Published online Apr 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2469

Peer-review started: December 14, 2020

First decision: December 31, 2020

Revised: January 8, 2021

Accepted: February 1, 2021

Article in press: February 1, 2021

Published online: April 16, 2021

Processing time: 109 Days and 10.7 Hours

Gambling disorder is characterized by excessive and recurrent gambling and can have serious negative social consequences. Although several psychotherapeutic and pharmacological approaches have been used to treat gambling disorder, new treatment strategies are needed. Growing evidence suggests that dopamine D3 receptor plays a specific role in the brain reward system.

To investigate if blonanserin, a dopamine D3 receptor antagonist, would be effective in reducing gambling impulses in patients with gambling disorder.

We developed a study protocol to measure the efficacy and safety of blonanserin as a potential drug for gambling disorder, in which up to 12 mg/d of blonanserin was prescribed for 8 wk.

A 37-year-old female patient with gambling disorder, intellectual disability, and other physical diseases participated in the pilot study. The case showed improvement of gambling symptoms without any psychotherapy. However, blonanserin was discontinued owing to excessive saliva production.

This case suggests that blonanserin is potentially an effective treatment for patients with gambling disorder who resist standard therapies, but it also carries a risk of adverse effects. Further studies are needed to confirm the findings.

Core Tip: We developed a study protocol to examine the effect and safety of blonanserin on gambling disorder. A case was introduced in the study, to bring a promising outcome, but treatment was discontinued due to extrapyramidal adverse effects. A safer usage should be established.

- Citation: Shiina A, Hasegawa T, Iyo M. Possible effect of blonanserin on gambling disorder: A clinical study protocol and a case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(11): 2469-2477

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i11/2469.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i11.2469

Gambling disorder, or pathological gambling, is a mental condition characterized by recurrent maladaptive gambling behavior and difficulty in controlling gambling, despite the realization that the behavior is damaging [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)]. Gambling disorder has severe negative effects on social functioning[1]. According to the British Gambling Prevalence Survey, the United Kingdom prevalence rate is 0.9%, and this number has been slowly increasing each year[2]. In Japan, there are no official gambling disorder statistics because gambling is legally restricted, except for some officially recognized activities (e.g., horse races). However, many people play pachinko. Despite this restriction, an interim report from a national survey conducted in 2017 estimated the lifetime prevalence of gambling disorder in Japan to be 3.6% (data not published).

The pathophysiology of gambling disorder is still unclear. The behavior was previously termed “compulsive gambling” in reference to its obsessive–compulsive characteristics. However, it was moved to the ‘impulse control disorders’ category in the DSM-5 and was categorized as an addiction disorder in the DSM-5. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) describes gambling disorder as a form of behavior and categorizes it as a habit and impulse disorder. Cognitive distortion regarding the chance of winning games, a craving for gambling in risky situations, and a history of operant conditioning through intermittent reinforcement from winning games are frequently observed in patients with gambling disorder. However, the assumption that gambling disorder has a biological basis is controversial. Multiple neurotransmitter systems, such as the serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, opioid, and glutamate systems, have been implicated in gambling disorder[3,4]. Dopaminergic abnormalities seem to lead to excessive gambling through hyperactivation of the brain reward system, a theory supported by evidence that some patients with Parkinson’s disease undergoing dopamine replacement therapy engage in excessive gambling[5].

There is accumulating evidence for the efficacy of new therapeutic strategies for gambling disorder. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) appears to be beneficial[6], especially combined with motivational interviewing[7]. The effectiveness of CBT in mitigating gambling problems was supported by a meta-analytic study[8]. Self-help groups are also available, but their effectiveness is limited[9].

Several pharmacotherapeutic approaches have also been developed. Some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as paroxetine[10] and fluoxetine[11], have been suggested as beneficial. However, they have failed to show effectiveness in large trials[12]. The effect of naltrexone, an opioid receptor blocker, has been controversial in clinical trials[13,14]. Nalmefen, an opioid antagonist approved for alcohol dependence, mitigated obsessive thoughts in one randomized controlled trial[15]. However, establishing the optimal dose of nalmefen remains a challenge[16]. Although the effectiveness of opioid antagonists in treating gambling disorder is still controver

Growing evidence suggests that dopamine D3 receptors play a specific role in the brain reward system. One report indicated that a selective dopamine D3 antagonist reduced methamphetamine-enhanced brain stimulation corresponding to a reward in rats[23,24]. In addition, some dopamine D3 antagonists have been patented for the reduction of drug-induced incentive motivation[25].

Blonanserin is a relatively new antipsychotic drug developed by Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma. It was approved as a schizophrenia medication by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare in April 2008.

Blonanserin has a strong antagonistic effect on dopamine D2 and D3 receptors and on serotonin 5-HT2 receptors[26,27]. In vitro, blonanserin has a stronger affinity for D3 receptors than risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole[28]. Further, an in vivo study with rats showed that blonanserin binds to D3 receptors more strongly than risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole[29]. Recently, researchers have begun to examine the potential effects of blonanserin on mood and anxiety[30]. One case report suggested that blonanserin could effectively suppress pathological alcohol drinking[31], indicating that it could suppress cravings established by the activation of the brain reward system. If this is the case, then blonanserin could be effective in controlling gambling or other maladaptive behaviors in patients with gambling disorder. However, to the best of our knowledge, no clinical trials have investigated the effects of blonanserin on gambling disorder or other impulse control problems.

Blonanserin may be safer than opioid antagonists currently used for treating gambling disorder. For instance, while blonanserin has an antiemetic effect, major opioid antagonists often cause nausea and vomiting. Further, adverse effects regarding metabolism have been scarcely reported. Additionally, blonanserin may improve cognitive function through its D3 receptor antagonism[32]. If a single prescription of blonanserin can mitigate problematic gambling, it may be especially beneficial for patients with nausea and metabolic symptoms. Finally, patients with intellectual disability for whom the effects of CBT may be limited may particularly benefit from blonanserin therapy.

We developed an open-label, non-controlled, exploratory clinical trial. We attempted to recruit three candidates for a pilot study. This number was low due to a limited budget. The clinical protocol is as follows.

Subjects were outpatients of the psychiatry department of Chiba University Hospital, Japan, who had a DSM-5 diagnosis of gambling disorder and were 20-years-old to 64-years-old. Participants should be native Japanese speakers or have equivalent Japanese language skills because several assessments with questionnaire were conducted in this protocol. Candidates were screened using the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS)[33]. Individuals with a SOGS score of 5 or more were included in the clinical trial.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: Lack of competence to participate in clinical trials, pregnancy, any complication of psychoses or organic brain disease (according to F0 or F2 codes in ICD-10), uncontrollable physical complications, having taken antipsychotic medication or D2 receptor blocking drugs in the last 28 d, contraindic

We used several rating scales to screen potential participants in terms of psychiatric status. Individuals were excluded from participation if they scored 15 or over on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale (MADRS)[34], 15 or over on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)[35], or 3 or over on the overall severity scale of the Drug Induced Extra-Pyramidal Symptoms Scale (DIEPSS)[36]. Individuals who had attempted suicide in the last year were also excluded.

Participants took blonanserin twice daily (except for during the first 2 wk, where they took blonanserin once per day) for a total of 8 wk. For safety, the maximum dose was 12 mg/d, which is half the dose approved for patients with schizophrenia in Japan. The dose was increased automatically every 2 wk. The initial dose was 2 mg/d, 4 mg/d in the third and fourth week of the trial, and 8 mg/d in the fifth and sixth weeks. In the seventh and eighth weeks, 8 mg/d was maintained, but the prescriber could increase the dose to 12 mg/d if the efficacy was too low and tolerability was maintained. We set 12 mg/d as the maximum dose in this protocol, which is half of the maximum dose for patients with schizophrenia according to the interview form of blonanserin[37].

Regardless of these guidelines, the daily dose was not increased if a participant had a DIEPSS overall severity score of 1. Additionally, if the DIEPSS overall severity score was 2 or more, the daily dose was decreased to that at the previous visit. Regardless of the DIEPSS score, the prescriber changed the daily dose of blonanserin if any adverse effects occurred.

The prescription was stopped if the prescriber felt that it was necessary or if the participant wished to stop. In this case, however, regular examinations were continued. The prescriber asked participants to take blonanserin immediately after meals because it is not easily absorbed on an empty stomach.

Participation in this trial was terminated if any of the following conditions occurred: Withdrawal of consent by the participant, detection of any contraindication after starting the trial, use of other psychotic drugs in addition to blonanserin, MADRS score > 14, YMRS score > 14, DIEPSS score > 2 on any visit, any intolerable adverse effects of blonanserin, non-compliance (taking less than 70% or more than 120% of the prescribed blonanserin dose), and if the prescriber decided to terminate the trial because of increased symptoms of gambling disorder, medical complications, or other reasons.

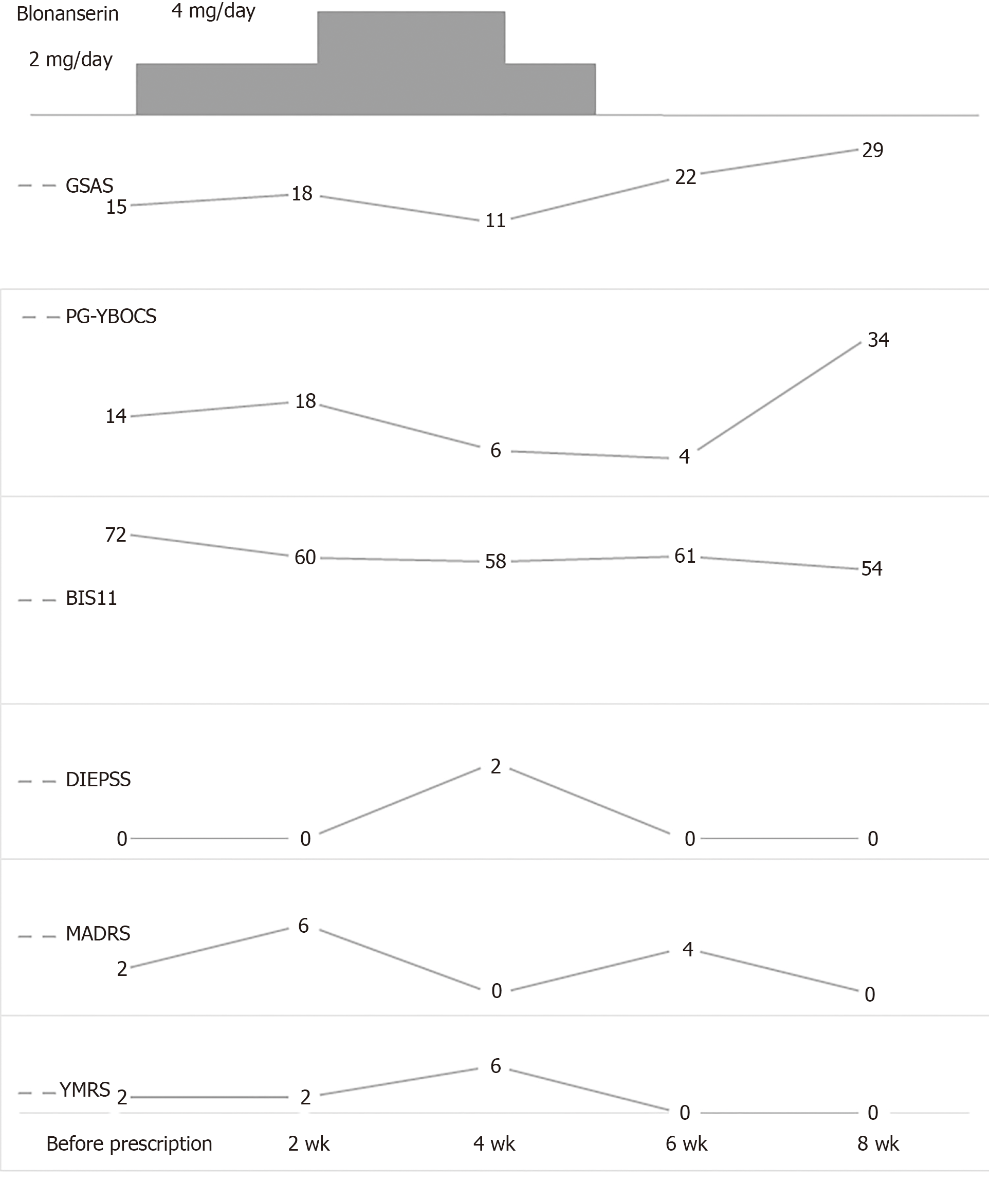

The prescriber assessed participants at every visit (a total of five visits) using the following measures: The Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale (GSAS)[38], the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Pathological Gambling Modification (PG-YBOCS)[39], the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)[40], the DIEPSS, the MADRS, and the YMRS. In addition, a blood examination was conducted 2 and 6 wk after the start of the trial.

The primary outcome measure was the overall DIEPSS severity score at 8 wk. Secondary outcome measures were the change in total scores on the GSAS, the PG-YBOCS, and the BIS-11 between the screening session and 8 wk assessment.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chiba University Hospital, which approved the implementation of this study as a clinical trial on January 7, 2016 (G27039, No. 65). Each participant received an informed consent form containing the entire study protocol including details regarding the potential publication of participant data. The researcher obtained written informed consent from every participant prior to the beginning of the trial. We registered this study protocol with the University Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry on Jan 20, 2016 (R000023855, UMIN000020669).

The present study began in January 2016 and was terminated in March 2017. As this was a pilot study, we set the maximum number of participants at three according to the amount of budget. In reality, only one participant participated in the trial.

The participant was a 37-year-old female with mild intellectual disability and a 20-year history of gambling disorder. The patient also had type I diabetes mellitus and bronchial asthma. She had no other history of mental disorder, and there was no familial history of mental disorder. These details were confirmed by her family doctor. Also, the first author conducted a semi-structural interviewing to confirm her diagnosis.

After obtaining the patient’s informed consent, the prescriber obtained the agreement of the physician to allow the patient to participate in the clinical trial.

The patient took 200 mg/d of sodium valproate, 100 mg/d of trazodone, 15 mg/d of flurazepam, and 0.25 mg/d of triazolam. She was also prescribed 10 mg/d of montelukast, 20 mg/d of metoclopramide, 15 mg/d of lansoprazole, 10 mg/d of cetirizine, and 2 mg/d of chlorpheniramine, and she injected 20 units of insulin aspart daily. There was no evidence suggesting that these medications had any interaction with blonanserin as far as our knowledge and inspection.

At the screening stage, the participant met the DSM-5 criteria for gambling disorder. No other mental disorders were identified other than mild intellectual disability. She received a score of 9 on the SOGS.

After screening, the participant began to take 2 mg/d of blonanserin as an initial dose. After 2 wk, she felt that her craving for gambling had decreased. She complained of temporary mild nausea. According to the protocol, the daily dose of blonanserin was raised to 4 mg/d.

After 4 wk from the start of the trial, she felt mildly joyful. However, she also felt anxious owing to an earthquake that had occurred during the night, and she complained of excessive saliva. As her overall DIEPSS severity score had increased to 2, the blonanserin dose was decreased to 2 mg/d. However, the patient continued to complain of excessive saliva. Therefore, the prescriber withdrew the blonanserin prescription. A couple of weeks later, her saliva production was normal, and no other adverse events were observed.

The DIEPSS overall severity score, which was the primary outcome measure, increased to 2 after the blonanserin dose was raised to 4 mg/d, and the participant experienced excessive saliva production. Because she complained of excessive saliva even after the blonanserin dose was decreased, the blonanserin prescription was stopped. Two weeks after discontinuation, the patient’s complaints had been resolved without any additional intervention.

Scores on the GSAS, PG-YBOCS, and BIS-11 improved following the prescription of blonanserin but deteriorated again after discontinuation of treatment. The MADRS and YMRS scores did not change significantly. None of the scores reached the criteria for trial termination. In addition, the participant did not experience any mood symptoms during the trial (Figure 1).

No medication regimes were changed other than that for blonanserin during the clinical trial term.

The results of blood exams showed no aversive changes during the trial. Her blood sugar (not fasting) decreased from 328 mg/dL at the initial assessment to 242 mg/dL at 6 wk. Her prolactin level decreased from 78.5 ng/mL at the initial assessment to 46.48 ng/mL at the sixth week. Her doctor in charge suggested these changes were clinically acceptable.

We designed the present clinical research protocol to evaluate the efficacy and safety of blonanserin for treating gambling disorder.

The participant showed improvement in GSAS, PG-YBOCS, and BIS-11 scores, but scores deteriorated after blonanserin was discontinued. These findings suggest that blonanserin could suppress gambling cravings. A dose of 4 mg/d is less than the dose used for schizophrenic patients. Blonanserin is likely to have a specific effect on impulsive thoughts, as indicated by the results of a recent rat study[41].

The participant had a mild intellectual disability. In general, patients with intellectual disability do not respond well to cognitive behavioral therapy and experience resistance to treatment of co-occurring mental disorders. For such patients, blonanserin might be an effective alternative to reduce problematic behaviors. While blonanserin improved methamphetamine-induced psychosis in two cases with intellectual disability without adverse effects[42], whether blonanserin is specifically beneficial for patients with intellectual disability remains unclear.

The participant had diabetes. Blonanserin is suggested to be relatively tolerable for patients with metabolic syndrome because it rarely causes weight gain[43]. Also, it seldom raises blood prolactin level[37]. It is interesting that the participant’s blood glucose and prolactin showed improvement through the trial.

Caution is warranted when interpreting the results of a single case study. In addition, the magnitude of the placebo effect is difficult to determine in open-label trials. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trials are needed to measure comprehensively the effects of blonanserin. Also, gender, age, and ethnic differences in blonanserin effect should be examined with further studies with larger sample size.

In the present study, we did not quantitatively evaluate the participant’s cognitive function. A previous report found that blonanserin improved cognitive function in some schizophrenic patients[44]. As there is no evidence that blonanserin can treat symptoms of intellectual disability, we do not believe that the participant’s cognitive function was altered by taking blonanserin. Nonetheless, further investigation is needed to pursue the possibility that the participant’s gambling problems were mitigated through improved cognitive function.

Regarding safety, the participant experienced excessive saliva after taking 4 mg/d of blonanserin. A domestic clinical trial submitted with the approval of the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare found that 75.5% of schizophrenic patients (of whom 35% had parkinsonism) experienced at least one adverse effect when taking blonanserin[37]. In our experience, it is uncommon for patients taking 4 mg/d of blonanserin to complain of adverse effects. The participant in this study may have been sensitive to blonanserin. As blonanserin has high lipid solubility, it remains in the brain for several days after discontinuation. Therefore, it takes time for patients to feel changes after dose modulation. In the present case, the patient took 2 wk to recover from the adverse effects of blonanserin. In clinical settings, doctors in charge should inform patients in advance regarding the pharmacological actions of blonanserin. Salivation can be mitigated with prescription of anticholinergic drugs, but they potentially deteriorate taker’s cognitive function. Doctors should be aware of the management of risk-benefit of these drugs.

We conducted a clinical trial to examine the use of blonanserin to treat gambling disorder. The results suggested that blonanserin might be effective in mitigating gambling behaviors, but that it may also carry a risk of adverse effects. A randomized controlled trial with more detailed monitoring regarding adverse effects is required to test our hypothesis.

Gambling disorder is one type of mental disorders that has a serious impact on patient's life, as well as their families. There have been some treatment strategies developed, but none of them are decisively effective.

There are many who suffer from gambling disorder. We have been engaged in their treatment in the clinical setting, but several patients fail to be respond to treatment due to several reasons. We strongly want to develop treatment options for non-responders.

The aim of the research was to examine the effectiveness and safety of blonanserin, a novel dopamine D3 antagonist, on gambling disorder.

We developed a study protocol in which participants take blonanserin up to 12 mg/d for 8 wk. We evaluated its effect and safety with several rating scales.

One patient participated in this clinical trial. She had improved clinical symptoms of gambling disorder, but due to an adverse effect, quit taking blonanserin.

This case suggests the potential effect of blonanserin to mitigate the symptoms of gambling disorder. On the other hand, extrapyramidal side effect should be cautiously addressed.

We believe the study protocol presented is applicable to a randomized controlled trial with larger sample size.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ge X, Quintero G S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Mishra S, Lalumière ML, Morgan M, Williams RJ. An examination of the relationship between gambling and antisocial behavior. J Gambl Stud. 2011;27:409-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sproston K, Erens B, Orford J. Gambling Behaviour in Britain: Results from the British Gambling Prevalence Survey. Report for the National Centre for Social Research, London, UK, 2000. |

| 3. | Probst CC, van Eimeren T. The functional anatomy of impulse control disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13:386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Łabuzek K, Beil S, Beil-Gawełczyk J, Gabryel B, Franik G, Okopień B. The latest achievements in the pharmacotherapy of gambling disorder. Pharmacol Rep. 2014;66:811-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ahlskog JE. Pathological behaviors provoked by dopamine agonist therapy of Parkinson's disease. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:168-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cowlishaw S, Merkouris S, Dowling N, Anderson C, Jackson A, Thomas S. Psychological therapies for pathological and problem gambling. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD008937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Petry NM, Ginley MK, Rash CJ. A systematic review of treatments for problem gambling. Psychol Addict Behav. 2017;31:951-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gooding P, Tarrier N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural interventions to reduce problem gambling: hedging our bets? Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:592-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | National Research Council. Pathological gambling: A critical review. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1999. |

| 10. | Kim SW, Grant JE, Adson DE, Shin YC, Zaninelli R. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of paroxetine in the treatment of pathological gambling. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:501-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Finkell JN, Begaz T, Wong CM, Cartwright C. A randomized double-blind fluvoxamine/placebo crossover trial in pathologic gambling. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:813-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grant JE, Kim SW, Potenza MN, Blanco C, Ibanez A, Stevens L, Hektner JM, Zaninelli R. Paroxetine treatment of pathological gambling: a multi-centre randomized controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grant JE, Kim SW, Hartman BK. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist naltrexone in the treatment of pathological gambling urges. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:783-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Toneatto T, Brands B, Selby P. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone in the treatment of concurrent alcohol use disorder and pathological gambling. Am J Addict. 2009;18:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Grant JE, Potenza MN, Hollander E, Cunningham-Williams R, Nurminen T, Smits G, Kallio A. Multicenter investigation of the opioid antagonist nalmefene in the treatment of pathological gambling. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:303-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Potenza MN, Hollander E, Kim SW. Nalmefene in the treatment of pathological gambling: multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:330-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Victorri-Vigneau C, Spiers A, Caillet P, Bruneau M; Ignace-Consortium; Challet-Bouju G, Grall-Bronnec M. Opioid Antagonists for Pharmacological Treatment of Gambling Disorder: Are they Relevant? Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:1418-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Goslar M, Leibetseder M, Muench HM, Hofmann SG, Laireiter AR. Pharmacological Treatments for Disordered Gambling: A Meta-analysis. J Gambl Stud. 2019;35:415-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fong T, Kalechstein A, Bernhard B, Rosenthal R, Rugle L. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine for the treatment of video poker pathological gamblers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:298-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cohen J, Magalon D, Boyer L, Simon N, Christophe L. Aripiprazole-induced pathological gambling: a report of 3 cases. Curr Drug Saf. 2011;6:51-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Smith N, Kitchenham N, Bowden-Jones H. Pathological gambling and the treatment of psychosis with aripiprazole: case reports. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:158-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kraus SW, Etuk R, Potenza MN. Current pharmacotherapy for gambling disorder: a systematic review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21:287-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Micheli F, Bonanomi G, Blaney FE, Braggio S, Capelli AM, Checchia A, Curcuruto O, Damiani F, Fabio RD, Donati D, Gentile G, Gribble A, Hamprecht D, Tedesco G, Terreni S, Tarsi L, Lightfoot A, Stemp G, Macdonald G, Smith A, Pecoraro M, Petrone M, Perini O, Piner J, Rossi T, Worby A, Pilla M, Valerio E, Griffante C, Mugnaini M, Wood M, Scott C, Andreoli M, Lacroix L, Schwarz A, Gozzi A, Bifone A, Ashby CR Jr, Hagan JJ, Heidbreder C. 1,2,4-triazol-3-yl-thiopropyl-tetrahydrobenzazepines: a series of potent and selective dopamine D(3) receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5076-5089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Spiller K, Xi ZX, Peng XQ, Newman AH, Ashby CR Jr, Heidbreder C, Gaál J, Gardner EL. The selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonists SB-277011A and NGB 2904 and the putative partial D3 receptor agonist BP-897 attenuate methamphetamine-enhanced brain stimulation reward in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2008;196:533-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Micheli F, Heidbreder C. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists: a patent review (2007 - 2012). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2013;23:363-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Murasaki M. Preclinical characteristic and clinical positioning of blonanserin for schizophrenia. Jap J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;11:461-476. |

| 27. | Tenjin T, Miyamoto S, Ninomiya Y, Kitajima R, Ogino S, Miyake N, Yamaguchi N. Profile of blonanserin for the treatment of schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:587-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tadori Y, Forbes RA, McQuade RD, Kikuchi T. Functional potencies of dopamine agonists and antagonists at human dopamine D₂ and D₃ receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;666:43-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Baba S, Enomoto T, Horisawa T, Hashimoto T, Ono M. Blonanserin extensively occupies rat dopamine D3 receptors at antipsychotic dose range. J Pharmacol Sci. 2015;127:326-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Limaye RP, Patil AN. Blonanserin - A Novel Antianxiety and Antidepressant Drug? J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:FC17-FC21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Takaki M, Ujike H. Blonanserin, an antipsychotic and dopamine D₂/D₃receptor antagonist, and ameliorated alcohol dependence. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36:68-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Inoue T, Osada K, Tagawa M, Ogawa Y, Haga T, Sogame Y, Hashizume T, Watanabe T, Taguchi A, Katsumata T, Yabuki M, Yamaguchi N. Blonanserin, a novel atypical antipsychotic agent not actively transported as substrate by P-glycoprotein. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39:156-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1184-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1864] [Cited by in RCA: 1834] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9039] [Cited by in RCA: 9811] [Article Influence: 213.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5767] [Cited by in RCA: 6415] [Article Influence: 136.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Inada T. Evaluation and diagnosis of drug‐induced extrapyramidal symptoms: commentary on the DIEPSS and guide to its usage. Seiwa Shoten Publishers 1996. |

| 37. | Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma. Interview form for assessing Lonasen eligibility Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Web site 2018. Available from: https://ds-pharma.jp/product/Lonasen/pdf/Lonasen_tabpow_interv.pdf. |

| 38. | Kim SW, Grant JE, Potenza MN, Blanco C, Hollander E. The Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale (G-SAS): a reliability and validity study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;166:76-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Pallanti S, DeCaria CM, Grant JE, Urpe M, Hollander E. Reliability and validity of the pathological gambling adaptation of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (PG-YBOCS). J Gambl Stud. 2005;21:431-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Nishitani N, Sasamori H, Ohmura Y, Yoshida T, Yoshioka M. Blonanserin suppresses impulsive action in rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2019;141:127-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Okazaki K, Makinodan M, Yamamuro K, Takata T, Kishimoto T. Blonanserin treatment in patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis comorbid with intellectual disabilities. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:3195-3198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kishi T, Matsuda Y, Iwata N. Cardiometabolic risks of blonanserin and perospirone in the management of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Hori H, Yamada K, Kamada D, Shibata Y, Katsuki A, Yoshimura R, Nakamura J. Effect of blonanserin on cognitive and social function in acute phase Japanese schizophrenia compared with risperidone. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:527-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |