Published online May 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3095

Peer-review started: November 1, 2020

First decision: January 10, 2021

Revised: January 23, 2021

Accepted: February 22, 2021

Article in press: February 22, 2021

Published online: May 6, 2021

Processing time: 172 Days and 6.2 Hours

When autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) presents with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the possibility of spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) should be highly considered. In some cases, SCAD is considered an extrarenal manifestation of ADPKD depending on the pathological characteristics of the unstable arterial wall in ADPKD.

Here, we report a 46-year-old female patient with ADPKD who presented with ACS. Coronary angiography revealed no definite signs of dissection, while intravascular ultrasound revealed a proximal to distal dissection of the left circumflex. After a careful conservative medication treatment, the patient exhibited favorable prognosis.

In cases of ADPKD co-existing with ACS, differential diagnosis of SCAD should be considered. Moreover, when no clear dissection is found on coronary angiography, IVUS should be performed to prevent missed diagnosis.

Core Tip: We report an acute chest pain patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, the patient was ultimately diagnosed with spontaneous coronary artery dissection after a comprehensive intracoronary imaging. Therefore, coronary angiography and further intravascular imaging might be very essential for the diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease accompanied by spontaneous coronary artery dissection.

- Citation: Qian J, Lai Y, Kuang LJ, Chen F, Liu XB. Spontaneous coronary dissection should not be ignored in patients with chest pain in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(13): 3095-3101

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i13/3095.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3095

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is defined as an epicardial coronary artery dissection that is not related to atherosclerosis or trauma and is non-iatrogenic. Mechanistically, SCAD caused myocardial injury by triggering the formation of intramural hematoma (IMH) or intimal tear rather than the rupture of atherosclerotic plaque or thrombosis in the lumen arising from coronary artery obstruction[1]. SCAD manifests as unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction or even sudden cardiac death. Application of coronary angiography and intravascular imaging revealed that the prevalence of SCAD is higher than previously thought[2]. Recent studies have shown that SCAD may account for 1%-4% of all acute coronary syndrome (ACS) after excluding iatrogenic, traumatic, and atherosclerotic dissections, especially in young women[3,4]. SCAD is associated with relatively few traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and its underlying etiology include arterial disease, genetic disease or glucocorticoid therapy, especially hereditary or acquired arterial disease or systemic inflammatory disease, which are usually exacerbated by emotional stress[5-7].

The relationship between autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and SCAD remains unclear, with only few case reports so far[8-14]. A retrospective study showed that among 66360 SCAD patients, 60 (0.09%) had ADPKD[15]. Different from previous reports, we report a case of SCAD co-existing with ACS without obvious dissection in angiographic analysis, which was identified by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). We highlight the necessity of IVUS in the diagnosis of SCAD in patients with ADPKD presenting as chest pain and no visible dissection on coronary angiography.

A 46-year-old woman with a family history of ADPKD presented to our emergency department with acute chest pain.

Her chest pain lasted for 1 day and radiated to the back of her left shoulder.

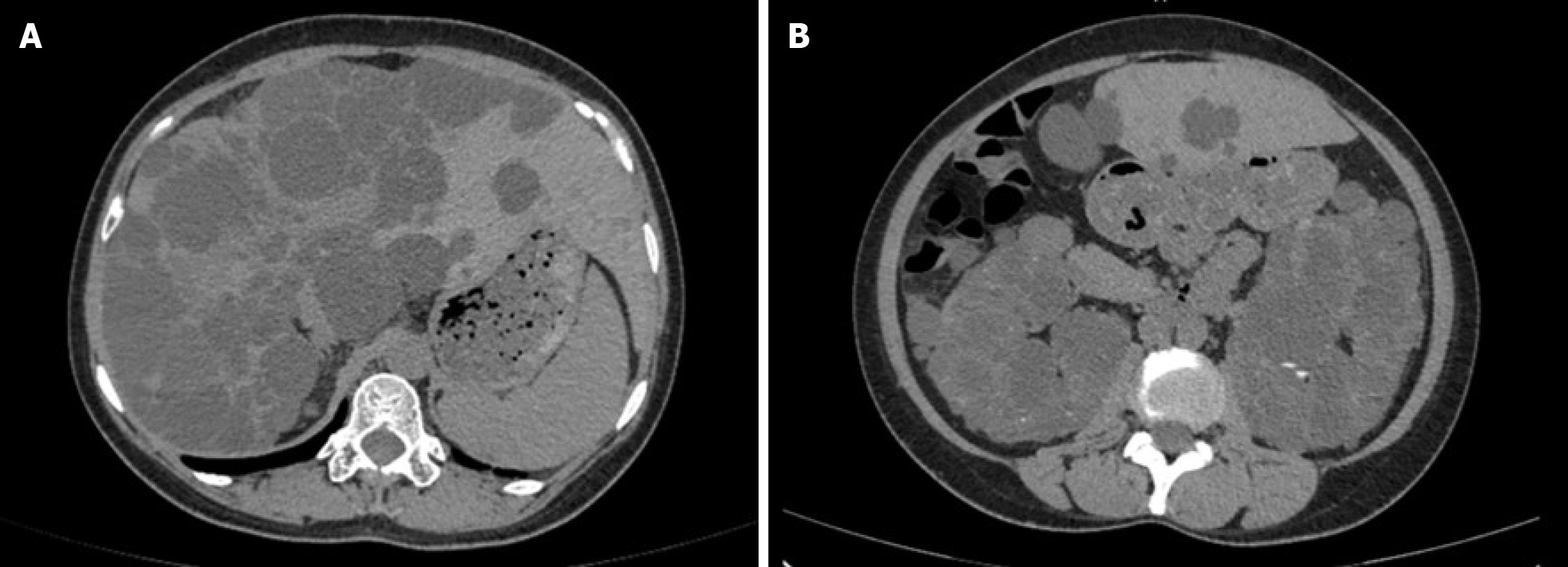

Her ADPKD had affected kidney function (eGFR: 15.98 mL/min/1.73 m2), and she exhibited extrarenal features of polycystic liver as shown in Figure 1.

She had no cardiovascular risk factors except a long history of hypertension and emotional stress. Blood pressure at admission was 142/70 mmHg.

Auscultation revealed that the heart sounds were normal, without rales in the lungs.

At the emergency department, her troponin I was 0.268 ng/mL and the peak value during hospitalization was 1.928 ng/mL. Hematological examination found no signs of inflammation and anemia. The low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was 3.32 mmol/L, High density lipoprotein cholesterol cholesterol was 1.10 mmol/L, total cholesterol was 4.07 mmol/L, triglyceride was 0.82 mmol/L, and body mass index was 21.87 kg/m2.

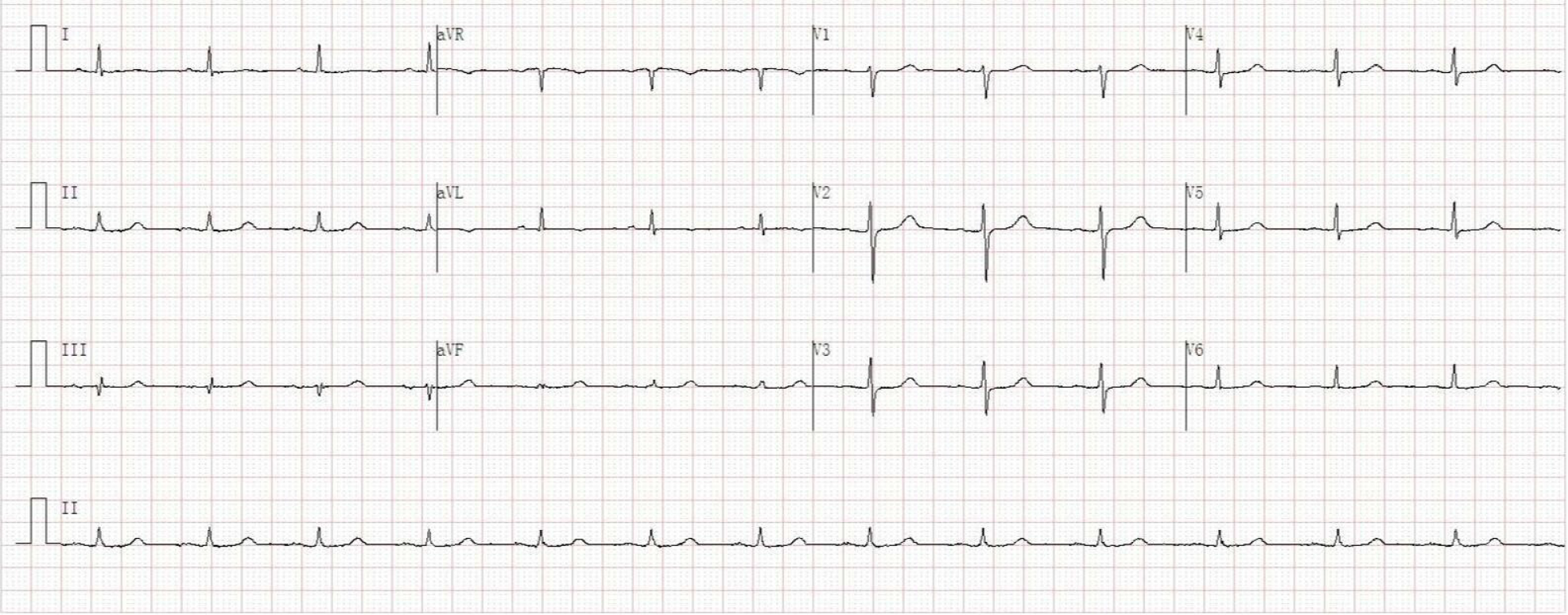

Her initial electrocardiogram in the emergency room was normal without any changes in ST segment and T wave (Figure 2). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed mild dilation of the left atrium (left atrium inner diameter 42 mm), normal left ventricular ejection fraction (62%), and mild mitral regurgitation.

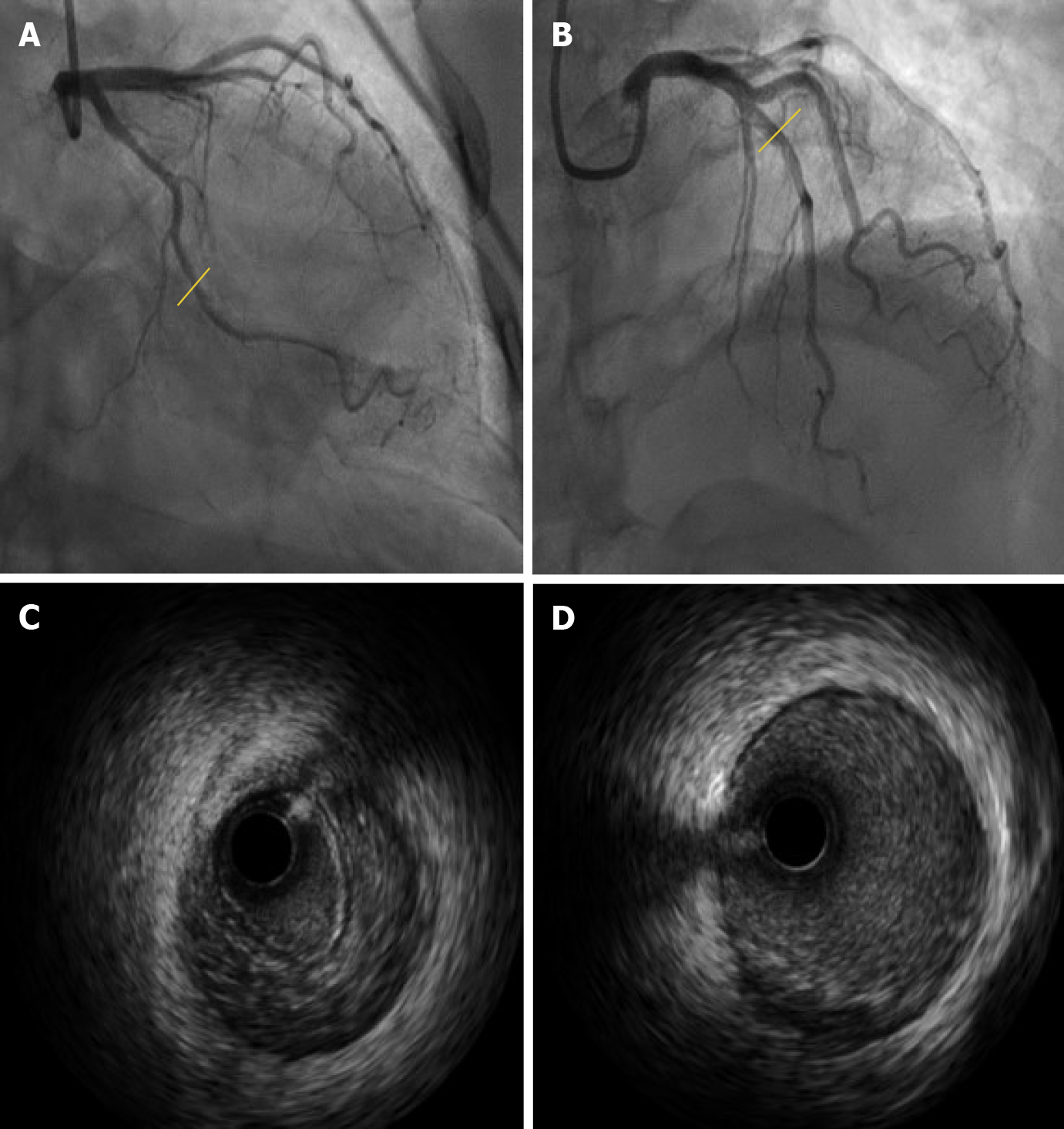

After three days of antiplatelet therapy, we performed coronary angiography which found no obvious characteristics of coronary dissection (Figure 3A and B). Given the particularity of the patient, IVUS examination was performed at the same time to further examine the condition of her coronary artery. Interestingly, obvious IMH formation from the distal to proximal was found in the left circumflex (Figure 3C). IVUS was also performed on the left anterior descending artery, and found only a few atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 3D).

The final diagnosis of the presented case is spontaneous coronary artery dissection.

The patient was admitted to the coronary care unit and was given monotherapy antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel 75 mg every day. In the following days, the patient was in stable condition and discharged from the hospital.

After three months of clopidogrel treatment and nearly a year of follow-up, the patient remained stable with no symptoms such as chest pain recurred.

We report a case of a young female patient with SCAD combined with ADPKD, with no clear dissection in the coronary angiography but obvious signs of dissection in IVUS. The patient had a long history of ADPKD, and she visited emergency department because of sudden chest pain. However, the coronary angiography did not find clear signs of stenosis or dissection, so it was very important to perform IVUS to identify the luminal conditions. At that time, vital signs of the patient were stable and there were no other life-threatening comorbidities, so IVUS examination was relatively safe and necessary. Previous studies have shown that the incidence of SCAD is higher than expected, especially in young female patients[3,4]. ADPKD is the most common hereditary kidney disease. It is mainly caused by mutations in PKD1 and -2 genes encoding polycystin 1 and 2, respectively, which plays an important role in the development and maintenance of the vascular system[16]. Its extrarenal manifestations include liver cysts, intracranial aneurysms and heart valve disease. However, cases in which, SCAD co-exists with ADPKD are rare, with only a few cases reported so far. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a normal coronary angiography but IVUS diagnosis of dissection in ADPKD patients. Prior cardiovascular genetic studies found that only 1 in 73 SCAD patients had ADPKD[17]. However, given the unstable arterial wall in ADPKD, it should be considered as a high-risk population of SCAD[16,18].

SCAD patients often have fewer traditional cardiovascular risk factors. It is currently believed that SCAD is affected by many factors, such as inherited or acquired arterial disease, underlying arterial disease, genes, glucocorticoid, systemic inflammation, environment and emotional stress[1]. Coronary angiography is important in the diagnosis of SCAD. When the structure of the arterial tube wall is unclear, intravascular imaging modalities such as IVUS or optical coherence tomography (OCT) should be considered. The typical signs of SCAD on coronary angiography include multiple radiolucent cavities and extraluminal contrast agent retention, suggesting that there may be spiral dissection or intraluminal filling defect. Saw SCAD coronary angiography is classified as follows: Type 1 refers to the typical signs of multiple radiolucent cavities or tube wall filling with contrast agent; type 2 refers to multiple stenosis with different length and degree; type 2A refers to the cause normal diffuse arterial stenosis defined by the proximal and distal segments. Type 2B refers to diffuse stenosis extending to the distal end of the artery; and type 3 refers to focal or tubular stenosis, usually less than 20 mm in length, similar to athero-sclerosis[19].

For cases that are difficult or impossible to diagnose by angiography, like in the present case, intravascular imaging can be used as an auxiliary diagnostic method. Although the coronary angiography results of ADPKD patients might be normal, it is very necessary to perform IVUS to exclude SCAD in these patients, and IVUS should be performed as early as possible. IVUS can detect intimal tears, false lumen formation, IMH and intraluminal thrombosis, but its resolution cannot completely distinguish the above lesion features. The advantage of IVUS is that it has strong penetrating power and can evaluate the depth and range of IMH. OCT can clearly show the structure of the arterial wall, and is superior to IVUS in revealing the lumen-intima boundary, intimal tear, false lumen, IMH, and intraluminal thrombus. Thus, OCT makes the diagnosis of SCAD easy. In cases where angiography diagnosis is not possible, if intravascular imaging is safe, OCT can be considered. Intravascular imaging technology presents certain potential risks, such as expanding the scope of the dissection and occlusion of the true cavity. Therefore, before performing intravascular imaging, the benefits and risks must be weighed.

Currently, the treatment strategy of SCAD still remains controversies. Hence, conservative treatment strategies are widely used for patients with SCAD. In the current patient, we adopted conservative treatment strategy because we considered the patient as a low-risk patient. First, vital signs of the patient remained stable at the time of admission, except for chest pain. Secondly, chest pain symptoms were quickly relieved. After the IVUS operation was performed to confirm the dissection, the patient did not have chest pain and other symptoms, and no further abnormal conditions were indicated by ECG and echocardiography. Finally, the patient was well treated with conservative medication and had no symptoms such as chest pain. For high-risk patients such as those with persistent ischemia, left main stem dissection and hemodynamic instability, revascularization is preferred over medical treatment[3]. It is currently controversial concerning application of standard drugs in SCAD patients as for ACS. SCAD patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) should receive dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) as specified in the guidelines[1]. There is no clear evidence whether SCAD patients who did not undergo PCI should receive DAPT. In theory, the benefits of early DAPT for SCAD patients include prevention of thrombosis caused by intimal dissection. However, many physicians still avoid DAPT considering the increased risk of bleeding and there is currently no evidence of its benefit. Based on the above considerations, we administrated antiplatelet monotherapy with clopidogrel in our patient and achieved good prognosis.

SCAD should be considered during differential diagnosis of ADPKD patients with acute chest pain. Coronary angiography is an important method for confirming the diagnosis of ADPKD. It is very important perform IVUS or OCT when coronary angiography is uncertainty.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yasuji I S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, Adlam D, Arslanian-Engoren C, Economy KE, Ganesh SK, Gulati R, Lindsay ME, Mieres JH, Naderi S, Shah S, Thaler DE, Tweet MS, Wood MJ; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; and Stroke Council. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Current State of the Science: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e523-e557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 647] [Cited by in RCA: 818] [Article Influence: 116.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tweet MS, Gulati R, Aase LA, Hayes SN. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a disease-specific, social networking community-initiated study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:845-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Adlam D, Alfonso F, Maas A, Vrints C; Writing Committee. European Society of Cardiology, acute cardiovascular care association, SCAD study group: a position paper on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3353-3368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 65.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nishiguchi T, Tanaka A, Ozaki Y, Taruya A, Fukuda S, Taguchi H, Iwaguro T, Ueno S, Okumoto Y, Akasaka T. Prevalence of spontaneous coronary artery dissection in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5:263-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lettieri C, Zavalloni D, Rossini R, Morici N, Ettori F, Leonzi O, Latib A, Ferlini M, Trabattoni D, Colombo P, Galli M, Tarantini G, Napodano M, Piccaluga E, Passamonti E, Sganzerla P, Ielasi A, Coccato M, Martinoni A, Musumeci G, Zanini R, Castiglioni B. Management and Long-Term Prognosis of Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:66-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saw J, Aymong E, Sedlak T, Buller CE, Starovoytov A, Ricci D, Robinson S, Vuurmans T, Gao M, Humphries K, Mancini GB. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: association with predisposing arteriopathies and precipitating stressors and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:645-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rashid HN, Wong DT, Wijesekera H, Gutman SJ, Shanmugam VB, Gulati R, Malaipan Y, Meredith IT, Psaltis PJ. Incidence and characterisation of spontaneous coronary artery dissection as a cause of acute coronary syndrome--A single-centre Australian experience. Int J Cardiol. 2016;202:336-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Verlaeckt E, Van de Bruaene L, Coeman M, Gevaert S. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a patient with hereditary polycystic kidney disease and a recent liver transplant: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2019;3:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Grover P, Fitzgibbons TP. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Afari ME, Quddus A, Bhattarai M, John AR, Broderick RJ. Spontaneous coronary dissection in polycystic kidney disease. R I Med J. 2013;96:44-45. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Klingenberg-Salachova F, Limburg S, Boereboom F. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in polycystic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5:44-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee CC, Fang CY, Huang CC, Ng SH, Yip HK, Ko SF. Computed tomography angiographic demonstration of an unexpected left main coronary artery dissection in a patient with polycystic kidney disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2011;26:W4-W6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Itty CT, Farshid A, Talaulikar G. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a woman with polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:518-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Basile C, Lucarelli K, Langialonga T. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: One more extrarenal manifestation of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease? J Nephrol. 2009;22:414-416. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Krittanawong C, Kumar A, Johnson KW, Luo Y, Yue B, Wang Z, Bhatt DL. Conditions and Factors Associated With Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (from a National Population-Based Cohort Study). Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:249-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cornec-Le Gall E, Alam A, Perrone RD. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2019;393:919-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 65.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kaadan MI, MacDonald C, Ponzini F, Duran J, Newell K, Pitler L, Lin A, Weinberg I, Wood MJ, Lindsay ME. Prospective Cardiovascular Genetics Evaluation in Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e001933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Neves JB, Rodrigues FB, Lopes JA. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and coronary artery dissection or aneurysm: a systematic review. Ren Fail. 2016;38:493-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Saw J, Mancini GB, Humphries K, Fung A, Boone R, Starovoytov A, Aymong E. Angiographic appearance of spontaneous coronary artery dissection with intramural hematoma proven on intracoronary imaging. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;87:E54-E61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |