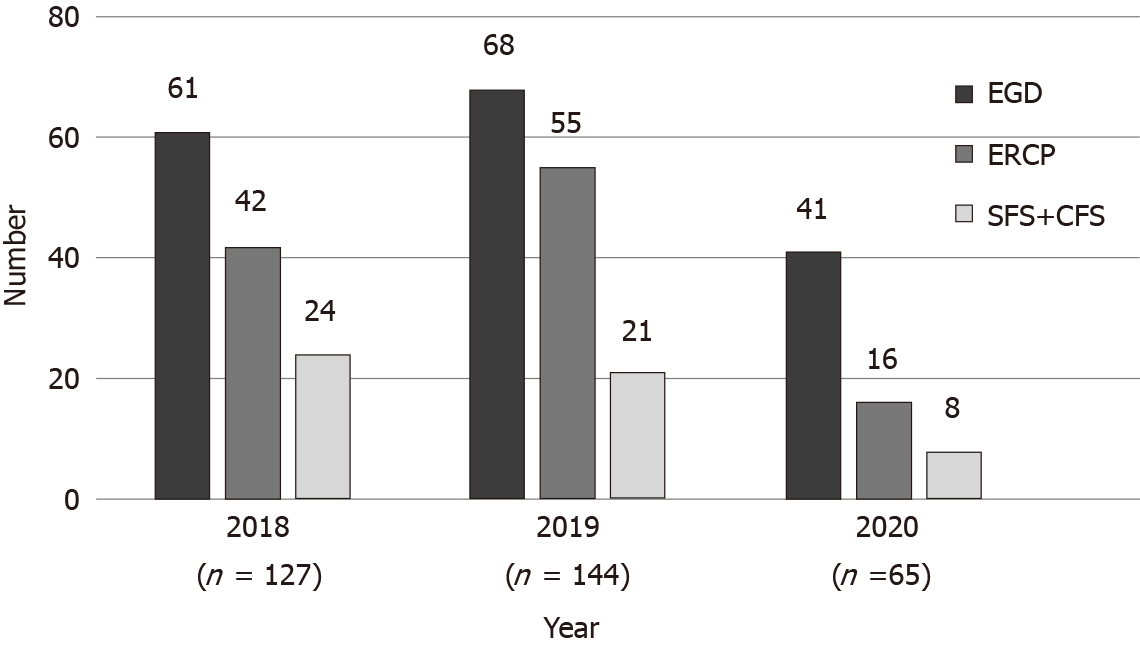

During the three study years, a total of 366 emergent endoscopic procedures were performed: 170 (50.6%) EGDs, 113 (33.6%) ERCPs, and 53 (15.8%) colonoscopies with sigmoidoscopy. Of these 336 procedures, 127 and 144 were performed in 2018 and 2019, respectively (Figure 2), and these numbers dropped noticeably in 2020 by 48.8% and 54.8% as compared with those in 2018 and 2019, but without statistical significance. Mean age of the 65 patients treated in 2020 was 68.2 ± 14.0 years (range 24-95) and 35 (53.8%) were male. Only one patient was confirmed to be SARS-CoV-2 positive. In 2020, EGD was most frequently performed (n = 41, 63.1%), followed by ERCP (n = 16, 24.6%) and sigmoidoscopy with colonoscopy (n = 8, 12.3%).

The most common indication for emergency endoscopy among the 336 cases was abdominal pain (n = 98, 29.2%), followed by melena (n = 84, 25.0%), hematemesis (n = 44, 13.1%), hematochezia (n = 38, 11.3%), anemia (n = 26, 7.7%), jaundice (n = 14, 4.2%), fever (n = 13, 3.9%), and foreign body ingestion (n = 8, 2.4%). Other indications were diarrhea (n = 3), acute drug intoxication (n = 3), emergent kidney transplantation donor evaluation (n = 4), and dyspnea (n = 1). A total of 113 ERCPs were performed, and of these, abdominal pain (n = 86, 76.1%) was the leading indication, followed by jaundice (n = 14, 12.4%) and fever (n = 13, 11.5%).

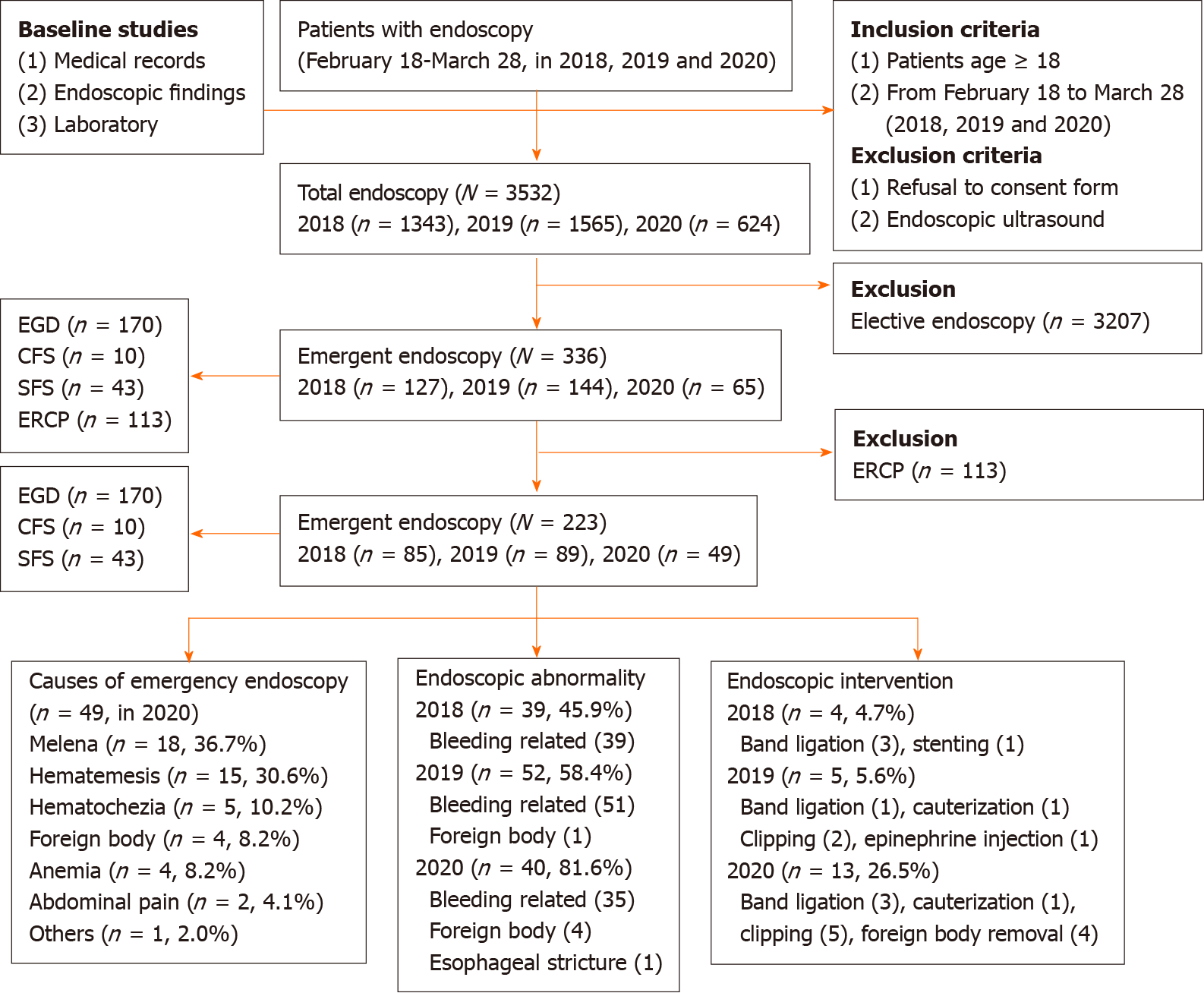

After excluding 113 ERCP cases, 223 cases were further analyzed to investigate the non-biliary causes of emergent endoscopies. Of these 223 cases, 49 endoscopies were conducted in 2020, which represented an approximately 40% reduction as compared with 2018 (n = 85) and 2019 (n = 89) (Table 1). During the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, the chief indications for endoscopy were melena (n = 18, 36.7%), followed by hematemesis (n = 15, 30.6%), hematochezia (n = 5, 10.2%), anemia (n = 4, 8.2%), foreign body ingestion (n = 4, 8.2%), and abdominal pain (n = 2, 4.1%). A flowsheet for all endoscopic procedures is illustrated in Figure 3. Endoscopic abnormalities included esophageal ulcer or stricture, esophageal foreign body, gastric or duodenal ulceration, gastric or colon malignancy, colon polyps, varices, angiodysplasia, colitis, small bowel bleeding, and a Mallory-Weiss tear. Of 131 endoscopic abnormalities, 39 (45.9%) were found in 2018, 52 (58.4%) in 2019, and 40 (81.6%) in 2020 (Table 2 and Figure 3). Of the 40 endoscopic abnormalities encountered in 2020, a presumed gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB)-related lesion was observed in 35 cases (45.9%), foreign body ingestion in 4 (8.2%), and esophageal ulcer with stricture due to acute drug intoxication in 1 (2.0%). Regarding anemia, mean hemoglobin level was 8.1 ± 2.2 g/dL (range 4.8-16.5) during the COVID-19 outbreak, but significantly higher in 2018 (9.8 ± 3.2 g/dL) and 2019 (8.8 ± 2.7 g/dL) (P < 0.001). In terms of endoscopic intervention, a total of 22 patients underwent endoscopic treatment during the three study years. Of the 13 cases treated in 2020, endoscopic clipping was performed in 5, foreign body removal in 4, band ligation of esophageal varices in 3, and cauterization in 1 (Figure 3). No case of endoscopy-related COVID-19 infection of medical workers or patients occurred at our endoscopic center.

| Variables | Year | |||

| 2018 (n = 85) | 2019 (n = 89) | 2020 (n = 49) | Total (n = 223) | |

| Melena | 28 (32.9) | 39 (43.8) | 18 (36.7) | 85 (38.1) |

| Hematemesis | 18 (21.2) | 10 (11.2) | 15 (30.6) | 43 (19.3) |

| Hematochezia | 21 (24.7) | 13 (14.6) | 5 (10.2) | 39 (17.5) |

| Anemia | 8 (9.4) | 13 (14.6) | 4 (8.2) | 25 (11.2) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (1.2) | 9 (10.1) | 2 (4.1) | 12 (5.4) |

| Foreign body | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.2) | 4 (8.2) | 8 (3.6) |

| Others | 7 (8.2) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (2.0) | 11 (4.9) |

| Variables | Year | |||

| 2018 (n = 85) | 2019 (n = 89) | 2020 (n = 49) | P value | |

| Endoscopic abnormality | 39 (45.9) | 52 (58.4%) | 40 (81.6) | < 0.001 |

| Endoscopic intervention | 4 (4.7) | 5 (5.6) | 13 (26.5) | < 0.0011 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.8 ± 3.2 (4.8-16.5) | 8.8 ± 2.7 (3.6-15.9) | 8.1 ± 2.2 (4.8-16.5) | 0.003 |

In February 2020, no practical guideline was available for the management of suspicious or confirmed COVID-19 patients requiring emergency endoscopy in Korea. When an ER patient was confirmed to be SARS-CoV-2 positive, the task-force committee of Daegu metropolitan city decided that the ER be immediately closed for 24 h to prevent viral transmission. Later this policy was modified to allow the ER to function as soon as possible after full disinfection. Recently, we proposed a practical algorithm for emergency endoscopy to address the challenges posed by COVID-19 and described personal protective equipment usage and the sequential process from initial screening to endoscopy[19].

Numerous articles regarding endoscopic practice before and after lockdown due to COVID-19 have been published, mostly in Europe and the United States[14,15]. In the present study, we analyzed and compared endoscopic patterns before (2018, 2019) and during the COVID pandemic at a tertiary hospital located in Daegu (South Korea), which was located at the epicenter of the first serious outbreak. An Italian study reported that 65% of endoscopic units had to modify endoscopy procedures and perform endoscopies in operating rooms, wards, or ERs[14,20]. However, our endoscopic center was able to cope with the situation and no specific modification of endoscopic activities was required. In fact, 50% of endoscopic procedures were carried out in an operating room in Italy[14], whereas all endoscopic procedures at our hospital were performed in an endoscopy room, with the exception of one patient who required ventilator care in an intensive care unit due to GIB.

Endoscopy is recognized as an aerosol producing procedure as it causes coughing, retching, and splashing of gastric and fecal fluids. Due to physical proximity with patients, endoscopists are highly susceptible to saliva, nasal secretions, and aerosol droplets[14,20], and thus, endoscopic procedures can be a nidus of viral transmission to HCPs or patients[13,21]. In view of the risk of SARS-COV-2 transmission during endoscopic procedures, we placed focus on the protection of HCPs and timely treatment[2,7-9]. In the present study, the number of endoscopic procedures fell by ≥ 50% during the COVID-19 outbreak as compared with equivalent periods in 2018 and 2019, which concurs with a French report[22] and demonstrates that the COVID-19 pandemic had a huge impact[15]. There are several explanations for the remarkable reductions observed in endoscopic activities. First, we canceled or postponed most routine endoscopic procedures such as regular check-ups and routine follow-up visits after endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic mucosal resection, and polypectomy, and preoperative evaluations. Unlike the situations in Europe or the United States, where governments issued instructions to cancel or postpone routine endoscopy at times of lockdown, no specific directions regarding canceling or postponing endoscopy were issued by the metropolitan task-force committee[20,22,23]. Some endoscopies were canceled or postponed by patients because they were concerned about in-hospital infection, and this raised concerns that potential malignancies might be missed. In particular, for patients referred from clinics or medium-volume hospitals, delays of several months presented a risk of failure to diagnose occult malignancies and deterioration in cases of biopsy-confirmed early cancer. All things considered, we decided to resume endoscopy as soon as the pandemic was under control, because gastric and biliary cancer are endemic in Korea, and thus, delayed endoscopic evaluations posed the risk of a large clinical burden[20]. Second, consultations with endoscopic in-patient cases regarding preoperational evaluations or anemia work-ups were much reduced because most major surgeries were canceled. In addition, non-urgent endoscopies among in-patients were minimized to reduce the risk of in-hospital infection, and patient discharge was encouraged. Third, the task-force committee strongly advised physically vulnerable patients, especially elderly and immunocompromised patients, to refrain from visiting tertiary hospitals if possible, because the COVID-19 fatality rate among this population was reported to be 28% to 62%[24].

Of the 336 emergency endoscopes conducted during the three years studied, 65 were carried out during the COVID-19 outbreak. Regardless of endoscopy type, numbers of endoscopic procedures performed in 2020 plummeted by around 50% as compared with previous years, which concurs with European reports[14]. Many factors may have contributed to this phenomenon. First, patients were reluctant to visit ERs of tertiary hospitals because of the perceived risk of COVID-19 exposure, despite the stringent measures taken to isolate and quarantine SARS-CoV-2 confirmed patients. Similarly, in a previous study, the authors concluded that fear of leaving home and lockdown probably reduced ER visits[25]. Second, Koreans tend to prefer visiting the ERs of tertiary hospitals, rather than those of medium-volume hospitals, because of perceived medical competence, easy accessibility, and lower medical costs, irrespective of the type of emergency. However, during the COVID-19 outbreak, all ER visitors were processed intensively at a screening clinic for COVID-19 infection, which deterred patients with non-urgent conditions from visiting the ER, and probably played a key role in lowering the number of ER visitors. Third, fewer referrals from medium-volume hospitals and clinics also reduced the number of emergency endoscopies[25].

Our analysis of emergency endoscopies, excluding ERCP cases, showed that GIB was the most common indication. Unsurprisingly, the number of emergency endoscopies dropped by 43% in 2020 and the number of bleeding-related lesions fell by 10%-45% as compared with 2018/2019. We suggest these results were due to; (1) A lockdown or ban of social gatherings, which reduced excessive alcohol consumption. A notable change in lifestyle may have reduced the numbers of variceal bleeding and vomiting-related Mallory-Weiss bleeding cases; (2) The stay-at-home-policy by the government appeared to encouraged elderly, cardiocerebrovascular, and immunocompromised patients to take their medications (e.g., proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers, and mucosal protectants) regularly. This was somewhat expected as COVID-19 outbreaks are associated with remarkable reductions in ulcer-related GIB cases[22]; (3) Marked reductions in numbers of invasive procedures, including colon polypectomy, gastric or colon endoscopic submucosal dissection, or endoscopic mucosal resection may have substantially decreased the incidence of GIB, which concurs with the findings of a previous study[22]. Actually, during the COVID-19 outbreak, most non-urgent, invasive endoscopic procedures were postponed; and (4) Reduced outdoor activities may have lowered trauma-associated incidences of sprains, contusions, and fractures, which are indirectly associated with lower rates of ulcer-related GIBs due to reduced consumption of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and over-the-counter painkillers.

Telemedicine offers an alternative in the COVID-19 era because non-contact systems reduce unnecessary hospital visits and the risk of in-hospital infection[26,27]. In addition, telemedicine reduces time spent traveling, lowers the medical fees and reduces the physicians’ workloads, though it also requires capital investment for the installation of equipment. Nevertheless, telemedicine might be suitable for carefully selected patients. Unfortunately, it has not been approved in Korea due to legal issues.

It is noteworthy that mean hemoglobin level was significantly lower during the COVID-10 period than during 2018 or 2019[28-30], which we presumed was caused by patients with suspicious or overt GIB delaying ER visits as much as possible due to the lockdown or fear of in-hospital infection. Furthermore, the number of patients that underwent endoscopy in 2020 was lower than in previous years, but the percentage that required endoscopic intervention was higher, which also suggests that on average more severely affected patients visited the ER during the COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, it has been reported that since the onset of COVID-19, more than 20% of HCPs in Italy have been infected[20]. In contrast, as of November, 2020, no case of endoscopy-related SARS-CoV-2 infection has been reported in a patient or members of medical staff at our endoscopic center.

This study has a number of limitations. First, it was conducted retrospectively at a single center in a tertiary hospital and involved a relatively small number of cases. Moreover, due to its retrospective nature, emergency endoscopy criteria were not strictly defined. Second, endoscopies were mainly performed based on ER physicians’ rather than endoscopist’s requests, and some non-urgent cases may have been included. Third, we did not collect follow-up data on postponed or rescheduled elective endoscopies. Fourth, the sizes and causes of benign ulcers, the presence of Helicobacter pylori, and the outcomes of suspicious small bowel bleeding were not fully investigated.

Summarizing, the impact of COVID-19 was substantial and resulted in dramatic reductions in endoscopic procedures and changes in patient behaviors. The explosive increase in the number of COVID-19 patients encountered in Daegu (South Korea) resulted in endoscopy being viewed as hazardous to HCPs and patients. Here, we describe how we stopped viral spread, quarantined COVID-19 patients, and adapted to the new endoscopic environment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first East Asian report to be issued on the impacts of COVID-19 on emergent endoscopic activities and outcomes. Long-term follow-up studies are required to determine the effects of COVID-19 induced changes in patient behaviors, endoscopy types, missed malignancies and disease progressions, and patient outcomes.

Surges of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients have markedly influenced the treatment policies of tertiary hospitals because of the need to protect medical staff and contain viral transmission, but the impact of COVID-19 on emergency gastrointestinal endoscopies has not been determined.

Endoscopy involves direct contact with patients’ body fluid, oropharyngeal mucosa and fecal fluid. Furthermore, endoscopic procedures can act as covert vehicles of transmission due to aerosol formation during endoscopic manipulations, and it is known that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 can survive in the gastrointestinal tract for more than 2 wk.

This study was undertaken to compare endoscopic activities and analyze the clinical outcomes of emergency endoscopies performed before and during the COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu City, the epicenter of the first serious outbreak in South Korea.

The medical records of patients that underwent endoscopy from February 18 to March 28, 2020, at a tertiary teaching hospital were retrospectively evaluated. Demographic data, laboratory data, chief complaints, types of endoscopies, causes of emergent endoscopies, and endoscopic reports were reviewed during the above-mentioned period and for the same periods during 2018 and 2019.

The number of emergent endoscopic procedures performed in 2020 was 48.8% and 54.8% lower than in 2018 and 2019, respectively. During the COVID-19 outbreak, the main indications for endoscopy were melena (36.7%), hematemesis (30.6%), and hematochezia (10.2%), and gastrointestinal bleeding was the most common endoscopic abnormalities detected (39 cases in 2018, 51 in 2019, and 35 in 2020).

The COVID-19 outbreak resulted in significant reductions in endoscopic procedures and changes in patient behaviors.

Long-term follow-up studies are required to determine the effects of COVID-19 induced changes in patient behaviors, endoscopy types, missed malignancies, disease progressions, and patient outcomes.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Atoum M, Mohammadi M S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239-1242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11409] [Cited by in RCA: 11507] [Article Influence: 2301.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Konturek PC, Harsch IA, Neurath MF, Zopf Y. COVID-19 - more than respiratory disease: a gastroenterologist's perspective. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2020;71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chiu PWY, Ng SC, Inoue H, Reddy DN, Ling Hu E, Cho JY, Ho LK, Hewett DG, Chiu HM, Rerknimitr R, Wang HP, Ho SH, Seo DW, Goh KL, Tajiri H, Kitano S, Chan FKL. Practice of endoscopy during COVID-19 pandemic: position statements of the Asian Pacific Society for Digestive Endoscopy (APSDE-COVID statements). Gut. 2020;69:991-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 49.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gralnek IM, Hassan C, Beilenhoff U, Antonelli G, Ebigbo A, Pellisè M, Arvanitakis M, Bhandari P, Bisschops R, Van Hooft JE, Kaminski MF, Triantafyllou K, Webster G, Pohl H, Dunkley I, Fehrke B, Gazic M, Gjergek T, Maasen S, Waagenes W, de Pater M, Ponchon T, Siersema PD, Messmann H, Dinis-Ribeiro M. ESGE and ESGENA Position Statement on gastrointestinal endoscopy and the COVID-19 pandemic. Endoscopy. 2020;52:483-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Irisawa A, Furuta T, Matsumoto T, Kawai T, Inaba T, Kanno A, Katanuma A, Kawahara Y, Matsuda K, Mizukami K, Otsuka T, Yasuda I, Tanaka S, Fujimoto K, Fukuda S, Iishi H, Igarashi Y, Inui K, Ueki T, Ogata H, Kato M, Shiotani A, Higuchi K, Fujita N, Murakami K, Yamamoto H, Ito T, Okazaki K, Kitagawa Y, Mine T, Tajiri H, Inoue H. Gastrointestinal endoscopy in the era of the acute pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019: Recommendations by Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (Issued on April 9th, 2020). Dig Endosc. 2020;32:648-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sultan S, Lim JK, Altayar O, Davitkov P, Feuerstein JD, Siddique SM, Falck-Ytter Y, El-Serag HB; AGA Institute. AGA Rapid Recommendations for Gastrointestinal Procedures During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 739-758. e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 55.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Soetikno R, Teoh AYB, Kaltenbach T, Lau JYW, Asokkumar R, Cabral-Prodigalidad P, Shergill A. Considerations in performing endoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:176-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang J, Wang S, Xue Y. Fecal specimen diagnosis 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020;92:680-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 60.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li LY, Wu W, Chen S, Gu JW, Li XL, Song HJ, Du F, Wang G, Zhong CQ, Wang XY, Chen Y, Shah R, Yang HM, Cai Q. Digestive system involvement of novel coronavirus infection: Prevention and control infection from a gastroenterology perspective. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kwon YS, Park SH, Kim HJ, Lee JY, Hyun MR, Kim HA, Park JS. Screening Clinic for Coronavirus Disease 2019 to Prevent Intrahospital Spread in Daegu, Korea: a Single-Center Report. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim SW, Lee KS, Kim K, Lee JJ, Kim JY; Daegu Medical Association. A Brief Telephone Severity Scoring System and Therapeutic Living Centers Solved Acute Hospital-Bed Shortage during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Daegu, Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Musa S. Hepatic and gastrointestinal involvement in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): What do we know till now? Arab J Gastroenterol. 2020;21:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Perisetti A, Gajendran M, Boregowda U, Bansal P, Goyal H. COVID-19 and gastrointestinal endoscopies: Current insights and emergent strategies. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:715-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lauro A, Pagano N, Impellizzeri G, Cervellera M, Tonini V. Emergency Endoscopy During the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in the North of Italy: Experience from St. Orsola University Hospital-Bologna. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:1559-1561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mahadev S, Aroniadis OS, Barraza L, Agarunov E, Goodman AJ, Benias PC, Buscaglia JM, Gross SA, Kasmin FE, Cohen JJ, Carr-Locke DL, Greenwald DA, Mendelsohn RB, Sethi A, Gonda TA; NYSGE research committee. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on endoscopy practice: results of a cross-sectional survey from the New York metropolitan area. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:788-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Repici A, Maselli R, Colombo M, Gabbiadini R, Spadaccini M, Anderloni A, Carrara S, Fugazza A, Di Leo M, Galtieri PA, Pellegatta G, Ferrara EC, Azzolini E, Lagioia M. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of endoscopy should know. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:192-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 76.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Castro Filho EC, Castro R, Fernandes FF, Pereira G, Perazzo H. Gastrointestinal endoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic: an updated review of guidelines and statements from international and national societies. Gastrointest Endosc 2020; 92: 440-445. e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | ASGE Quality Assurance in Endoscopy Committee; Calderwood AH, Day LW, Muthusamy VR, Collins J, Hambrick RD 3rd, Brock AS, Guda NM, Buscaglia JM, Petersen BT, Buttar NS, Khanna LG, Kushnir VM, Repaka A, Villa NA, Eisen GM. ASGE guideline for infection control during GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1167-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Kim SB, Kim KH. The proposed algorithm for emergency endoscopy during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. Korean J Intern Med. 2020;35:1027-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Repici A, Pace F, Gabbiadini R, Colombo M, Hassan C, Dinelli M; ITALIAN GI-COVID19 Working Group. Endoscopy Units and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak: A Multicenter Experience From Italy. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 363-366. e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rahman MR, Perisetti A, Coman R, Bansal P, Chhabra R, Goyal H. Duodenoscope-Associated Infections: Update on an Emerging Problem. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:1409-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Becq A, Jais B, Fron C, Rotkopf H, Perrod G, Rudler M, Thabut D, Hedjoudje A, Palazzo M, Amiot A, Sobhani I, Dray X, Camus M; Parisian On-call Endoscopy Team (POET). Drastic decrease of urgent endoscopies outside regular working hours during the Covid-19 pandemic in the paris area. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44:579-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Blackett JW, Kumta NA, Dixon RE, David Y, Nagula S, DiMaio CJ, Greenwald D, Sharaiha RZ, Sampath K, Carr-Locke D, Guerson-Gil A, Ho S, Lebwohl B, Garcia-Carrasquillo R, Rajan A, Annadurai V, Gonda TA, Freedberg DE, Mahadev S. Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Undergoing Endoscopy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multicenter Study from New York City. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Weiss P, Murdoch DR. Clinical course and mortality risk of severe COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1014-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 94.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | O'Grady J, Leyden J, MacMathuna P, Stewart S, Kelleher TB. ERCP and SARS-COV-2: an urgent procedure that should be immune. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:976-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Montemurro N. Intracranial hemorrhage and COVID-19, but please do not forget "old diseases" and elective surgery. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;92:207-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Montemurro N, Perrini P. Will COVID-19 change neurosurgical clinical practice? Br J Neurosurg. 2020;1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Markar SR, Clarke J, Kinross J; PanSurg Collaborative group. Practice patterns of diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in England. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:804-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | D'Ovidio V, Lucidi C, Bruno G, Miglioresi L, Lisi D, Bazuro ME. A snapshot of urgent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy care during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:1839-1840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kim J, Doyle JB, Blackett JW, May B, Hur C, Lebwohl B; HIRE study group. Effect of the Coronavirus 2019 Pandemic on Outcomes for Patients Admitted With Gastrointestinal Bleeding in New York City. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 1155-1157. e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |