Published online May 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3090

Peer-review started: October 15, 2020

First decision: January 24, 2021

Revised: January 28, 2021

Accepted: February 26, 2021

Article in press: February 26, 2021

Published online: May 6, 2021

Processing time: 187 Days and 7.8 Hours

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa (DEB-Pr) is a rare subtype of DEB, characterized by recurrent pruritus of the extremities, pruritus papules, nodules, and mossy-like plaques. To date, fewer than 100 cases have been reported. We report a misdiagnosed 30-year-old man with sporadic late-onset DEB-Pr who responded well to tacrolimus treatment, thereby serving as a guide to correct diagnosis and treatment.

A 30-year-old man presented with recurrent itching plaques of 1-year duration in the left tibia that aggravated and involved both legs and the back. Examination revealed multiple symmetrical, purple, and hyperpigmented papules and nodules with surface exfoliation involving the tibia and dorsum of the neck with negative Nissl's sign, no abnormalities in the skin, mucosa, hair, or fingernail, and no local lymph node enlargement. Blisters were never reported prior to presentation. Serum immunoglobulin E level was 636 IU/mL. Clinical manifestations suggested DEB-Pr. Histological examination showed subepidermal fissure, scar tissue, and milia. Direct immunofluorescence showed no obvious abnormalities. However, we were unable to perform electron microscopy or genetic research following his choice. We treated him with topical tacrolimus. After 2 wk, the itching alleviated, and the skin lesions began to subside. No adverse reactions were observed during treatment.

Topical tacrolimus is a safe treatment option for patients with DEB-Pr and can achieve continuous relief of severe itching.

Core Tip: At present, fewer than 100 cases of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa (DEB-Pr) have been reported. Delayed cases coupled with diversity of skin lesions make the diagnosis difficult. We report a late-onset case in which the patient did not develop the disease until the age of 30 years. There were no associated skin lesions in children and adulthood, and no family history was reported. The case was misdiagnosed many times, suggesting the importance of skin histopathology in diagnosing DEB-Pr. This patient was successfully treated with tacrolimus.

- Citation: Wang Z, Lin Y, Duan XW, Hang HY, Zhang X, Li LL. Misdiagnosed dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(13): 3090-3094

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i13/3090.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3090

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa (DEB-Pr) is a rare type of DEB. The combination of intense itching and skin fragility leads to skin hypertrophy, lichenified plaques, pruritic papules, plaques, and nodules secondary to scratching[1]. The lesions may be located on the calves and thighs, forearms, elbows, the dorsum of the hand, shoulders, and lower back, especially in the extensor surfaces of the limbs. Most patients have similar skin lesions when young; however, they are not uncommon in adulthood. This subtype was first described by McGrath et al[2] in 1994. Like all other forms of DEB, its molecular pathology involves a genetic mutation that encodes for anchored fibrin type VII collagen (COL7A1). The inheritance of DEB-Pr may be dominant, invisible, or caused by sporadic genetic mutations. Here, we present the case of a patient without a family history who developed the disease in adulthood and responded well to topical tacrolimus. This case could suggest a basis for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

A 30-year-old Chinese man presented to the outpatient clinic of our hospital over one year with multiple intermittent itching plaques on both calves and the back.

The symptoms began in January 2018 with a rash on the anterior portion of the tibia of his left leg with substantial itching. This gradually spread to the anterior tibia and back within 6 mo. This was misdiagnosed as prurigo nodularis and lichen planus in many hospitals; however, histopathological examination was not performed. Consequently, treatment involved topical steroids (Mometasone Furoate Cream) and oral antihistamines (Loratadine Tablets) for a long time. Unfortunately, satisfactory results were not achieved.

The patient denied any history of other diseases and allergies.

No relevant information on smoking, drinking, and genetic history was reported.

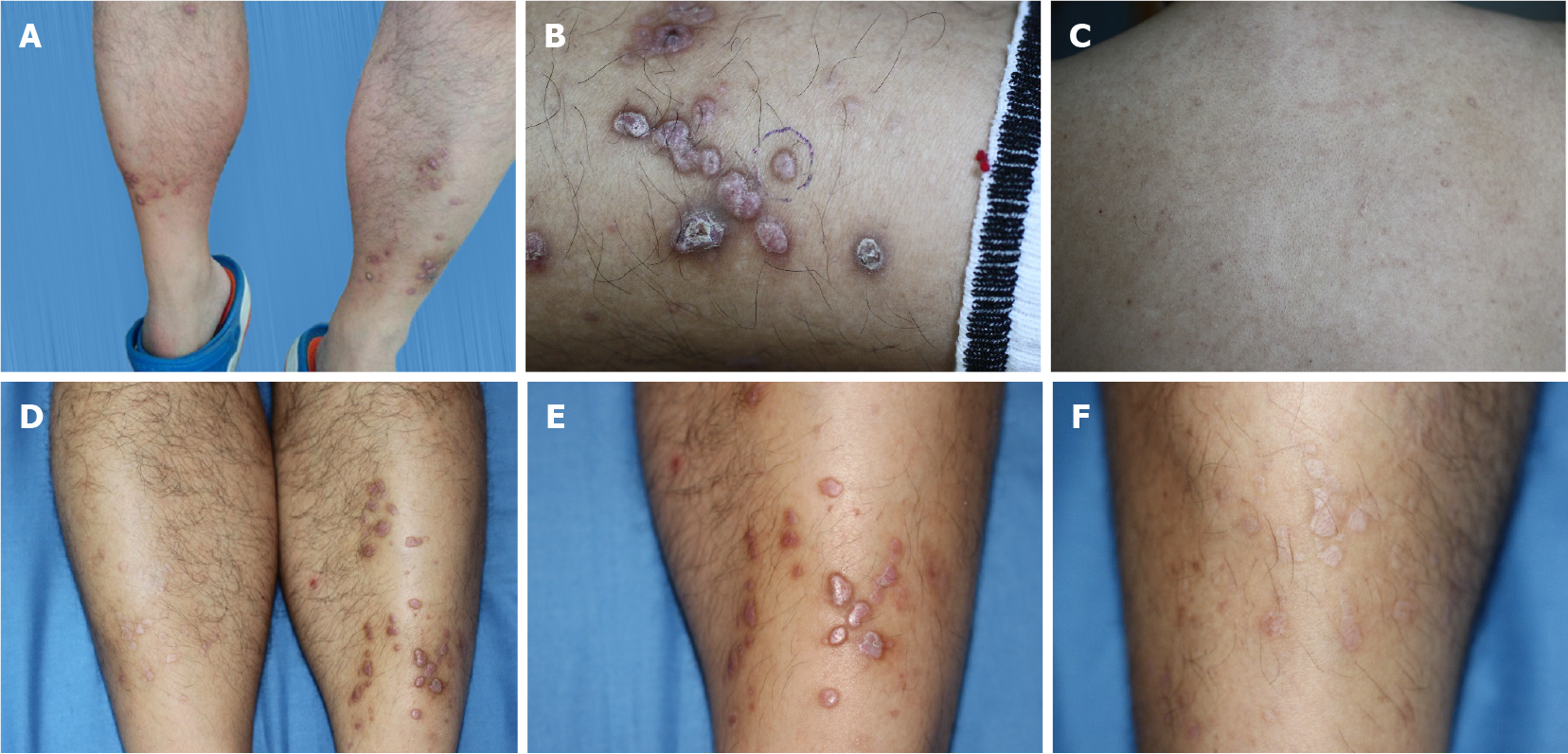

Physical examination revealed multiple symmetric, violet, and hyperpigmented papules and nodules involving both shins and nape of the neck with surface excoriations (Figure 1A-C). Nikolsky’s sign was negative. Other parts of the skin, mucosa, hair, and nails revealed no abnormalities and no regional lymphadenopathy.

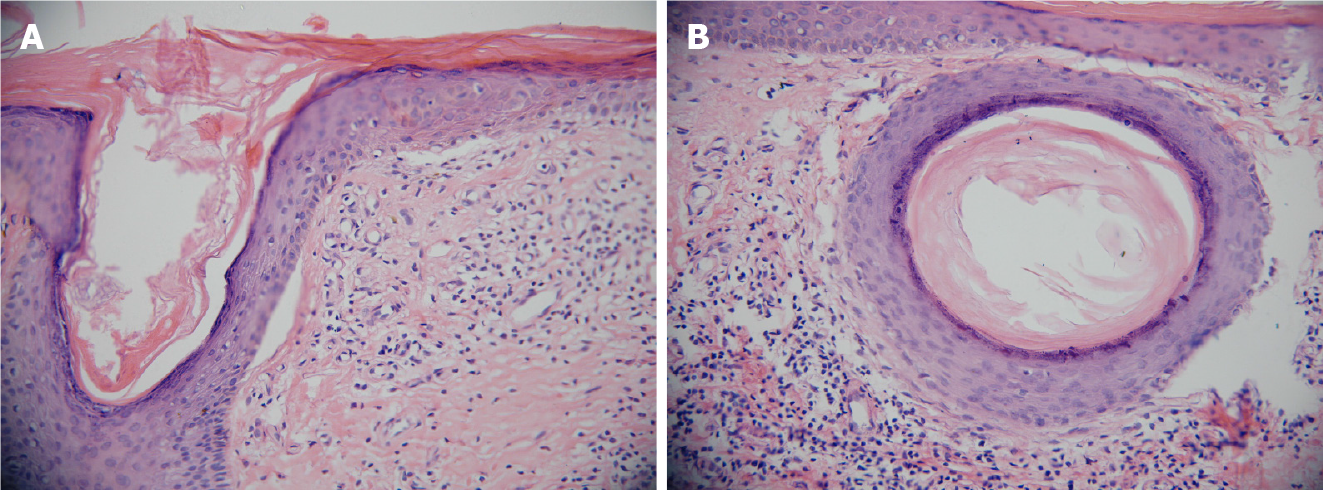

Routine laboratory tests, including serum biochemistry, were within normal limits. However, the level of serum immunoglobulin E was elevated at 636 IU/mL. Histological examination revealed subepidermal fissure and formation of scar tissue and milia (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) revealed immunoglobulin (Ig) G (-), IgA (-), IgM (-), C1q (-), and C3a (-). Electron microscopy and mutation analysis were not carried out as decided by the patient.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was DEB-pr.

Therapy was initiated with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment administered to the lower extremity and back twice daily.

After 2 wk, the itching and scratching decreased, the progression of mossy plaque and purple scar stopped, and some of the lesions began to disappear. One month later, the lesions improved by 50% (Figure 1D-F). There were no side effects after continuous treatment for 1 mo. On follow-up till date, no recurrence has occurred.

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a hereditary mechanical bullous dermatosis characterized by the formation of blisters caused by skin fragility and mechanical trauma. DEB is one of the four main subtypes of EB, caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, which encodes type VII collagen. DEB-Pr is a rare clinical subtype of DEB. In addition to the fragile skin and propensity to blister formation and ulceration after friction or trauma in DEB, DEB-Pr often appears as flat or macular papules in the anterior portion of the tibia, characterized by extreme itching. Therefore, it is easily misdiagnosed as prurigo or lichen planus. DEB-Pr usually begins to appear in childhood, with mild limb blisters and erosion. However, in some cases (as in our patient), clinical features appear later, in the second or third decade of life. In adulthood, patients may experience intense itching and skin manifestations such as multiple nodules and invasive lesions, skin fragility, scarring, and milia[3]. Therefore, adult patients are easily misdiagnosed with other diseases.

The following differential diagnoses should be ruled out before diagnosing DEB-Pr: Lichen simplex chronicus, hypertrophic lichen planus, lichen amyloidosis, prurigo nodularis, dermatitis artefacta, and pemphigoid nodularis. The clinical manifestations of DEB-Pr and pretibial dominant DEB overlap. However, the former includes severe itching and more extensive lesions[4]. Moreover, the age at onset of skin lesions in DEB-Pr is variable, and complete blisters tend not to form. Pemphigoid nodularis is one of the rarer variants of bullous pemphigoid (BP) and is characterized by overlapping clinical features of both prurigo nodularis and BP. The histological and immunological features of pemphigoid nodularis are those of classic BP, including epidermal hyperkeratosis. Linear deposition of IgG and IgM along the dermoepidermal junction is manifested in BP, but not in DEB-Pr via DIF testing. Thus, histopathology and DIF findings could exclude these two conditions.

The genetic model of DEB-Pr is not fixed. Most cases have autosomal dominant inheritance, although autosomal invisible inheritance and sporadic inheritance can also occur. Our patient had no family history, so we can consider the possibility of spontaneous gene mutation or invisible inheritance.

The age at first onset of DEB-Pr varies greatly, and it is not uncommon for skin lesions to occur before entering adulthood (as in our case). The cause of this delay has not been determined, and the case in this report also occurred after the age of 30. This raises a new problem: The challenge to the accurate diagnosis of delayed onset of DEB-Pr.

There are no established treatment modalities for DEB-Pr. Pruritus caused by various factors has potential clinical significance; therefore, treatment is aimed at relieving itching, stopping the progression of skin lesions, and preventing mechanical trauma and infection. Systemic antihistamines and topical steroids are usually taken for treatment, though the effect is often poor. Recent studies have described the efficacy of naltrexone[3], cyclosporine (Cys)[5], thalidomide[6], and dupilumab[7] for DEB-Pr. However, genetic counseling and therapy remain the most promising methods. Intractable pruritus is the main complaint in patients with DEB-Pr. Scratches caused by extreme itching lead to new lesions, thereby creating a vicious circle. Owing to repeated misdiagnoses, the skin of our patient became thinner due to the long-term use of steroids, which further aggravated skin fragility. Therefore, we need to find a drug that can treat itching without the side effects of topical corticosteroids. Tacrolimus is a stronger macrolide immunosuppressive drug than Cys. It was reported that the mechanisms of relieving itching in atopic eczema and other diseases include: Inhibition of the release of cytokines, skin mast cells, and eosinophil mediators[8-10]. Therefore, topical tacrolimus ointment is an alternative therapy for DEB-Pr. We treated our patient with topical tacrolimus ointment to control skin damage and relieve itching over a short period of time. After the diagnosis, the patient received skin care guidance while taking medication, stopped scratching, and improved the skin care routine. During treatment, his skin lesions continued to improve, although the treatment was not long-term. Nevertheless, to date, there has been no recurrence.

We report a typical sporadic adult case of DEB-Pr that was initially difficult to diagnose and misdiagnosed many times. Nodular pruritus and lichen planus were the main skin lesions. Skin biopsy, immunopathological examination, and mutational analysis are of great significance to correctly diagnose these cases, which are initially difficult to diagnose clinically. Following diagnosis, we observed the efficacy of topical tacrolimus. Therefore, we believe that tacrolimus can be used as a safe and effective treatment option to treat itching without aggravating skin fragility, thereby achieving continuous relief in these patients. It would also provide a treatment option for similar skin diseases characterized by intractable itching and skin fragility.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jeong KY S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Kim WB, Alavi A, Walsh S, Kim S, Pope E. Epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa: a systematic review exploring genotype-phenotype correlation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:81-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McGrath JA, Schofield OM, Eady RA. Epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa: dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa with distinctive clinicopathological features. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:617-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pallesen KAU, Lindahl KH, Bygum A. Dominant Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Pruriginosa Responding to Naltrexone Treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1195-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ee HL, Liu L, Goh CL, McGrath JA. Clinical and molecular dilemmas in the diagnosis of familial epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:S77-S81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Takahashi T, Mizutani Y, Ito M, Nakano H, Sawamura D, Seishima M. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa successfully treated with immunosuppressants. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1391-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rani S, Gupta A, Bhardwaj M. Epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa: A rare entity which responded well to thalidomide. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e13035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shehadeh W, Sarig O, Bar J, Sprecher E, Samuelov L. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa-associated pruritus with dupilumab. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1495-1497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Banky JP, Sheridan AT, Storer EL, Marshman G. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa with topical tacrolimus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:794-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sakuma S, Higashi Y, Sato N, Sasakawa T, Sengoku T, Ohkubo Y, Amaya T, Goto T. Tacrolimus suppressed the production of cytokines involved in atopic dermatitis by direct stimulation of human PBMC system. (Comparison with steroids). Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1219-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ohtsuki M, Morimoto H, Nakagawa H. Tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of adult and pediatric atopic dermatitis: Review on safety and benefits. J Dermatol. 2018;45:936-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |