Published online May 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i9.1679

Peer-review started: January 6, 2020

First decision: March 18, 2020

Revised: March 22, 2020

Accepted: April 4, 2020

Article in press: April 4, 2020

Published online: May 6, 2020

Processing time: 115 Days and 4.7 Hours

Pyoderma gangrenosum resulting from or associated with congenital preauricular fistula is rarely reported.

We report a rare case of pyoderma gangrenosum misdiagnosed as preauricular fistula infection. To our knowledge, this is the first report to describe pyoderma gangrenosum originating from the site of preauricular fistula. The lesion continued expanding even after combined treatment of systemic antibiotics and thorough debridement. Taking into account the possibility of pyoderma gangrenosum, we applied soft care with normal saline and Vaseline gauze dressing. Systemic corticosteroids were not used until intestinal Clostridium difficile was controlled. No local recurrence was noted at the 12-mo follow-up.

This case highlights the necessity of considering rare diseases, such as pyoderma gangrenosum, when the preauricular sinus deteriorates with general management. The treatment strategy is mutually conflicting between pyoderma gangrenosum and infection of the preauricular sinus.

Core tip: Acute infection of the preauricular sinus is common in clinical practice, while pyoderma gangrenosum is rare. We here report a rare case of pyoderma gangrenosum that was initially treated as common preauricular sinus infection and did not respond to traditional management. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a noninfectious inflammatory dermatosis that presents as an inflammatory disorder of the skin. The most common comorbidity is inflammatory bowel disease. Diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum should be considered when standard management is not effective or it is complicated with inflammatory bowel diseases.

- Citation: Zhao Y, Fang RY, Feng GD, Cui TT, Gao ZQ. Pyoderma gangrenosum confused with congenital preauricular fistula infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(9): 1679-1684

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i9/1679.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i9.1679

Congenital preauricular sinuses are commonly encountered by otolaryngologists. The incidence of preauricular sinuses varies from 0.23% to 1.91%, with a higher prevalence in the Asian population[1]. They usually present as asymptomatic small pits adjacent to the anterior margin of the helix. Preauricular sinuses may extend superior or posterior to the auricle. Preauricular sinuses can be either inherited or sporadic, and bilateral sinuses tend to be inherited[2]. Preauricular sinuses are sometimes a part of other conditions or syndromes in 3%-10% of cases, primarily associated with deafness and branchio-oto-renal syndrome[2]. In cases of recurrent local infection, radical cure is achieved only through complete excision of the sinus. However, total extirpation is difficult in the presence of acute infection. In the acute stage, systemic antibiotics and drainage are first-line treatments. However, we present a rare case of preauricular sinus infection that did not respond to traditional management.

A 26-year-old female patient presented to our emergency room complaining of swelling and pain in the left preauricular region over the past four weeks.

She was febrile to 39 °C and had diarrhea up to more than ten times/d. Her local otolaryngologist prescribed her intravenous antibiotics, including piperacillin, sulbactam, and metronidazole. Symptoms were not relieved. One week later, incision and drainage were applied in the preauricular region. However, her general status continued to deteriorate, and the wound began to spread to peripheral tissues.

The patient was found to have bilateral preauricular sinuses after birth. She had a history of Crohn’s disease over one year, which was otherwise controlled well with mesalazine and fecal microbiota transplantation.

Physical examination demonstrated a large ulcer before and above the left auricle and a preauricular fistula on the right side; no facial palsy was found (Figure 1). The anterior wall of the external auditory wall was red and swollen, and no perforation of the tympanic membrane was observed.

A full blood count was abnormal, with increased white blood cells of 15.56 × 109/L, predominantly neutrophils. Serum albumin decreased to 31 g/L, and serum potassium was 2.5 mmol/L. Antibody spectrum detection included immunofluorescence anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (IF-ANCA) (+) P1:10, ANCA-IgA (+) C1:10; the rest were negative. The bacterial culture of local drainage fluid was negative.

A head CT (Figure 2) scan revealed skin and subdermal soft-tissue defects without obvious erosion into the facial muscle and parotid gland.

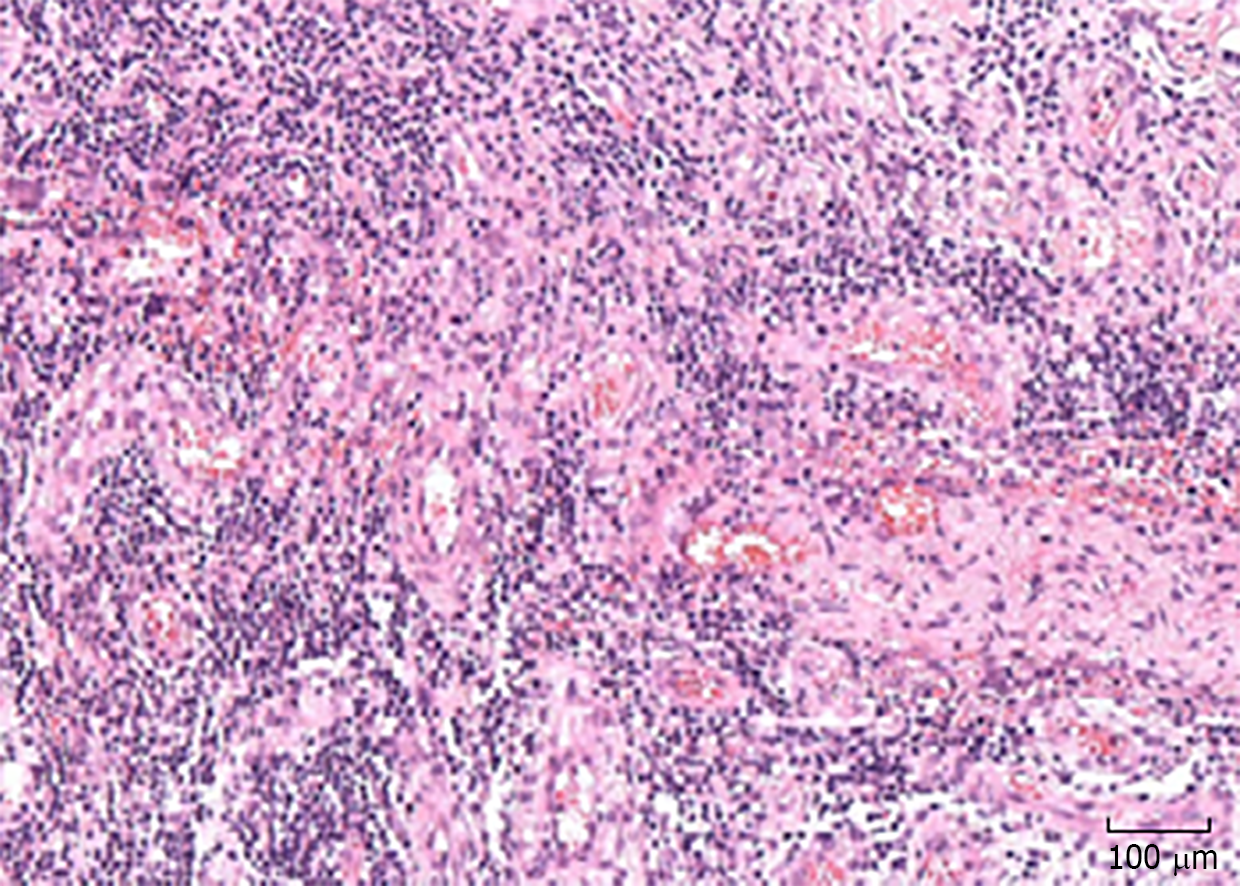

Considering that the first incision and drainage might not be radical, a thorough debridement was performed after informed consent was obtained from the patient. Intraoperatively, nearly all suspected lesion tissues were removed until the margin of fresh tissue. However, the lesion area did not stop expanding after the second debridement. General status and diarrhea were even worse. Removed tissues were sent to undergo bacterial, fungal, and TB culture, which were all negative. Biopsy revealed (Figure 3) inflammation of the mucosa with infiltration of inflammatory cells. Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) was identified from feces. Colonoscopy revealed diffuse inflammation and ulcers in the transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. Biopsy of sigmoid colon revealed diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells and structural disturbance of intestinal crypts.

The patient is suspected of having pyoderma gangrenosum due to the local sign around the ear area. A biopsy and thorough pathologic test are needed. Before that, radical debridement should be avoided.

Although the patient was suspicious of Crohn’s disease before, no definite evidence is available at present. The diagnosis of Crohn’s disease is not established, but highly suspicious. Further examination including repeated colonoscopy and abdominal CT scan should be performed. Since C. difficile is positive, glucocorticoids should be prescribed with care.

Bacterial infection cannot explain the whole process of disease. Noninfectious diseases such as pyoderma gangrenosum are highly suspected. To prevent infection, intravenous cefmetazole sodium is suggested.

The final diagnosis of the presented case is pyoderma gangrenosum with inflam-matory bowel disease.

Local care changed from thorough debridement to moisture keeping. Any irritating solution, including iodophor, was avoided. Since C. difficile was identified from feces, systemic corticosteroids were contraindicated. She was prescribed intravenous immunoglobulin 30 g qd for 3 d. Besides, cefmetazole sodium 1 g bid, minocycline 100 mg bid, sulfasalazine 1 g qid, and enteral vancomycin 125 mg qid was administered. To relieve diarrhea, she changed her diet to enteral nutritional powder tid. She was also prescribed combined Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and Enterococcus capsules tid for at least 3 mo. One day later, the wound stopped expanding. Six days later, fresh tissue was observed in the preauricular area. Diarrhea gradually stopped in two weeks. Cefmetazole and vancomycin were discontinued after two weeks, and the patient continued taking minocycline and sulfasalazine for 2 mo.

The wound began to contract until a persistent ulcer remained in the center for several months. Three mo later, systemic corticosteroids were prescribed after a fecal culture was performed again, and no C. difficile infection was found. The renal and hepatic function test results were generally within normal range. The colonoscopy performed 5 mo later found diffuse hyperemia and interspersed polyps in the transverse colon, descending colon and sigmoid colon. The wound completely recovered with a scar after 6 mo (Figure 4). She did not show signs of relapse after an 18-mo follow-up. Her life gradually went back to normal.

Acute infection of the preauricular sinus mainly manifests as a localized abscess or facial cellulitis[3]. Treatment in the acute stage involves systemic antibiotic therapy and, at times, incision and drainage. Almost all patient symptoms are resolved after drainage. Nevertheless, in this case, the response following drainage was contrary to previous experience, which led us to doubt the primary diagnosis and consider some rare diseases.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare noninfectious inflammatory dermatosis that presents as an inflammatory and ulcerative disorder of the skin. There are several subtypes, with the classic ulcerative type being the most common (approximately 85%)[4]. It is often misdiagnosed due to its rareness and undefined diagnostic criteria, especially for surgeons such as otolaryngologists. PG is more common in females than in males (with a ratio of 3:1), with a mean age of 51 years at presentation[5]. It is a disorder belonging to neutrophilic diseases, whereas the precise pathogenesis is unknown. Abnormalities of cytokines, chemokines, and neutrophils combined with specific genetic mutations might lead to neutrophilic recruitment and activation[6].

The diagnosis of PG is frequently established by clinical features and exclusion of other similar diseases. Su et al[7] proposed diagnostic criteria for classic ulcerative PG, in which rapid progression of a necrolytic cutaneous ulcer and exclusion of other causes were listed as major criteria. It is required that diagnosis should be established based on both major criteria and at least two minor criteria. However, a diagnosis of exclusion is impractical and hard to manipulate. In this case, biopsy and subsequent response to treatment excluded lymphoma; repetitive smears and reaction to antibiotics did not support infection; biopsy result and low titer of ANCA was not typical for granulomatosis with polyangiitis. More recently, a new diagnostic criterion based on a Delphi consensus of international experts was proposed, requiring one major criterion and eight minor criteria. The major criterion was biopsy of the ulcer edge, demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate[8]. In this case, the major criterion and five minor criteria were met. However, the difficulty in diagnosis lies mainly in an awareness of the disease. Two uncommon clinical features guided us to consider and confirm the diagnosis: (1) No relief after thorough debridement; and (2) Complicated with inflammatory bowel disease. It has been reported that associated medical comorbidities are seen in approximately 67% of patients, with inflammatory bowel disease being the most common[5,9].

Theoretically, any area of the body can be affected by PG. Sites of involvement mainly include the trunk, lower extremities, upper extremities, and head and neck[10]. The head and neck are sometimes affected by PG, but only a few cases involving the auricular area have been reported to date. Dos Santos Sousa et al[11] summarized the reported cases of PG involving the auricular area. Nearly 30% of the cases were associated with inflammatory bowel diseases. However, none of them were reported to be associated with the preauricular sinus, and it seemed that the appearance of local PG was not a predictor of systemic diseases.

It was a confounding factor that the preauricular sinus and initial pustule occurred at this site in this case. Realizing the possibility of PG, we changed radical debridement to soft care with normal saline and Vaseline gauze dressing. Lesions of PG often start in healthy skin and may be provoked by a trauma. Pathergy is the term used to refer to hyperreactivity to minimal trauma, and PG can exhibit clinical pathergy[12]. There is no gold standard for the management of PG. Treatment includes local and systemic management. Topical gentle care with sterile saline and dressing promoting moisture, with or without corticosteroids, are often tried initially. Debridement of PG may result in an exponential increase in lesion size and deterioration. In addition, because of the pathergy in PG, skin grafts should be considered with caution. For severe cases, systemic treatment, such as systemic corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive medications, such as cyclosporine, are first-line choices[13]. However, C. difficile was identified from feces, and systemic corticosteroids were contraindicated. The sign of recovery was evident within one week after the shift of treatment, but subsequent healing took several months.

Preauricular sinus infection is a common clinical condition, while pyoderma gangrenosum is rare. Pyoderma gangrenosum should be considered when standard management is not effective or it is complicated with inflammatory bowel diseases. Generally, corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, while radical incision and drainage should be avoided.

We thank Rou-Yu Fang, MD (Department of Dermatology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China), Ya-Min Lai (Department of Gastroenterology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China) and Yun-Lu Feng (Department of Gastroenterology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China) for their help in reading the histopathological results and assistance in diagnosis. We also thank the patient for granting permission to publish this report.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Marcos M, García-Elorriaga G S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: MedE-Ma JY E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Lee KY, Woo SY, Kim SW, Yang JE, Cho YS. The prevalence of preauricular sinus and associated factors in a nationwide population-based survey of South Korea. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35:1835-1838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Scheinfeld NS, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, Nozad V. The preauricular sinus: a review of its clinical presentation, treatment, and associations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:191-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rataiczak H, Lavin J, Levy M, Bedwell J, Preciado D, Reilly BK. Association of Recurrence of Infected Congenital Preauricular Cysts Following Incision and Drainage vs Fine-Needle Aspiration or Antibiotic Treatment: A Retrospective Review of Treatment Options. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143:131-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum - a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19:224-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ashchyan HJ, Butler DC, Nelson CA, Noe MH, Tsiaras WG, Lockwood SJ, James WD, Micheletti RG, Rosenbach M, Mostaghimi A. The Association of Age With Clinical Presentation and Comorbidities of Pyoderma Gangrenosum. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:409-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:691-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:790-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, Fiorentino D, Callen JP, Wollina U, Marzano AV, Wallach D, Kim K, Schadt C, Ormerod A, Fung MA, Steel A, Patel F, Qin R, Craig F, Williams HC, Powell F, Merleev A, Cheng MY. Diagnostic Criteria of Ulcerative Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Delphi Consensus of International Experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shahid S, Myszor M, De Silva A. Pyoderma gangrenosum as a first presentation of inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schoch JJ, Tolkachjov SN, Cappel JA, Gibson LE, Davis DM. Pediatric Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Retrospective Review of Clinical Features, Etiologic Associations, and Treatment. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dos Santos Sousa MC, Lima Lemos EF, Oliveira De Morais O, Silva Leite Coutinho AS, Martins Gomes C. Pyoderma gangrenosum leading to bilateral involvement of ears. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:41-43. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Varol A, Seifert O, Anderson CD. The skin pathergy test: innately useful? Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:155-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Alavi A, French LE, Davis MD, Brassard A, Kirsner RS. Pyoderma Gangrenosum: An Update on Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:355-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |