Published online Apr 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2533

Peer-review started: September 8, 2020

First decision: December 8, 2020

Revised: December 16, 2020

Accepted: February 11, 2021

Article in press: February 11, 2021

Published online: April 16, 2021

Processing time: 199 Days and 21.9 Hours

Primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma is a rare histologic subtype of epithelial ovarian carcinoma and exhibits considerable morphologic overlap with secondary tumour. It is hard to differentiate primary from metastatic ovarian mucinous carcinoma by morphological and immunohistochemical features. Because of the histologic similarity between primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma and metastatic gastrointestinal carcinoma, it has been hypothesized that ovarian mucinous carcinomas might respond better to non-gynecologic regimens. However, the standard treatment of advanced ovarian mucinous carcinoma has not reached a consensus.

A 56-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with repeated pain attacks in the right lower quadrant abdomen, accompanied by diarrhoea, anorexia, and weight loss for about 3 mo. The patient initially misdiagnosed as having gastrointestinal carcinoma because of similar pathological features. Based on the physical examination, tumour markers, imaging tests, and genetic tests, the patient was clinically diagnosed with ovary mucinous adenocarcinoma. Whether gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy or gynecologic chemotherapy was a favourable choice for patients with advanced ovarian mucinous cancer had not been determined. The patient received a chemotherapy regimen based on the histologic characteristics rather than the tumour origin. The patient received nine cycles of FOLFOX and bevacizumab. This was followed by seven cycles of bevacizumab maintenance therapy for 9 mo. Satisfactory therapeutic efficacy was achieved.

The genetic analysis might be used in the differential diagnosis of primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma and non-gynecologic mucinous carcinoma. Moreover, primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma patients could benefit from gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy.

Core Tip: Primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma is a rare histologic subtype of epithelial ovarian carcinoma and exhibits considerable morphologic overlap with secondary tumour. Because of the histologic similarity between primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma and metastatic gastrointestinal carcinoma, it has been hypothesized that ovarian mucinous carcinomas might respond better to non-gynecologic regimens. Here, we report an initially misdiagnosed case of primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma by considering clinical characteristics, imaging, and genetic tests. The patient received a chemotherapy regimen based on the histologic characteristics rather than the tumour origin. This achieved satisfactory therapeutic efficacy.

- Citation: Wang Q, Niu XY, Feng H, Wu J, Gao W, Zhang ZX, Zou YW, Zhang BY, Wang HJ. Gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy prolongs survival in an atypical primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(11): 2533-2541

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i11/2533.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2533

Primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma is a rare histologic subtype of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), only accounting for 2% of new EOC cases[1]. Unlike other histologic types, it is presented with a low histologic grade and usually diagnosed at an early stage. Nevertheless, advanced stage cases are often associated with a poor prognosis and chemotherapy resistance[2-5]. Because the morphological features of primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma can be mimicked by gastrointestinal metastases, pathologic diagnosis can particularly be challenging[6,7]. Histopathologic evaluation of hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemical analysis offers few markers with limited value in the differential diagnosis. Because of the histologic similarity between primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma and metastatic gastrointestinal carcinoma, it has been hypothesized that ovarian mucinous carcinomas might respond better to non-gynecologic regimens[8]. However, the standard chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of advanced ovarian mucinous carcinoma remains unestablished. Herein, we report an initially misdiagnosed case of primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma by considering clinical characteristics, imaging, and genetic tests. The patient received a chemotherapy regimen based on the histologic characteristics rather than the tumour origin. This achieved satisfactory therapeutic efficacy.

A 56-year-old postmenopausal woman visited our hospital with lower abdominal pain.

The patient presented with repeated pain attacks in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, accompanied by diarrhea, anorexia, and weight loss for approximately 3 mo. She took diclofenac sodium mucilage 1-2 times daily to relieve the pain, with a pain score ranging from 3 to 4 points.

The patient had hypertension for 3 years. The blood pressure ranged from 120-140/80-100 mmHg after taking nifedipine controlled-release tablets and enalapril. She received laparoscopic cholecystectomy, resection of lateral lobe of the left liver, and choledocholithotomy with exploration because of cholelithiasis. Histologically, there was a large range of related inflammatory epithelial changes including fibrosis, mononuclear infiltrate, and thickening of the muscular layer.

Menarche occurred at 13 years of age, and menstrual cycles were regular, with bleeding typically occurring every 30 d and lasting for 5-6 d. She married at the age of 25 years and had a son and two daughters. The patient had an occasional drink but did not smoke tobacco or use illicit drugs. Her father had died of liver cancer associated with hepatitis B virus, her mother had died of cerebral hemorrhage, one brother had died of cholangiocarcinoma, and another had died of gastric cancer. Her sister and younger brother were healthy.

On examination, there were several hard and painless masses at the left-sided cervical and supraclavicular regions. The largest mass (measuring 2 cm × 3 cm) was located at the lower neck (level IV). There was tenderness in the right lower quadrant. The liver and spleen were impalpable.

The baseline results of laboratory tests and tumor markers are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

| Variable | On presentation | Reference range |

| Blood routine examination | ||

| White blood cell count | 6.69 × 109/L | 3.5-9.5 × 109/L |

| Neutrophils | 5.33 × 109/L | 1.8-6.3 × 109/L |

| Lymphocytes | 1.02 × 109/L | 1.1-3.2 × 109/L |

| Monocytes | 0.31 × 109/L | 0.1-0.6 × 109/L |

| Eosinophils | 0.01 × 109/L | 0.02-0.52 × 109/L |

| Basophils | 0.02 × 109/L | 0-0.06 × 109/L |

| Hemoglobin | 124 g/L | 115-150 g/L |

| Platelet | 161 × 109/L | 125-350 × 109/L |

| Sodium | 147 mmol/L | 137-147 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 2.9 mmol/L | 3.5-5.3 mmol/L |

| Chloride | 105 mmol/L | 99-110 mmol/L |

| Calcium | 2.62 mmol/L | 2.11-2.52 mmol/L |

| Albumin | 44.9 g/L | 20-55 g/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 23 U/L | 13-35 U/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 17 U/L | 7-40 U/L |

| Bilirubin | 18.91 μmol/L | 3-22 μmol/L |

| Creatinine | 81 μmol/L | 31-132 μmol/L |

| Urea nitrogen | 3.12 mmol/L | 2.6-7.5 mmol/L |

| Cystatin c | 0.88 mg/L | 0.10-0.45 mg/L |

| Variable | Reference range | First visit | Second hospitalisation | Third hospitalisation | Forth hospitalisation | Last dose of chemotherapy |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0-3.4 | 44.04 | 28.69 | 17.18 | 5.67 | 3.21 |

| CA242 (IU/mL) | 0-15 | 18.08 | 14.45 | 10.81 | 7.85 | 8.52 |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 0-39 | 100.8 | 60.81 | 33.83 | 18.39 | 16.70 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 0-7.02 | 9.03 | 8.09 | 7.16 | 6.15 | 6.75 |

| CA15-3 (U/mL) | 0-25 | 30.37 | 22.58 | 20.13 | 15.84 | 14.70 |

| CA125 (U/mL) | 0-35 | 137.4 | 40.68 | 21.11 | 11.66 | 12.10 |

| HE4 (pmol/L) | < 140 | 105.7 | 72.3 | 70.1 | 64.4 | 50.7 |

The total abdominal and pelvic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan at a local hospital indicated enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes measuring 1 cm in diameter and a small amount of pelvic free fluid. There were no obvious occupying lesions in the uterus, bilateral adnexa, or iliac blood vessel area.

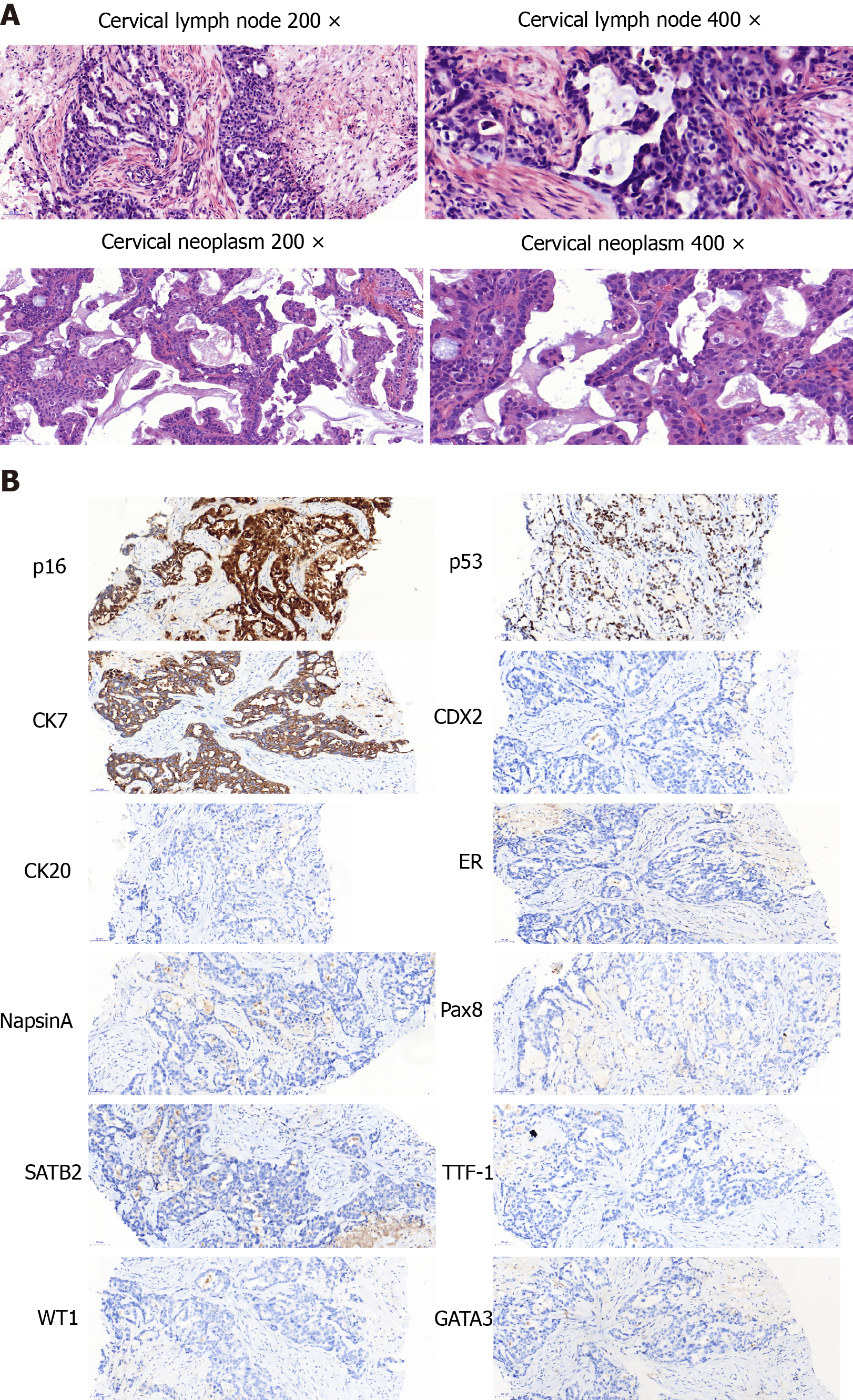

The aspiration biopsy of the cervical lymph nodes under ultrasound guidance showed lowly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma. The tumour cells were mainly arranged in an irregular adenoid, cribriform, or strip-shaped pattern with moderate to severe atypia. The nucleus was round or ovoid-shaped and centrally located in the cells. A moderate amount of extracellular mucus was found. The tumour cells were embedded in the collagenized desmoplastic stroma with focal necrosis. Tumour cells expressed CK7, p53, and p16 but not CK20, TTF-1, GATA3, CDX-2, Pax-8, ER, SATB2, NapsinA, and WT-1 (Figure 1). The pathologists suspected metastases from the digestive and biliary tract. They reviewed the patient’s pathological specimen from the hepatobiliary operation and found no precancerous lesions or invasive carcinoma. Gastroscopy and colonoscopy also showed no abnormal mass.

The patient refused further medical examination and resorted to traditional Chinese medicine at her discretion for 2 mo. After aggravated symptoms, she visited our hospital again for further evaluation and a general checkup was performed. Gynaecological examination revealed a smooth cervix and a neoplasm of about 0.5 cm in size. The rest of the examination was as previously reported.

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) showed multiple hypermetabolic foci of the neck, supraclavicular fossa, axilla, pectoralis major deep surface, retroperitoneal area, right adnexal mass, and osteolytic bone destruction of the right 8th rib.

The patient refused the diagnostic operation and CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of the right adnexal occupying lesions. Therefore, the pathological diagnosis was not obtained. However, the biopsy of the cervical neoplasm indicated poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. The pathologists compared the morphological characteristics between the tumour cells of the cervical lymph nodes and cervical neoplasm and concluded that the two metastases were from the same origin. The morphology of the tumour cells in cervical biopsy was similar to some extent to that of the lymph node in the neck but it was much richer in the papillary arrangement, especially the extracellular mucus, and was diagnosed as mucinous adenocarcinoma. The intracellular mucus was more visible and the columnar mucinous epithelium was more abundant than those in the neck lesion were. After combining the medical history and immunohistochemical results, the biliary tract and the ovary were the two most likely sources.

The genetic tests of the metastatic lymph node, cervical neoplasm, and blood revealed a BRCA2 exon 20 truncating mutation and epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM) exon 7 frameshift mutation (Table 3). Based on the physical examination, tumour markers, imaging tests, and genetic tests, the patient was clinically diagnosed with ovary mucinous adenocarcinoma.

| Gene | Variation | Mutation | Cervical lymph node | Cervical neoplasm | Peripheral Blood |

| Tumor-specific mutation | |||||

| CCNE1 | Gene amplification | - | 3.1-fold | - | |

| DLL3 | Gene amplification | - | 3.2-fold | - | |

| KRAS | Gene amplification | 5.2-fold | 9.8-fold | - | |

| PTK2 | Gene amplification | - | 2.2-fold | - | |

| RB1 | Splice site mutation | c.1421+29_1498+69del | 8.5% | 52.0% | 0.4% |

| STK11 | Single copy deletion | - | Single copy deletion | - | |

| VHL | Single copy deletion | - | Single copy deletion | - | |

| DDR2 | Truncation mutation | c.1646C>G(p.S549*) | 10.4% | 20.8% | 0.8% |

| EPHA3 | Missense mutation | c.2515G>A(p.E839K) | - | 1.1% | - |

| ETV6 | Missense mutation | c.369G>C(p.Q123H) | 14.0% | 23.5% | 0.9% |

| GNAS | Missense mutation | c.1984G>A(p.E662K) | 13.4% | - | 0.6% |

| TAP1 | Missense mutation | c.149C>T(p.P50L) | 2.0% | - | - |

| TP53 | Splice site mutation | c.376-1G>A | 18.2% | 69.9% | 0.8% |

| TP53 | Single copy deletion | - | - | Single copy deletion | - |

| Germline mutation | Mutation | ||||

| BRCA2 | Truncation mutation | c.8629G>T(p.E2877*) | |||

| EPCAM | Frameshift mutation | c.843delT(p.G282Efs*21) | |||

Based on the physical examination, tumor markers, imaging tests, and genetic tests, the patient was clinically diagnosed with ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma.

The patient received nine cycles of FOLFOX and bevacizumab (oxaliplatin: 100 mg/m2, calcium levofolinate, 5-fluorouracil bolus 400 mg/m2, 5-fluorouracil civ46h, 2400-3000 mg/m2, bevacizumab 5 mg/kg, q2w). This was followed by seven cycles of bevacizumab maintenance therapy for 9 mo.

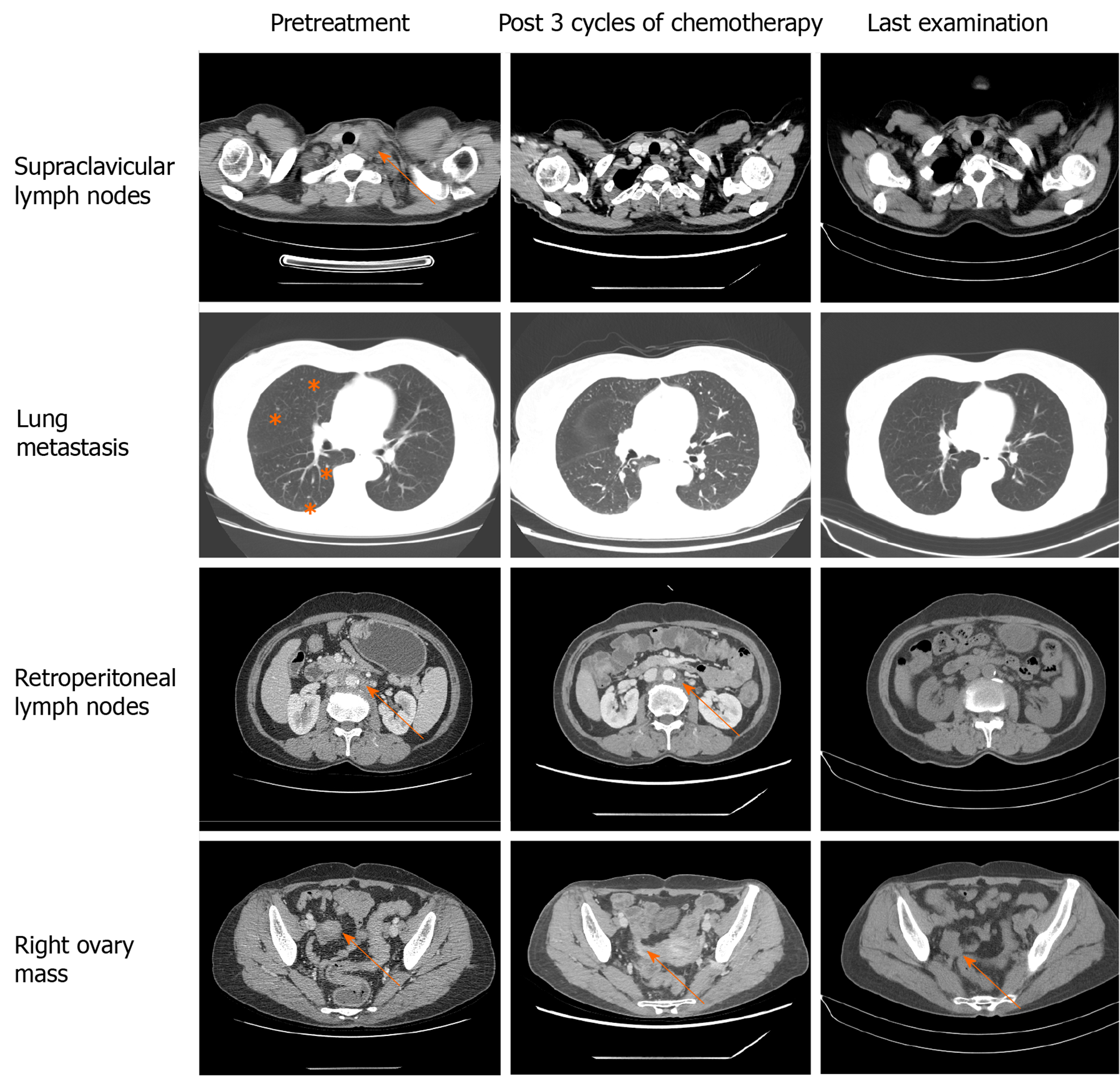

Imaging tests were performed after every three cycles of chemotherapy to evaluate the therapeutic effect. CT indicated continuous shrinkage of the lymphatic metastases without evidence of new metastatic disease (Figure 2). Before the treatment, evaluation of the tumor markers showed noticeable levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), CA125, and CA242 (Table 2). After four cycles of chemotherapy, all the tumor markers decreased to normal ranges.

Primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma accounts for 1%-2% of all primary ovarian carcinomas[1]. Unlike other histologic types, mucinous carcinomas usually have a low histologic grade, present at an early stage, and are associated with a favourable outcome. However, primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma should be distinguished from metastatic tumours to the ovary. Gastrointestinal, breast, and endometrial origins are the most common, and all exhibit considerable morphologic overlap. Histopathologic evaluation of the HE staining and immunohistochemical analysis is usually problematic in identifying and distinguishing primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma and metastatic carcinoma[7].

In the present case, it was difficult to achieve a precise diagnosis. First, both the gastrointestinal and ovarian tumour markers were elevated. Serum CEA, CA19-9, and CA242 levels are most frequently elevated in patients with pancreatic and gastrointestinal tract tumours. Serum CA125 is a tumour marker derived from tethered mucin, MUC16, and is usually associated with serous and endometrioid tumours.

Second, the right adnexal occupying lesion was relatively small. Unilateral ovarian tumours of more than 10 cm in the greatest dimension are most likely to be ovarian in origin, whereas bilateral, smaller ovarian masses are more likely to be metastatic[9]. The characteristics of metastases are also inconsistent with primary ovarian cancer. The metastatic spread of ovarian cancer is characterized by ascites and widespread peritoneal implantation. However, our case mainly showed multiple salutatory lymph node metastases.

Finally, although the immunohistochemical profile was consistent with a typical profile of ovarian mucinous carcinoma[10], it was hard to differentiate metastatic carcinoma and ovarian cancer by the morphological features. After combining the medical history and immunohistochemical results, the biliary tract and the ovary were the two most likely sources. Because CK7, p16, and p53 may be positive in both potential sources, immunohistochemical indicators are not reliable. Ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma is rare and often gastrointestinal-epithelium like. In our case, the morphologies in both lesions lacked the typical characteristics of gastrointestinal epithelium features such as nuclear spindling or goblet-shaped like epithelial cells. Stromal sclerosis is one of the characteristics of biliary epithelial carcinoma. The lesion in the neck lymph node was very similar to stromal sclerosis not only in cellular morphology but also in heavy stroma fibrosis.

The most expedient way to establish the diagnosis would be to perform diagnostic laparotomy with an intraoperative frozen section examination. However, the patient refused the diagnostic operation and CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of the right adnexal occupying lesions. The patient was diagnosed with ovarian mucinous carcinoma based on the following reasons. Although the tumour-marker profile favored the diagnosis of biliary and gastrointestinal carcinoma, the PET-CT and gastroendoscopy showed no abnormal mass. Next, genetic tests revealed BRCA2 exon 20 truncating mutation (p.E2877), which has been identified as the mutation for hereditary breast, ovarian, and other related cancers in the ClinVar website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/). The relationship between EPCAM mutation and carcinogenesis has not been previously reported in the literature. Based on the Cancer Genome Atlas, mutations of this gene are common in melanoma, ovarian cancer, leiomyosarcoma, and cholangiocarcinoma.

Because of the histologic similarity between primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma and metastatic gastrointestinal carcinoma, it has been hypothesized that ovarian mucinous carcinomas might respond better to non-gynecologic regimens. GOG-241, a randomized controlled trial, was designed to compare the gastrointestinal regimen to standard gynecologic regimen among ovarian mucinous carcinoma patients[11]. However, the trial was closed prematurely because of low recruitment rates. Nonetheless, more than half of the enrolled patients so far were diagnosed with non-gynecologic mucinous carcinoma after the central review by pathologists. Kurnit et al[12] conducted a retrospective study to estimate whether gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy was associated with improved survival compared with standard gynecologic regimens for ovarian mucinous carcinoma patients. They found that gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab improved survival in patients with ovarian mucinous carcinoma requiring adjuvant therapy. However, the vast majority of patients were at an early stage and receiving surgery. Whether gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy or gynecologic chemotherapy is a favourable choice for patients with advanced ovarian mucinous cancer has not been determined. Our patient received FOLFOX + bevacizumab as the first-line chemotherapy regimen. Interestingly, partial remission was achieved after three cycles of chemotherapy, which was maintained for approximately 1 year.

We report an initially misdiagnosed case of primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma by considering clinical characteristics, imaging, and genetic tests. The patient received chemotherapy regimen based on the histologic characteristics rather than the tumour origin, achieving satisfactory therapeutic efficacy. However, further studies should focus on genetic analysis in the differential diagnosis of primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma and non-gynecologic mucinous carcinoma. Because of the rarity of this tumour, there are no standard criteria for the guidelines for treatment. In the future, standard treatments should be explored through randomized controlled trial or retrospective studies.

Genetic analysis might be used in the differential diagnosis of primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma and non-gynecologic mucinous carcinoma. Moreover, primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma patients could benefit from gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cihan YB, Neri V S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Zaino RJ, Brady MF, Lele SM, Michael H, Greer B, Bookman MA. Advanced stage mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary is both rare and highly lethal: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2011;117:554-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Karabuk E, Kose MF, Hizli D, Taşkin S, Karadağ B, Turan T, Boran N, Ozfuttu A, Ortaç UF. Comparison of advanced stage mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer and serous epithelial ovarian cancer with regard to chemosensitivity and survival outcome: a matched case-control study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2013;24:160-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chung YS, Park SY, Lee JY, Park JY, Lee JW, Kim HS, Suh DS, Kim YH, Lee JM, Kim M, Choi MC, Shim SH, Lee KH, Song T, Hong JH, Lee WM, Lee B, Lee IH. Outcomes of non-high grade serous carcinoma after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced-stage ovarian cancer: a Korean gynecologic oncology group study (OV 1708). BMC Cancer. 2019;19:341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Simons M, Ezendam N, Bulten J, Nagtegaal I, Massuger L. Survival of Patients With Mucinous Ovarian Carcinoma and Ovarian Metastases: A Population-Based Cancer Registry Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:1208-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Firat Cuylan Z, Karabuk E, Oz M, Turan AT, Meydanli MM, Taskin S, Sari ME, Sahin H, Ulukent SC, Akbayir O, Gungorduk K, Gungor T, Kose MF, Ayhan A. Comparison of stage III mucinous and serous ovarian cancer: a case-control study. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Riopel MA, Ronnett BM, Kurman RJ. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria and behavior of ovarian intestinal-type mucinous tumors: atypical proliferative (borderline) tumors and intraepithelial, microinvasive, invasive, and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:617-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Köbel M, Rahimi K, Rambau PF, Naugler C, Le Page C, Meunier L, de Ladurantaye M, Lee S, Leung S, Goode EL, Ramus SJ, Carlson JW, Li X, Ewanowich CA, Kelemen LE, Vanderhyden B, Provencher D, Huntsman D, Lee CH, Gilks CB, Mes Masson AM. An Immunohistochemical Algorithm for Ovarian Carcinoma Typing. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2016;35:430-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Frumovitz M, Schmeler KM, Malpica A, Sood AK, Gershenson DM. Unmasking the complexities of mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:491-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khunamornpong S, Suprasert P, Pojchamarnwiputh S, Na Chiangmai W, Settakorn J, Siriaunkgul S. Primary and metastatic mucinous adenocarcinomas of the ovary: Evaluation of the diagnostic approach using tumor size and laterality. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bassiouny D, Ismiil N, Dubé V, Han G, Cesari M, Lu FI, Slodkowska E, Parra-Herran C, Chiu HF, Naeim M, Li N, Khalifa M, Nofech-Mozes S. Comprehensive Clinicopathologic and Updated Immunohistochemical Characterization of Primary Ovarian Mucinous Carcinoma. Int J Surg Pathol. 2018;26:306-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gore M, Hackshaw A, Brady WE, Penson RT, Zaino R, McCluggage WG, Ganesan R, Wilkinson N, Perren T, Montes A, Summers J, Lord R, Dark G, Rustin G, Mackean M, Reed N, Kehoe S, Frumovitz M, Christensen H, Feeney A, Ledermann J, Gershenson DM. An international, phase III randomized trial in patients with mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer (mEOC/GOG 0241) with long-term follow-up: and experience of conducting a clinical trial in a rare gynecological tumor. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:541-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kurnit KC, Sinno AK, Fellman BM, Varghese A, Stone R, Sood AK, Gershenson DM, Schmeler KM, Malpica A, Fader AN, Frumovitz M. Effects of Gastrointestinal-Type Chemotherapy in Women With Ovarian Mucinous Carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:1253-1259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |