Published online Apr 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2569

Peer-review started: December 25, 2020

First decision: January 10, 2021

Revised: January 23, 2021

Accepted: February 8, 2021

Article in press: February 8, 2021

Published online: April 16, 2021

Processing time: 97 Days and 21.2 Hours

Nemaline myopathy (NM) is a rare type of congenital myopathy, with an incidence of 1:50000. Patients with NM often exhibit hypomyotonia and varying degrees of muscle weakness. Skeletal muscles are always affected by this disease, while myocardial involvement is uncommon. However, with improvements in genetic testing technology, it has been found that NM with a mutation in the myopalladin (MYPN) gene not only causes slow, progressive muscle weakness but also results in dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

A 3-year-old pre-school boy was admitted to our hospital with cough, edema, tachypnea, and an increased heart rate. The patient was clinically diagnosed with severe dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure, and subsequent gene examination confirmed the diagnosis of NM with a mutation in MYPN. Captopril, diuretics, low-dose digoxin, and dobutamine were administered. After 22 d of hospitalization, the patient was discharged due to the improvement of clinical symptoms. During the follow-up period, the patient died of refractory heart failure.

Decreased muscular tone and dilated cardiomyopathy are common features of MYPN-mutated NM. Heart transplantation may be a solution to this type of cardiomyopathy.

Core Tip: Nemaline myopathy (NM) is a rare kind of congenital myopathy, with an incidence of 1:50000. The pathological characteristic is accumulated “rod” shaped structures in the muscle biopsies observed by light or electron microscopy. NM patients often have hypomyotonia and different degrees of muscle weakness. Skeletal muscles are always involved in this disease, while myocardial involvement is uncommon. However, it has been recognized that NM with mutation in myopalladin (MYPN) gene also results in dilated cardiomyopathy or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Here, we report the case of a 3-year-old boy with NM who was admitted with dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure followed by genetic confirmation of NM with an MYPN mutation.

- Citation: Wang Q, Hu F. Nemaline myopathy with dilated cardiomyopathy and severe heart failure: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(11): 2569-2575

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i11/2569.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2569

Nemaline myopathy (NM) is a rare type of congenital myopathy, with an incidence of 1:50000[1]. A distinct pathological characteristic of NM is the accumulation of “rod” shaped structures observed by light or electron microscopy in muscle biopsies[2]. Patients with NM often have hypomyotonia and varying degrees of muscle weakness. Skeletal muscles are always affected by this disease, while myocardial involvement is uncommon. However, with improvements in genetic testing technology, it has been recognized that NM with a mutation in the myopalladin (MYPN) gene not only causes slow, progressive muscle weakness but also results in dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy[3] .

Here, we report the case of a 3-year-old boy with NM who was admitted with dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure followed by the genetic confirmation of NM with an MYPN mutation. The ethics committee of the West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

A 3-year-old boy was referred to our hospital with cough, edema, tachypnea, and tachycardia.

One week before admission, the patient began to exhibit a paroxysm of coughing with phlegm, accompanied with fatigue and plummeting level of physical activity. Soon afterwards, he exhibited edema all over the body, particularly on the face and both lower limbs. Half a day before admission, the patient developed tachypnea and tachycardia.

It is worth noting that the patient had a history of delayed physical growth development. He only learned to sit when he was 10 mo old, and he still could not crawl or stand at 1 year of age. He was sent to a hospital and diagnosed with growth retardation. Doctors guided the boy in a rehabilitation training program for 1 year, after which he appeared to walk and run with no significant difference compared with his peers. However, the parents found that his muscle tension was low, and that he fell over easily. In addition, the patient had strephenopodia after birth, which improved after the use of orthotics.

The family history was unremarkable.

When the patient was admitted to our hospital, he had symmetrical edema in the face and lower extremities. The pulmonary respiratory sounds were rough with a few coarse rales. There was no protuberance in the precordial region. The apical impulse of the heart was diffused. Heart amplification was identified, and the apical beat was at the sixth intercostal space, 4.5 cm outside the middle line of the left clavicle. Neither thrill nor pericardium friction was found. The heart rhythm was regular with a gallop rhythm and low cardiac sound. The abdomen was supple with the liver 4 cm below the costal margin and 6 cm below the xiphoid, with the spleen impalpable. Moreover, the boy had an elongated face, inhibited facial expressions, a high palate arch (Figure 1), clawfoot, normal muscular strength, decreased muscular tone, and decreased bilateral knee reflexes. The Gower’s sign was positive, and the meningeal irritation sign was negative.

The serum cardiac troponin I level was 0.211 µg/L (normal < 0.034 µg/L). The level of brain natriuretic peptide reached up to 27500 pg/mL (normal < 215 pg/mL). The alanine aminotransferase level was 458 U/L (normal < 72 U/L), and aspartate aminotransferase level was 671 U/L (normal < 59 U/L). However, there was no significant increase in creatine kinase (99 U/L; normal < 170 U/L), creatine kinase myocardial band (2.29 μg/L; normal < 3.38 μg/L), and myoglobin (133.1 μg/L; normal < 121 μg/L).

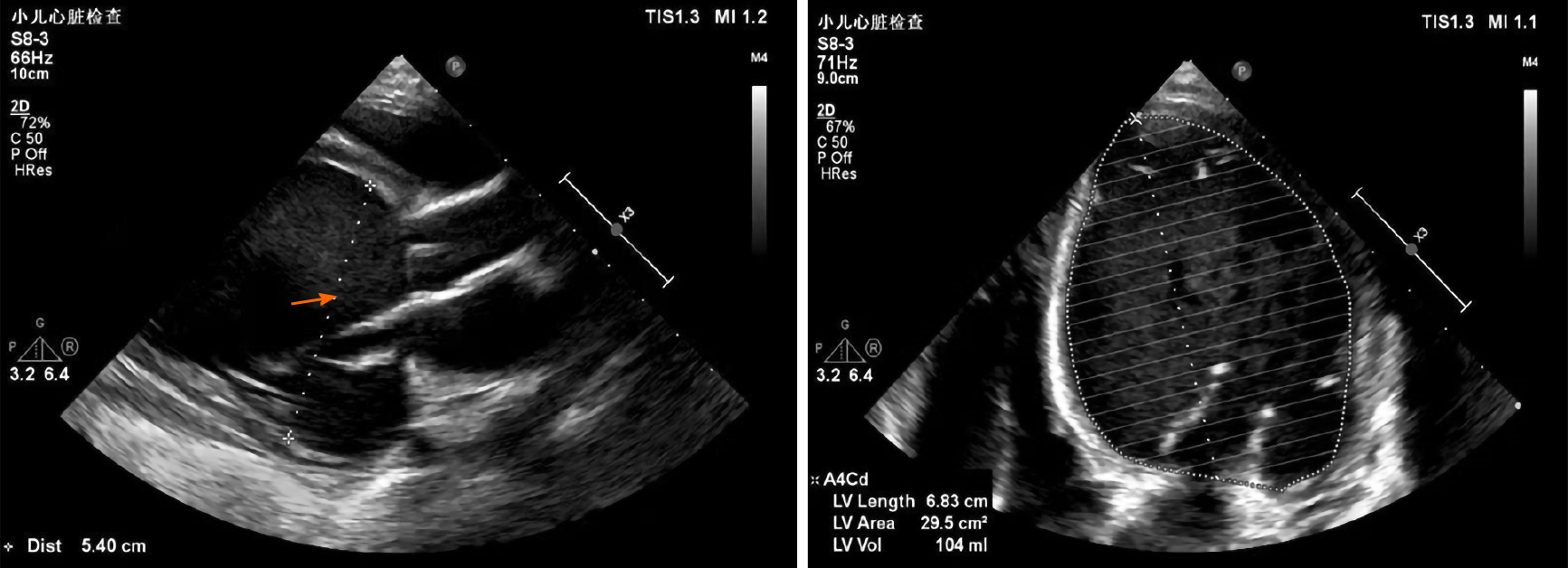

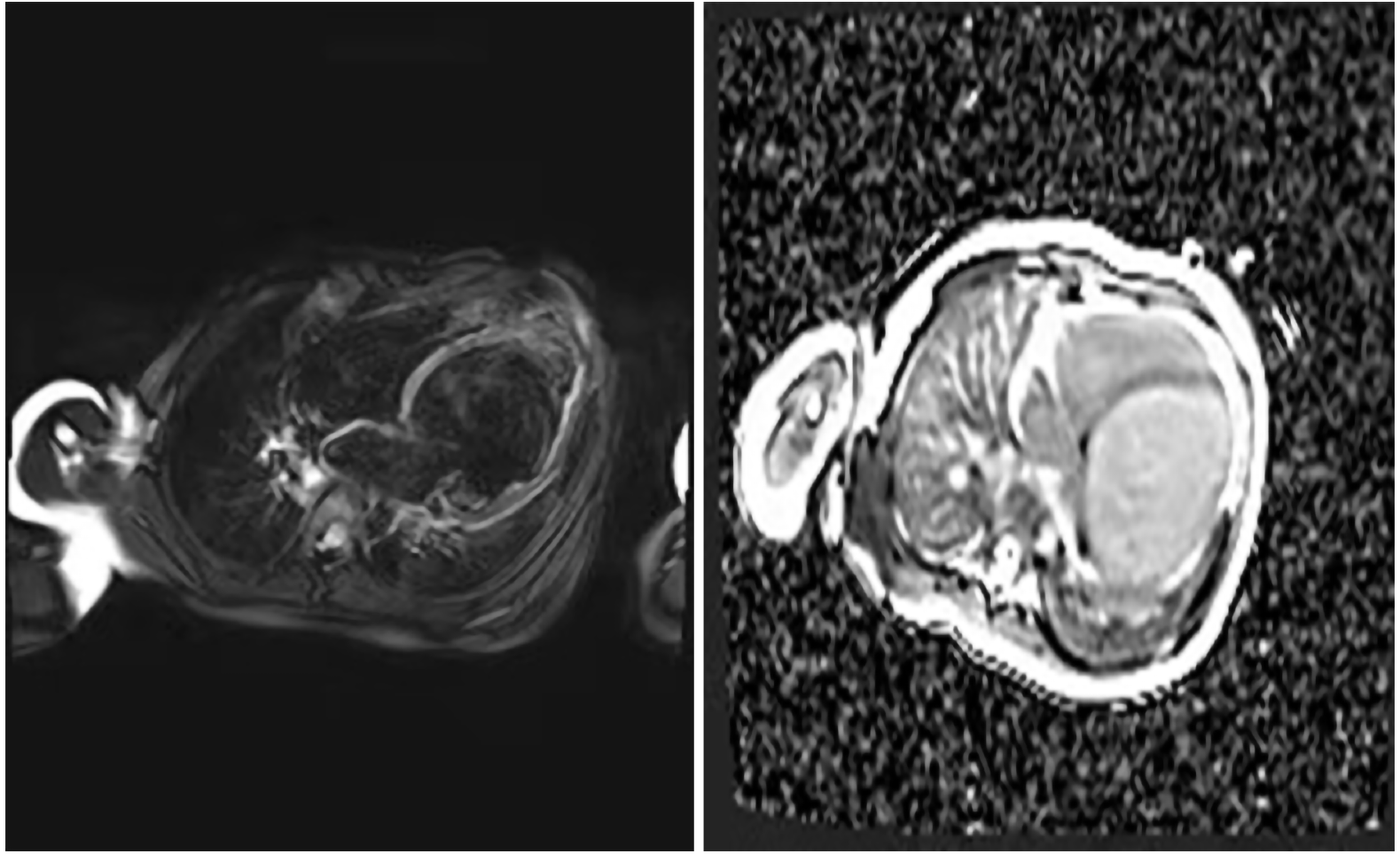

After one week in the hospital, Holter showed about 16.6% of ventricular premature beats (VPBs) of the total number of beats (Figure 2). Echocardiogram showed that the patient had enlarged, weakened left and right ventricles with decreased systolic function. The heart chamber sizes were as follows: Left atrium, 27 mm (normal < 18 mm); left ventricle, 58 mm (normal < 31 mm); right atrium, 40 mm (normal < 32 mm); right ventricle, 22 mm (normal < 11 mm). The ejection fraction was 18%, and the fraction of shortening was 8%. The systolic excursion of the tricuspid annular plane was 13 mm (Figure 3). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed enlarged ventricles, reduced systolic function, and focal delayed enhancement (Figure 4).

Based on the above findings, NM was suspected.

Initially, we thought that the condition in question might be myocarditis or idiopathic cardiomyopathy. The patient received spironolactone (2 mg/kg), hydrochlorothiazide (2 mg/kg), captopril (1 mg/kg), and digoxin (6 μg/kg). In addition, intravenous methylprednisolone was administered for 3 d followed by oral prednisone for 4 d. The degree of heart failure appeared to be very severe, so dobutamine (6 μg/kg) was also administered on the day of admission. The edema and cough improved, with the disappearance of rales after 1 wk of treatment, and we stopped using dobutamine (Table 1).

| Symptoms | Signs | Drug administration | ||||||

| Edema | Cough | Tachypnea | Tachycardia | Rale | Gallop rhythm | Hepatomegaly | ||

| Day 1 | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | 4 cm below costal margin | Spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, captopril, digoxin, dobutamine, methylprednisolone |

| Day 4 | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | 4 cm below costal margin | Spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, captopril, digoxin, dobutamine, prednisolone |

| Day 8 | - | - | ++ | ++ | - | + | 4 cm below costal margin | Spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, captopril, digoxin |

| Day 18 | - | - | + | + | - | - | 3 cm below costal margin | Spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, captopril, digoxin |

| Day 22 | - | - | + | + | - | - | 3 cm below costal margin | Spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, captopril, digoxin |

We continued using spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, captopril, digoxin, and dobutamine (we stopped using dobutamine when the patient was in stable condition). After 22 d of treatment, the edema completely regressed and the gallop rhythm disappeared. The patient still exhibited sinus tachycardia with a reduced VPB of 8.9%. Echocardiography showed that the ejection fraction was 23% and the fraction of shortening was 11% after treatment.

The patient was discharged due to improvement in heart failure symptoms. He continued to be administered with spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, captopril, and digoxin at home. During the follow-up period, the patient suffered from repeated and worsened heart failure and was hospitalized. Ultimately, he died of uncontrollable heart failure 4 mo after the first admission.

NM is a sporadic, rare congenital myopathy[4] . Genetic mutations that cause skeletal muscle involvement lead to this disease. Clinical manifestations vary in different patients. NM was divided into six types by the European Commission for Neuromuscular Diseases[5]: (1) Severe congenital NM. Patients exhibit clinical symptoms at birth, with feeding difficulties, hypotonia, myasthenia, respiratory failure, and no independent activities. Most patients die at an early stage, usually no more than one year of age; (2) Typical form of NM. This type has the highest incidence. Children get sick at an early age, with obvious muscle weakness in the face, medulla oblongata, and respiratory system. Muscle strength possibly increases with age. The quality of life in most patients is not affected. Patients have normal intelligence and myocardial contractility; (3) Intermediate congenital NM. This form has an onset in early infancy, spontaneous respiratory movement may occur at birth, but in early childhood. Patients may develop an inability to breathe autonomously, and walk and stand independently. Muscle contractures may occur during early childhood. The clinical symptoms of this type of NM are congenital severe syndromes and congenital mild syndromes; (4) Mild, childhood-, or juvenile-onset NM. The clinical manifestations are similar to mild syndromes, except that the onset age is late childhood or adolescence; (5) Adult form of NM. The age of onset is 30 to 60 years, and this form is incredibly diverse, with vast differences in clinical manifestations and disease progression. Cases are sporadic and have no family history. The onset is acute or subacute, and the respiratory muscles are easily involved. The disease has a quick course, and most patients have a poor prognosis; and (6) Other forms of NM. These are rare types, presenting as cardiomyopathy, ophthalmoplegia, abnormal muscle weakness distribution, and internuclear rods.

The presence of rod-like bodies is a characteristic change observed in muscle biopsies, and there are many eosinophilic rod-like structures under the myofilm or in the myoplasm[6-8] . However, due to various limitations, muscle biopsies are not easy to perform. Besides, with the development of genetic testing, muscle biopsies are no longer the only gold standard. Our patient did not undergo a muscle biopsy due to severe heart failure and refusal from the parents.

So far, at least 13 gene mutations have been recognized to be associated with NM, including TPM3, NEB, ACTA1, TPM2, TNNT1, KBTBD13, CFL2, KLHL40, KLHL41, LMOD3, MYO18B, TNNT3, and MYPN[3]. MYPN is a sarcoma component. It is generally found in the sarcomere, cardiac muscle, and skeletal muscle nucleus. The central regions and C-terminus of MYPN can bind to both α-actinin and nebulin in the skeletal muscle or nebulette in the cardiac muscle at the Z-line[9] . On the other hand, its N-terminal region binds to cardiac ankyrin repeat protein[10] . In an animal model, MYPN has been shown to potentially promote muscle growth[11]. Patients with MYPN mutations show manifestations of myopathy and dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy[12,13] .

The patient in question had normal intelligence, but his motor developmental milestones were delayed after birth. In addition, the facial and skeletal characteristics, including an elongated face, high palate arch, and clawfoot, are typical signs of NM[14,15]. Decreased muscular tone, a positive Gower’s sign, and dilated car-diomyopathy are common features of MYPN-mutated NM. The typical clinical manifestations and genetic tests supported the diagnosis. Unfortunately, the heart failure was too severe to be controlled by drugs. β-blockers are another treatment option for cardiomyopathy but the patient had such poor heart function that we did not use it after careful evaluation of the risk. Heart transplantation may be a solution to this type of cardiomyopathy.

In some cases, life-threatening cardiomyopathy with severe heart failure is a manifestation of inherited myopathy. When diagnosing cardiomyopathy, the development of striated muscles should be detected.

We thank all of the participants in this case report and people involved in diagnosis. We thank the Sichuan Province Science and Technology Support Program of China. We also thank the parents of the patient, who were always cooperative with our doctors.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dziewięcka E S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | de Winter JM, Ottenheijm CAC. Sarcomere Dysfunction in Nemaline Myopathy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2017;4:99-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cassandrini D, Trovato R, Rubegni A, Lenzi S, Fiorillo C, Baldacci J, Minetti C, Astrea G, Bruno C, Santorelli FM; Italian Network on Congenital Myopathies. Congenital myopathies: clinical phenotypes and new diagnostic tools. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43:101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sewry CA, Laitila JM, Wallgren-Pettersson C. Nemaline myopathies: a current view. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2019;40:111-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yeşilbaş O, Şevketoğlu E, Kıhtır HS, Ersoy M, Petmezci MT, Akkuş CH, Şahin Ö, Ceylaner S. A rare structural myopathy: Nemaline myopathy. Turk Pediatri Ars. 2019;54:49-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wallgren-Pettersson C, Laing NG. Report of the 70th ENMC International Workshop: nemaline myopathy, 11-13 June 1999, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord. 2000;10:299-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schnitzler LJ, Schreckenbach T, Nadaj-Pakleza A, Stenzel W, Rushing EJ, Van Damme P, Ferbert A, Petri S, Hartmann C, Bornemann A, Meisel A, Petersen JA, Tousseyn T, Thal DR, Reimann J, De Jonghe P, Martin JJ, Van den Bergh PY, Schulz JB, Weis J, Claeys KG. Sporadic late-onset nemaline myopathy: clinico-pathological characteristics and review of 76 cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | D'Amico A, Fattori F, Fiorillo C, Paglietti MG, Testa MBC, Verardo M, Catteruccia M, Bruno C, Bertini E. 'Amish Nemaline Myopathy' in 2 Italian siblings harbouring a novel homozygous mutation in Troponin-I gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29:766-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sztal TE, Zhao M, Williams C, Oorschot V, Parslow AC, Giousoh A, Yuen M, Hall TE, Costin A, Ramm G, Bird PI, Busch-Nentwich EM, Stemple DL, Currie PD, Cooper ST, Laing NG, Nowak KJ, Bryson-Richardson RJ. Zebrafish models for nemaline myopathy reveal a spectrum of nemaline bodies contributing to reduced muscle function. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:389-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Miyatake S, Mitsuhashi S, Hayashi YK, Purevjav E, Nishikawa A, Koshimizu E, Suzuki M, Yatabe K, Tanaka Y, Ogata K, Kuru S, Shiina M, Tsurusaki Y, Nakashima M, Mizuguchi T, Miyake N, Saitsu H, Ogata K, Kawai M, Towbin J, Nonaka I, Nishino I, Matsumoto N. Biallelic Mutations in MYPN, Encoding Myopalladin, Are Associated with Childhood-Onset, Slowly Progressive Nemaline Myopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100:169-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bang ML, Mudry RE, McElhinny AS, Trombitás K, Geach AJ, Yamasaki R, Sorimachi H, Granzier H, Gregorio CC, Labeit S. Myopalladin, a novel 145-kilodalton sarcomeric protein with multiple roles in Z-disc and I-band protein assemblies. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:413-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Merlini L, Sabatelli P, Antoniel M, Carinci V, Niro F, Monetti G, Torella A, Giugliano T, Faldini C, Nigro V. Congenital myopathy with hanging big toe due to homozygous myopalladin (MYPN) mutation. Skelet Muscle. 2019;9:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhao Y, Feng Y, Zhang YM, Ding XX, Song YZ, Zhang AM, Liu L, Zhang H, Ding JH, Xia XS. Targeted next-generation sequencing of candidate genes reveals novel mutations in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Med. 2015;36:1479-1486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen Y, Barajas-Martinez H, Zhu D, Wang X, Chen C, Zhuang R, Shi J, Wu X, Tao Y, Jin W, Wang X, Hu D. Erratum to: Novel trigenic CACNA1C/DES/MYPN mutations in a family of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with early repolarization and short QT syndrome. J Transl Med. 2017;15:101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xue Y, Magoulas PL, Wirthlin JO, Buchanan EP. Craniofacial Manifestations in Severe Nemaline Myopathy. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28:e258-e260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yeung KS, Yu FNY, Fung CW, Wong S, Lee HHC, Fung STH, Fung GPG, Leung KY, Chung WH, Lee YT, Ng VKS, Yu MHC, Fung JLF, Tsang MHY, Chan KYK, Chan SHS, Kan ASY, Chung BHY. The KLHL40 c.1516A>C is a Chinese-specific founder mutation causing nemaline myopathy 8: Report of six patients with pre- and postnatal phenotypes. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8:e1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |