Published online May 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3038

Peer-review started: December 17, 2020

First decision: December 25, 2020

Revised: February 7, 2021

Accepted: March 10, 2021

Article in press: March 10, 2021

Published online: May 6, 2021

Processing time: 126 Days and 10.7 Hours

Gallstone pancreatitis is one of the most common causes of acute pancreatitis. Cholecystectomy remains the definitive treatment of choice to prevent recurrence. The rate of early cholecystectomies during index admission remains low due to perceived increased risk of complications.

To compare outcomes including length of stay, duration of surgery, biliary complications, conversion to open cholecystectomy, intra-operative, and post-operative complications between patients who undergo cholecystectomy during index admission as compared to those who undergo cholecystectomy thereafter.

Statistical Method: Pooled proportions were calculated using both Mantel-Haenszel method (fixed effects model) and DerSimonian Laird method (random effects model).

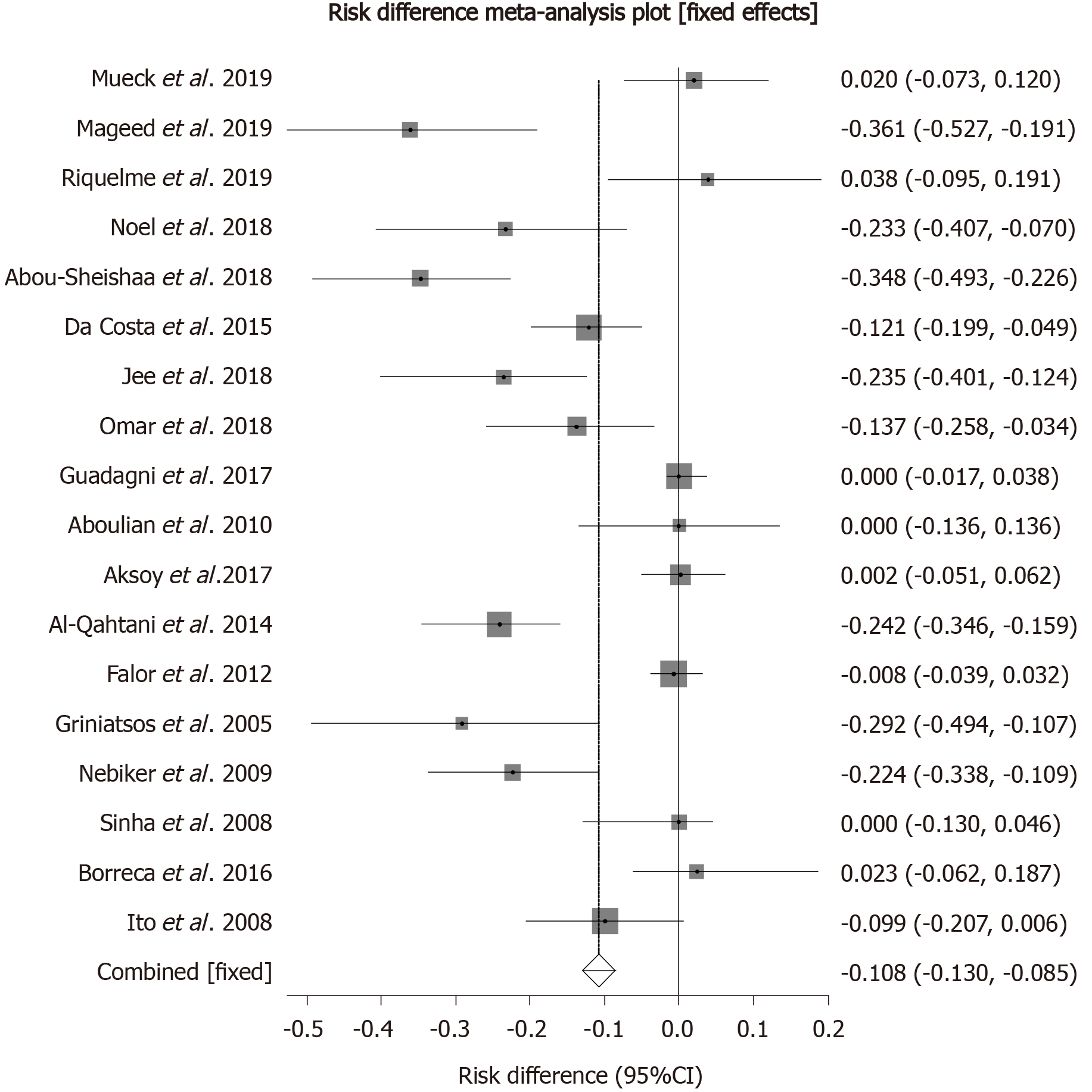

Initial search identified 163 reference articles, of which 45 were selected and reviewed. Eighteen studies (n = 2651) that met the inclusion criteria were included in this analysis. Median age of patients in the late group was 43.8 years while that in the early group was 43.6. Pooled analysis showed late laparoscopic cholecystectomy group was associated with an increased length of stay by 88.96 h (95%CI: 86.31 to 91.62) as compared to early cholecystectomy group. Pooled risk difference for biliary complications was higher by 10.76% (95%CI: 8.51 to 13.01) in the late cholecystectomy group as compared to the early cholecystectomy group. Pooled analysis showed no risk difference in intraoperative complications [risk difference: 0.41%, (95%CI: -1.58 to 0.75)], postoperative complications [risk difference: 0.60%, (95%CI: -2.21 to 1.00)], or conversion to open cholecystectomy [risk difference: 1.42%, (95%CI: -0.35 to 3.21)] between early and late cholecystectomy groups. Pooled analysis showed the duration of surgery to be prolonged by 39.11 min (95%CI: 37.44 to 40.77) in the late cholecystectomy group as compared to the early group.

In patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis early cholecystectomy leads to shorter hospital stay, shorter duration of surgery, while decreasing the risk of biliary complications. Rate of intraoperative, post-operative complications and chances of conversion to open cholecystectomy do not significantly differ whether cholecystectomy was performed early or late.

Core Tip: Despite recommendations from International societies rate of early cholecystectomy post gallstone pancreatitis remains low, presumably due to perceived increased risks of complications. Our updated meta-analysis shows early cholecystectomy leads to decreased risk of biliary complications in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis. It also leads to shorter hospital stay and shorter duration of surgery. Our data did not show any difference between the rate of intraoperative or postoperative complications between the two groups.

- Citation: Walayat S, Baig M, Puli SR. Early vs late cholecystectomy in mild gall stone pancreatitis: An updated meta-analysis and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(13): 3038-3047

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i13/3038.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3038

Acute pancreatitis remains as one of the most common reasons for emergency department visits. There were about 5210000 new cases of pancreatitis reported globally in 2016. This incidence rate represented almost a 30% increase in new cases as compared to 2006[1]. The rate of new cases is expected to continue to rise in the setting of obesity pandemic via increased gallstone formation and hypertriglyceridemia[1]. The common causes of pancreatitis include gallstones, alcohol, and iatrogenic pancreatitis. Alcohol and gallstones account for about 70%-80% of cases in the western world[2]. Among these two, gallstone pancreatitis is more common accounting for up to 50% of all cases[3]. Worldwide prevalence of gallstones is reported to be around 10%-20%, and presence of gallstones has been reported to be associated with 14-35 fold increase in risk of pancreatitis in males and 12-25 fold increase in risk of biliary pancreatitis in females[1].

Definitive treatment for gallstone pancreatitis remains laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The chances of recurrence without cholecystectomy have been reported to be as high as 30% along with increase in healthcare related costs[4]. The timing of cholecystectomy has remained an issue of significant importance and debate, while some groups advocate early surgery to decrease the risk of recurrence. Others however favor later surgery, citing concerns for increased risk of complications if surgery is done earlier due to acute inflammatory state present in early pancreatitis[2]. Most of the international societies currently recommend early cholecystectomy. The definition of early varies. The international society of pancreatology recommends cholecystectomy during index admission. American Gastroenterology society also recommends cholecystectomy during index admission[2]. Despite these recommendations the rate of cholecystectomy during index admission continues to remain on the lower side with only about 10% of patients reported to be receiving definitive treatment within the first 2 wk[5]. The trend for early cholecystectomy varies globally depending on the region, with the highest rate of early cholecystectomy being reported in Latin America, where almost 60% of patients presenting with biliary pancreatitis undergo cholecystectomy during index admission[6]. This was followed by North America and Europe where almost 43% and 52% patients underwent cholecystectomy during index admission while the lowest rate of cholecystectomy was reported in India where only 15% of patients underwent cholecystectomy during index admission[6].

The reason for this variability in rate of cholecystectomies while exactly unclear is likely multifactorial. The higher rate in Latin America was thought to be due to patients with biliary pancreatitis being admitted to surgery services primarily in that part of the world[6]. In India, the lower rate was thought to be due to patient preference and higher rate of transfers[6].

The most recent metanalysis by Zhong et al[7] included studies before March 2019, since then there have been 3 new randomized control trials that have been published that have not been included in the previous meta-analysis. In our meta-analysis we sought to include those new studies, as well as previous randomized control trials and retrospective studies to evaluate the efficacy of early vs late cholecystectomy for gallstone pancreatitis. In this study our aim is to compare outcomes including biliary complications, intra-operative complications, post-operative complications, rate of conversion to open cholecystectomy, length of stay and duration of surgery between early and late laparoscopic cholecystectomy groups.

We looked at studies assessing outcomes of early vs late cholecystectomy in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis. Early cholecystectomy was defined as cholecyste-ctomy occurring within 2 wk of onset of pancreatitis.

In our meta-analysis mild pancreatitis was defined by either Ransons score < 3[8], Atlanta classification[9] or computed tomography criteria[10]. We included studies that clearly defined mild gallstone pancreatitis using the above scoring systems, studies that clearly delineated early from late pancreatitis, and studies that clearly reported our outcomes of interest.

We excluded studies without a comparison arm, studies with patients < 18, pregnant patients, studies that included pancreatitis of other etiologies, case reports, posters, abstracts, expert reviews, articles that did not report our essential outcomes, articles published in languages other than English, and articles that included people with severe gallstone pancreatitis.

Our outcomes of interest included differences in biliary complications before surgery, intraoperative complications, and post-operative complications. Biliary complications included recurrent pancreatitis, acute cholecystitis, acute cholangitis, biliary colic, jaundice, and common bile duct injury. Intraoperative complications included bile duct injury, and intra-operative bleeding requiring blood transfusion. Post op complications included bile leak, post-op bleeding requiring transfusion, pancreatitis, pseudocyst, pneumonia, pre-eclampsia or other systemic complications[5]. We also looked at the rate of conversion to open cholecystectomy, and the difference in length of stay and duration of surgery between the two groups.

Articles were searched in MEDLINE, PubMed, Ovid journals, Embase, Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature, ACP Journal Club, DARE, MEDLINE Non-Indexed Citations, OVID Healthstar, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The search was performed for the years, January 1992 to December 2019. Only articles in English were included. Abstracts were manually searched in the major gastroenterology journals for the past 3 years. The search terms used were ‘cholecystectomy’, ‘pancreatitis’ ‘laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Two authors (SW and AB) independently searched and extracted the data into an abstract form. Any differences were resolved by mutual agreement. The agreement between reviewers for the collected data was quantified using Cohen’s κ[7]. The following information was extracted from the study: Authors, year of publication, place, study design, number of patients, age, gender, length of stay, duration of surgery, and complications between early and late groups.

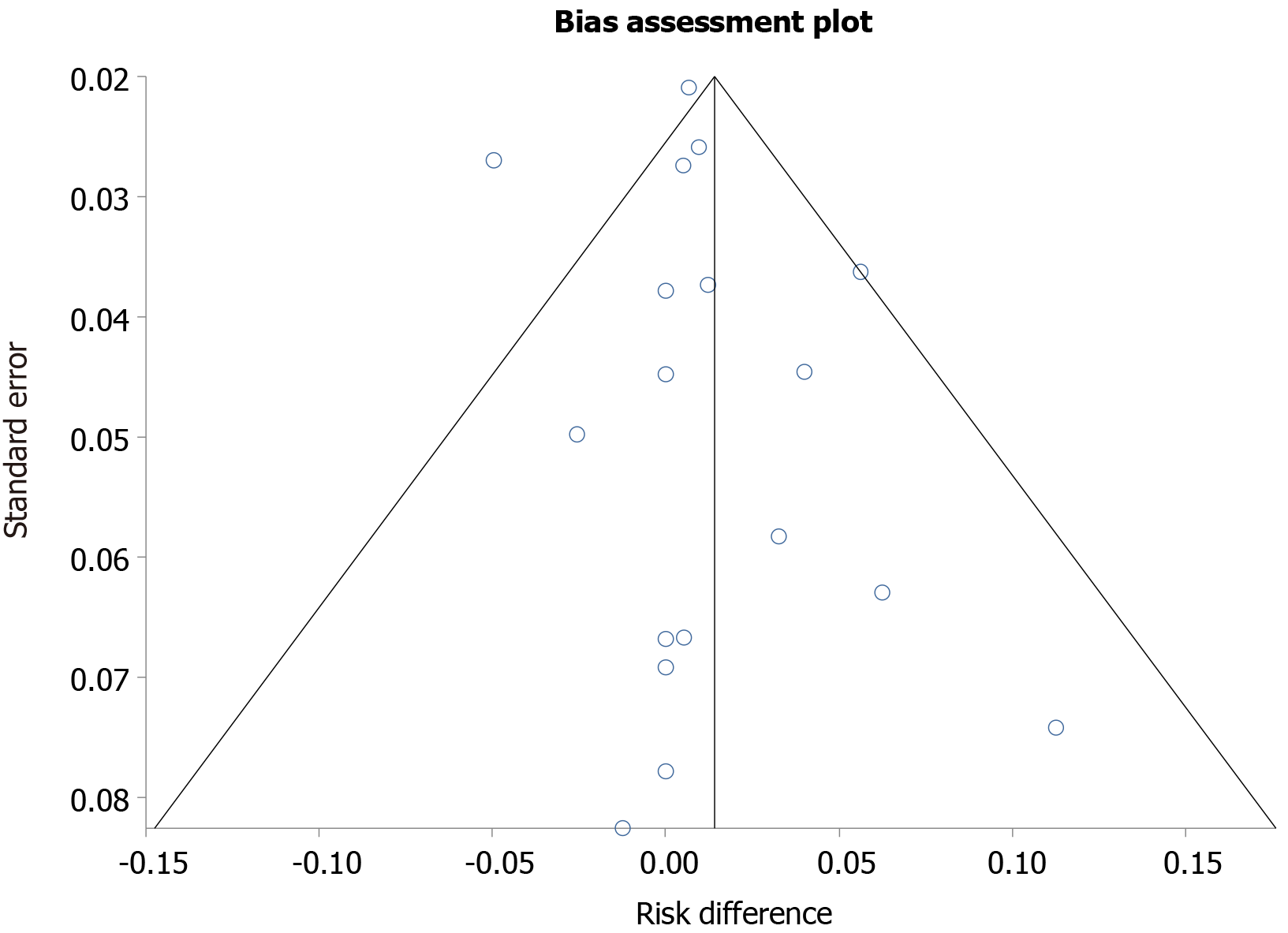

Microsoft excel was used for data collection and meta-analysis was performed using Stata version 14. Odds ratio was used to represent dichotomous outcomes with a 95%CI. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Random effect model was used for the meta-analysis in case of heterogeneity being statistically significant, otherwise fixed effects models were applied. Forest plots were drawn to show the point estimates in each study in relation to the summary pooled estimate. The width of the point estimates in the Forest plots indicates the assigned weight to that study. The heterogeneity among studies was tested using I2 statistic and Cochrane Q test based upon inverse variance weights[11]. I2 of 0% to 39% was considered as non-significant heterogeneity, 40% to 75% as moderate heterogeneity, and 76% to 100% as considerable heterogeneity. If P value is > 0.10, it rejects the null hypothesis that the studies are heterogeneous. The effect of publication and selection bias on the summary estimates was tested by both Harbord–Egger bias indicator and Begg–Mazumdar bias indicator[12,13]. Also, funnel plots were constructed to evaluate potential publication bias[14,15].

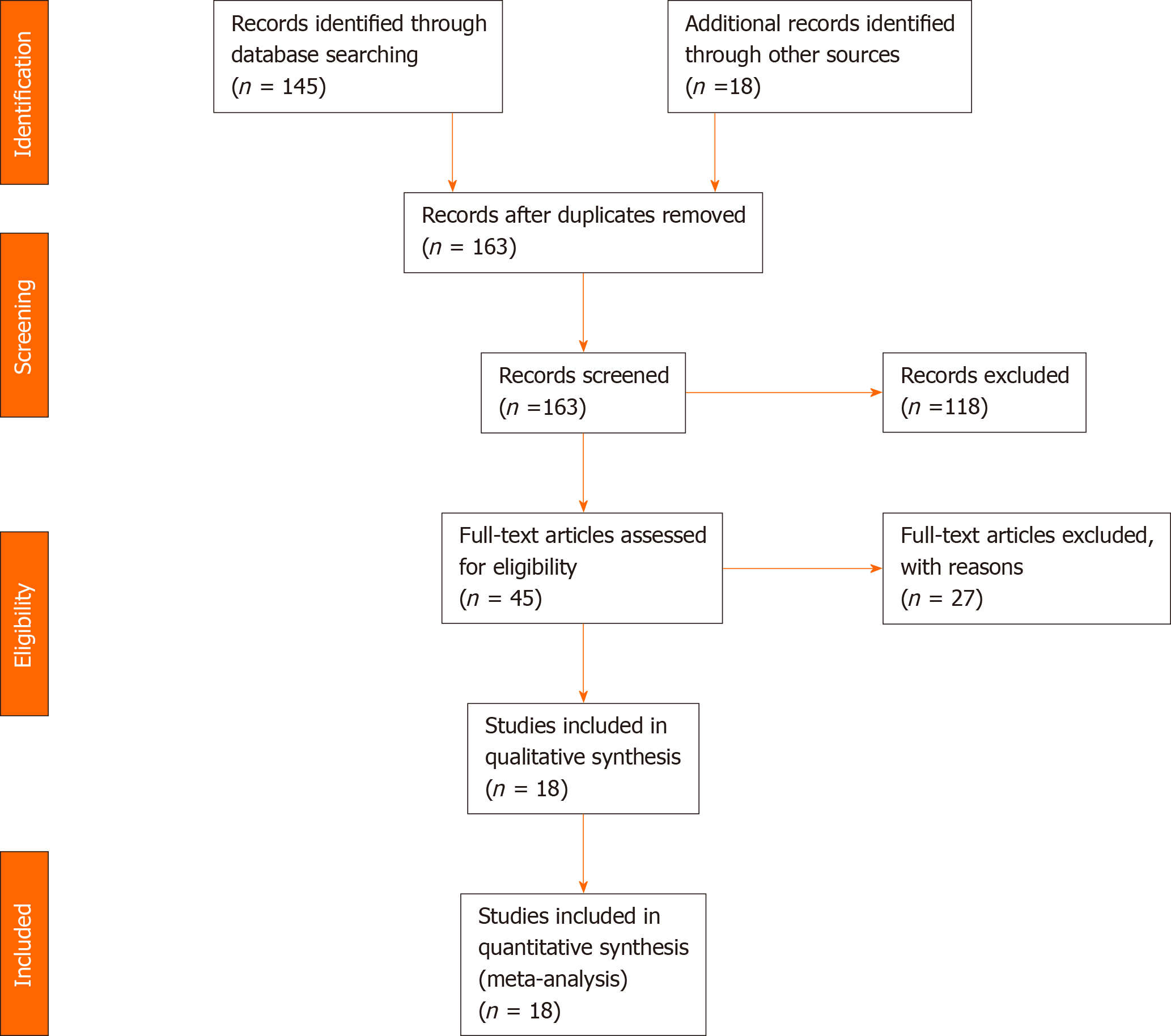

Initial search identified 163 reference articles based on our search criteria. After thorough screening, removal of abstracts, review papers and duplicates eighteen studies were selected and included in this analysis. Nine studies were randomized control trials, while others were retrospective studies. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for details of the review process is shown in Figure 1. All studies were published as full text articles. Pooled estimates were calculated by the fixed and random effect model. Fixed effect model was preferred to a random effect model for better accuracy based on the nature of individual study characteristics and heterogeneity.

Total number of patients included in this meta-analysis was 2651. Number of patients in the early cholecystectomy group was 1336, while that in the late cholecystectomy group was 1315. Median age of patients in the early cholecystectomy group was 43.6 years while that in the late group was 43.8. The P for Chi-squared heterogeneity for all the pooled accuracy estimates was > 0.10. The agreement between reviewers for collected data gave a Cohen’s κ value of 1.0.

Risk of conversion to open cholecystectomy: The pooled risk difference for conversion to open cholecystectomy was higher by 1.42% (95%CI: -0.35 to 3.21) in delayed cholecystectomy group as compared to early cholecystectomy group. This was statistically insignificant. Publication bias calculated using Begg-Mazumdar indicator gave Kendall’s tau b value of -0.019 (P = 0.88). Publication bias calculated using Harbord-Egger bias indicator gave a value of 0.56 (P = 0.23). Heterogeneity calculated using I2 statistic was 0 indicating no significant heterogeneity. Funnel plot assessing publication bias is shown in Figure 2.

Biliary complications: Biliary complications included recurrent pancreatitis, acute cholecystitis, acute cholangitis, biliary colic, jaundice, and common bile duct injury occurring while the patient is awaiting surgery. Pooled risk difference for biliary complications was higher by 10.76% (95%CI: 8.51 to 13.01) in the delayed cholecystectomy group as compared to those who underwent early cholecystectomy. Forrest plot of individual and pooled risk differences is shown in Figure 3.

Intraoperative complications: Intraoperative complications were defined as bile duct injury during surgery or intraoperative bleeding requiring transfusion. In the pooled patient population, the proportion of patients with intra-op complications was higher in the late cholecystectomy group by 0.41% (95%CI: -1.58 to 0.75) as compared to the early group. This difference was statistically insignificant.

Postoperative complications: Post-operative complications included bile leak, post-op bleeding requiring transfusion, pancreatitis, pseudocyst, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, or other systemic complications. Pooled risk difference of post op complications did not differ significantly between 2 groups, the trend was slightly higher in the late cholecystectomy group by 0.60% (95%CI: - 2.21 to 1.00) as compared to the early cholecystectomy group.

Length of stay: Pooled analysis showed late laparoscopic cholecystectomy group was associated with an increased length of stay by 88.96 h (95%CI: 86.31 to 91.62) as compared to early cholecystectomy group.

Duration of surgery: Pooled analysis showed the duration of surgery to be prolonged in the delayed cholecystectomy group by 39.11 min (95%CI: 37.44 to 40.77) as compared to the early group.

Early cholecystectomy has been recommended by various societies for treatment of gallstone pancreatitis. However, the rate of early cholecystectomy is reported to be around 9%-23% during index admission[16,17]. The reasons for these low outcomes is likely multifactorial including lack of operating room availability, budget restraints and the notion that early cholecystectomy could lead to increase in surgical complications citing increased edema in the setting of acute inflammation[16,18]. Previous studies have demonstrated that delayed cholecystectomy could not only lead to increased health care burden but also increased risk of pancreatitis reported to be up to 14%-31% if surgery is delayed[16,19,20]. To our knowledge, this is the largest meta-analysis so far with inclusion of most recent studies.

Our results demonstrated no significant difference in intraoperative and postoperative complications between early and late laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This is in consistence with other recent meta-analysis which have shown the difference of intraoperative and postoperative complications to be minimal whether cholecystectomy performed earlier or late post gallstone pancreatitis. However, our results differed from previous meta-analysis as biliary complications were noted to be significantly higher in our patients who underwent delayed cholecystectomy, by almost 10%. Yang et al[21] had recently demonstrated no significant difference in biliary complications between early and late cholecystectomy group (OR: 0.62). Similarly, Lyu et al[22] in their meta-analysis comprising almost 913 patients also showed no difference in biliary complications between early and late cholecystectomy groups. The etiology for this difference while unclear could be related to difference in inclusion criteria for biliary complications for each meta-analysis or more randomized controlled trial (RCT) being included in our meta-analysis. In a meta-analysis of only randomized controlled trials, Moody et al[5] had also demonstrated risk of biliary complications to be almost 20% in patients who underwent delayed cholecystectomy. Biliary complications included in our meta-analysis included recurrent pancreatitis, acute cholecystitis, acute cholangitis, biliary colic, jaundice, and common bile duct injury occurring while the patient is awaiting surgery. While biliary colic is reported to be the most common reason for readmission, recurrent pancreatitis remains the most feared. Readmission rates of up to 21% have been reported secondary to biliary complications in patients undergoing delayed cholecystectomy previously[23]. The most recent randomized controlled trial included in our meta-analysis from the United States reported low complication rates for both early and late cholecystectomy (6% vs 2%; P = 0.617)[24]. Biliary complications in the delayed group included recurrence/progression of pancreatitis in one patient while one patient in early cholecystectomy group had a stump leak and two had worsening/recurring pancreatitis[24]. Moreover, the early group was associated with significantly shorter length of hospital stay and decreased need for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography[24].

It was initially postulated that early cholecystectomy could lead to increased conversion to open cholecystectomy due to edema and adhesions[25]. However, our meta-analysis showed the rate of conversion to open cholecystectomy did not differ significantly between groups. Our results are in concordance with previous meta-analysis in which there have not reported any significant risk of conversion to open chole whether surgery carried out earlier or later[5,21,22]. Most recent RCTs continued to show no increase in risk of conversion to open cholecystectomy in either group[24,26,27].

Length of stay was reported to be longer by 88 h in the late cholecystectomy group as compared to early group. Previously Johnstone et al[18] have shown a difference of length of stay of almost 48 h between patients who underwent early cholecystectomy as opposed to those who undergo delayed cholesytectomy. Most recent randomized control trials by Riquelme et al[26] and Mageed et al[27] both reported decreased length of stay for early cholecystectomy group. This remains of pivotal importance as decreased length of stay is likely associated with decreased health care costs for these patients. Cost analysis studies have previously shown that early cholecystectomy tends to be associated with statistically significant cost difference of up to 795 pounds if performed within the first 3 d and up to 1003 pounds if performed during same admission as compared to delayed cholecystectomy[28].

Operative time was noted to be prolonged by 39 min in the delayed cholecystectomy group as compared to the early group. Zhong et al[7] had previously demonstrated no difference between operative time in early cholecystectomy and late cholecystectomy. The etiology for this longer duration of surgery in the delayed group, while exactly unclear, could be related to adhesions between gall bladder and surrounding tissue obscuring anatomy leading to difficult dissection[25,29]. Early cholecystectomy has been reported to be relatively more time saving as the edema in the early setting may make visualization of anatomical landmarks like Calots triangle easier[25].

Limitation of our meta-analysis includes different criteria used for diagnosis of mild pancreatitis in different studies which could reflect the difference of severity between different populations. Definitions of early cholecystectomy varied between different studies ranging from 24 h into admission to 2 wk post discharge. Similarly, there was significant heterogeneity between definition of delayed cholecystectomy varying from 2-6 wk post discharge.

The median age of patients included in most of these studies, is around 40-50, thus this data may be cautiously generalized to elderly patients who could be at increased risk of complications. Moreover, the data regarding comorbidities in patients undergoing cholecystectomy was also not evaluated. Nationwide Swedish analysis had suggested only 30%-40% of elderly received cholecystectomy in 1 year leading to increased complications[17]. We recommend a cautious and calculated approach in elderly and patients with complications and timings to be deemed as suitable per surgeon’s expertise.

In conclusion, in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis, early cholecystectomy may be preferred as it is safe, effective, and decreases complications associated with delayed cholecystectomy. Moreover, it also decreases operating time. However, caution should be observed to generalize our results, especially in elderly population as there seems to be a paucity of literature. More studies are needed in this regard to draw further concrete conclusions regarding optimal timing of cholecystectomy.

Gall stone pancreatitis is one of the most common causes of acute pancreatitis (30%-50%). Cholecystectomy remains the definitive treatment of choice for gallstone pancreatitis.

While, most of the major societies recommend early cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis, the rate of early cholecystectomy during index admission remains low due to perceived increased risk of complications.

The aim of our updated meta-analysis was to compare the length of stay, duration of surgery, biliary complications, conversion to open cholecystectomy, intra-operative, and post-operative complications between patients who underwent early cholecystectomy vs those who underwent late cholecystectomy.

Study Selection Criteria: Prospective, retrospective and randomized controlled trials comparing outcomes of early (surgery within the 2 wk of pancreatitis ) vs late cholecystectomy in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis were included in this analysis. Pooled proportions were calculated using both Mantel-Haenszel method (fixed effects model) and DerSimonian Laird method (random effects model). The heterogeneity among studies was tested using Cochran’s Q test based upon inverse variance weights.

Eighteen studies (n = 2651) were included in this analysis. Late laparoscopic cholecystectomy was associated with an increased length of stay by 88 h comparted to early group (95%CI: 86.3 to 91.6). Late group also had an increased duration of surgery by 39 min compared to early group (95%CI: 37.4 to 40.7). Risk of biliary complications was 10.76 % higher in late cholecystectomy group as compared to later group (95%CI: 8.51 to 13.01). The chances of conversion to open cholecystectomy was 1.42 % higher in the delayed surgery.

In conclusion, early cholecystectomy appears to be not only safe but also may be associated with shorter length of stay and duration of surgery as compared to late cholecystectomy. The rate of complications also appear to higher in patients who undergo late cholecystectomy with higher chances of conversion to open cholecyste-ctomy.

The definition of early cholecystectomy remains variable in different studies, moreover there is paucity of studies with elderly population which are at higher risk of complications. Future studies should be more focused to determine optimal timing of surgery after an attack of acute pancreatitis, also outcomes of early cholecystecotmy in elderly populations need to be further studied.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Brisinda G, Spiliopoulos S S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Zilio MB, Eyff TF, Azeredo-Da-Silva ALF, Bersch VP, Osvaldt AB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the aetiology of acute pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21:259-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, Falck-Ytter Y, Barkun AN; American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on Initial Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1096-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 79.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2006;33:323-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ragnarsson T, Andersson R, Ansari D, Persson U, Andersson B. Acute biliary pancreatitis: focus on recurrence rate and costs when current guidelines are not complied. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:264-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moody N, Adiamah A, Yanni F, Gomez D. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of early versus delayed cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2019;106:1442-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Matta B, Gougol A, Gao X, Reddy N, Talukdar R, Kochhar R, Goenka MK, Gulla A, Gonzalez JA, Singh VK, Ferreira M, Stevens T, Barbu ST, Nawaz H, Gutierrez SC, Zarnescu NO, Capurso G, Easler J, Triantafyllou K, Pelaez-Luna M, Thakkar S, Ocampo C, de-Madaria E, Cote GA, Wu BU, Paragomi P, Pothoulakis I, Tang G, Papachristou GI. Worldwide Variations in Demographics, Management, and Outcomes of Acute Pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 1567-1575. e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhong FP, Wang K, Tan XQ, Nie J, Huang WF, Wang XF. The optimal timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ranson JH, Rifkind KM, Roses DF, Fink SD, Eng K, Spencer FC. Prognostic signs and the role of operative management in acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;139:69-81. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4323] [Article Influence: 360.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 10. | Balthazar EJ. Acute pancreatitis: assessment of severity with clinical and CT evaluation. Radiology. 2002;223:603-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 534] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Louis C, Diekmann L, Brisse B, Müller KM. [Report of pheochromocytoma in childhood (author's transl)]. Z Kinderheilkd. 1975;119:197-210. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006;25:3443-3457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1463] [Cited by in RCA: 1701] [Article Influence: 89.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088-1101. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1519] [Cited by in RCA: 1570] [Article Influence: 65.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in RCA: 2635] [Article Influence: 109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van Baal MC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, Schaapherder AF, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Gooszen HG, van Ramshorst B, Boerma D; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Timing of cholecystectomy after mild biliary pancreatitis: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2012;255:860-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sandzén B, Haapamäki MM, Nilsson E, Stenlund HC, Oman M. Cholecystectomy and sphincterotomy in patients with mild acute biliary pancreatitis in Sweden 1988 - 2003: a nationwide register study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Johnstone M, Marriott P, Royle TJ, Richardson CE, Torrance A, Hepburn E, Bhangu A, Patel A, Bartlett DC, Pinkney TD; Gallstone Pancreatitis Study Group; West Midlands Research Collaborative. The impact of timing of cholecystectomy following gallstone pancreatitis. Surgeon. 2014;12:134-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hwang SS, Li BH, Haigh PI. Gallstone pancreatitis without cholecystectomy. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:867-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hernandez V, Pascual I, Almela P, Añon R, Herreros B, Sanchiz V, Minguez M, Benages A. Recurrence of acute gallstone pancreatitis and relationship with cholecystectomy or endoscopic sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2417-2423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yang DJ, Lu HM, Guo Q, Lu S, Zhang L, Hu WM. Timing of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy After Mild Biliary Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28:379-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lyu YX, Cheng YX, Jin HF, Jin X, Cheng B, Lu D. Same-admission versus delayed cholecystectomy for mild acute biliary pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2018;18:111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cameron DR, Goodman AJ. Delayed cholecystectomy for gallstone pancreatitis: re-admissions and outcomes. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:358-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mueck KM, Wei S, Pedroza C, Bernardi K, Jackson ML, Liang MK, Ko TC, Tyson JE, Kao LS. Gallstone Pancreatitis: Admission Versus Normal Cholecystectomy-a Randomized Trial (Gallstone PANC Trial). Ann Surg. 2019;270:519-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sinha R. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute biliary pancreatitis: the optimal choice? HPB (Oxford). 2008;10:332-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Riquelme F, Marinkovic B, Salazar M, Martínez W, Catan F, Uribe-Echevarría S, Puelma F, Muñoz J, Canals A, Astudillo C, Uribe M. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy reduces hospital stay in mild gallstone pancreatitis. A randomized controlled trial. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22:26-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mageed SA, Helmy MZ, Redwan AA. Acute mild gallstone pancreatitis: timing of cholecystectomy. Int Surg J. 2019;6:1051-1055. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Morris S, Gurusamy KS, Patel N, Davidson BR. Cost-effectiveness of early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for mild acute gallstone pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101:828-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Aksoy F, Demiral G, Ekinci Ö. Can the timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy after biliary pancreatitis change the conversion rate to open surgery? Asian J Surg. 2018;41:307-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |