Published online May 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i9.1705

Peer-review started: March 11, 2020

First decision: April 1, 2020

Revised: April 9, 2020

Accepted: April 17, 2020

Article in press: April 17, 2020

Published online: May 6, 2020

Processing time: 50 Days and 0.2 Hours

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has become an immense public health burden, first in China and subsequently worldwide. Developing effective control measures for COVID-19, especially measures that can halt the worsening of severe cases to a critical status is of urgent importance.

A 52-year-old woman presented with a high fever (38.8 °C), chills, dizziness, and weakness. Epidemiologically, she had not been to Wuhan where COVID-19 emerged and did not have a family history of a disease cluster. A blood test yielded a white blood cell count of 4.41 × 109/L (60.6 ± 2.67% neutrophils and 30.4 ± 1.34% lymphocytes). Chest imaging revealed bilateral ground-glass lung changes. Based on a positive nasopharyngeal swab nucleic acid test result and clinical characteristics, the patient was diagnosed with COVID-19. Following treatment with early non-invasive ventilation and a bundle pharmacotherapy, she recovered with a good outcome.

Early non-invasive ventilation with a bundle pharmacotherapy may be an effective treatment regimen for the broader population of patients with COVID-19.

Core tip: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has become a public health emergency of international concern. Establishing effective control measures is of urgent importance. We here report a case of severe COVID-19. The patient was treated successfully with early non-invasive ventilation when her arterial oxygen partial pressure/fractional inspired oxygen ratio dropped below 200 mmHg, and a bundle pharmacotherapy which included an antiviral cocktail (lopinavir/ritonavir plus α-interferon), an immunity enhancer (thymosin), a corticosteroid to reduce pulmonary exudation (methylprednisolone), a traditional Chinese medicine-derived anti-inflammatory prescription (Xuebijing), and an anti-coagulant to prevent deep vein thrombosis (heparin). Early non-invasive ventilation with a bundle pharmacotherapy may be an effective regimen for patients with COVID-19.

- Citation: Peng M, Ren D, Liu XY, Li JX, Chen RL, Yu BJ, Liu YF, Meng X, Lyu YS. COVID-19 managed with early non-invasive ventilation and a bundle pharmacotherapy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(9): 1705-1712

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i9/1705.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i9.1705

Disease severity associated with the ongoing pandemic caused by infection with the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) varies substantially, with the primary symptoms being fever, cough, and shortness of breath, and a potential for the development of pneumonia and other sequelae. A cluster of cases occurred in the Huanan seafood market in the Jianghan District of Wuhan, Hubei Province, China in December 2019[1]. Although the source, route, and extent of transmission of the 2019-nCoV were not fully clear, a panel of experts assigned by the National Health Commission of China believed that it could be transmitted from person to person[2].

Most patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV infection and consequent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) exhibit fever, radiographic ground-glass lung changes, a normal (or low) white blood cell count (WCC), and hypoxemia. Meanwhile, some people have tested positive for 2019-nCoV without developing a fever or other serious symptoms[3,4]. So far, there is no standard treatment for COVID-19, especially effective measures that can prevent worsening of the illness. Here, we report a case of a patient who had severe COVID-19 with fever and was treated successfully.

On admission to our department, she complained of persistent body aches that had begun 10 d previously, a sporadic cough with white sputum, and 1 d of fever.

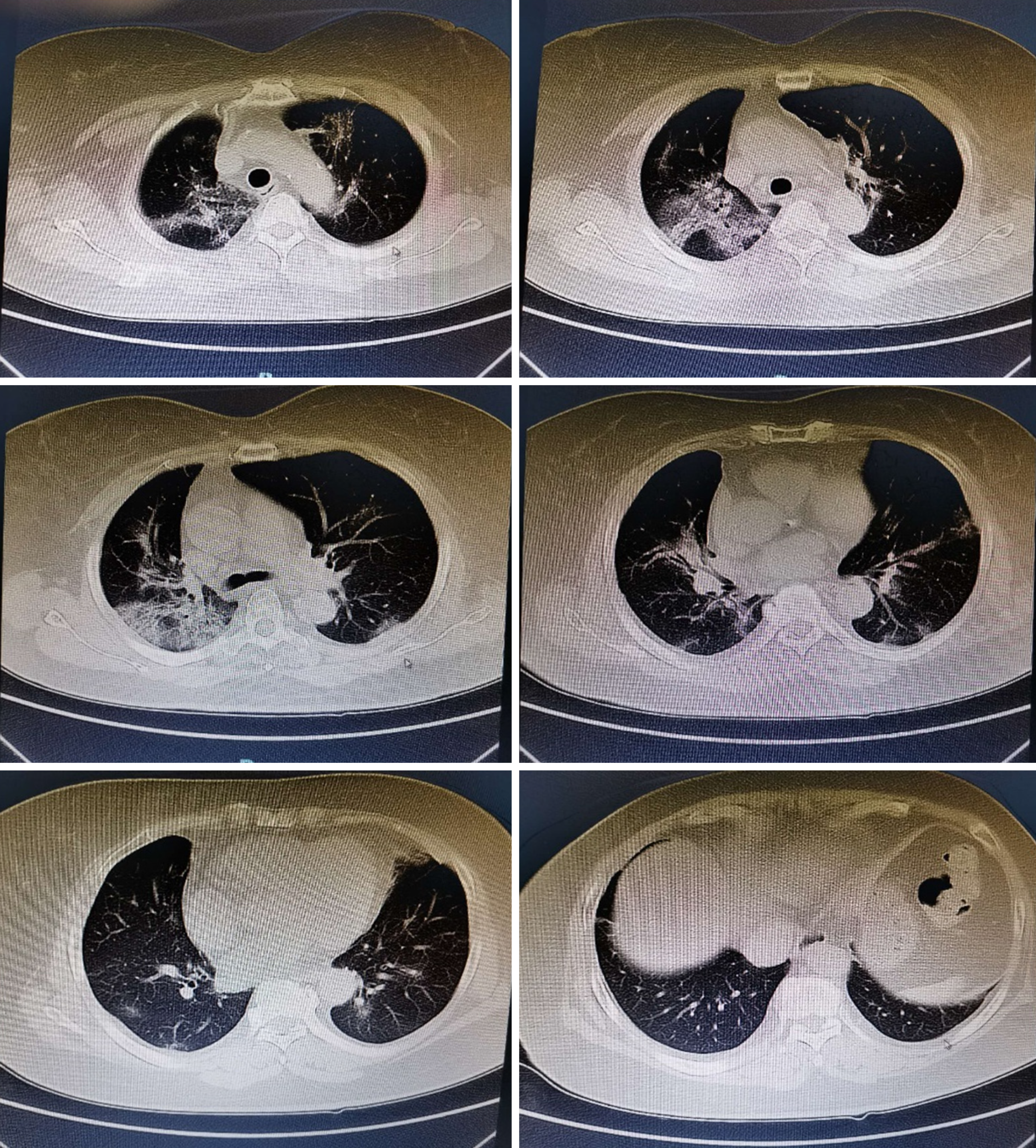

One day before being admitted to our hospital (7 pm, January 25, 2020), a 52-year-old woman (body mass index, 24.4) presented at Shenzhen People’s Hospital with a high fever (38.8 °C), chills, dizziness, and weakness. As an outpatient there, she underwent a chest computed tomography scan (CT) that showed signs of possible viral pneumonia (Figure 1). Consequently, she was isolated immediately and transferred within a day by a negative pressure ambulance to our institution, the Third People’s Hospital of Shenzhen, which is a designated hospital for COVID-19 .

Besides the chief complaints mentioned above, she indicated that she had not experienced shortness of breath, chest tightness, or chest pain. She reported that she had taken an antibiotic (potassium amoxicillin clavulinate dispersible tablets) and golden lotus (traditional Chinese medicine soft capsules) but achieved no relief.

Her medical history included hypertension and gout, but she was not taking any medications on regular basis.

Epidemiologically, she had not been to Wuhan in the past year and did not have a family history of a disease cluster.

At the time of admission, she had a fever of 38 °C, a respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min, a heart rate of 87 beats/min, and a blood pressure of 154/79 mmHg. No other abnormal findings were revealed by physical examination.

A blood test yielded a WCC of 4.41 × 109/L (60.6% ± 2.67% neutrophils and 30.4% ± 1.34% lymphocytes). Arterial blood gas testing showed an arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) of 52.8 mmHg with 21% of fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2), yielding a PaO2/FiO2 ratio (P/F ratio) of 251 mmHg. Renal and liver function test results were unremarkable.

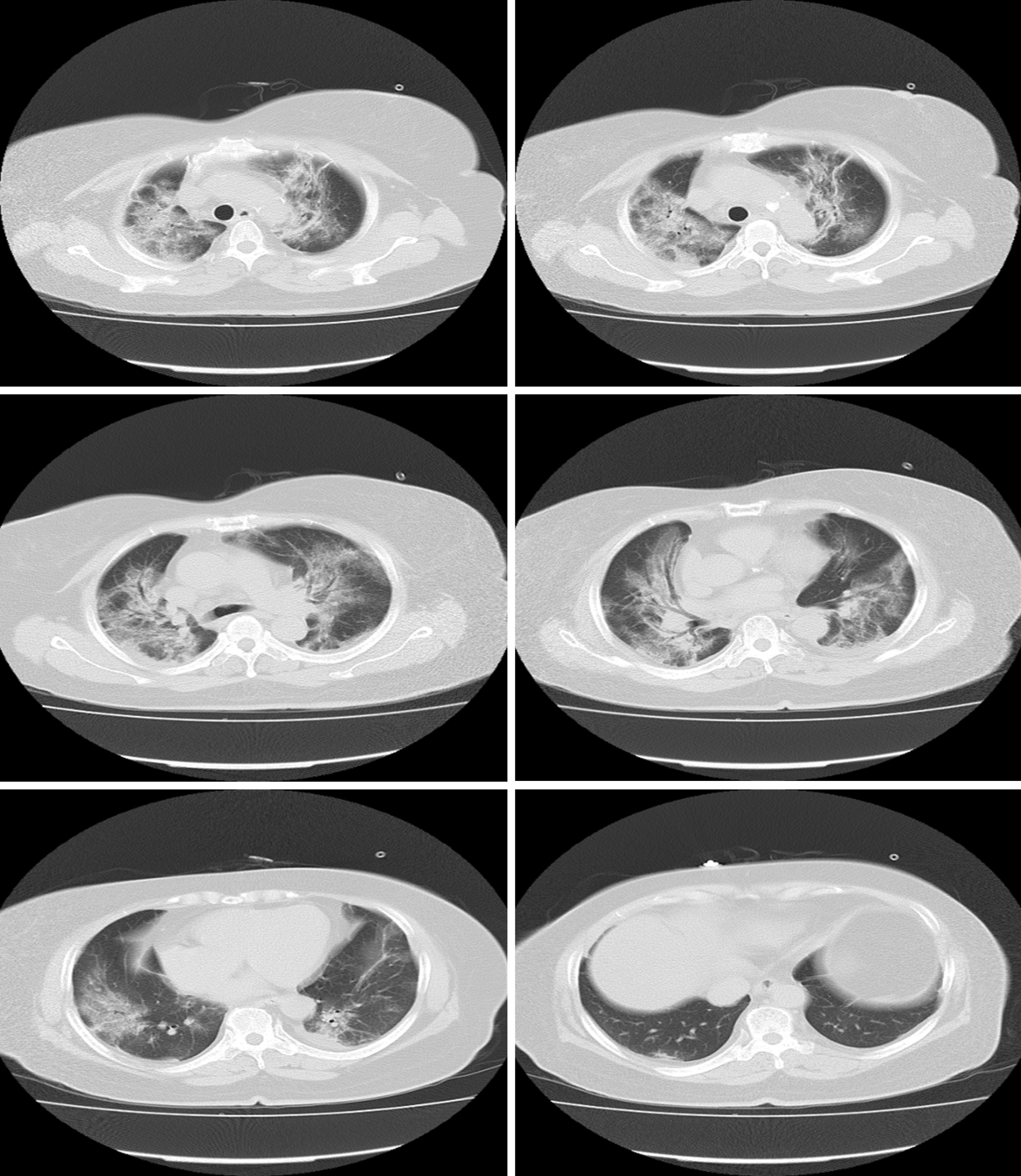

A chest CT showed bilateral ground-glass lung changes (Figure 2).

We diagnosed this patient with suspected COVID-19 based on the symptoms of fever and cough, lung changes on CT, and a normal WCC and lymphocyte percentage. After admission, a diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed with a positive 19-nCoV nasopharyngeal swab nucleic acid test. Her COVID-19 presentation was classified as a severe type because her P/F ratio was less than 300 mmHg[2].

The final diagnosis of the presented case is severe COVID-19 with respiratory failure.

The patient was given supplemental inhaled oxygen (5 L/min, FiO2 41%) and prescribed a bundle therapy including: Lopinavir/ritonavir antiviral tablets (500 mg/12 h) with α-interferon (5.0 × 106 U/12 h, atomized inhalation), thymosin (1.6 mg/d, subcutaneous injection), methylprednisolone (40 mg/d for the first 3 d), Xuebijing (100-mL injection/12 h), and low-molecular-weight heparin (4.0 kIU/d, subcutaneous injection).

Following medium-flow nasal oxygen (5 L/min, FiO2 41%) for 2 h, the patient’s condition had not improve. She complained of shortness of breath and her respiratory rate was about 26 breaths/min. Therefore, she was started on high-flow nasal cannula oxygen (HFNC) with 50 L/min of flow and a 60% FiO2. In the first 2 d after admission, the patient’s fever came down gradually and her P/F ratio was sustained in the range of 209-246 mmHg. However, during the night of the 3rd d after admission (January 28), she coughed badly without sputum, and experienced dyspnea, even on HFNC. She was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) at 00:08 on January 29. Immediately upon her admission to the ICU, she had a P/F ratio of 127 mmHg and was thus placed on non-invasive ventilation (NIV; inspired positive airway pressure 12 cmH2O, expiratory positive airway pressure, 6 cmH2O, FiO2 60%). Subsequently, we observed a gradual improvement in her P/F ratio, which reached 320 mmHg on February 4, 2020 when the patient was able to breathe effortlessly and reported feeling well.

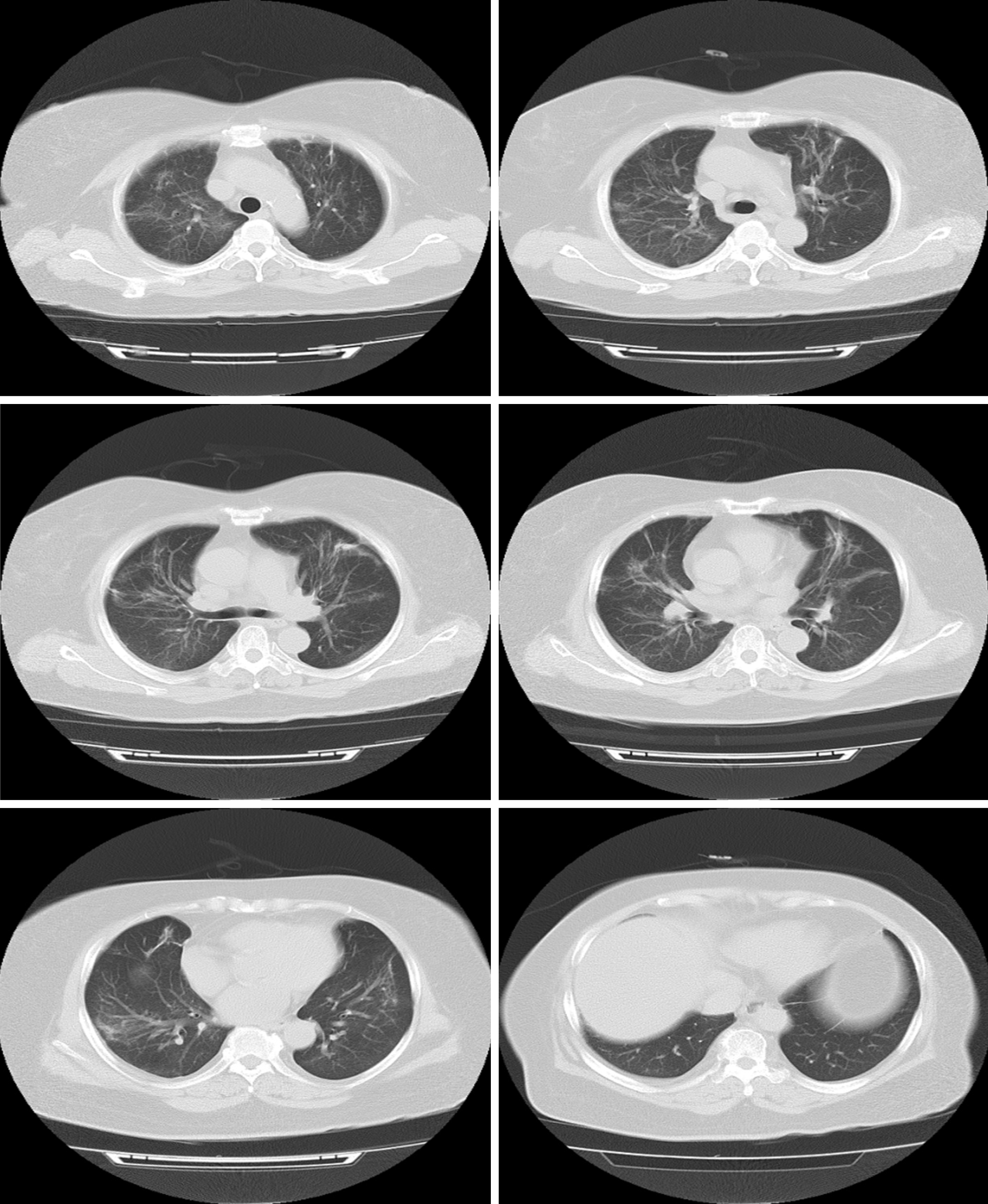

A follow-up chest CT performed on February 20, 25 d after admission, showed that the patient’s bilateral ground-glass lung changes had been mostly absorbed (Figure 3). Concurrently, the patient met the criteria for post-COVID-19 discharge: A normal body temperature for > 3 d, alleviation of respiratory symptoms, majority resolution of radiological lung changes, and two consecutive negative respiratory nucleic acid tests with a sampling interval of ≥ 1 d. She was discharged on March 3.

COVID-19 outbreaks, which started on December 12, 2019, had already caused 2794 laboratory-confirmed infections with 80 fatal cases by January 26, 2020[5]. Initially, 2019-nCoV infections spread to several provinces in China, and then to other countries, developing into a worldwide pandemic with over a million cases, and over 80 000 deaths, as of the time of the wiring of this report. In response, the Chinese government and medical institutions have mobilized substantial resources and have undertaken a variety of measures to treat patients proactively and limit the spread of the COVID-19[6]. However, curbing the spread of 2019-nCoV infections has proven to be extremely difficult given that it has been estimated to have a basic reproduction rate of 2.2 (90% confidence interval, 1.4-3.8), indicating a potential for sustained human-to-human transmission[7].

Characteristics of COVID-19 include exponential disease contagion, atypical clinical symptoms that can lead to missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis, as well as difficult detection and assessment during the early stages of infection. COVID-19 should be suspected in patients exhibiting fever, cough, myalgia, weakness, and dyspnea. Chest CT may enable early detection of COVID-19, and should be ordered in patients showing at least some of these symptoms[3,4]. In the present case, a clinical diagnosis was based on the presence of fever with a normal WCC/lymphocyte percentage and bilateral ground-glass lung changes on CT, and then confirmed with nucleic acid testing.

Early appropriate respiratory support is critical for optimizing the prognosis of patients with COVID-19. In a study of 138 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China[8], it was determined that, from the appearance of the first symptoms of infection, it may take 5 d for dyspnea to develop, and only 8 d for progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome. In a study of 36 patients with COVID-19 requiring intensive care, Wang et al[8] reported that 4 patients (11.1%) received high-flow oxygen therapy, 15 (41.7%) received NIV, and 17 (47.2%) received invasive ventilation (4 were switched to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation). They observed an overall mortality rate of 4.3%[8]. The present case highlights the importance of early detection of disease severity and appropriate selection of respiratory support for COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure. Our patient received early appropriate oxygen therapy that enabled her to overcome an oxygen deficit, allowing her organs to continue to function normally. We applied, sequentially, medium-flow nasal oxygen, HFNC, and finally NIV when the patient’s P/F ratio dropped below 200 mmHg. We determined the choice of oxygen therapy based on each patient’s respiratory condition, in particular the P/F ratio, and proceed from low to high support, starting from medium-flow nasal oxygen to HFNC and NIV under close clinical monitoring.

We advocate that NIV be initiated without hesitation when the P/F ratio drops below 200 mmHg. Safe and effective NIV requires a proficient (1 + 1):1 team [i.e., (1 doctor + 1 nurse):1 patient] adhering to the provision of strict protective clothing. If the patient’s condition does not improve and his or her P/F ratio remains persistently below 200 mmHg after 2 h of NIV, invasive mechanical ventilation should be applied immediately. For our present patient, after NIV, her respiratory and P/F ratio improved gradually. Because NIV provided enough oxygen for her, she did not require a higher level of respiratory support.

Pharmacologically, we applied a bundle therapy which included an antiviral cocktail (lopinavir/ritonavir plus α-interferon), an immunity enhancer (thymosin), a corticosteroid to reduce pulmonary exudation (methylprednisolone), a traditional Chinese medicine-derived anti-inflammatory prescription (Xuebijing), and an anti-coagulant to prevent deep vein thrombosis (heparin). No randomized controlled trials with a specific anti-coronavirus agent have been conducted with respect to COVID-19 therapy or prophylaxis. Reports using historically matched controls have suggested that treatment with α-interferon combined with a steroid and protease inhibitors could be useful[9]. The antiviral cocktail (lopinavir/ritonavir plus α-interferon) given to this patient was consistent with the national guidelines for COVID-19 treatment in China[2]. Lopinavir/ritonavir acts mainly on the replication phase of virus invasion. Lopinavir is an HIV protease inhibitor that blocks the division of the Gag-Pol polyprotein, leading to the production of immature, noninfectious viral particles. Ritonavir, an active mimicry inhibitor of HIV-1/2 aspartic protease, can inhibit HIV protease, generate immature HIV particles, and interrupt the infection cycle. Additionally, it inhibits cyp3a-mediated metabolism of lopinavir, leading to higher systemic lopinavir concentrations.

Adjuvant steroid therapy has been reported to be useful for coronavirus- infected patients[9]. However, it has been reported that large dose glucocorticoids in the early stage may disrupt patients’ metabolism and modify immunosuppression of severe acute respiratory syndrome in a manner that leaves patients at risk of a severe secondary infection[10]. Moreover, compared to patients who received lower cumulative doses over a shorter period of time, severe acute respiratory syndrome patients who received higher cumulative doses and longer treatment durations of steroids have been reported to be more likely to later develop osteonecrosis[11]. Thus, to curtail these risks, it would be prudent to reduce the risk of steroid use by minimizing steroid dose and duration of administration in COVID-19. The present patient received 40 mg/d methylprednisolone for 3 d, during an early disease progression phase characterized by dyspnea development and rapid worsening of signs of lung pathology, in accordance with the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 released by the National Health Commission of China (Trial Version 5)[2].

Injection of Xuebijing, the dominant components of which are hydroxysafflor yellow A, oxy-paeoniflorin, senkyunolide I, and benzoylpaeoniflorin[12], has been reported to lead to improved pneumonia severity, and reduced ICU stay duration, mechanical ventilation duration, and mortality in critically ill patients with severe pneumonia[13] through modulation of the production of cytokines, particularly tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6[14]. For our patient, we used Xuebijing (100-mL injection/12 h) to counter patient’s inflammatory response in accordance with the national guidelines for COVID-19 management[2].

Our patient responded well to a combination of early NIV with a bundle pharmacotherapy and had a good outcome. We recommend that this treatment plan be considered for patients with severe COVID-19.

We acknowledge the writing guidance provided by Prof. Kun-Mei Ji and the training camp for medical research held by Shenzhen Medical Association and Huada. We are grateful to the physicians and nurses at the Third People’s Hospital of Shenzhen who participated in clinical examinations and sample collection.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gajic O, Kenzaka T S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: MedE-Ma JY E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18987] [Cited by in RCA: 17648] [Article Influence: 3529.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lin L, Li TS. [Interpretation of "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infection by the National Health Commission (Trial Version 5)"]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;100:805-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhou L, Liu HG. [Early detection and disease assessment of patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43:167-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu K, Fang YY, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang MF, Ma JP, Xiao W, Wang YN, Zhong MH, Li CH, Li GC, Liu HG. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in RCA: 856] [Article Influence: 171.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15248] [Cited by in RCA: 14131] [Article Influence: 2826.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Gao ZC. [Efficient management of novel coronavirus pneumonia by efficient prevention and control in scientific manner]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43:163-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Riou J, Althaus CL. Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), December 2019 to January 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 751] [Article Influence: 150.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14113] [Cited by in RCA: 14767] [Article Influence: 2953.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wong SS, Yuen KY. The management of coronavirus infections with particular reference to SARS. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:437-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li XW, Jiang RM, Guo JZ. [Glucocorticoid in the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome patients: a preliminary report]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2003;42:378-381. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Zhao R, Wang H, Wang X, Feng F. Steroid therapy and the risk of osteonecrosis in SARS patients: a dose-response meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:1027-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zuo L, Sun Z, Hu Y, Sun Y, Xue W, Zhou L, Zhang J, Bao X, Zhu Z, Suo G, Zhang X. Rapid determination of 30 bioactive constituents in XueBiJing injection using ultra high performance liquid chromatography-high resolution hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometry coupled with principal component analysis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2017;137:220-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Song Y, Yao C, Yao Y, Han H, Zhao X, Yu K, Liu L, Xu Y, Liu Z, Zhou Q, Wang Y, Ma Z, Zheng Y, Wu D, Tang Z, Zhang M, Pan S, Chai Y, Song Y, Zhang J, Pan L, Liu Y, Yu H, Yu X, Zhang H, Wang X, Du Z, Wan X, Tang Y, Tian Y, Zhu Y, Wang H, Yan X, Liu Z, Zhang B, Zhong N, Shang H, Bai C. XueBiJing Injection Versus Placebo for Critically Ill Patients With Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e735-e743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen X, Feng Y, Shen X, Pan G, Fan G, Gao X, Han J, Zhu Y. Anti-sepsis protection of Xuebijing injection is mediated by differential regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory Th17 and T regulatory cells in a murine model of polymicrobial sepsis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;211:358-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |