Published online May 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3212

Peer-review started: December 31, 2020

First decision: January 25, 2021

Revised: February 3, 2021

Accepted: March 12, 2021

Article in press: March 12, 2021

Published online: May 6, 2021

Processing time: 112 Days and 5.9 Hours

Endodermal sinus tumors (ESTs), which arise primarily in children and adolescents, account for 20% of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors, but constitute only 1% of all ovarian malignancies. Treatment of ESTs consists of surgical staging with fertility-sparing surgery and chemotherapy.

A 15-year-old nulliparous patient was diagnosed with disseminated ovarian ESTs after laparoscopic unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy using uncontained power morcellation for treatment of a ruptured solid adnexal mass in another hospital. Exploratory laparotomy; total abdominal hysterectomy, right salpingo-oophorectomy, and lymphadenectomy were performed with optimal debulking, and surgical stage 3C was assigned to the patient.

In 2014, the Food and Drug Administration noted that power morcellation was probably associated with a risk of disseminating suspected cancerous tissue. Furthermore, the use of power morcellation to remove solid adnexal mass is considered a contraindication because of the potential for a malignant tumor. This case report aims to warn of the dangers of using uncontained power morcellation to treat solid adnexal masses.

Core Tip: Laparoscopic power morcellation is useful technique in that large specimens can be removed through a small incision. However, the use of power morcellation to remove solid adnexal masses is considered a contraindication because solid adnexal masses cannot be completely excluded from the possibility of malignant tumor. Here, we report a case of disseminated ovarian endodermal sinus tumors after laparoscopic unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy using uncontained power morcellation. This case highlights the possibility of disseminated suspected malignancy after laparoscopic uncontained power morcellation, and gynecologists should be cautious about using uncontained power morcellation for solid adnexal masses.

- Citation: Oh HK, Park SN, Kim BR. Laparoscopic uncontained power morcellation-induced dissemination of ovarian endodermal sinus tumors: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(13): 3212-3218

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i13/3212.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3212

Endodermal sinus tumors (ESTs) of the ovary, also known as yolk sac tumors because they are derived from the primitive yolk sac, are the second most common malignant ovarian germ cell tumor (MOGCT) after dysgerminoma and account for 20% of MOGCTs and 1% of all ovarian malignancies. They are rare and highly malignant tumors that occur mainly in children and adolescents and are characterized by a large solid and cystic tumor[1]. Abdominal pain is the most common symptom experienced in 77% of patients, and an abdominal or pelvic mass is palpated in 74% of patients[2]. Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels increase in most ESTs and can be used as an indicator to monitor the disease progress and the patient response to treatment[3]. With the development of various combination chemotherapy regimens, the long-term survival of patients has improved, and many MOGCT patients have been able to undergo fertility-sparing surgery. Indeed, long-term survival has become common for almost all patients with early-stage tumors and most patients with advanced-stage tumors[4].

As various instruments have been developed to maximize the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, laparoscopic techniques are now widely used in the field of gynecological surgery. In particular, laparoscopic power morcellation is commonly used when performing laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy or myomectomy, as the ability to remove large specimens through a small incision is highly advantageous[5]. In rare cases, it is also used in the removal of benign-appearing adnexal masses[6]. However, the use of power morcellation to remove solid adnexal masses is considered a contraindication because solid adnexal masses cannot be completely excluded from the possibility of being a malignant tumor (such as dysgerminoma, EST, Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor, etc.), even if the preoperative examination showed a high probability of benignity or a frozen biopsy performed during surgery is benign[7,8].

Here, we report a case of disseminated ovarian ESTs throughout the entire peritoneal cavity after laparoscopic unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy using uncontained power morcellation.

A 15-year-old nulliparous patient was transferred to our hospital for complaints of a dull, aching abdominal pain and abdominal distension that lasted 1 wk.

About 4 wk prior, the patient had undergone an emergency exploratory laparoscopy at another hospital that transferred her to our hospital. It was documented in her medical record that another hospital revealed hemoperitoneum due to continuous bleeding from a ruptured left solid ovarian mass during surgery and performed laparoscopic unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy using uncontained power morcel

The patient had a free previous medical history.

The personal and family histories were unremarkable.

Upon admission, she looked pale, but her vital signs were stable (blood pressure 110/60 mmHg, pulse rate 80 beats/min, body temperature 36.9 °C, oxygen saturation 99% on room air). Physical examination revealed lower abdominal tenderness and abdominal distension with a palpated abdominal mass, approximately 15 cm in size. There was no guarding or rigidity.

Laboratory test results showed a normal complete blood count except mild anemia with a serum hemoglobin level of 10.7 g/dL and hematocrit of 31.4%. In addition, we found normal electrolytes, blood urea, creatinine, and liver function. We ordered tumor marker tests, and the results were as follows: Serum AFP > 6000 ng/mL, lactate dehydrogenase (937 IU/L), human chorionic gonadotropin (1.54 mIU/mL), and cancer antigen 125 (174 U/mL).

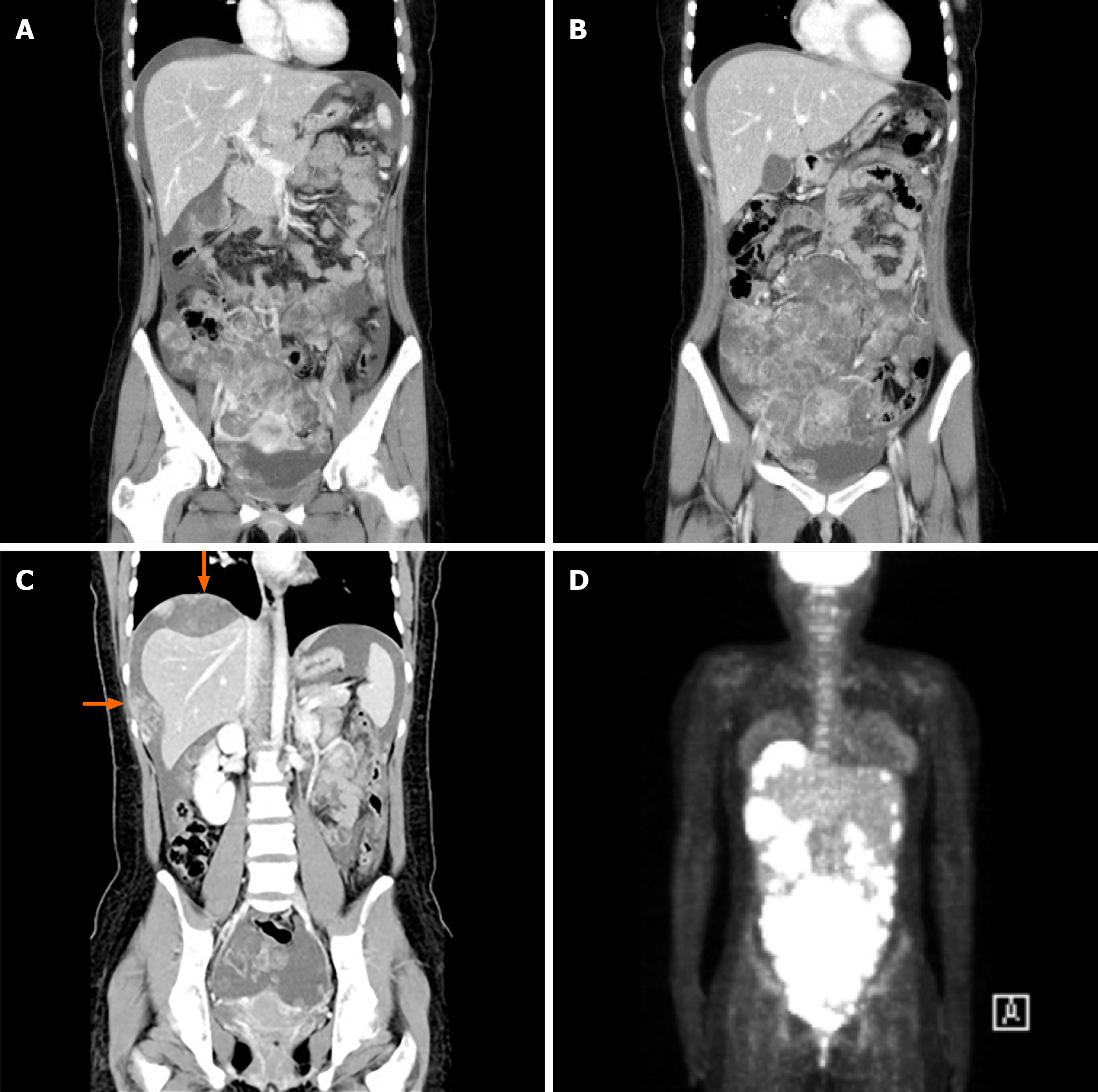

Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple metastases of malignancy in the uterus, right adnexa, omentum, mesentery, diaphragm, and peritoneal surfaces in the perihepatic space (Figure 1A-C). A large ascites was also reported. Positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) revealed multifocal hypermetabolism in the same region as the suspected metastasis on CT (Figure 1D). Chest radiography showed normal findings and no pleural effusion.

Elective exploratory laparotomy was performed after discussing treatment options with the patient and her family members. Intraoperatively, approximately 1 L of ascites was drained. A 16 cm × 12 cm omental cake adherent to an ovarian tumor (9 cm × 8 cm) arising from the right ovary invading the uterus was present. Other metastatic masses of 8 cm × 5 cm and 6 cm × 3 cm, each originating from the diaphragm and parietal peritoneum in perihepatic space, was found to compress the liver, not the parenchymal metastases. The left ovary and fallopian tube were not visible because of previous left salpingo-oophorectomy. Surgical stage 3C was assigned to the patient.

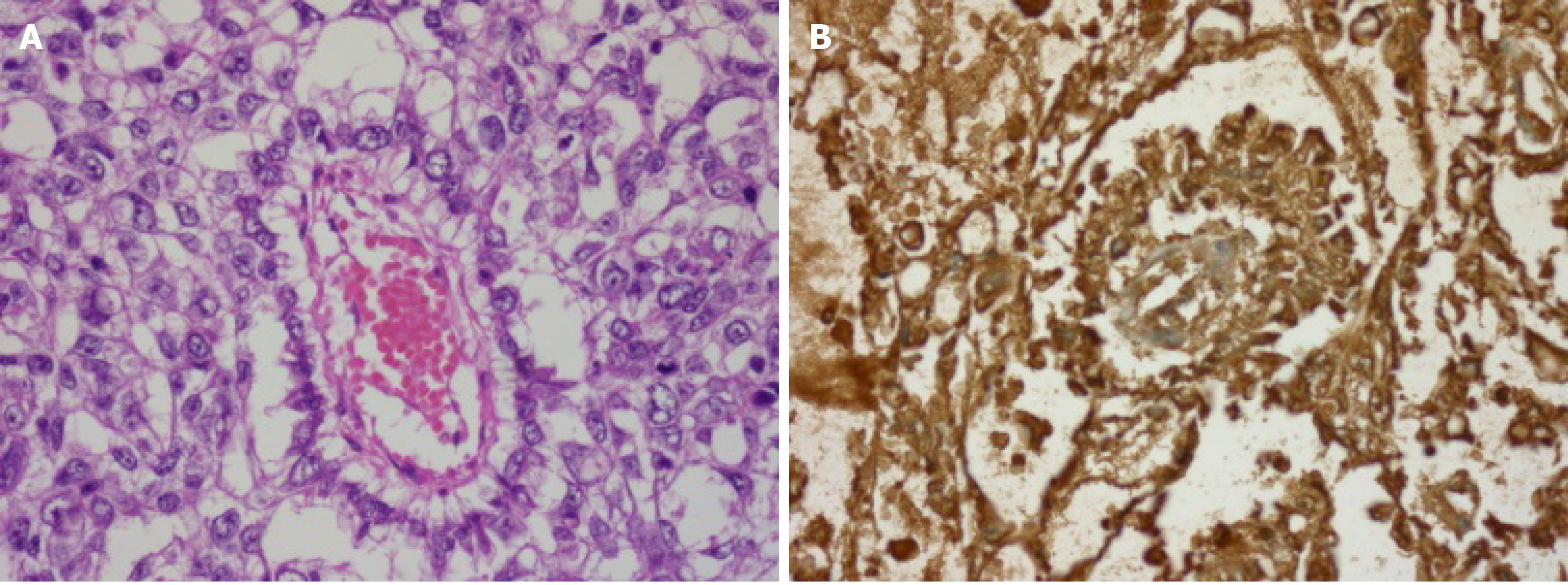

Histopathological examination of the resected specimen revealed a metastatic EST in all specimens except multiple lymph nodes (Figure 2).

Total abdominal hysterectomy, right salpingo-oophorectomy, and lymphadenectomy were performed with optimal debulking. She received transfusion of 8 units of red blood cells with 4 units of fresh frozen plasma intraoperatively for hemodynamic stabilization. Her postoperative course was uneventful, and she received adjuvant chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) regimen 3 wk after surgery.

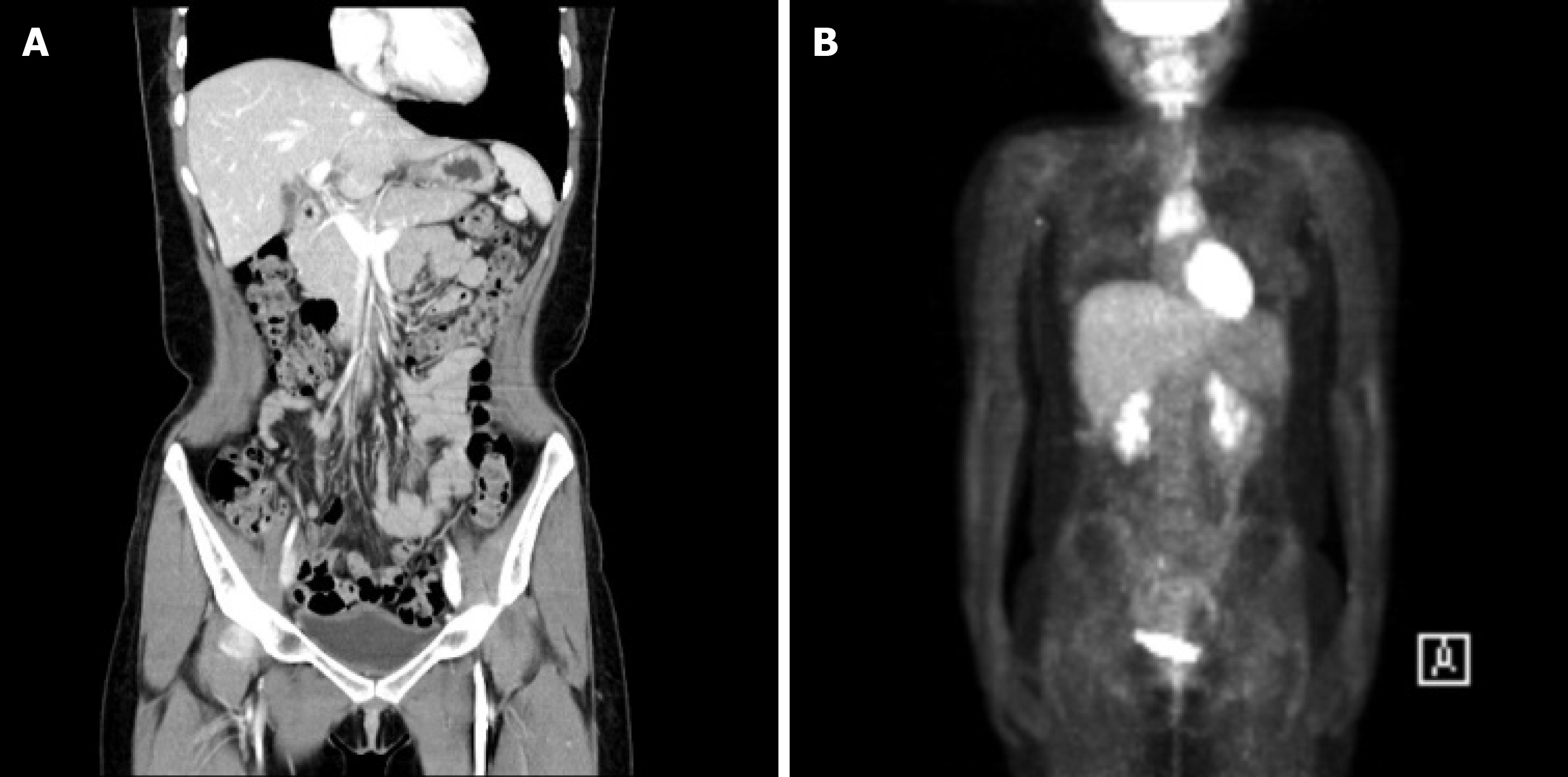

After completing chemotherapy cycles, her serum AFP level (1.36 ng/mL) was normalized. No recurrence was observed during the 6-year follow-up period with serum AFP, abdominal CT, and PET-CT (Figure 3). She is currently receiving hormonal therapy.

Several complications related to power morcellation, such as ectopic leiomyoma (leiomyomatosis), endometriosis or ovarian remnant syndrome, dissemination of occult malignancy, and direct visceral injury (such as bladder, bowel, and ureteral injuries), have been reported to date. These are responsible for reducing the patient’s long-term survival[9]. For this reason, the Food and Drug Administration safety communication in 2014 announced a review showing concerns about laparoscopic power morcellation used in hysterectomy or myomectomy[10]. In detail, two contraindications are recommended. First, laparoscopic power morcellators are contraindicated in the removal of uterine tissue containing presumed benign fibroids in patients who are in the peri- or post-menopausal period or are candidates for en bloc tissue removal through the vagina or mini-laparotomy incision. Second, use of laparoscopic power morcellators is contraindicated in the gynecologic field to morcellate tissue that is known or suspected to contain malignancy. Since this announcement, various studies have been conducted to provide safer alternatives, such as a tissue containment system[5]. Recently, in February 2020, laparoscopic power morcellation for hysterectomy or myomectomy with only a tissue containment system was recommended for appropriate patient groups[11]. However, current data on the use of a tissue containment systems are still limited and more research is needed[12].

Scribner et al[6] reported a case of managing a large, benign-appearing adnexal mass by single-site laparoscopy using a power morcellator and argued that it was a case showing the feasibility and potential safety of their technique. However, Canis et al[7] reported a case in which a 12 cm, mainly solid ovarian mass was treated by laparoscopy. The patient underwent unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy via laparoscopy, and the ovarian mass was diagnosed as a teratoma in a frozen biopsy obtained during surgery. The mass was morcellated and removed through a 4 cm abdominal incision. An immature teratoma was diagnosed on a permanent section, and 3 wk later, a stage 4 peritoneal gliosis containing mature and immature implants was observed. The patient received chemotherapy, total hysterectomy with contralateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and debulking surgery. Based on this case, the authors stated that intraperitoneal morcellation should be considered a contraindication in the treatment of ovarian masses.

Surgical staging was not performed at the time of surgery in another hospital, but our patient could be estimated as surgical stage 1C because ruptured unilateral ovarian EST and non-existent pelvic extension (normal-appearing contralateral ovary and intraperitoneal organs in macroscopically) were identified. The patient was referred to our hospital 4 wk after surgery, and exploratory laparotomy was performed, and the patient was diagnosed with metastatic stage 3C EST. To our knowledge, there have been no cases in which metastatic stage 3C EST has been diagnosed by spreading into the peritoneal cavity within a short period after laparoscopic unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for the treatment of stage 1C EST.

EST occurs mostly in children or adolescent periods and responds well to platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy. Therefore, in the case of early-stage MOGCTs including EST, the initial surgery performed is fertility-sparing surgery (unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). Various methods of fertility-sparing cytoreductive surgery are performed according to the need for fertility preservation, bilateral involvement of the ovary, and the chemotherapy-sensitive nature in the case of advanced-stage tumors[4]. After consulting with the patient and family members, total abdominal hysterectomy, contralateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and lymphadenectomy with optimal debulking were determined. Postoperatively, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy (BEP regimen) and continued to be disease-free for 6 years. Unfortunately, the patient is undergoing hormonal replacement therapy because of the surgical menopause condition and is experiencing a loss of fertility. We regret not performing fertility-sparing cytoreductive surgery instead of hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Metastatic dissemination caused by morcellation of solid adnexal masses is extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of laparo

Metastatic dissemination caused by morcellation of solid adnexal masses is extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of laparoscopic uncontained power morcellation-induced dissemination of ovarian EST. This case highlights the possibility of disseminated suspected malignancy after laparoscopic uncontained power morcellation as a method of solid adnexal mass extraction, and gynecologists should be cautious about using uncontained power morcellation for solid adnexal masses.

We would like to thank the Wonkwang University.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Beirne JP S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Dällenbach P, Bonnefoi H, Pelte MF, Vlastos G. Yolk sac tumours of the ovary: an update. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:1063-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kurman RJ, Norris HJ. Endodermal sinus tumor of the ovary: a clinical and pathologic analysis of 71 cases. Cancer. 1976;38:2404-2419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Talerman A, Haije WG, Baggerman L. Serum alphafetoprotein (AFP) in diagnosis and management of endodermal sinus (yolk sac) tumor and mixed germ cell tumor of the ovary. Cancer. 1978;41:272-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li J, Wu X. Current Strategy for the Treatment of Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors: Role of Extensive Surgery. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Miller CE. Morcellation equipment: past, present, and future. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:69-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Scribner DR Jr, Lara-Torre E, Weiss PM. Single-site laparoscopic management of a large adnexal mass. JSLS. 2013;17:350-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Canis M, Pouly JL, Wattiez A, Mage G, Manhes H, Bruhat MA. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses suspicious at ultrasound. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:679-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Froyman W, Landolfo C, Amant F, Van den Bosch T, Vergote I, Coosemans A, Testa A, Valentin L, Bourne T, Calster BV, Timmerman D. Morcellation and risk of malignancy in presumed ovarian fibromas/fibrothecomas. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:273-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Noel NL, Isaacson KB. Morcellation complications: From direct trauma to inoculation. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;35:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | U S. Food and Drug Administration. UPDATED Laparoscopic Uterine Power Morcellation in Hysterectomy and Myomectomy: FDA Safety Communication. [cited 5 July 2020]. Silver Spring: U.S. Food and Drug Administration [Internet]. Available from: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170404182209/https:/www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm424443.htm. |

| 11. | U S. Food and Drug Administration. UPDATE: The FDA recommends performing contained morcellation in women when laparoscopic power morcellation is appropriate. [cited 5 July 2020]. Silver Spring: U.S. Food and Drug Administration [Internet]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/update-fda-recommends-performing-contained-morcellation-women-when-laparoscopic-power-morcellation. |

| 12. | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. FDA Releases New Guidance and Draft Product Labeling for Laparoscopic Power Morcellators. [cited 5 July 2020]. Washington: The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [Internet]. Available from: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/03/fda-guidance-draft-product-labeling-laparoscopic-power-morcellators. |