Published online Apr 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2602

Peer-review started: December 6, 2020

First decision: January 10, 2021

Revised: January 19, 2020

Accepted: February 9, 2021

Article in press: February 9, 2021

Published online: April 16, 2021

Processing time: 115 Days and 19 Hours

Spontaneous renal rupture is a rare disease in the clinic. The causes of spontaneous renal rupture include extrarenal factors, intrarenal factors, and idiopathic factors. Reports on infection secondary to spontaneous renal rupture and the complications of spontaneous renal rupture are scarce. Furthermore, there are few patients with spontaneous renal rupture who present only with fever.

We present the case of a 52-year-old female patient who was admitted to our hospital. She presented only with fever, and the cause of the disease was unclear. She underwent a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan, which showed that the left renal capsule had a crescent-shaped, low-density shadow; the perirenal fat was blurred, and exudation was visible with no sign of calculi, malignancies, instrumentation, or trauma. Under ultrasound guidance, a pigtail catheter was inserted into the hematoma, and fluid was drained and used for the bacterial test, which proved the presence of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Two months later, abdominal CT showed that the hematoma was absorbed, so the drainage tube was removed. The abdominal CT was normal after 4 mo.

Spontaneous renal rupture due to intrarenal factors causes a higher proportion of shock and is more likely to cause anemia.

Core Tip: Spontaneous rupture of the kidney is uncommon in the clinic. The causes of spontaneous renal rupture include extrarenal factors, intrarenal factors, and idiopathic factors. We present a case whose symptoms were atypical and who presented only with fever. The cause of the disease was unclear. Infection secondary to the perinephric hematoma was shown, with clear etiological evidence of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. This case highlights the importance of identifying the cause and determining the location of the rupture, and the treatment can be given according to the causative pathogen. Moreover, more attention should be paid to comorbidities, especially those caused by intrarenal factors, which are more fatal than other factors.

- Citation: Zhang CG, Duan M, Zhang XY, Wang Y, Wu S, Feng LL, Song LL, Chen XY. Klebsiella pneumoniae infection secondary to spontaneous renal rupture that presents only as fever: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(11): 2602-2610

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i11/2602.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2602

Spontaneous rupture of the kidney is extremely rare. Causative factors leading to spontaneous renal rupture include urinary calculi, malignancies, instrumentation, or trauma. It can occur in the renal parenchyma, collecting system, or renal blood vessels and is often in either the pathological or normal kidney. The symptoms vary according to different parts and times of occurrence. We report a patient with spontaneous renal rupture with an unknown cause.

A 52-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital’s emergency department with a fever for 13 d and no cough, abdominal pain, nausea, or diarrhea.

The patient did not have chronic diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease.

The patient underwent hysterectomy 2 decades ago.

The patient had no remarkable personal and family history. She does not take drugs in daily life.

The patient’s vital signs were as follows: Blood pressure, 133/74 mmHg; pulse, 78 beats per minute and regular; blood glucose, 6.0 mmol/L; and temperature, 39.2 °C. On physical examination, her abdomen was soft, with no tenderness, rebound pain, or percussion pain in the liver or kidney areas.

Routine blood test results showed the following: White blood cell (WBC) count, 12.24 × 109/L; percentage of neutrophilic granulocytes, 85.6%; hemoglobin concentration, 93 g/L; platelets, 358000/mL; and C-reactive protein, 138 U/mL. The blood chemistry examination, glycosylated hemoglobin, coagulation profile, and extractable nuclear antigens were within normal limits. Urinalysis showed urinary protein 1+, urinary WBC 3+, and nitrite negativity, and bacteria were not found in the urine or blood.

First, we considered the possibility of an infectious disease, but the site of infection was unclear. The patient underwent blood tests, X-ray of the chest, abdominal ultrasound, and urine tests to investigate the infection site. Chest X-ray revealed normal findings.

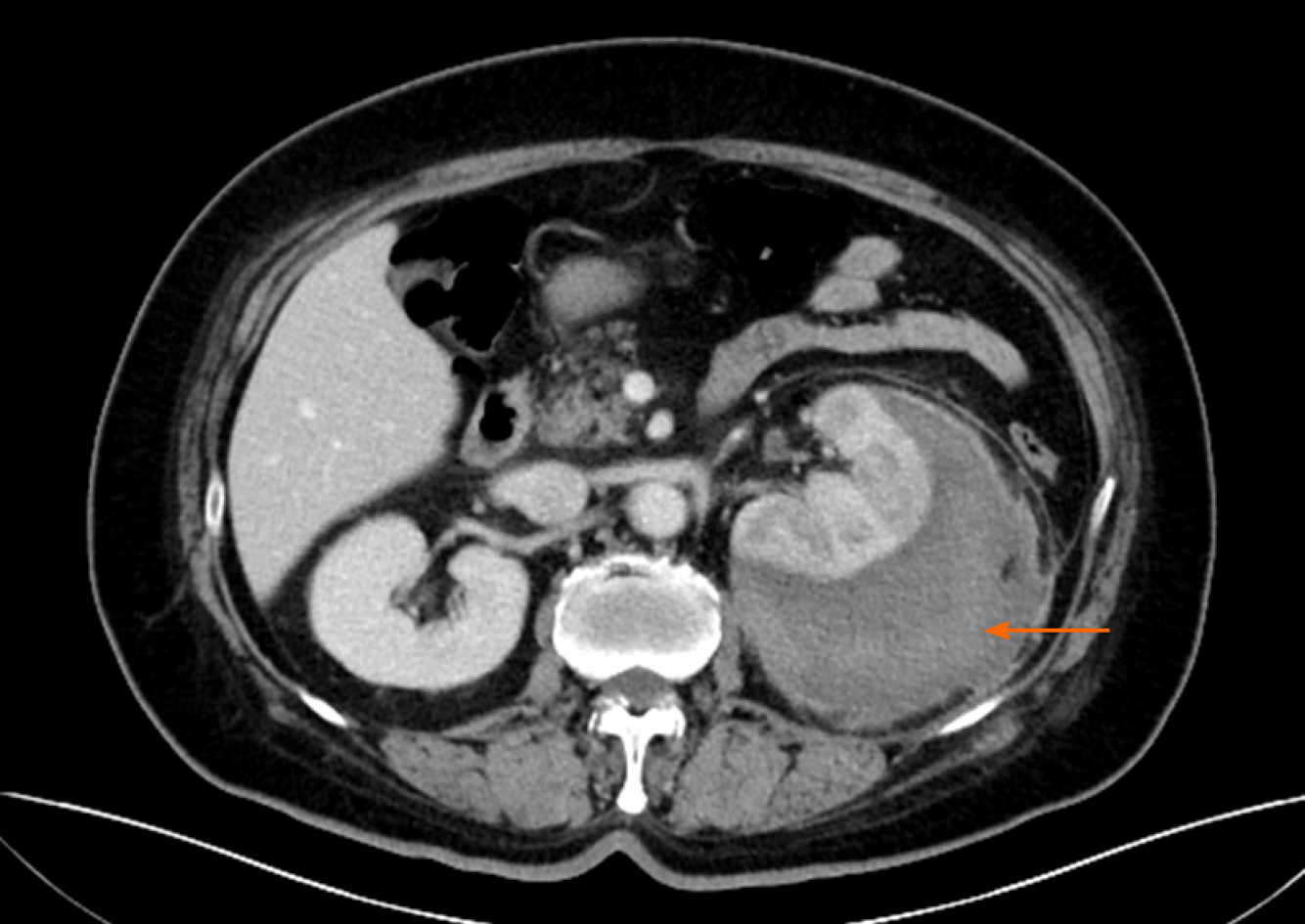

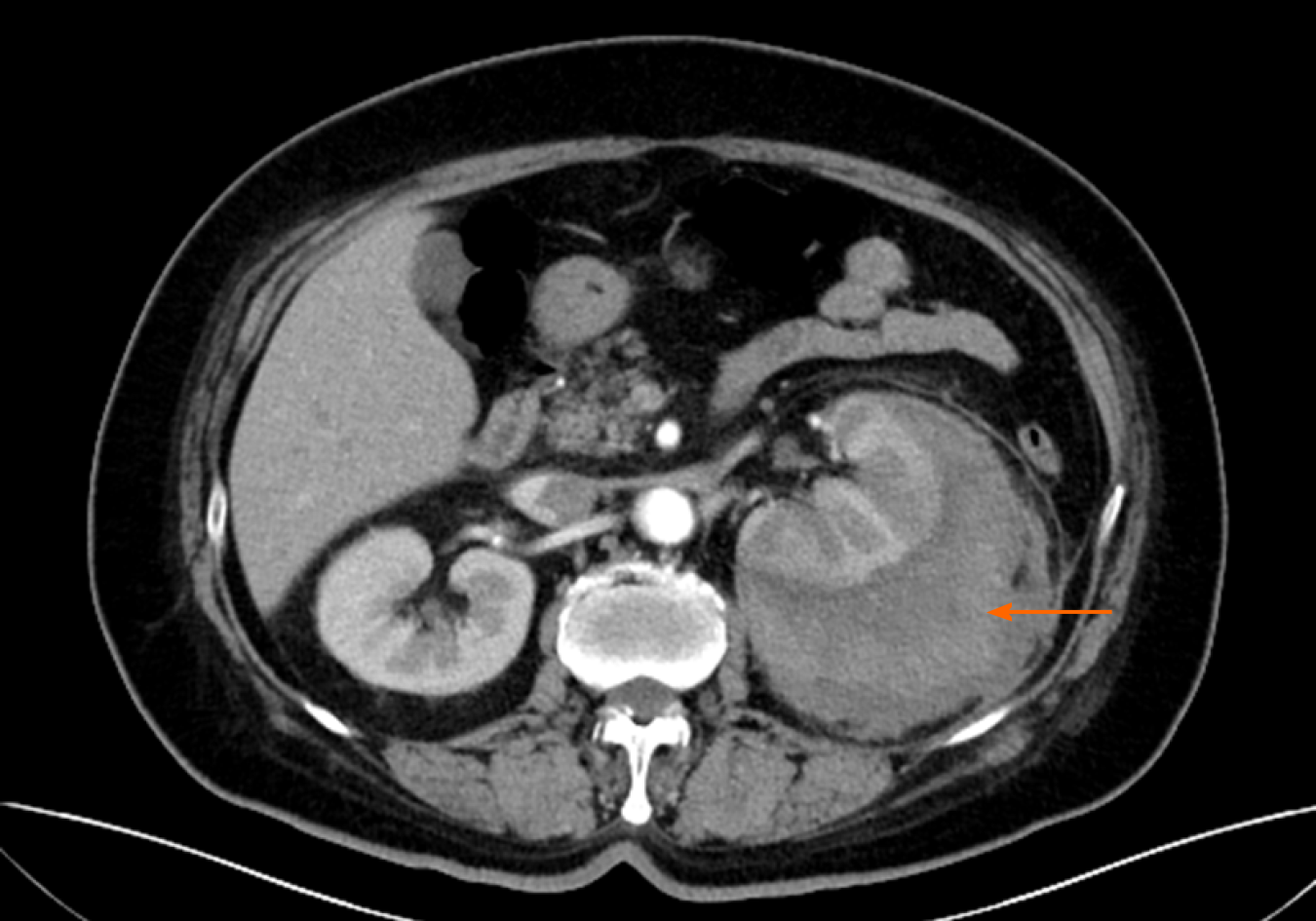

Around the left kidney, abdominal ultrasound showed a visible, liquid, dark area. To distinguish whether there was a perirenal abscess, hematoma, or tumor, the patient underwent a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan, which showed atrophy of the left kidney. The left renal capsule had a crescent-shaped, low-density shadow, and the CT value of the contrast-enhanced scan without enhancement was 53 HU, with no enhancement observed on the contrast-enhanced scan (contrast agent, iodohydril; CT value, 100 HU) (Figures 1 and 2). The perirenal fat was blurred, and exudation was visible with no sign of calculi, malignancies, instrumentation, or trauma (Figures 1-3). Inflammation was considered to be secondary to rupture of the left kidney and extravasation of urine.

Under ultrasound guidance, a pigtail catheter was inserted into the hematoma, and 150 mL in total of fluid was drained and used for the bacterial test. The appearance was hemorrhagic, thick, and brown, indicating a Gram-negative bacterial infection, which was then proved to be caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae (Table 1) 3 d later. We considered the source of inflammation to be the hematoma, which had existed for a long time and led to chronic infection according to the normal urine and blood culture results.

| Antibiotic | Result |

| Ampicillin | R |

| Cefazolin | S |

| Ceftriaxone | S |

| Ertapenem | S |

| Imipenem | S |

| Amikacin | S |

| Levofloxacin | S |

| Tigecycline | S |

| Cefoperazone/Sulbactam | S |

The final diagnosis of the presented case was Klebsiella pneumoniae infection secondary to spontaneous renal rupture.

The patient underwent a bed rest and anti-infection treatment with ceftriaxone (2 g once per day) for 1 wk, with hemostasis and fluid support.

The patient’s temperature returned to normal, and she had no sign of visible discomfort the next day. Three days later, the patient returned for a CT scan, which showed that the hematoma had decreased and that there was no tumor. Two months later, abdominal CT showed that the hematoma was absorbed, and the drainage tube was removed. Abdominal CT findings were normal after 4 mo.

Spontaneous rupture of the kidney is uncommon in the clinic. The causes of spontaneous renal rupture include extrarenal factors, intrarenal factors, and idiopathic factors. A search was performed in PubMed with “spontaneous renal rupture” as the key word, and 15 case reports from 2004 to 2018 were reviewed. These 15 case reports are summarized in Table 2. We divided the cases into three categories: Extrarenal factors (option A), intrarenal factors (option B), and idiopathic factors (unknown causes) (option C). The extrarenal factors included urinary stones, third trimester of pregnancy, and urinary retention. Intrarenal factors included tumor and vascular factors (Tables 3-5). Due to the rapid increase in intrarenal pressure, extrarenal factors often lead to renal pelvis rupture (Table 3). The rupture site is the fornix, followed by the upper ureter, when pressure exceeds a critical level reported to be from 20-75 mmHg[1]. The common causes are obstruction (urinary stones[2-4], third trimester of pregnancy[5,6], and papillary necrosis) and urinary retention[7]. Urinary stones are the most common cause of renal pelvis rupture[8]. Akpinar et al[9] described 91 patients with spontaneous ureteral rupture, and 72% of patients had stone disease as the etiology. In particular, clinicians should be aware of papillary necrosis, which is hard to diagnose and known to be associated with sickle cell hemoglobinopathies and a wide range of etiologies[10]. Intrarenal factors include mainly vascular factors (immune system diseases, aneurysms, etc.), infections, and tumors, and they often lead to renal parenchyma rupture (Table 3)[11-14]. Zhang et al[15] summarized 165 patients with spontaneous repair of the renal parenchyma from 1985 to 1999 and found that tumor was the main cause, accounting for 61.5% of patients, while the vasculature accounted for 17% of patients and infection accounted for 2.4% of patients. The result is similar to that of the study by McDougal et al[16].

| Item | Description | Result |

| Gender | Male | 6/15 (40%) |

| Age | Year | (50.13 ± 19.77) |

| Symptom | Abdominal pain | 6/15 (40%) |

| Frank pain | 9/15 (60%) | |

| Cause | Urinary stones | 3/15 (20%) |

| Third trimester | 3/15 (20%) | |

| Tumor | 1/15 (7%) | |

| Vascular factor | 5/15 (33%) | |

| Retention | 2/15 (13%) | |

| Idiopathic | 1/15 (7%) | |

| Location | Renal pelvis | 8/15 (53%) |

| Renal parenchyma | 7/15 (47%) | |

| Anemia | Yes | 7/15 (47%) |

| No | 8/15 (53%) | |

| Shock | Yes | 5/15 (34%) |

| No | 10/15 (66%) | |

| Treatment | Embolism | 2/15 (13%) |

| Ureteral stent | 7/15 (47%) | |

| Puncture drainage | 3/15 (20%) | |

| Nephrectomy | 2/15 (13%) | |

| Conservative treatment | 1/15 (7%) | |

| Prognosis | Death | 1/15 (7%) |

| Recovery | 14/15 (93%) |

| Option A | Option B | Option C | Total | |

| Renal pelvis | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Renal parenchyma | 0 | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| Total | 8 | 6 | 1 | 15 |

| Option A | Option B | Option C | Total | |

| Yes | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| No | 7 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| Total | 8 | 6 | 1 | 15 |

| Option A | Option B | Option C | Total | |

| Yes | 1 | 6 | 0 | 7 |

| No | 7 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Total | 8 | 6 | 1 | 15 |

Symptoms of spontaneous rupture of the kidney can represent abdominal and flank pain, nausea, and vomiting. Sometimes, they are confused with retroperitoneal hematomas, which usually disguise them by imaging, such as CT scan[17]. Chen et al[18] showed that patients suffering from acute flank pain accounted for 66.7% of all cases, while patients with abdominal pain accounted for 33.3 [3]. These symptoms are similar to those from other papers in our review (Table 2). However, when our patient was admitted, she had a fever without abdominal or flank pain, nausea, or vomiting. The symptoms of our patient were not typical, and we considered the possibility of infectious diseases at the initial visit. We think that the reason for these atypical symptoms was that the patient had adapted to the feeling of discomfort, namely, the renal pain became less severe because the hemorrhage was chronic, lasting for a long time, and the patient gradually adapted to it. We confirmed the diagnosis by a CT scan. Therefore, clinicians should also be aware of patients with atypical symptoms and fully examine a patient to diagnose him or her.

Ultrasonography is a fast, safe, and inexpensive method to diagnose diseases[19,20]; however, it may be challenging to distinguish a tumor, an abscess, or a hematoma by this method. Moreover, flatulence can decrease the accuracy of ultrasonography. In 15 patients, 4 underwent ultrasound examination first with normal results. The ultrasonography results of one of the patients showed a problem that could not be clarified. The diagnoses of all of these patients were confirmed after the CT examination. CT examination can also determine whether there are urinary stones, tumors, trauma, and other factors. Furthermore, contrast-enhanced CT can help to determine whether there are vascular diseases. However, we should be aware of the possibility of leakage of contrast agent due to vascular damage. Even so, these patients’ CT images showed low-density liquid dark areas, and no enhancement was observed in the contrast-enhanced scans (Figures 1 and 2).

Treatment of the causes is essential. Patients with urinary obstruction should be provided with double-J catheter placement. Artery embolization can be chosen as the selective treatment if double-J catheter placement does not work[21]. For hematomas, percutaneous puncture for drainage and laparoscopic evacuation can be applied.

However, clinicians should pay attention to comorbidities such as shock, anemia, renal impairment, infection, and secondary abscess. As indicated in Tables 4 and 5, spontaneous hemorrhage caused by intrarenal factors causes a higher proportion of shock and is more likely to cause anemia. The reasons are spontaneous hemorrhage and intrarenal factors that cause damage to multiple organs over a long period, resulting in the patient becoming weaker and more tolerant. When hemorrhage occurs, the function of the body may become more serious. We can conclude that spontaneous renal rupture caused by intrarenal factors is more fatal, and more attention should be paid to this. However, due to the lack of patient information on renal function and infection status, we could not assess the damage to kidney function or inflammation, which is a limitation of this study.

Urinary tract obstruction is the most common reason for urinary tract infection[22,23]. The predominant pathogen is Escherichia coli (E. coli) (approximately 75% of cases, similar to Bahadin et al[24] research). However, there are other pathogens involved, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Proteus mirabilis. Bahadin et al[24] enrolled 333 patients and found that E. coli was the most common pathogen, accounting for 74.5% of patients, while Klebsiella pneumoniae was the next most common pathogen, accounting for 8.7% of patients. Our patient had renal rupture due to nonobstructive causes and a secondary infection of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Klebsiellae pneumoniae infection is common in patients with immune deficiency, especially in those with diabetes or impaired fasting glucose. For this patient, we considered the reason to be hemorrhage leading to anemia and chronic consumption leading to immune deficiency or retrograde infection along the urinary tract.

The commonly available antibiotics for Klebsiella pneumoniae in primary care are amoxicillin/clavulanate, ceftriaxone, cephalothin, ciprofloxacin (Cip), cotrimoxazole (Cot), and nalidixic acid (Nal). Bahadin et al[24] showed the sensitivity of Klebsiella pneumoniae to first-line antibiotics, as shown in Table 6. Gołębiewska et al[25] enrolled 54 patients and found that they developed 61 episodes of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Forty-one percent of them were diagnosed with only a single Klebsiella pneumoniae infection, while 59% suffered from recurrence. Moreover, 19 of them had multiple Klebsiella pneumoniae infections, while 13 patients had a history of reinfections with various pathogens. Moreover, attention should be paid to the antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae and the antibiotic should be adjusted in time[26]. We did not analyze the etiology distribution or costs among all the patients due to a lack of research, which is a deficiency of this review.

| Antibiotic | % Sensitivity |

| Cephalothin | 65.5 |

| Cotrimoxazole | 69.0 |

| Nalidixicacid | 69.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 72.4 |

| Amoxicilin/clavulanate | 82.8 |

| Gentamicin | 100.0 |

| Ceftriaxone | 86.2 |

| Aztreonam | 82.8 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 37.9 |

| Piperacilin/tazobactam | 89.7 |

| Ertapenem | 100.0 |

Our patient’s symptoms were atypical, and she presented only with fever. The cause of the disease was unclear. Infection secondary to the perinephric hematoma and clear etiological evidence led to a diagnosis of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a patient with idiopathic spontaneous rupture of the kidney who presented only with fever. This is also the first report of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection secondary to spontaneous rupture of the kidney. In clinical work, patients with unknown fever should be examined to determine the source of infection and the associated pathogens and then receive targeted treatment. If patients have renal rupture, further examination should be performed, especially CT, to distinguish whether there are extrarenal factors, intrarenal factors, or idiopathic factors.

Spontaneous renal rupture is rare in the clinic. For this disease, the cause and location of the rupture should be first determined. Then, treatment can be given according to the causative pathogen. Moreover, attention should be paid to comorbidities, especially those caused by intrarenal factors, which are more fatal than other factors.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Emergency medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Desai M, Zhou T S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Okamura A. [Long road to the hospice--the life of Mother Mary Aikenhead (17). Lyon to Paris: Hotel Dieu and the civil hospice]. Kango Kyoiku. 1985;26:104-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Searvance K, Jackson J, Schenkman N. Spontaneous Perforation of the UPJ: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Urol Case Rep. 2017;10:30-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jeon CH, Kang JH, Min JH, Park JS. Spontaneous Ureteropelvic Junction Rupture Caused by a Small Distal Ureteral Calculus. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128:3118-3119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang H, Zhuang G, Sun D, Deng T, Zhang J. Spontaneous rupture of the renal pelvis caused by upper urinary tract obstruction: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e9190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boekhorst F, Bogers H, Martens J. Renal pelvis rupture during pregnancy: diagnosing a confusing source of despair. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lo KL, Ng CF, Wong WS. Spontaneous rupture of the left renal collecting system during pregnancy. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:396-398. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Choi SK, Lee S, Kim S, Kim TG, Yoo KH, Min GE, Lee HL. A rare case of upper ureter rupture: ureteral perforation caused by urinary retention. Korean J Urol. 2012;53:131-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kalafatis P, Zougkas K, Petas A. Primary ureteroscopic treatment for obstructive ureteral stone-causing fornix rupture. Int J Urol. 2004;11:1058-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akpinar H, Kural AR, Tüfek I, Obek C, Demirkesen O, Solok V, Gürtug A. Spontaneous ureteral rupture: is immediate surgical intervention always necessary? J Endourol. 2002;16:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Henderickx MMEL, Brits T, De Baets K, Seghers M, Maes P, Trouet D, De Wachter S, De Win G. Renal papillary necrosis in patients with sickle cell disease: How to recognize this 'forgotten' diagnosis. J Pediatr Urol. 2017;13:250-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang HB, Yeh CL, Hsu KF. Spontaneous rupture renal angiomyolipoma with hemorrhagic shock. Intern Med. 2009;48:1111-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yu Y, Li J, Hou H. A rare case of spontaneous renal rupture caused by anca - associated vasculitides. Int Braz J Urol. 2018;44:1042-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Favi E, Iesari S, Cina A, Citterio F. Spontaneous renal allograft rupture complicated by urinary leakage: case report and review of the literature. BMC Urol. 2015;15:114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tarrass F, Benjelloun M, Medkouri G, Hachim K, Gharbi MB, Ramdani B. Spontaneous kidney rupture--an unusual complication of Wegener's granulomatosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang JQ, Fielding JR, Zou KH. Etiology of spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. J Urol. 2002;167:1593-1596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McDougal WS, Kursh ED, Persky L. Spontaneous rupture of the kidney with perirenal hematoma. J Urol. 1975;114:181-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Khan A, Mastenbrook J, Bauler L. Pain in the hip: Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage in an elderly patient on apixaban. Am J Emerg Med 2020; 38: 1046.e1-1046. e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen GH, Hsiao PJ, Chang YH, Chen CC, Wu HC, Yang CR, Chen KL, Chou EC, Chen WC, Chang CH. Spontaneous ureteral rupture and review of the literature. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:772-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gerboni GM, Capra G, Ferro S, Bellino C, Perego M, Zanet S, D'Angelo A, Gianella P. The use of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the detection of active renal hemorrhage in a dog with spontaneous kidney rupture resulting in hemoperitoneum. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 2015;25:751-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang T, Xue S, Wang ZM, Duan XM, Wang DX. Diagnostic value of ultrasound in the spontaneous rupture of renal angiomyolipoma during pregnancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3875-3880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Habib M. Arterial embolization for spontaneous rupture of renal cell carcinoma. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2011;22:1243-1245. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Hickling DR, Sun TT, Wu XR. Anatomy and Physiology of the Urinary Tract: Relation to Host Defense and Microbial Infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2015;3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Choe HS, Lee SJ, Yang SS, Hamasuna R, Yamamoto S, Cho YH, Matsumoto T; Committee for Development of the UAA-AAUS Guidelines for UTI and STI. Summary of the UAA-AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018;25:175-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bahadin J, Teo SS, Mathew S. Aetiology of community-acquired urinary tract infection and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of uropathogens isolated. Singapore Med J. 2011;52:415-420. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Gołębiewska JE, Krawczyk B, Wysocka M, Ewiak A, Komarnicka J, Bronk M, Rutkowski B, Dębska-Ślizień A. Host and pathogen factors in Klebsiella pneumoniae upper urinary tract infections in renal transplant patients. J Med Microbiol. 2019;68:382-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Huai W, Ma QB, Zheng JJ, Zhao Y, Zhai QR. Distribution and drug resistance of pathogenic bacteria in emergency patients. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3175-3184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |