Published online Jan 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.236

Peer-review started: September 20, 2020

First decision: October 17, 2020

Revised: October 30, 2020

Accepted: November 9, 2020

Article in press: November 9, 2020

Published online: January 6, 2021

Processing time: 99 Days and 23.8 Hours

Hemosuccus pancreaticus is a very rare but severe form of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The most common etiology is peripancreatic pseudoaneurysm secondary to chronic pancreatitis. Due to the rarity of gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysms, most of the current literature consists of case reports. Limited knowledge about the disease causes diagnostic difficulty.

A 39-year-old man with a previous history of chronic pancreatitis was hospitalized due to hematemesis and melena for 2 wk, with a new episode lasting 1 d. Two weeks prior, the patient had visited a local hospital for repeated hematemesis and melena. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy indicated hemorrhage in the descending duodenum. The patient was discharged after the bleeding stopped, but hematemesis and hematochezia recurred. Bedside esophago-gastroduodenoscopy showed no obvious bleeding lesion. On admission to our hospital, he had hematemesis, hematochezia, left middle and upper abdominal pain, severe anemia, and elevated blood amylase. After admission, intermittent hematochezia was observed. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a pseudoaneurysm in the pancreas head. Angiography confirmed the diagnosis of gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm. The pseudoaneurysm was successfully embolized with a coil and cyanoacrylate. No bleeding was observed after the operation. After discharge from the hospital, a telephone follow-up showed no further bleeding signs.

Hemosuccus pancreaticus caused by gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm associated with chronic pancreatitis is very rare. This diagnosis should be considered when upper gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal pain are intermittent. Abdominal enhanced computed tomography and angiography are important for diagnosis and treatment.

Core Tip: Hemosuccus pancreaticus (HP) caused by gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm associated with chronic pancreatitis is a very rare but severe form of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Limited knowledge about the disease causes diagnostic difficulty. Here, we present a case of HP caused by gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm associated with chronic pancreatitis, which was diagnosed by abdominal enhanced computed tomography and angiography and treated with transarterial embolization. The diagnosis of HP should be considered when upper gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal pain are intermittent. Abdominal enhanced computed tomography and angiography are important for diagnosis and treatment.

- Citation: Cui HY, Jiang CH, Dong J, Wen Y, Chen YW. Hemosuccus pancreaticus caused by gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm associated with chronic pancreatitis: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(1): 236-244

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i1/236.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.236

Hemosuccus pancreaticus (HP) refers to the phenomenon of bleeding from the ampulla of Vater via the pancreatic duct to the intestine. The diagnosis of HP is very difficult. Intermittent abdominal pain and intermittent bleeding are characteristic manifestations of HP[1]. Angiography is currently the most widely used method for diagnosing HP, which has a sensitivity of 96%[2]. For treatment, angiography with endovascular embolization is reliable and minimally invasive and has a success rate of approximately 79%-100%[3].

HP is extremely rare, and only approximately 150 cases have been reported in the worldwide literature to date[4]. Peripancreatic pseudoaneurysm occurs in approximately 10% to 17% of all chronic pancreatitis[5], which is the main cause of HP[6]. The gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm associated with chronic pancreatitis is the second cause of HP, accounting for approximately 10%-20% of HP cases[7]. This article reports a case of HP caused by gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to chronic pancreatitis, which was successfully treated with endovascular embolization for hemostasis.

A 39-year-old man was admitted to the hospital due to hematemesis and melena for 2 wk, with a new episode lasting 1 d.

Two weeks before admission, the patient had hematemesis and melena without obvious known causes. He vomited light red fluids 4-5 times/d and passed tarry stools 3-4 times/d; these events were accompanied by epigastric pain, abdominal distension, and fatigue. He had no dizziness or syncope. He was hospitalized at a local hospital where examinations showed a hemoglobin (Hb) level of 86 g/L. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed fresh blood in the descending part of the duodenum but did not show a clear bleeding site. The patient was treated with blood transfusion, acid blockers, and intravenous (IV) fluid and discharged from the hospital after no recurrence of hematemesis or melena was observed.

One day before admission to our hospital, the patient vomited bright red blood once and was admitted to the local hospital. Bedside EGD showed no obvious bleeding in the upper gastrointestinal tract. During his hospitalization, the patient had repeated hematemesis and hematochezia 4-5 times/d accompanied by left upper abdominal pain and fatigue. His minimum Hb level was 42 g/L. After treatment with blood transfusion, IV fluid, acid blockers, and hemostasis, he was transferred to our hospital for emergency admission.

The patient had a history of chronic pancreatitis. He denied chronic diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, and diabetes, a history of abdominal surgery and trauma, and a history of food and drug allergy.

The patient denied a history of smoking and drinking and any history of diseases in family members.

On admission, the patient had a body temperature of 37.2 °C, a pulse of 102 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 19 times/min, a blood pressure of 117/91 mmHg, and an oxygen saturation of 98%. The patient had manifestations of anemia and pale conjunctiva. His abdomen was soft with upper abdominal tenderness. No rebound tenderness was noted. No abdominal mass was palpable. No other obvious abnormality was noted.

The complete blood count on admission was as follows: White blood cell count, 8.00 × 109/L; red blood cell count, 2.34 × 109/L; Hb, 66 g/L; hematocrit, 0.192; platelet count, 108 × 109/L; total amylase, 198 U/L; D-dimer, 6060 µg/L; hypersensitive C-reactive protein, 40.1 mg/L; procalcitonin, 0.12 ng/mL; and serum albumin, 24 g/L (Table 1). Coagulation function, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, glutamyl transpeptidase, urinalysis results, stool analysis, tumor marker expression, troponin I, and electrocardiogram results were all within normal limits.

| Complete blood count | Results | Reference range | Unit |

| White blood cell count | 8.00 | 3.50-9.50 | 109/L |

| Red blood cell count | 2.34 | 4.30-5.80 | 109/L |

| Hemoglobin | 66 | 130-175 | g/L |

| Hematocrit | 0.192 | 0.400-0.500 | |

| Platelet count | 108 | 125-350 | 109/L |

| Total amylase | 198 | 30-100 | U/L |

| D-dimer | 6060 | 0-500 | µg/L |

| C-reactive protein | 40.1 | 0.0-10.0 | mg/L |

| Procalcitonin | 0.12 | 0.00-0.50 | ng/mL |

| Serum albumin | 24 | 40-55 | g/L |

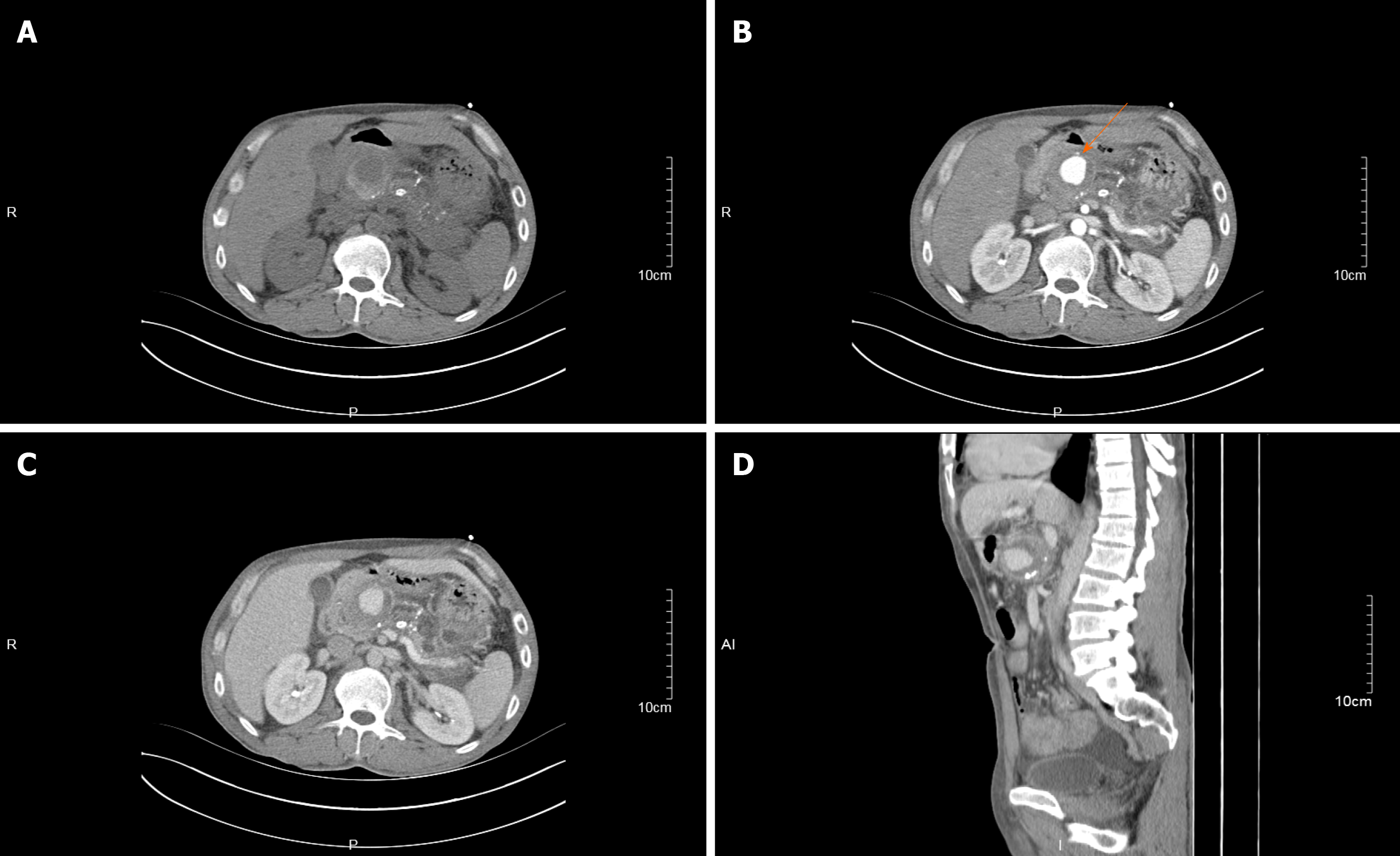

A noncontrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed pancreatic swelling, uneven density, vague edges, multiple spots of calcifications, and hyperintense opacities in the pancreatic head and body, indicating chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic head hemorrhage.

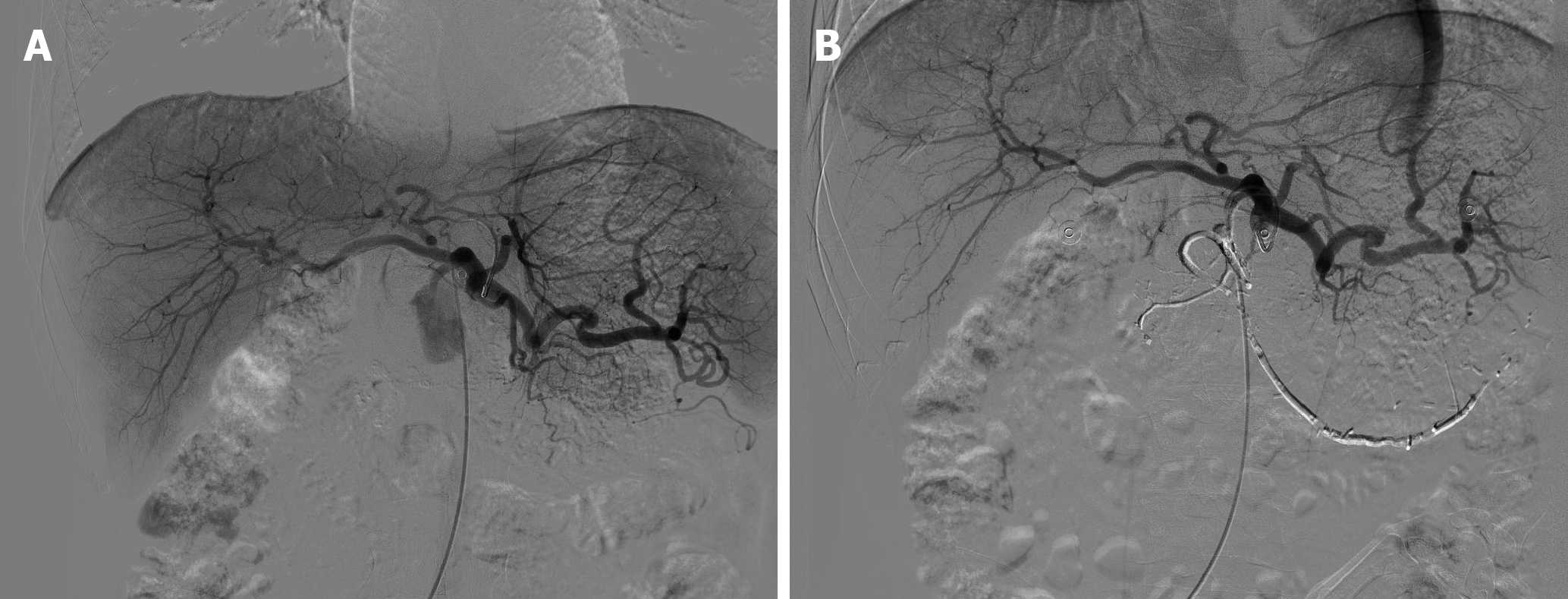

Subsequent contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen showed isointense, rounded opacities with a diameter of approximately 41 mm in the pancreatic head that were enhanced with contrast in the arterial phase and were closely related to the gastroduodenal artery, indicating pseudoaneurysm (Figure 1). Furthermore, digital subtraction angiography performed via the celiac trunk showed the formation of pseudoaneurysms at the proximal gastroduodenal artery; the remaining blood vessels were unremarkable (Figure 2A, Video 1A).

The patient was diagnosed with HP caused by gastroduodenal artery pseudo-aneurysm associated with chronic pancreatitis.

Before the diagnosis was confirmed, the patient was treated with a transfusion of 6 U of red blood cells and 230 mL plasma, IV fluids, and acid blockers. A repeated test showed that the total blood amylase level had dropped to normal (75 U/L), and the Hb concentration fluctuated between 46 and 67 g/L. The patient still had repeated hemorrhaging and melena with intermittent upper abdominal pain. After the diagnosis of gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm was confirmed, the pseudoaneurysm was embolized with a 4 mm × 4 mm coil, and the vessels proximal and distal to the pseudoaneurysm were embolized with an appropriate amount of medical glue (Figure 2B, Video 1B). After the operation, 5 U of red blood cells were transfused, and IV fluids were given.

After the operation, no hematemesis or hematochezia was reported, and the patient’s Hb level increased to 82 g/L. Upper abdominal pain was improved. At a telephone follow-up 2 mo after discharge from the hospital, the patient presented no symptoms of hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, or abdominal pain.

HP is the phenomenon of bleeding from the ampulla of Vater via the pancreatic duct to the intestine. HP was first described by Lower and Farrell[8] in 1931. In 1970, Sandblom[9] first used the term HP. HP is a rare but severe form of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The degree of HP ranges from intermittent small bleeds to acute massive bleeding, and severe bleeding can lead to death[1]. The disease is very rare, and only approximately 150 cases have been reported in the worldwide literature to date[4]. Most cases have been reported in case reports or single center case series[10]. Only 21 cases of HP caused by gastroduodenal pseudoaneurysm have been reported in the English-language literature between 1977 and September 2020. Table 2 summarized the salient clinical features of 118 cases of HP published in the English literature.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Causes | 118 |

| Splenic artery pseudoaneurysm | 23 (19.5) |

| Gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm | 21 (17.8) |

| Other aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms | 37 (31.4) |

| Pancreatic tumors | 14 (11.9) |

| Vascular diseases | 8 (6.8) |

| EUS-FNA | 3 (2.5) |

| Surgery | 2 (1.7) |

| Trauma | 1 (0.8) |

| Unclear causes | 9 (7.6) |

| Symptoms | |

| Melena | 62 (52.5) |

| Abdominal pain | 54 (45.8) |

| Hematemesis | 31 (26.3) |

| Hematochezia | 16 (13.6) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 11 (9.3) |

| Lab results | |

| Hyperamylasemia | 5 (4.2) |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 2 (1.7) |

| Endoscopic findings | 118 |

| Positive1 | 56 (47.5) |

| Negative2 | 62 (52.5) |

| Imaging findings | 118 |

| Positive3 | 74 (62.7) |

| Negative4 | 44 (37.2) |

| Treatment | 118 |

| Artery embolization | 52 (44.1) |

| Surgery | 45 (38.1) |

| Stent placement | 9 (7.6) |

| Conservative treatment | 9 (7.6) |

| Thrombin injection | 4 (3.4) |

The causes of HP include pancreatic inflammation, vascular lesions, tumors, surgery, and trauma. Peripancreatic pseudoaneurysm occurs in approximately 10% to 17% of all chronic pancreatitis[5], which is the main cause of HP[6]. The possible mechanism is that during the progression of pancreatic inflammation, pancreatic enzymes (mainly elastase) can erode the pancreatic blood vessels and tissues by proteolysis, causing vascular rupture and cyst formation; the resulting communication between the cyst and the artery forms a pseudoaneurysm. When the aneurysm ruptures into the pancreatic duct, it manifests as a pancreatic hemorrhage[7]. The main site of visceral pseudoaneurysm formation is the splenic artery (60%)[6]; other affected arteries include the superior mesenteric artery[10], celiac trunk[11], cystic artery[12], right hepatic artery[13], and inferior mesenteric artery[3]. The gastroduodenal artery is a rare site for visceral pseudoaneurysms, and its incidence rate are reported between approximately 1.5%[14] and 20%[7] of all visceral pseudoaneurysms. Given the rarity of the disease, the data may be biased. However, the gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm is the second cause of HP, only next to splenic artery according to the current English-language literature.

The diagnosis of HP is very difficult. The symptoms may vary among patients and are not typical in some cases. Thus, the disease is very easily missed or misdiagnosed. Common symptoms of HP include abdominal pain (52%, usually upper abdominal pain) and gastrointestinal bleeding symptoms (46%, melena, hematochezia, and hematemesis)[15]. Other possible clinical signs include hyperamylasemia[16], jaundice[17], nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, and a palpable upper abdominal pulsating mass[1].

Intermittent abdominal pain and intermittent bleeding are characteristic manifestations of HP[1]. The possible mechanism is blood clots blocking the pancreatic duct and causing increased pressure in the duct. As a result, bleeding is stopped, but abdominal pain may persist. After a period of time (from tens of minutes to several days), the blood clots are dissolved and passed, and the pressure in the pancreatic duct is reduced. At that time, the abdominal pain is relieved, but gastrointestinal bleeding resumes. The mechanism of hyperamylasemia remains unclear. Galanakis et al[16] proposed two explanations. One explanation is that the formation of blood clots in the pancreatic duct causes partial or full obstruction, which manifests as transient hyperamylasemia or hyperbilirubinemia. The other explanation is that due to the anatomical proximity of the gastroduodenal artery and the pancreaticobiliary drainage system, an aneurysm or a closed hematoma may cause exogenous compression of the common bile duct and main pancreatic duct. The former condition may explain the hyperamylasemia in the patient described in this case. This patient had intermittent abdominal pain, intermittent bleeding, and elevated amylase, leading to a suspicion of HP.

Early confirmed diagnosis and intervention are very important. HP can cause fatal bleeding due to aneurysm rupture, and the risk is not related to the size of the pseudoaneurysm[18]. With the continuous development of technology, available diagnostic methods include EGD, CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), angiography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography[19,20], endoscopic ultrasound[14], Doppler ultrasound[21,22], and the radionuclide tracer technique[20]. EGD is the necessary and preferred method for diagnosing upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The presence of bright blood from the duodenal papilla during the operation is a direct sign of HP. Even if active bleeding from the ampulla cannot be observed, other diseases that can cause upper gastrointestinal bleeding (such as peptic ulcer, erosion hemorrhagic gastritis, and tumors) can be ruled out by normal EGD findings. If blood of an unknown origin is found in the descending part of the duodenum, HP should be suspected[20]. Sometimes, however, HP can be difficult to diagnose using EGD. Due to the characteristics of intermittent bleeding in HP, more than half of EGD results may be normal[23,24]. In addition, the duodenal papilla in some patients cannot be observed during EGD. A side-viewing duodenoscope can be used in this situation to observe whether bleeding from the ampulla is present. Therefore, in patients with recurring or persistent gastrointestinal bleeding, EGD should be performed repeatedly, or a side-viewing duodenoscope should be used.

Contrast-enhanced CT, CT angiography, or MRI are useful for diagnosing pseudoaneurysms. Among these techniques, abdominal contrast-enhanced CT is more convenient and efficient for primary diagnosis. Contrast-enhanced CT and CT angiography can simultaneously show arteries, aneurysms, and structures around the pancreas in the arterial phase, while continuous enhancement can be observed in pseudocysts in the venous phase[25]. In this case, if this patient had undergone an abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan, his pseudoaneurysm might have been found earlier. MRI can be used as an alternative examination method for people who are allergic to iodine. MRI can reveal a small amount of blood in the pancreatic duct and duodenum and can also be used to distinguish pseudocysts from abscesses[26]. Angiography is currently the most widely used method for diagnosing and treating HP and has a sensitivity of 96%[2]. Angiography can reveal the parent blood vessel that is bleeding and can clearly show the anatomy of the target blood vessel and surrounding blood vessels. However, angiography has limitations, as it cannot accurately locate the diseased blood vessel in cases with minor or intermittent bleeding. In such cases, the diagnosis of HP usually requires the use of multiple methods. In the present case, EGD, abdominal contrast-enhanced CT, and digital subtraction angiography were used to confirm the diagnosis.

After the bleeding vessel is identified, the bleeding lesion must be treated immediately. Even after treatment, the mortality rate is still 25%-37% in patients with severe bleeding[27]. At present, the preferred treatment method is endovascular embolization to achieve hemostasis. This technique is reliable and minimally invasive with a success rate of approximately 79%-100%[3]. Coils are commonly used embolic materials[28]. A coil is packed into the lumen of the pseudoaneurysm to cause complete thrombosis; the lumen opening is then closed with the coil, and the distal and proximal ends of the parent vessel are embolized to ensure that the aneurysm is isolated from the blood circulation. Other embolic materials that can be used include n-butyl-cyanoacrylates[29], Spongostan[30], and thrombin[31]. The maximum probability of rebleeding is approximately 37% in patients who undergo vascular embolization[22]. The specific mechanism of rebleeding is not clear but may be related to the opening of collateral vessels. Some patients require re-embolization. A covered stent can be used for aneurysms in a large artery (such as the abdominal trunk) or a single artery without collateral circulation. Such stents cover the opening of the aneurysm to prevent blood from entering the aneurysm body while maintaining the patency of the blood vessels, thereby preventing ischemia in other tissues. Surgical treatment is a classic treatment method. However, due to the greater associated trauma, surgery is most suitable for patients for whom vascular interventional therapy has failed, those with unstable vital signs, and those requiring laparotomy (for example, when the bleeding site cannot be located on examination).

The patient in the present case was diagnosed with HP caused by gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm associated with chronic pancreatitis and underwent coil and cyanoacrylate embolization in the distal and proximal parent blood vessel. No gastrointestinal bleeding was reported after the operation.

This article reports a case of HP caused by gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to chronic pancreatitis, which was successfully treated with endovascular embolization for hemostasis. HP is a very rare disease, and the characteristic symptoms are intermittent abdominal pain and intermittent gastrointestinal bleeding. Missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis are common, thus complicating the clinical diagnosis. HP should be considered when upper gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal pain are intermittent. Abdominal CT and digital subtraction angiography are important for confirming the diagnosis and treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Inchingolo R, Jha AK, Mikulic D, Qayed E S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Koren M, Kinova S, Bedeova J, Javorka V, Kovacova E, Kekenak L. Hemosuccus pancreaticus. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2008;109:37-41. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kim SS, Roberts RR, Nagy KK, Joseph K, Bokhari F, An G, Barrett J. Hemosuccus pancreaticus after penetrating trauma to the abdomen. J Trauma. 2000;49:948-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Binetti M, Lauro A, Golfieri R, Vaccari S, D'Andrea V, Marino IR, Cervellera M, Renzulli M, Tonini V. False in Name Only-Gastroduodenal Artery Pseudoaneurysm in a Recurrently Bleeding Patient: Case Report and Literature Review. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:3086-3091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Inayat F, Ali NS, Khan M, Munir A, Ullah W. Hemosuccus Pancreaticus: A Great Masquerader in Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Cureus. 2018;10:e3785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | de Perrot M, Berney T, Bühler L, Delgadillo X, Mentha G, Morel P. Management of bleeding pseudoaneurysms in patients with pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:29-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Han B, Song ZF, Sun B. Hemosuccus pancreaticus: a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012;11:479-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Volpi MA, Voliovici E, Pinato F, Sciuto F, Figoli L, Diamant M, Perrone LR. Pseudoaneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery secondary to chronic pancreatitis. Ann Vasc Surg 2010; 24: 1136.e7-1136. 11;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lower WE, Farrell JI. Aneurysm of the splenic artery: Report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Surg. 1931;23: :182-190. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sandblom P. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage through the pancreatic duct. Ann Surg. 1970;171:61-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saqib NU, Ray HM, Al Rstum Z, DuBose JJ, Azizzadeh A, Safi HJ. Coil embolization of a ruptured gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm presenting with hemosuccus pancreaticus. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2020;6:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abdelgabar A, d'Archambeau O, Maes J, Van den Brande F, Cools P, Rutsaert RR. Visceral artery pseudoaneurysms: two case reports and a review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | She WH, Tsang S, Poon R, Cheung TT. Gastrointestinal bleeding of obscured origin due to cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. Asian J Surg. 2017;40:320-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fujio A, Usuda M, Ozawa Y, Kamiya K, Nakamura T, Teshima J, Murakami K, Suzuki O, Miyata G, Mochizuki I. A case of gastrointestinal bleeding due to right hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm following total remnant pancreatectomy: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;41:434-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sharma M, Somani P. Endoscopic ultrasound of gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm. Endoscopy. 2017;49:E117-E118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sethi H, Peddu P, Prachalias A, Kane P, Karani J, Rela M, Heaton N. Selective embolization for bleeding visceral artery pseudoaneurysms in patients with pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9:634-638. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Galanakis V. Pseudoaneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery: an unusual cause for hyperamylasaemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yen YT, Lai HW, Lin CH. Endovascular salvage for contained rupture of gastroduodenal artery aneurysm presented with obstructive jaundice. Ann Vasc Surg 2015; 29: 1017.e1-1017. e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Matsuno Y, Mori Y, Umeda Y, Imaizumi M, Takiya H. Surgical repair of true gastroduodenal artery aneurysm: a case report. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2008;42:497-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Clay RP, Farnell MB, Lancaster JR, Weiland LH, Gostout CJ. Hemosuccus pancreaticus. An unusual cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Surg. 1985;202:75-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG, Farley DR, Que FG, Andrews JC, Farnell MB. Hemosuccus pancreaticus complicating chronic pancreatitis: an obscure cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2000;385:124-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Benz CA, Jakob P, Jakobs R, Riemann JF. Hemosuccus pancreaticus--a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding: diagnosis and interventional radiological therapy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:428-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Boudghène F, L'Herminé C, Bigot JM. Arterial complications of pancreatitis: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects in 104 cases. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1993;4:551-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shnayder MM, Mohan P. Hemosuccus pancreaticus from superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysm within perceived pancreatic mass. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2019;12:88-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rammohan A, Palaniappan R, Ramaswami S, Perumal SK, Lakshmanan A, Srinivasan UP, Ramasamy R, Sathyanesan J. Hemosuccus Pancreaticus: 15-Year Experience from a Tertiary Care GI Bleed Centre. ISRN Radiol. 2013;2013:191794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bohl JL, Dossett LA, Grau AM. Gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm associated with hemosuccus pancreaticus and obstructive jaundice. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1752-1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shetty S, Shenoy S, Costello R, Adeel MY, Arora A. Hemosuccus Pancreaticus. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2019;31:622-626. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Anil Kothari R, Leelakrishnan V, Krishnan M. Hemosuccus pancreaticus: a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:175-177. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Cerrato DR, Beteck B, Sardana N, Farooqui S, Allen D, Cunningham SC. Hemosuccus pancreaticus due to a noninflammatory pancreatic pseudotumor. JOP. 2014;15:501-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Won Y, Lee SL, Kim Y, Ku YM. Clinical efficacy of transcatheter embolization of visceral artery pseudoaneurysms using N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA). Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:563-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Czernik M, Stefańczyk L, Szubert W, Chrząstek J, Majos M, Grzelak P, Majos A. Endovascular treatment of pseudoaneurysms in pancreatitis. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2014;9:138-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Barbiero G, Battistel M, Susac A, Miotto D. Percutaneous thrombin embolization of a pancreatico-duodenal artery pseudoaneurysm after failing of the endovascular treatment. World J Radiol. 2014;6:629-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |