Published online Apr 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2649

Peer-review started: December 12, 2020

First decision: December 24, 2020

Revised: December 26, 2020

Accepted: January 27, 2021

Article in press: January 27, 2021

Published online: April 16, 2021

Processing time: 111 Days and 1.7 Hours

Laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy (LLDH) has been successfully carried out in several transplant centers. Biliary reconstruction is key in living donor liver transplantation (LDLT). Reliable biliary reconstruction can effectively prevent postoperative biliary stricture and leakage. Although preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and intraoperative indocyanine green cholangiography have been shown to be helpful in determining optimal division points, biliary variability and limitations associated with LLDH, multiple biliary tracts are often encountered during surgery, which inhibits biliary reconstruction. A reliable cholangiojejunostomy for multiple biliary ducts has been utilized in LDLT. This procedure provides a reference for multiple biliary reconstructions after LLDH.

A 2-year-old girl diagnosed with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency required liver transplantation. Due to the scarcity of deceased donors, she was put on the waiting list for LDLT. Her father was a suitable donor; however, after a rigorous evaluation, preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography examination of the donor indicated the possibility of multivessel variation in the biliary tract. Therefore, a laparoscopic left lateral section was performed on the donor, which met the estimated graft-to-recipient weight ratio. Under intraoperative indocyanine green cholangiography, 4 biliary tracts were confirmed in the graft. It was difficult to reform the intrahepatic bile ducts due to their openings of more than 5 mm. A reliable cholangiojejunostomy was, therefore, utilized: Suture of the jejunum to the adjacent liver was performed around the bile duct openings with 6/0 absorbable sutures. At the last follow-up (1 year after surgery), the patient was complication-free.

Intrahepatic cholangiojejunostomy is reliable for multiple biliary ducts after LLDH in LDLT.

Core Tip: A patient diagnosed with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency required liver transplant surgery. After developing a binding surgical plan, we decided to perform a living-donor liver transplantation, using a laparoscopic donor liver resection. However, multiple biliary tracts were observed. We used “Plug-in” anastomosis for cholangio-jejunostomy and received satisfactory results.

- Citation: Xiao F, Sun LY, Wei L, Zeng ZG, Qu W, Liu Y, Zhang HM, Zhu ZJ. Cholangiojejunostomy for multiple biliary ducts in living donor liver transplantation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(11): 2649-2654

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i11/2649.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2649

Biliary anastomosis is key in living donor liver transplantation (LDLT), with biliary complications varying from 5% to 40%. Biliary leaks and strictures are common complications. According to research, biliary complication rates of up to 53.7%, with anastomotic strictures occupying 41.5% of the complications[1,2] were reported. Depending on laparoscopic surgical skills of resident surgeons, laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy (LLDH) has been performed in some transplant centers[3]. Due to biliary anatomic variations and laparoscopic surgical limitations[4], multiple hepatic duct orifices are often seen during surgery. A technical problem of bile duct reconstruction during LDLT, is caused by multiple biliary ducts that receive a poor blood supply from both donor and recipient[5]. The impact of various graft biliary orifices on biliary complications in the recipient have not been established[6]. The results of those receiving grafts with a single or paired bile ducts were compared in recent research. It was observed that living donor grafts with 2 biliary ducts are safe and have no negative influence on biliary complication rates after 1-year of follow-up[7]. At another center, multiple anastomoses were performed during surgery. At a median follow-up of 36 mo, the biliary complication rate was 16.9%, greater than that with one biliary duct[8]. This study describes cholangiojejunostomy for multiple biliary ducts during LDLT.

A 2-year-old girl was admitted to our center with complaints of hyperammonemia and lethargy for 4 mo.

For four months, the patient had experienced lethargy and intermittent abdominal pain. After seeing doctors in local hospitals, she was diagnosed with hyper-ammonemia. However, the disease could not be cured at local hospitals, therefore, she gradually developed liver failure.

The patient had no significant medical history and chronic diseases were denied.

No significant personal and family medical history.

According to her physical examination, confusion, disorientation, and amnesia were noted. Muscular rigidity, nystagmus, overt hepatic encephalopathy and Grade III hepatic disease were also observed.

Genetic testing revealed ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD). Laboratory examinations upon admission revealed blood NH3 level of 153 µmol/L, alanine aminotransferase (83 U/L), albumin (24.9 g/L), total bilirubin (4.8 µmol/L), direct bilirubin (0.5 µmol/L) and creatinine (4.3 µmol/L). Her prothrombin time was 19.50 s compared to the normalized ratio of 1.52.

Abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography were unremarkable. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) examination of the donor indicated the possibility of multivessel variation in the biliary tract (Figure 1).

Based on the above findings, OTCD was diagnosed.

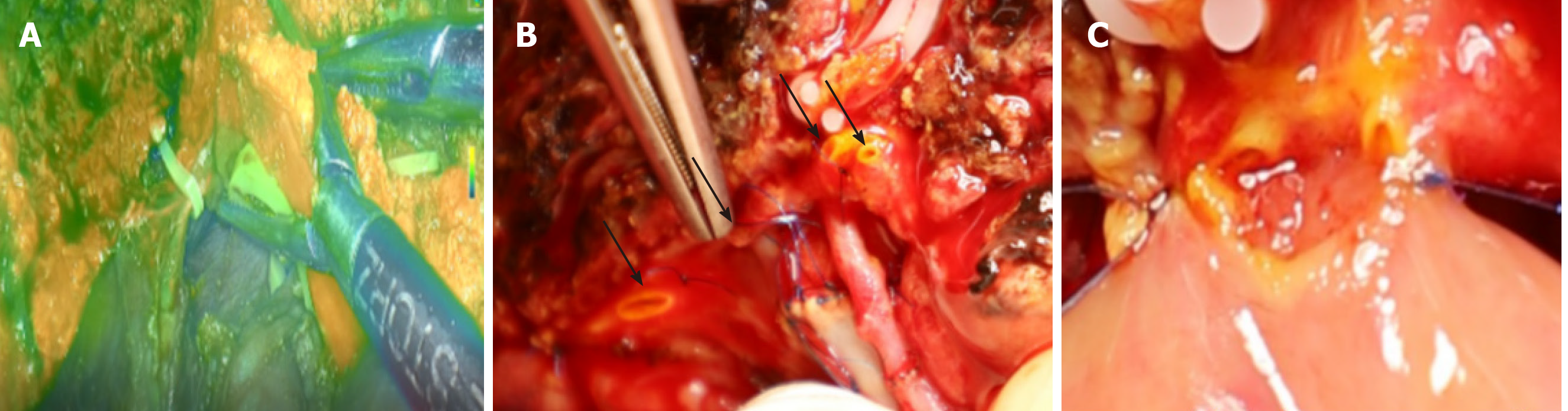

OTCD is a metabolic disease, protein diet restriction and medications that stimulate the removal of nitrogen from the body may prevent progression of the disease. Unfortunately, these measures cannot prevent the emergence of hyperammonemia and metabolic encephalopathy; thus, liver transplantation is indicated. Due to the scarcity of deceased donors, we proposed a laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy in donors for liver transplantation among children. The liver graft includes the left lateral section (segments 2 and 3 based on Couinaud’s classification), left branch of the hepatic artery and left portal branch, left bile duct, and left hepatic vein. Preoperative MRCP evaluation of donor biliary anatomy indicated bile duct variations (Figure 1). Intraoperative indocyanine green near-infrared fluorescence cholangiography was routinely performed (Figure 2A), and 4 biliary tracts were confirmed in the graft (Figure 2B), which inhibited bile duct reconstruction. The intrahepatic bile ducts cannot be joined because the gap between the two openings was too large. Suture of the jejunum to the nearby liver was performed around the bile duct opening with 6/0 absorbable sutures (Figure 2C). Surgical procedures were successfully completed after 6 h.

Ten days after surgery, the levels of serum total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase were close to normal. The absence of bile leakage within 1 wk necessitated the removal of the abdominal drainage tube and antibiotic prophylaxis (Sulbactam and Cefoperazone) was used 8 d after surgery. One year after surgery, there was no anastomotic stricture or cholangitis.

Cherqui et al[9] indicated the feasibility of laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy in pediatric LDLT. The laparoscopic approach can be used as normal practice for harvesting left lateral lobe liver grafts[10]. A meta-analysis revealed that LLDH is a secure and efficient option for LDLT, which enhances the donors’ perioperative results compared with open living donor hepatectomy[11]. However, this technique is hampered by bile duct complications, especially in LLDH. Multiple factors lead to bile duct complications. One of the most important reasons is that LLDH can cause multiple bile ducts, which are a problem for the cholangiojejunostomy. Common biliary complications include stricture, leakage, obstruction, and stone formation. Deka et al[12] revealed that the length of the left hepatic duct varied from 1.2 mm to 30.36 mm with a median value of 6.83 mm, which shows that the length of the left hepatic duct in half of the patients varied from 1.2 mm to 6.83 mm. Moreover, preoperative MRCP and direct intraoperative vision decides the division of the bile duct. However, it is not sufficient to determine the optimal cut-off point by these procedures as it is difficult to identify the left hepatic duct by direct vision and real-time positioning is impossible by preoperative MRCP. Hence, the surgeon may inadvertently cut too much to the left, to ensure that there is sufficient safety distance on the donor side, and sacrifice part of the length of the bile duct using Hemlok to cut the bile duct, leading to multiple orifices in the graft side.

Four bile ducts were found during surgery, thereby, making the duct-to-duct bile duct reconstruction impossible. Therefore, hepaticojejunostomy was considered. However, it is difficult to reconstruct the biliary tract with multiple orifice anastomoses, and the incidence of biliary stenosis and bile leakage are higher than normal[13]. The pelvic anastomosis of multiple bile ducts adjacent to the hepatic duct stump, can effectively solve the problem of postoperative anastomotic stenosis. However, complications such as bile leakage are higher. Adjacent bile ducts subjected to plastic surgery have changed the physiological direction of the bile duct. The portal vein is compressed by biliary dilatation within the confines of the Glisson sheath, which leads to portal hypertension and persistent cholestasis, and increases the risk of cholangitis and septic events in the postoperative period. We used a “Plug-in” technique for bile duct anastomosis. Suture of the jejunum to the nearby liver was performed around the bile duct openings with intermittent 6/0 absorbable sutures. The jejunum was anastomosed with the liver tissue around the bile duct, and multiple bile duct openings were embedded in the jejunum. During the procedure, the anterior wall of the jejunum should be sutured as close as possible to the liver tissue above the anterior wall of the bile duct, in order to improve the migration of the jejunal mucosa through the liver section to the bile duct. To ensure suturing of the anastomosis, it is necessary to determine the position of each needle, especially during posterior wall anastomosis, to prevent the suture needle from penetrating the portal vein. Intermittent suture of the front wall of the anastomosis requires the inversion of the intestinal mucosa into the anastomosis, which is one of the important measures for preventing biliary leakage. Another key operation in the anastomosis is that the stitch length of the anastomotic suture and the tension of the knot is uniform. The needle can be inserted deeper when suturing, and the knot should not be too tight to prevent splitting the liver tissue. During the anastomosis, suture, traction and ligation should be gentle to avoid tearing the jejunum.

Laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy can be used in living donor liver transplantation but can lead to an increase in the number of bile ducts. The “Plug-in” cholangiojejunostomy for multiple biliary ducts is a reliable anastomosis technique.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Qiao Z, Sintusek P S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Abu-Gazala S, Olthoff KM, Goldberg DS, Shaked A, Abt PL. En Bloc Hilar Dissection of the Right Hepatic Artery in Continuity with the Bile Duct: a Technique to Reduce Biliary Complications After Adult Living-Donor Liver Transplantation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:765-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rhu J, Kim JM, Choi GS, David Kwon CH, Joh JW. Impact of Extra-anatomical Hepatic Artery Reconstruction During Living Donor Liver Transplantation on Biliary Complications and Graft and Patient Survival. Transplantation. 2019;103:1893-1902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li H, Wei Y, Li B. Total laparoscopic living donor right hemihepatectomy: first case in China mainland and literature review. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4622-4623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wybourn CA, Kitsis RM, Baker TA, Degner B, Sarker S, Luchette FA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia: Which patients have long term benefit? Surgery. 2013;154:761-7; discussion 767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chok KS, Lo CM. Biliary complications in right lobe living donor liver transplantation. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:553-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakamura T, Iida T, Ushigome H, Osaka M, Masuda K, Matsuyama T, Harada S, Nobori S, Yoshimura N. Risk Factors and Management for Biliary Complications Following Adult Living-Donor Liver Transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2017;22:671-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kollmann D, Goldaracena N, Sapisochin G, Linares I, Selzner N, Hansen BE, Bhat M, Cattral MS, Greig PD, Lilly L, McGilvray ID, Ghanekar A, Grant DR, Selzner M. Living Donor Liver Transplantation Using Selected Grafts With 2 Bile Ducts Compared With 1 Bile Duct Does Not Impact Patient Outcome. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:1512-1522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bhangui P, Saha S. The high-end range of biliary reconstruction in living donor liver transplant. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2019;24:623-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cherqui D, Soubrane O, Husson E, Barshasz E, Vignaux O, Ghimouz M, Branchereau S, Chardot C, Gauthier F, Fagniez PL, Houssin D. Laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy for liver transplantation in children. Lancet. 2002;359:392-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim KH, Jung DH, Park KM, Lee YJ, Kim DY, Kim KM, Lee SG. Comparison of open and laparoscopic live donor left lateral sectionectomy. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1302-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xu J, Hu C, Cao HL, Zhang ML, Ye S, Zheng SS, Wang WL. Meta-Analysis of Laparoscopic vs Open Hepatectomy for Live Liver Donors. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Deka P, Islam M, Jindal D, Kumar N, Arora A, Negi SS. Analysis of biliary anatomy according to different classification systems. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014;33:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Gonen M, Burke EC, Bodniewicz BS J, Youssef BA M, Klimstra D, Blumgart LH. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507-517; discussion 517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 973] [Cited by in RCA: 964] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |